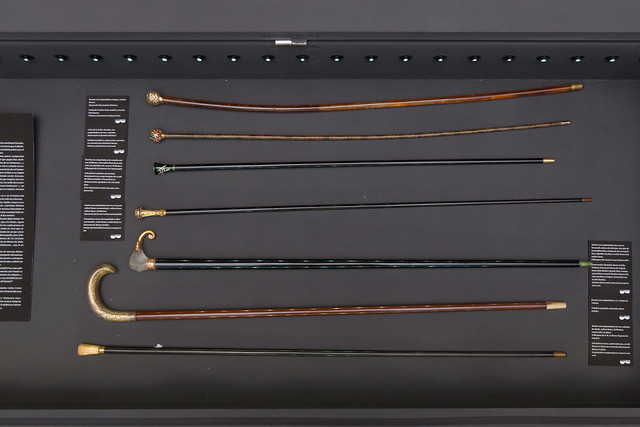

An example of men's jewellery: violinist Pablo Sarasate's cane grips.

PAMPLONA CITY COUNCIL COLLECTION

IGNACIO MIGUÉLIZ VALCARLOS

Throughout history, jewellery has undergone a constant evolution, changing according to the events and tastes of the moment, adapting to different styles and fashions. In general, it has been women's jewellery that has set the tone for these transformations and has been the focus of researchers' interest, although men's jewellery has also undergone the same process. This evolution will be shown in a dizzying way throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, as the changes experienced by society due to the French Revolution and the Industrial Revolution, will cause a substantial alteration in social hierarchies and in the role of men, which will also be reflected in the way they dress. More practical fashions were to be adopted, allowing them greater freedom of movement, more in keeping with the activities of modern man. This also led to the renewal of their jewellery. Thus, military orders, bows and orders of command, ribbons and ties, buckles and chains, sword hilts, etc., which were the main items of jewellery for men throughout the Ancien Régime, gave way to more fashionable jewellery, such as watches and fob watches, cufflinks, buttons, tie clips and baton grips.

The walking stick was a very important masculine accessory, used since antiquity, where it was employeein a utilitarian way as a support for walking and as a defensive weapon, going on to become an element of power as a baton of command, with a symbolism linked to the authority and power of the bearer. During the Modern Age this piece maintained its relationship with power, being used as a baton of command by civilians and soldiers, as well as appearing as a sign of distinction in the privileged classes, which is why it was common to include this accessory in male portraits together with the sword. It was not until the twentieth century that the use of the latter was relegated to men's clothing, while the cane became more important as an indispensable accessory for the gentleman, especially during the Belle Époque, since, in addition to being used for support, it enhanced the elegance and refinement of the person who carried it. But the peculiarity of these canes was centred on their handles, which ranged from the most modest, carved from the same wood as the cane, to the richest, made from expensive materials, and sometimes in whimsical shapes, which led some of them to be described as extravagant.

Within the walking sticks we can appreciate different models depending on their handles, such as the arched one, which has the classic curved finish on the upper part, which has been widely used throughout history. Another would be the so-called Milord, which was very common in England in the 18th and 19th centuries, spreading its use throughout the rest of the world. It has a cylindrical top, with a warped or mixtilinear profile, also playing with the top, which can be flat or incorporate a decorative element. There is also the subjectpomo, in which the upper end is a spherical body in the form of a knob, to which a ferrule may or may not be added, a body that joins the handle to the shank, which can adopt different shapes, generally enhancing the sphere that forms the handle.

Recognised and admired worldwide, the Navarrese violinist Pablo Sarasate was one of the most distinguished figures of music in Spain at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. He was born in Pamplona, where he received his first degree training, and continued his studies in Santiago de Compostela and Pontevedra, at which point he obtained a scholarshipto study in Madrid and later another from Queen Isabella II in 1856 to continue his studies trainingin Paris. The year after his arrival in the French capital, he obtained the first awardfrom the violin conservatory, which opened the doors of all the European and American concert halls, and marked the beginning of a brilliant degree programas a concert performer.

Throughout his career he received gifts from numerous admirers, including not only royalty, such as the queens of Spain and England and the Empress of Germany, and aristocracy, such as Princess Metternich, Baron Rothschild and General Schouvaloff, but also from governments around the world and anonymous personalities. Many of these gifts were in the form of jewellery, including rings, tie-pins, buttons, cufflinks, watches, cigarette cases and walking sticks, most of which were bequeathed by the artist, along with other pieces, to Pamplona City Council for display in the museum that the Pamplona Regiment planned to dedicate to his illustrious countryman. However, despite possessing all this jewellery, Sarasate was a man of great austerity and did not usually make use of them, except for his walking sticks, and the musician always carried several of these works in his luggage in a portable baton case, which is why his admirers soon began to present him with this subjectof works. "They found out how fond he was of good walking sticks, and they all gave them to him in abundance issueand of excellent quality. In this way Sarasate soon found himself with a very valuable and artistic collection of walking sticks, which is famous in Spain and abroad. It is the gift he accepted most willingly and used the most. His invaluable collection included walking sticks of all kinds and from all countries". In this way, he assembled a varied collection, part of which, twelve walking sticks, considered to be the richest works he owned, he donated to Pamplona City Council between 1905 and 1906. Pieces with rich grips made of noble metals and precious stones, some anonymous and others made by the main European and American jewellers of the time: Fabergé, Cartier and Tiffany, as well as the Spanish companies Marzo and Ansorena.

- ALTADILL, J., Memoirs of Sarasate, Pamplona, 1909.

- ARBETETA MIRA, L., Ansorena. 150 years of jewellery, Madrid, 1995.

- ARBETETA MIRA, L., La joyería española de Felipe II a Alfonso XIII, Madrid, 2000.

- BARI, H., CARDONA, C., and PARODI, G.C.,Diamanti. Arte, Storia, Scienza, Rome, 2002.

- Blanco y Negro, Madrid, 10 November 1918.

- BRAITHWAITE, R., Across the Moscow river: The world turned upside down, Boston, 2002.

- CHENOUNE, F., A history of men's fashion, Paris, 1993.

- Dictionary of the Spanish language. Real Academia Española, T. I, Madrid, 2001.

- HARRISON, S., DUCAMP, E., and FALINO, J., Artistic luxury. Fabergé. Tiffany. Lalique, Cleveland, 2008.

- HILL, G., Fabergé and the Russian Master Goldsmiths, New York, 2008.

- La Vanguardia, Barcelona, 19 September 1896.

- LAVIN, J.D., Art and tradition of the Zuloagas. Spanish damascene from the Khalili collection, Bilbao, 1997.

- MAIER, J., Real Academia de la Historia. Catalog del Gabinete de Antigüedades. Antiquities XVI-XX century, Madrid, 2005.

- MARTÍN VAQUERO, R., El Patrimonio de la Diputación Foral de Álava. La Platería, Vitoria, 1999.

- MIGUÉLIZ VALCARLOS, I., "Un ejemplo de joyería masculina: empuñaduras de bastón del violinista Pablo Sarasate", in programs of study de Platería. San Eloy 2013, Murcia, 2013.

- MIGUÉLIZ VALCARLOS, I., "Joyería masculina europea: Alhajas del violinista Pablo Sarasate", in Herradón Figueroa, M.A. (Coord.), conference proceedingsde II congressEuropeo de Joyería. Vestir las joyas. Modas y Modelos, Madrid , 2015.

- NADELHOFFER, H., Cartier, San Francisco, 2007.

- NIGAM, M.L., Bijoux indiens, Paris, 1999.

- PHILLIPS, C. (Ed.), Bejewelled by Tiffany (1837-1987), London, 2007.

- PURCELL, K., Falize. A dynasty of jewelers, London, 1999.

- SAN MARTÍN, J., LARRAÑAGA, R., and CELAYA, P.,El damasquinado de Eibar, Eibar, 1981.

- SILVEIRA GODINHO, I., Tesouros reais, Lisbon, 1992.

- VASSALLO E SILVA, N., and CARVALHO DIAS, J., Cartier 1899-1949. The evolution of a style, Lisbon, 2007.

- VON HABSBURG, G., Fabergé imperial craftsman and his world, London, 2000.

- VON HABSBURG, G., Fabergé revealed at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, 2011.

- VON SOLODKOFF, A., Masterpieces from the House of Fabergé, New York, 1984.