Navarrese Law in its fundamental texts

MERCEDES GALÁN LORDA

The regional law

One of the constituent elements of Navarre's identity is precisely its law, expressed and represented, at the same time, in the term regional law.

It is not in vain that Navarre is the only one of the seventeen Spanish Autonomous Communities to bear the designation of "Foral". This designation, that of Comunidad Foral, expresses that Navarre has maintained its own law or legal system uninterruptedly throughout time and right up to the present day. That is to say, there has never been a moment in history when this right or legal system has been suspended in its entirety, although it has been considerably reduced with the passing of time.

reference letter The expression used over the years to refer to a right of one's own has been the term regional law.

It should be clarified that the word regional law is in general use and refers to the particular legal regime enjoyed by certain places or persons with a certain status. It is common, for example, to hear the expression aforados referred to people who, because they hold a public position , enjoy a special legal regime.

The word regional law derives from the Latin expression forum, which was related to the exercise of a court's jurisdiction and which, at final, was extended to the application of a certain rules and regulations.

Throughout the Age of average, the expression regional law was in general use to refer to the legal status of a place or of a group of people. In this way, all localities had their regional law or legal system, i.e. their own law. For this reason, when studying medieval law, it is necessary to refer to the local charters reference letter .

In the case of the Iberian Peninsula, there was an important factor to take into account, which did not occur in other parts of Europe: the Reconquest. The disappearance of the Visigothic kingdom and the emergence of the new political centres that were formed as it progressed, determined the emergence of a new law, of course inspired by traditional law, already known and practised, but also with its own elements, differential to each place or human group .

One of the three political nuclei that emerged on the Iberian Peninsula after the Reconquest, together with the kingdom of Asturias and the Catalan counties, was precisely the kingdom of Pamplona. For this reason, it is possible to refer to reference letter as Navarre's own right from the moment it was constituted as a distinct political entity, first called the Kingdom of Pamplona and, from 1162, the Kingdom of Navarre.

Since its emergence as a kingdom, Navarre has gone through four stages in its constitutional history, in the sense that its political structure or status has changed over time.

These four stages are as follows:

-

Navarre, independent kingdom (905-1512)

-

Navarre, a separate kingdom within the Crown of Castile (1515-1841)

-

Navarre, from kingdom to province (1841-1978)

-

Navarra, Comunidad Foral ( 1978-present)

The following is a brief reference letter of the most representative texts of Navarrese law in each of the stages mentioned.

The first king known to knowledge to use the degree scroll de rex was Sancho Garcés, who in 905 called himself rex Pampilonensis, which is considered to be the year in which the kingdom was established.

Navarre, as an independent kingdom, had its own monarchy, its own institutions and its own law.

Law, as a set of rules that ordered social coexistence, was at first and throughout the High Ages average, preferably local. This means that each place had its own legal system, with its own rules. This fact is explained by the fact that this was a long period of time in which the kingdom was in a phase of creation and its territorial limits were changing. There were times of extensive expansion, as in the reign of Sancho III the Great, and others of considerable reduction of the territory to which the royal power extended.

In any case, this was an extensive period of construction and settlement of the kingdom of Navarre. Since not only were the territorial limits not fixed, but also, for fifty-eight years, the King of Aragon held the kingdom of Pamplona (from the death of Sancho IV in Peñalén in 1076 until that of Alfonso the Battler in 1134), two realities can be explained: on the one hand, the gradual granting of charters to different localities; and, on the other, the great influence of the Aragonese charters in Navarre.

As the consolidation of the kingdom progressed, different towns in Navarre were granted charters. It can be said that each locality had its own regional law, which set out the legal system or rules governing its population.

However, as is logical, many of these charters have a similar content. It was common for the regional law of one locality to be extended to others, either because the inhabitants requested it or because the king himself extended the system from one locality to others. This explains why the fueros can be grouped into families. A family of charters is a set of charters or legal systems that are similar because they come from a common origin, i.e. they have followed the same model, a regional law which is considered to be the head of the family.

During the long period of time in which Navarre was an independent kingdom, each locality enjoyed its own regional law. These fueros, which constituted what is known as local law, have traditionally been grouped into seven families: those of the fueros of Estella, Jaca-Pamplona, Sobrarbe (Tudela), Viguera-Val de Funes, Novenera, Daroca and Medinaceli. Thus, these are the seven most representative texts of local law in Navarre in the Middle Ages average. As the regional law of Daroca is an Aragonese text and that of Medinaceli Spanish, there are five families of Navarrese fueros.

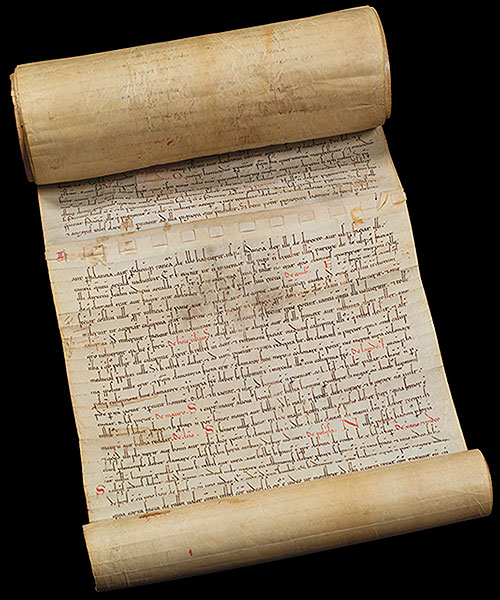

regional law of Estella confirmed by Sancho VI the Wise. file Historical Municipal Archives of Estella-Lizarra, perg. no. 1.

Granted to Estella in 1090 by Sancho Ramírez, King of Aragon and Navarre, such an important population of Franks settled in the town that this king is considered to be the founder of the city.

This regional law is inspired by that of Jaca, so that it is in fact part of its family. From the regional law of Jaca are taken the acquisition of property by possession of year and day (usucapion), the limitation of the judicial duel as a means of test, the fact that no one could be detained if they provided suitable guarantors, and other procedural guarantees.

On the basis of Jaques law, a local judicial internship developed in Estella, as well as its own custom, which led to the regional law being extended, and a text was drawn up in Estella that was approved by Sancho the Wise in 1164.

The regional law de Estella was edited by Lacarrra and Martín-Duque in 1969. The text of the edition is divided into three parts. The first 14 chapters or laws, which are preceded by a preamble in which the king grants the regional law to the settlers of Estella, make up what is considered to be the oldest part. It is thought that this first part may have been the regional law granted by Sancho Ramírez in 1090. Its contents include a series of privileges, whose purpose was undoubtedly to attract settlers: the estates acquired by the inhabitants of Estella were declared free of charges, property could be acquired by possession of year and day, the consent of the king and the neighbours was required to settle in Estella, and the inhabitants of Estella had to be judged in Estella and in accordance with its regional law.

The second part is a set of 70 chapters that would have been written between 1090 and 1164. It deals with civil matters, such as the acquisition of neighbourhood, censuses, the loan, usufruct, pledge and bail, donations, purchases and sales, dowry, the right of children from previous marriages, truncation or the fact that goods remain in the family branch from which they come, and inheritance matters. Also appearing are Criminal Law (theft, robbery, robbery, forces on property, damages, offences and insults, homicide or false testimony), Procedural Law (oaths, witnesses, pledge and bail as forms of guarantee in the process or various officers of the administration of justice), and some questions of an administrative nature.

The text reference letter refers to the Jewish population when dealing with the debts between Christians and Jews, and also contemplates the lawsuits between Franks and Navarrese caused by the problems of coexistence that arose between the two population groups. Something typically Estellan, which is still practised today, is to mark Thursdays as market days.

The final part of the text is made up of two confirmatory clauses, followed by the signum regis of King Sancho the Wise.

There was a reform project in the 13th century, but it was not C. Despite this, other provisions partially modified the content of the regional law, such as the exemption that Theobald II granted to the Franks to pay the collective compensation paid to the king for accidental deaths ("casual homicides"), or the fact that the consent of the local authorities (provost, mayor and jurors, a modification introduced in 1269) was sufficient for settlement in Estella.

The regional law stabilised in its 1164 version, which was the one that spread to other towns. The regional law of Estella was granted to San Sebastián (1180) and spread along the coast of Gipuzkoa. It was also granted to Artajona, Monreal, Huarte-Araquil, Olite, Puente la Reina, Tafalla, Tiebas, Torralba, Urroz and Mendigorría.

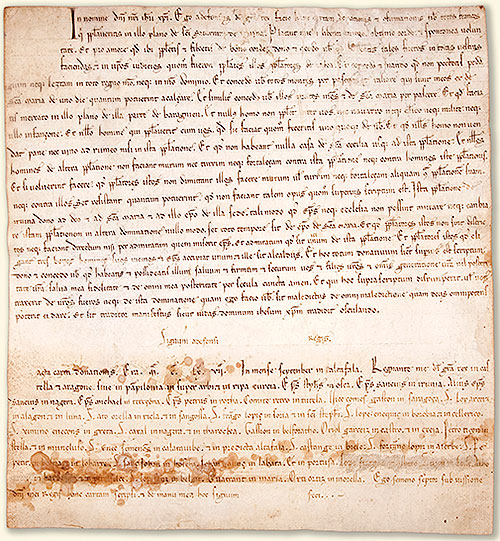

Alfonso the Battler grants the regional law of Jaca to San Saturnino de Pamplona. AGN, COMPTOS, Documents, box 1, no. 19.

The regional law of Jaca also extended to the burgh of San Saturnino in Pamplona. It was granted by King Alfonso I the Battler in 1129.

At that time Pamplona was divided into burghs. The first to emerge was the burgh of La Navarrería, made up of the neighbours who grouped around the cathedral and which was established on what was the city's first urban nucleus.

Pamplona was an episcopal dominion from the beginning of the 11th century (around 1027) until the beginning of the 14th century (in 1319 the Church renounced temporal power), although the king also enjoyed jurisdiction over the market and the portage.

In 1100, a second burgh, that of San Saturnino, a burgh exclusively of Franks, was already differentiated and was the first to receive the regional law de Jaca in 1129. The text of the concession is preserved at file Municipal de Pamplona.

According to the contents of regional law, the Franks of San Saturnino could enjoy pasture and firewood in the mountains of the King and of Santa María de Pamplona as far as they could reach in a day; they acquired the neighbourhood after a year and a day had passed; in the same deadline they could acquire property by continued possession; they could not be arrested if they presented suitable guarantors; they had to be judged in their town, by their mayor and according to their regional law; they had their own market; they were granted a monopoly on the sale of bread and wine to pilgrims; and they elected three "good men" from among them, one of whom was chosen by the bishop as mayor, responsible for dispensing justice and who, together with the twelve jurors, held the municipal representation. In addition, the bishop also chose the admiral from among the neighbours, through whom he exercised his authority.

The most extensive essay of the regional law has 338 chapters and contains the practiced law. reference letter It covers social-political matters (prerogatives of the king, obligations towards him, proofs of infantibility or the conditions of knight, villain, Jew and Moor), family matters (marriage, dowry, regime of conquests, filiation, children's rights), to other areas of the Civil Law (donations, sales and purchases, gifts, easements, leases, loans, wills), administrative matters (forests, felling, pastures, water), of Criminal Law (homicides, forces, robberies, thefts, falsehoods) and of Procedural Law (judges, lawyers, witnesses, means of test). In other words, although it is a basic regulation in many aspects, it is a complete legal regime.

Sancho the Wise ( 1161) and Theobald I (1237) confirmed the regional law .

A third burgh appeared around the parish of Saint Nicholas in the 12th century (1174-1177), which was home to Navarrese and Franks. In the same 12th century, this new burgh also came to enjoy the right of Jacobean rule. From 1189, this same right was extended to Navarre, with the exception of certain privileges.

Despite being governed by the same law, the three burghs were separated by their own walls and relations between them were often conflictive.

From 1213, there was a fourth burgh, San Miguel, attached to the Navarrería, which disappeared in 1276 with the destruction of the latter.

It was a tradition in Pamplona to go to Jaca on appeal or at enquiry. Although Sancho the Strong for bade it, in the 14th century this practice was resumed internship.

Finally, the city was unified by virtue of the Privilege of the Union of 8 September 1423. The walls of the burghs disappeared and the city came to have the same authorities.

This unification meant the end of the validity of the regional law of Jaca in the city, as Charles III the Noble decreed that from now on the regional law General of Navarre would be applied.

The Jaca-Pamplona regional law was extended to Rocaforte, Sangüesa, Larrasoaña, Villava, Villafranca, Lanz, Burguete, Lumbier, Etxarri-Aranaz, Santesteban and Urroz.

Lacarra and Martín Duque edited the text of the Jaca-Pamplona regional law in 1975.

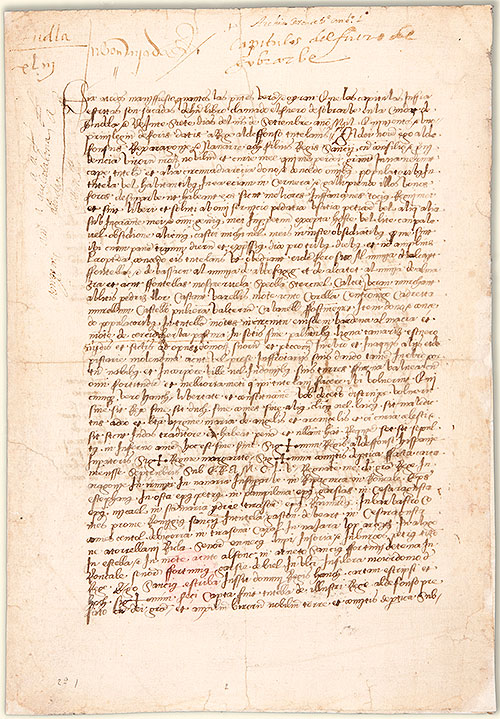

Alfonso the Battler grants the regional law of Sobrarbe to the settlers of Tudela, Cervera and Gallipienzo. AGN, COMPTOS, Documents, box 1, no. 15-2.

Although there are remains of human settlements from the Lower Palaeolithic period, Tudela was refounded by the Muladis, and at the beginning of the 12th century it was a consolidated locality that obtained the status of town in 1390. degree scroll .

Reconquered by Alfonso I the Battler in 1119, it received its town charter in 1124. It is considered to have obtained an initial privilege that granted freedom to its inhabitants and limited their military obligations to three days. According to the text of the Town Charter of 1124, the king granted the privileges of Sobrarbe to the inhabitants of Tudela, Cervera and Gallipienzo. However, it is believed that the text was adulterated by the council after 1234, when Theobald I came to the Navarrese throne, in order to recognise the privileges of the nobility implicit in the allusion to Sobrarbe.

A second privilege granted by Alfonso the Battler in 1127, known as the tortum per tortum, defined the municipal boundaries and the communal uses.

grade One of the distinguishing features of Tudela was the significant presence of the Muslim and Jewish population alongside the other bourgeoisie and infanzones who populated the town. In fact, the capitulation pact between King Alfonso and the Moorish population has been preserved, by virtue of which the Moors maintained their own jurisdiction and properties in exchange for the payment of a tithe, although they were granted deadline for a year to settle in the outskirts. On the other hand, the king tried to retain and increase the Jewish population, while also respecting their own jurisdiction.

On the basis of the privileges granted in the 12th century, Tudela developed its own law, which was written down in the 13th century, mainly on the basis of the judicial internship . Some authors consider that there was a School of Law in Tudela that could have drawn up the extensive text of the regional law based on local custom and jurisprudence, as well as on texts from neighbouring regions, preferably Aragonese.

Three medieval manuscripts of this regional law have survived (two in Madrid and the third in Copenhagen) and three different versions can be distinguished.

As was usual in the texts of the time, all branches of law are dealt with. There are political questions related to the king, such as the uprising or primogeniture in the succession to the throne, no doubt inspired by the regional law General, but also the rights of the nobles, questions of succession, procedural (forms of guarantee, means of test), criminal and civil matters.

On the one hand, the clear influence of the Roman Law and, on the other, the detailed regulations on Moors and Jews, which undoubtedly reflect the considerable presence of these two population groups in the town, stand out.

In the 14th century (around 1330), the Ordinances of the Council modified the regional law by determining that the position of judge would be for life, that eight jurors would be appointed annually from among the wisest neighbours, and that these jurors would have sixteen councillors. The penalty for murder was also modified.

The localities of Corella, Cintruénigo, Araciel, Monteagudo, Cascante, Pedriz, Tulebras, Urzante, Murchante, Calchetas, Bariellas, Buñuel, Ribaforada, Cortes, Fustiñana, Cabanillas, Murillo, Valtierra and Gallipienzo belong to the family of the regional law de Tudela, as the text was extended to them.

Alfonso I grants the regional law of Calahorra to Funes, Marcilla and Peñalén. AGN, COMPTOS, Documents, box 1, no. 5.

In 1110, Alfonso the Battler granted Funes, Marcilla and Peñalén the privileges of Calahorra and, apparently, Funes became the judicial centre of the area.

It was a border area, with the valley of Funes forming the confluence of the rivers Arga and Aragón. The main towns were Funes, Marcilla, Peñalén or Villanueva (now disappeared), Arlas (also depopulated) and Peralta.

On the basis of the initial concession and local custom and internship , as well as the influence of neighbouring charters, an extensive text was drawn up, known as the regional law de Vigueira et de Val de Funes, dated in the 13th century. The text reference letter refers to the fact that the regional law of the Rioja town of Viguera was granted to the infanzones of the valley of Funes and the regional law of Osma to the villains.

A late copy of this regional law , from the 15th century, is preserved in the Library Services Nacional de Madrid. It was edited by Hergueta and by Ramos Loscertales.

In Ramos Loscertales' edition, the text has 486 chapters. The rights and obligations of the infanzones, as a privileged group , and those of the villains, who also enjoyed great liberties, are set out separately.

Questions from Civil Law appear, but criminal and procedural rules predominate (different types of crimes and misdemeanours, judges, lawyers, solicitors, lawsuits, deadlines or means of test). Many chapters are also devoted to the Jewish population, which is explained by the existence of an important Jewish aljama.

The text was extended through the Funes valley to the towns of Caparroso, Torres del Río, Peralta, Rada, Murillo, Falces, Milagro, Aibar, Rocaforte, Ustés, Navascués, Castillonuevo, Lerín, Carcar, Azagra and Andosilla. The valleys of Roncal and Salazar have also been included, whose relationship with the valley of Funes, together with other localities, is the enjoyment of mountains and pastures in the Bardenas Reales. Lacarra differentiated between two series: the one grouped around the Funes valley, and the one derived from regional law de Logroño (Viana, Laguardia, San Vicente, Labraza, Aguilar, Lapoblación, Marañón and Bernedo).

Novenera is the name given to a peculiar legal district made up of Artajona, Larraga, Mendigorría and Miranda, to which was added Berbinzana, considered an aggregate of Larraga until the 15th century.

The term novenera refers to the novena, which consisted of the fruits that, after deducting the ecclesiastical tithe and equivalent to it, the farmers gave to the king in Aragon and Navarre.

Each of the aforementioned towns received its own regional law. In 1193, Sancho the Wise granted Artajona and Larraga a regional law that coincided in much of its content. Their inhabitants were required to pay an annual tax of one thousand maravedís, although they were exempted from other taxes, including the novena.

It was Sancho the Strong who granted his charters to Mendigorría in 1194 and to Miranda in 1208, confirming the charters of Artajona, Larraga and Mendigorría that same year, modifying the amount and the currency in which the annual tax was paid.

A common judicial internship was developed in the four localities, which was the basis for the extensive text known as the Fueros de la Novenera.

This text highlights the exemption of the novena and other contributions in exchange for the payment of an annual amount. Of course, fines and other penal sanctions were also paid. They had no other lord than the one appointed by the king; one man from each house served in the army, although if the king was called upon to defend the kingdom, they were all required to serve. surname The knights were not obliged to receive guests in their houses against their will; and jurisdiction was exercised by the king through a mayor or ordinary judge, who could be assisted by two good men. The text mentions the merino, whom the king could send to various encomiendas, as well as the baile, an official who was the proper executor. Civil matters (property, possession, sales and purchases, leases, real rights, obligations, inheritance and family), criminal matters (crimes and their corresponding penalties) and procedural matters are also regulated.

There are references of a local nature or specific to the area, such as allusions to the meseguero (guardian of the harvest) or the oath in San Esteban or Arribas.

The fact that the text does not contain corporal penalties or means of test has led to highlight its humanitarian tendency, although the death penalty by hanging for the traitor is included.

The text, which has 317 chapters, was edited by Tilander in 1951 on the basis of a manuscript of the late 13th or early 14th century preserved in the Library Services de Palacio in Madrid.

Both this text, relating to the legal system of a district(the Novenera), and that of the Funes valley, show a clear tendency towards territoriality, that is to say, towards overcoming localism or internship whereby each place had its own regional law or legal system.

This trend was logical as time went on and the different municipalities became more settled and expanded their relations with neighbouring localities. In other words, it was logical that the tendency was increasingly towards the creation of a uniform or more generally applicable law, a territorial law.

This tendency, common to all the kingdoms of the time, led to the drafting of texts that were of general application throughout the political entity in question. In the case of the Kingdom of Navarre, it led to the drafting of the regional law General.

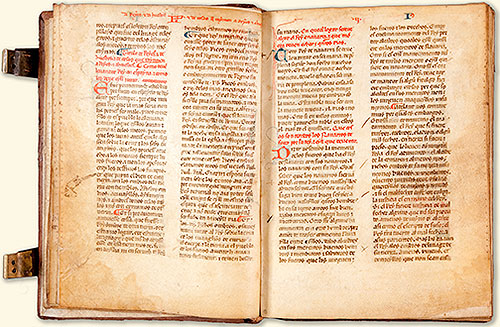

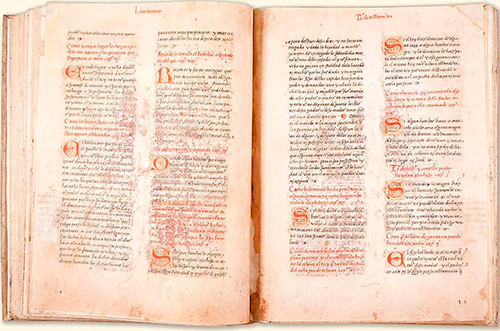

regional law General of Navarre. AGN, CODICES AND CARTULARIES

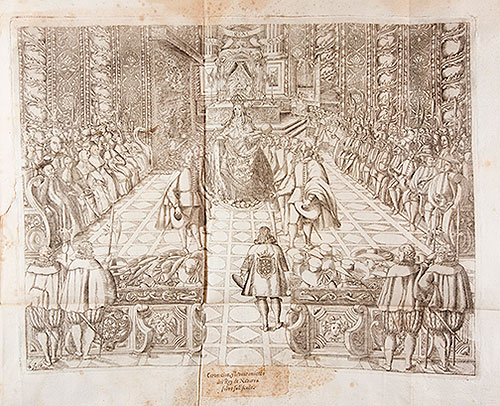

Engraving of the king's uprising of 1686. AGN, Library Services, FBA 49.

Book of Armoury of the Kingdom. AGN, CODICES AND CARTULARIES, F. 1.

It is undoubtedly the most representative text of medieval Navarrese foral law. On the one hand, because it was intended to include the law common to the whole kingdom and to be of general application and, on the other, because it is a text that regulates all branches of law in a much broader and more systematic way than the local fueros.

It was drawn up in the first half of the 13th century, apparently with the aim of acquainting Theobald I with Navarrese law.

In 1238, a commission was appointed, made up of the king, the bishop and forty other people, whose purpose was to put the charters in writing. The name of the author of the text is unknown.

What must have been the original or primitive part of the regional law is a set of twelve articles or laws known as regional law Antiguo. Among them, the first law of the text stands out, relating to the manner of raising the king, requiring him first to swear an oath to respect the fueros. The ceremony of the raising is described in detail: the king, on the day of his raising, will hear mass and receive communion; he will be raised by the twelve rich men, who will say three times "royal, royal, royal"; he will expand up to one hundred sueldos of his coin; and he will gird himself with his sword. Then the rich men shall swear to defend the king and the kingdom, to help him to keep the privileges, and shall kiss his hand.

The same law includes the limitation of a maximum of five in vayllía or non-Navarrese to occupy public posts in Navarre; that the king must have the support of committee of the twelve rich men or most important figures in the kingdom to make decisions that could compromise him (such as declaring peace or war); that the king will have his own seal and ensign, his ensign, and will mint new coinage.

This law was the basis of the constitutional system of Navarre, based on the king-kingdom pact. The king swore to respect the fueros and to improve them, not to worsen them, and Navarrese citizens were given pre-eminence to hold public office, except for the five non-natural persons that the king could appoint.

Also in this nucleus of the Oldregional law it was determined that the king should judge in the presence of three to seven rich men from the kingdom, and primogeniture was established in the succession to the throne.

The manuscripts of the regional law General, of which more than thirty are known, distributed in different archives, have been classified into three series of redactions: those known as A and B, which are asystematic, and C, which is systematic. In the latter, the contents are arranged by subject and distributed in six books.

The first book is devoted to political and social issues: the king's accession, the functions of the committee of the twelve rich men, the obligation to accompany the king in the host, the rights and privileges of the rich men and noblemen, and reference letter is devoted to the condition of the villains.

The second book is mainly devoted to Procedural Law (trials, lawsuits, summons, means of test, appeals), although it also deals with succession issues (primogeniture in the succession to the throne, the distinction between patrimonial and abolitory property, succession rights of children, freedom of disposal).

Contributions are the subject of the third book: services owed to the king and the church, exemptions or payment of censuses. Other subjects are also covered in Civil Law: sales and purchases, leases, pledges and bonds, donations and testamentary matters.

Family matters are, for the most part, the subject of the shorter fourth book, which deals with marriage, the arras, the need for the husband's consent, forces of women and adultery.

The fifth book is dedicated to Criminal Law (wounds, homicides, forces, robberies, thefts, falsehoods, insults, damages, with their respective penalties). Batayllas appear in this book as a means of judicial test : both those in which two villains confronted each other, equivalent to the duel between nobles, and the well-known ordeals in which divine favour was invoked so that it could be determined that someone was in the right.

The last book, the sixth, reference letter , deals with communal goods: the use of pastures, water and wood; the guardianship of the roads and fields; and the threshing floors. The last degree scroll of this book contains a set of seven fazañas, which, in this case, are folk tales with a legal moral.

The regional law General contains traditional institutions that are characteristic of Navarrese law, such as the testament of brotherhood, the truncation of property, the retracto gentilicio, the communities of faceras, the regime of conquests, the regime of the elderly relatives or the usufruct of vineyards. Many of these were already contained in the local fueros, on which the regional law General itself was based, also inspired by Navarrese custom and judicial internship , and even by some institutions of Roman origin.

Despite being inspired by the local charters, the fact is that the regional law General did not repeal them, except in the case of Pamplona: in 1423 Charles III the Noble decreed that the city would be governed by the regional law General in perpetuity and not by any other regional law.

In the other localities, the Generalregional law complemented the corresponding local regional law . As in many of them the regulation of some matters was scarce, as time went by, the application of the Generalregional law became generalised.

The regional law General is not known to have been sanctioned at the time, but the two amendments or updates to the text were sanctioned by royal decree: the first in 1330, under Philip III of Evreux, and the second in 1418, under Charles III. Of the first of these, the modification of the age that determined the capacity to act (from seven years of age to twelve for women and fourteen for men), and of the second, the remission of the penalty for casual homicide or the reinforcement of the value of the promise.

Several editions of the text of the regional law General have been made, including the first by Chavier, who included the text in his compilation of the laws of the Cortes published in 1686. Nowadays, the regional law General forms part of the legal tradition of Navarre, which has preferential status for the interpretation and integration of the current regional law Nuevo de Navarra.

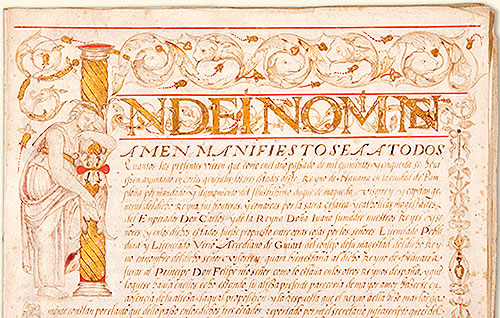

Oath of Prince Philip in 1551. AGN, CODICES AND CARTULARIES, B. 3.

After the conquest of Navarre by Castilian troops in 1512, the kingdom of Navarre remained an independent kingdom, awaiting the possible offspring that Ferdinand the Catholic might have from his marriage to Germana de Foix. As is known, they had a son, but he died shortly after birth.

Finally, in 1515, King Ferdinand decided to incorporate Navarre into the Crown of Castile. The fact of incorporation meant an important change since, from being an independent kingdom, Navarre became a kingdom integrated into a larger political entity, the Castilian Crown.

However, although Castile was a Crown of united kingdoms, which meant that all its constituent territories not only shared the person of the king, but also had the same institutions and the same law, Navarre was allowed to retain the status of a separate kingdom. This meant that it could retain its own institutions and its own law, sharing with the rest of the territories of the Crown only the person of the king. Thus, Navarre kept its own Cortes, its Diputación, its courts and its peculiar institutions not only as a kingdom, but also at the municipal and territorial level. This status as a separate kingdom was maintained until the 19th century, when the new centralist constitutional model would no longer allow any kingdom to survive within the new Spanish constitutional State. However, although with some parentheses, the peculiar status of Navarre survived until 1841.

As far as Navarrese law during this period is concerned, the laws drawn up by the Navarrese Cortes, which were collected in compilations, and the text of the regional law Reducido, are fundamental texts.

It is also worth mentioning the royal oath as a symbol of the peculiar condition of Navarre as a separate kingdom. All the kings, from Ferdinand the Catholic in 1513 to Ferdinand VII in 1817, swore to respect the fueros or Navarrese regime. If the one who swore was the viceroy in his name, the kings then ratified the oath. They swore to uphold the fueros and to improve them and not make them worse. On several occasions the Navarrese Cortes received the oath of the king and that of the crown prince, whom they in turn recognised.

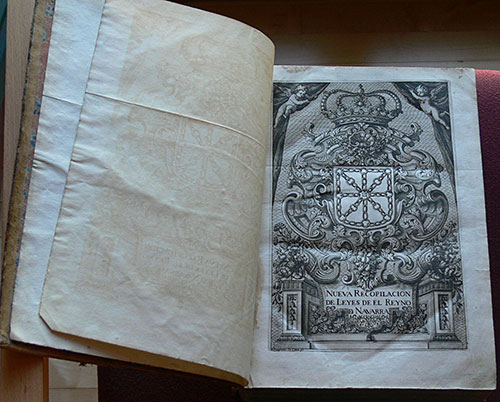

Compiled by Antonio Chavier. AGN, Library Services, FBH 1140.

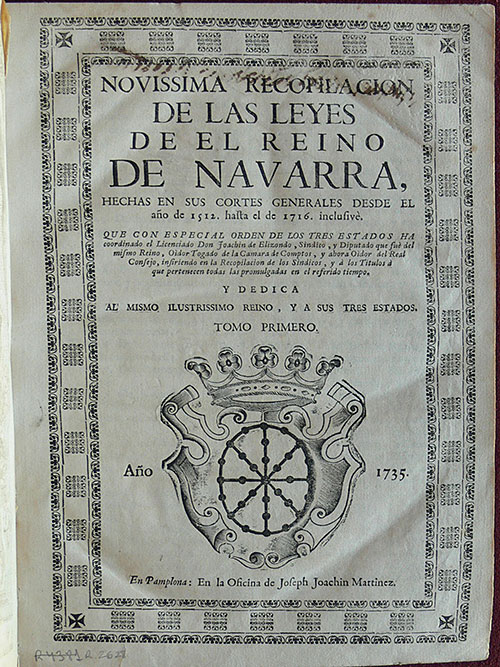

Novísima Recopilación de Joaquín de Elizondo. AGN, Library Services, FBH 1140.

The Navarrese Cortes acquired a strong personality following the incorporation of Navarre into Castile. They were responsible not only for receiving the oath of respect for the fueros from the king, but also for constantly ensuring compliance with them, claiming as contrafueros the actions of the king's officials that were contrary to the Navarrese regime. The contrafueros repaired by the king became laws, with a rank similar to those drawn up by the Cortes.

With regard to the laws dictated directly by the king, they were subject to a double control: that of the committee Real de Navarra, which from 1561 granted the sobrecarta, and that of the Diputación, which had to grant the foral pass.

The Cortes of Navarre were active until their last meeting in 1828-1829, although as time went by their meetings became more frequent. Thus, while in the 16th century they met on forty-one occasions, in the 17th century they met twenty-one times, ten times in the 18th century, and twice in the 19th century.

subject Each meeting approved the donation or contribution to be paid to the king and dealt with all kinds of issues, which gave rise to an extensive collection of laws of the Cortes.

In order to facilitate the knowledge and use of the laws drawn up by the Cortes, as well as of the grievances redressed, compilations were made throughout the Modern Age.

Compilations were characteristic legal texts of the Modern Age that collected the laws drafted both by the king and by the Cortes. Their purpose was to provide advertising and facilitate the knowledge of the laws that were being drafted, above all for the jurists in charge of applying and interpreting the rules.

Several compilations of laws were drawn up in Navarre, although only two became official. The reason for this is that the text required the approval of both the king and the Navarrese Cortes. For this reason, the first official compilation was late compared to those of other territories.

The compilations of Antonio Chavier and Joaquín de Elizondo were official.

The first was entitled Fueros del Reyno de Navarra desde su creación hasta su feliz unión con el de Castilla y Recopilación de las leyes promulgadas desde dicha unión hasta el año de 1685 and was published in Pamplona in 1686. This compilation includes laws passed by the Cortes of Navarre from 1515 to 1685 and also includes the text of the regional law General de Navarra, which was published for the first time in this work.

The second official compilation was that of Joaquín de Elizondo, which only includes laws of the Navarrese Cortes from 1512 to 1716. The work is entitled Novíssima Recopilación de las leyes de el Reino de Navarra hechas en sus Cortes generales desde el año de 1512 hasta el de 1716 inclusive. The text was published in 1735 and one of the most widely used editions is the one made by the Diputación Foral de Navarra in 1964. The contents are divided into five books, devoted respectively to public law, procedural law, civil law (contracts and last wills) and heterogeneous subjects (charity, public works and currency, among others).

In addition to these two official compilations, others were drawn up that did not obtain official status because they were not approved either by the king or by the Cortes of Navarre. These included the Old Ordinances of Valança and Pasquier, published in 1557, and a second text, by Pasquier alone, the New Ordinances of 1567, which enriches the content of the first. These two works contain, in addition to the laws of the Cortes and reparos de agravios, royal ordinances, laws of visit, tariffs, pragmatics, royal provisions, viceregal power, the form of leasing the royal boards and the formula for the oath of kings and princes.

In 1614, two compilations were drawn up simultaneously, one commissioned by the kingdom to its trustees, Sada and Murillo, and the other commissioned by the king, drawn up by Armendáriz. Both compiled the laws of the Navarrese Cortes, but neither had double approval, so they did not become official.

Also noteworthy is the text graduate Ordenanzas del committee Real de Navarra, drawn up by Martín de Eusa and published in 1622. It brings together diverse rules and regulations (pragmatics, laws of visit, agreed orders, laws of the Cortes or ordinances) related to the functioning of the Navarrese courts: committee Real, Corte Mayor and Cámara de Comptos.

Other compilations were that of Irurzun or the Repertorio by Ruiz de Otalora.

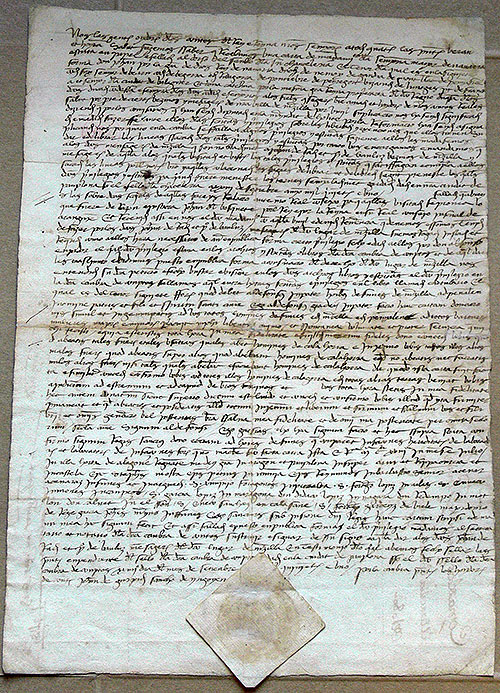

regional law Reduced. AGN, CODICES AND CARTULARIES, A. 8.

Once Navarre was incorporated into the Crown of Castile in 1515, the Navarrese Cortes considered it advisable to draw up a text that would update the old 13th-century regional law General and that would also include the institutions of the medieval local fueros that survived in the internship. The viceroy also proposed to the Cortes meeting in Tafalla in 1519 that a text should be drawn up that would compile the kingdom's fueros and ordinances.

In 1528 a commission was appointed to draw up the text, which by 1530 had already been drafted and was known as regional law Reducido, since it "reduced to unity" the various Navarrese charters, as explained in its preamble.

From that time onwards and throughout the 16th century, both the Cortes and the Diputación of Navarre constantly requested the approval of the text from Charles I and Philip II, without obtaining it. The underlying reason was political. Some members of the Chamber of Castile's committee and even some Navarrese jurists considered that approval of the text would safeguard Navarrese law.

The fact is that, despite not having received official sanction, the text was widely used in the internship by Navarrese jurists and officially became source interpretative and integrating of the Navarrese Civil Law from 1973 to 2019. In 2019, the regional law Reducido was excluded from the legal tradition of Navarre because it was not officially sanctioned at the time, which represents a great loss to the legal heritage of Navarre, especially when it was a text that had been used informally since it was drafted, especially because it allowed for the interpretation and understanding of many of the institutions included in the regional law General of Navarre, which has been maintained as part of the legal tradition of Navarre.

The text of the regional law Reducido contains 815 laws distributed in six books. The first is devoted to public law, beginning with the formula of the royal uprising, although it also deals with the convening of Cortes, defence of the natives, privileges of the nobility and the clergy, offices related to the administration of justice (mayors, jurors, lawyers, solicitors), control of accounts, and some local privileges (of Estella and Tudela) are included. The second book is devoted to Procedural Law, and contains material that is very new compared to the medieval fueros; the third book deals with family matters; the fourth book deals with Civil Law, in particular obligations and contracts; the fifth book deals with administrative matters (acquisition of neighbourhood, neighbourhood ordinances, pastures, felling, roads and water, among other subjects); and the sixth book deals with Criminal Law.

It is a text adapted to its time, which eliminates the anachronism of the medieval fueros, from which it draws its inspiration. The regional law General, the five families of Navarrese fueros, various ordinances, laws of the Cortes and even laws from visit were used in its drafting.

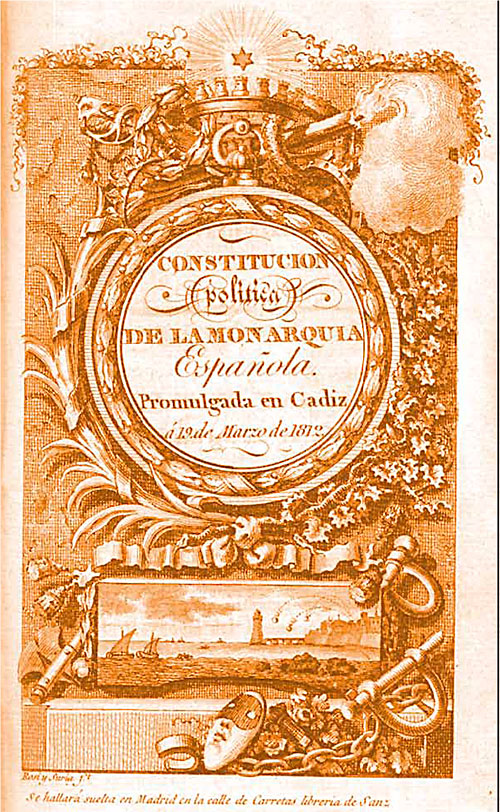

Constitution of 1812.

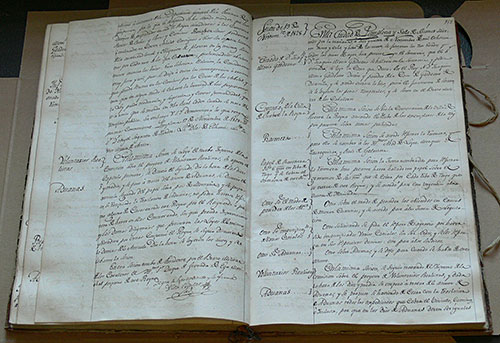

conference proceedings of the Cortes of Navarre of 1828-1829. AGN, Reino, Libros, conference proceedings de Cortes, no. 19.

Throughout the 18th century there were different moments of risk for the survival of the Navarrese regime. Navarre maintained its status as a separate kingdom within the Castilian Crown, which meant that it retained its own institutions and its own law (Cortes, Diputación del Reino, its own courts, its own laws), although, evidently, the laws of the monarchy were also extended to it, subject to the surcharge of the Royal committee and the foral pass of the Diputación.

The 18th century began in Spain with the War of Succession, which meant, for the territories of the Crown of Aragon (Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia and the Balearic Islands), the loss of the status of separate kingdoms that they had maintained since the creation of the Crown of Aragon in 1137. This meant the abrogation of their public law and, therefore, the disappearance of their own public institutions: Cortes, Diputació, their own courts. This abrogation took place through the Nueva Planta Decrees.

The fact is that, after those Decrees, the only territory of the Spanish Crown that retained the status of a separate kingdom was Navarre, a fact that posed a series of problems. These became visible at various points in time, of which three can be highlighted.

The first was when, in 1717, the abolition of inland customs, which hindered trade, was considered. Navarre maintained its own customs and a royal order stipulated that there should only be customs on the borders and in the ports. Navarre turned to the king to assert its loyalty in the War of the Spanish Succession and managed to have its customs reinstated in 1722. Something similar was raised in 1757, but customs were maintained until 1841.

Another delicate moment arose with the need for men for the army after the establishment of the quintas in 1772. Navarre managed to compensate for this with extraordinary economic contributions.

But the moment of greatest risk for the Navarrese regime arose when Godoy ordered the establishment of an office of royal vouchers in Pamplona and, in the face of complaints from the Diputación, a Royal Order was issued to suppress the fueros in 1796, overcharged by the Royal committee . While a board of Ministers examined the origin of the Navarrese fueros, Navarre offered extraordinary economic contributions. It is considered that the War of Independence made it easier for Navarre to preserve its regime.

The question arose again with the constitutional regime established by the Constitution of Cadiz. This constitutional text, although in its preliminaryspeech praised the Navarrese regime, ignored the status of kingdom that Navarre maintained and established that the territory of the nation would be divided into provinces, at the head of which there would be a provincial Deputation presided over by a political head.

This meant that the Constitution of 1812 was viewed with suspicion in much of Navarre. Once Pamplona was liberated in 1813, a Provincial Council was established there which, in 1814, on the return of Ferdinand VII, would once again become the Council of the Kingdom, when the traditional institutions were re-established.

During the Liberal Triennium, when the Constitution of 1812 was proclaimed, the Navarrese regime was once again suspended. In other words, the new constitutional system pointed to the end of the status of kingdom that Navarre had held since the High Ages average. This end would come, definitively, with the disappearance of the Ancien Régime.

The last meeting of the Navarrese Cortes took place in 1828-1829. After the meeting, the Government abolished the right of surcharges and ordered a commission to adapt the charters to the interests of the State.

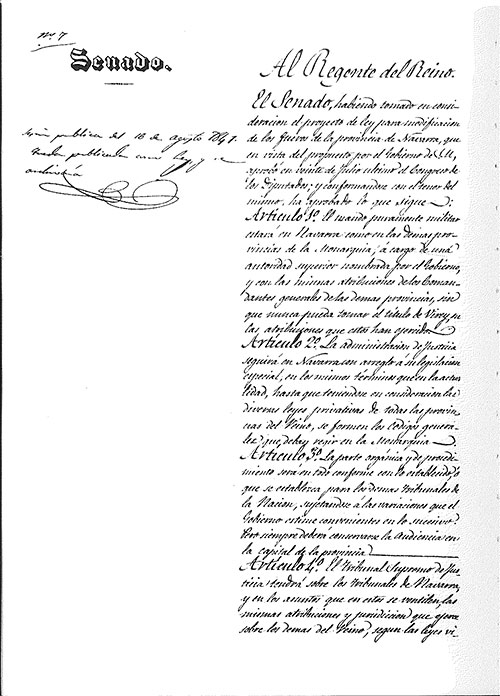

Facsimile reproduction of the Ley Paccionada published by the Ministry of Justice in Ley Paccionada de Navarra de 1841.

Homenaje al ministro D. José Alonso Ruiz, Ministerio de Justicia. administrative office General Técnica, Madrid, 2004. Study by Jaime Ignacio del Burgo.

After the death of Ferdinand VII in 1833, the Carlist wars began in the north of the peninsula. At the end of the first Carlist war in 1839, Espartero undertook to recommend to the Cortes that the fueros be preserved or modified, in contrast to the promise he had made in 1837 that they would be respected.

In that year, 1839, the Law of Confirmation of Charters was passed, by virtue of which the charters of the Basque provinces and Navarre were confirmed without prejudice to constitutional unity, and it was envisaged that these charters would be modified. It would be the Government that would propose the necessary modifications to reconcile them with the interests of the nation, first hearing the Basque provinces and Navarre, and reporting to the Cortes.

In the case of Navarre, the modification proposal was embodied in the so-called Ley de modificación de fueros, of 16 August 1841, also known as Ley Paccionada. The first to give it that name was precisely the Minister of Grace and Justice, José Alonso, in 1841. What is certain is that, throughout the negotiation of the text, both the documents issued by the Ministry of the Interior and by the Navarre Provincial Council referred to reference letter . agreement or to the agreed text, which, moreover, required the approval of the Diputación.

The Ley Paccionada has twenty-six articles that provide that the military service of the Navarrese will be the same as that of the rest of the Spaniards; the disappearance of the viceroy, whose military functions will be performed by a military chief; the establishment of a political chief appointed by the Government; the suppression of the Navarrese courts is confirmed, to be replaced by a territorial Audiencia; the special Navarrese legislation on subject on the administration of justice will survive until the general codes of the Monarchy are drawn up; it will be the Diputación provincial, made up of seven deputies elected by merindades, who will exercise the broad autonomy management assistant that Navarre maintains; The town councils were elected and organised as in the rest of the nation, although they exercised their powers of internal economic administration of the funds and properties of the towns under the dependence of the Diputación; the customs of the kingdom were abolished; a salt tobacco shop was established on behalf of the Government and a tobacco monopoly was established; The endowment of worship and the clergy is subject to the general law; reference is made to the exceptional status in which the taxation subject is left, establishing as the only direct contribution the amount of one million eight hundred thousand reals per year; and no novelty is introduced in the enjoyment of mountains and pastures in the common mountains.

The fact is that this law meant that Navarre lost its status as a kingdom. It became another province of the Monarchy, although it retained a special regime or regional law, which from then on would be known as the foral regime.

The viceroy, the Cortes, the military exemption and customs disappeared. By 1836, the Royal committee , the High Court and the Chamber of Comptos had already been abolished, replaced by a territorial Court, and that same year, in September, the Diputación del Reino had been dissolved, and the following month a provincial Diputación was established.

The foral regime that subsisted under the Law of 1841 was an economic-administrative system of its own that can be reduced substantially to competences in the tax and local regime spheres. Navarre maintained a wide-ranging autonomy in subject taxation and local administration. In the fiscal sphere, it can be considered to enjoy true sovereignty, given that the Diputación had School the power to set taxes, increase them, decrease them, create new ones and collect them, over all the towns of Navarre.

In subject of local administration, the new Provincial Deputation retained the powers of the Diputación del Reino in the administration of the products of the towns and of the province, as long as they did not go against the constitutional unity. The town councils, under the aegis of the Diputación, retained their Schools to administer the funds and property of the towns. The Diputación Provincial also had the powers which, being compatible with those retained by the former Diputación, were held by the other Diputaciones Provinciales, as well as those exercised until then by the committee Real in subject of administration and local government.

This new Provincial Council, with greater powers than the previous Council of the Kingdom, became the main institution of the new foral province.

From then on, the different conflicts that arose between Navarre and the State were motivated by the defence of this new foral regime at subject económico-management assistant which, on numerous occasions, was unknown or ignored by the State institutions.

One of the best known conflicts is known as the Gamazada, which took place when the Minister of Finance, Germán Gamazo, tried to extend the state tax system to Navarre in the project de Ley de Presupuestos para 1893-1894 (Budget Law for 1893-1894). There were official protests and popular mobilisations. After a huge demonstration in Pamplona, a protest was presented, backed by 120,000 signatures, the Protesta Foral. Gamazo was replaced and the law was passed with a conciliatory text. In commemoration of what happened, the Monument to the Fueros was erected on Paseo de Sarasate.

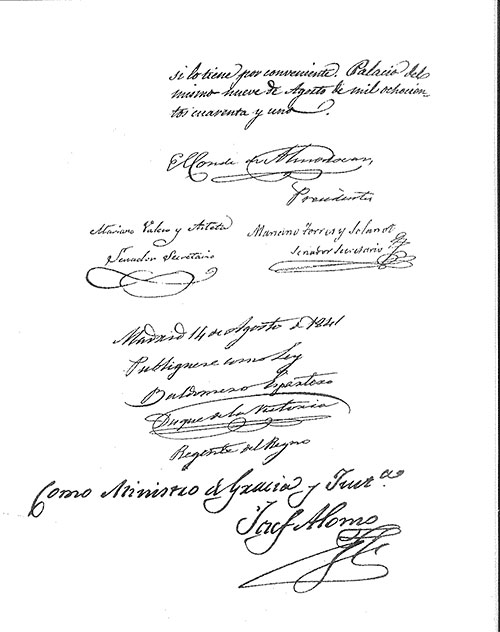

Spanish Constitution of 1978.

Navarre came to democracy preserving this foral regime that it maintained under the Ley Paccionada of 1841. This regime was also protected by the new Spanish Constitution of 1978, which established in its first additional provision that "the Constitution protects and respects the historical rights of the foral territories".

However, as is logical, it was necessary to adapt the Navarrese regime to the new Spanish political model , that is to say, the democratisation of the Navarrese institutions and their adaptation to the new design of a State of Autonomous Regions.

Shortly after entrance the Spanish Constitution came into force, the process of reform and improvement of Navarre's institutions began. In January 1979, the Foral Parliament of Navarre was created, which supported the continuation of the foral regime.

The "instructions for the Reintegration and Improvement of the Foral Regime of Navarre" and the "instructions on the election, composition and functions of the foral institutions" were approved on the basis of two drafts of instructions presented by the Diputación Foral, which were discussed and modified in the Navarrese Parliament.

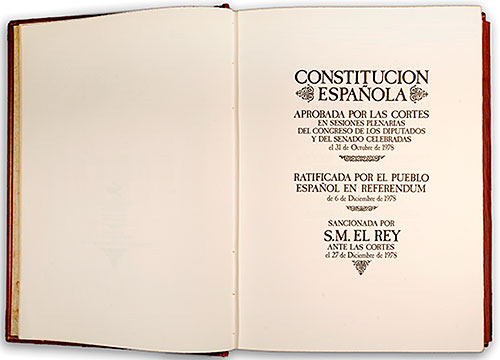

From then on, a period of negotiations began between Navarre and the State, culminating in the text of the Amejoramiento del regional law of 1982.

Improvement of regional law of 1982.

In December 1980, the negotiating commissions for the text were appointed, one by the Government of the Nation and the other by the Provincial Council.

The negotiations lasted until 8 March 1982, when it was agreed to submit the "Texto de la Reintegración y Amejoramiento del regional law" for consideration by the Government of the Nation and the Provincial Council for subsequent approval by the Spanish Cortes and the provincial parliament.

The Provincial Council approved the text on 9 March and it was ratified by the provincial parliament on 15 March. On 17 March, the Government of the Nation sent to the Cortes Generales a project of Organic Law that included the text C by the foral institutions. The congress agreed to process it through the single-reading procedure and discussion of totality, proceeding to its approval in the plenary session of 30 June of that year. The Senate processed it through the same procedure, approving the text on 26 July. bulletin Finally, the Organic Law on the Reintegration and Improvement of the Foral Regime was published in the Official State Gazette on 16 August 1982, coinciding with the 141st anniversary of the promulgation of the Law of the Foral Regime .

The text of this Organic Law, known as Amejoramiento del regional law of 1982, briefly refers in its preamble to the historical path followed by Navarre and highlights the agreed or agreed procedure that the reform of the Navarrese regime should follow.

The four titles into which the text is structured follow. The preliminary degree scroll sets out the basic principles of the foral regime and states that Navarre constitutes a Foral Community with its own regime, autonomy and institutions, indivisible, integrated into the Spanish Nation and in solidarity with all its peoples.

The first degree scroll is devoted to the foral institutions (Parliament or Cortes of Navarre, Government of Navarre or Diputación Foral) and their relations; the second to the Schools and competences of Navarre, as well as its relations with the State Administration and those of the other Autonomous Communities; and the third to the reform of the text, which cannot be modified unilaterally.

regional law New or Compilation of the Civil Law Foral de Navarra.

If in the field of public law Navarre has the Amejoramiento of 1982, in the field of private law it also has its own text: the so-called regional law Nuevo or Compilación del Civil Law Foral de Navarra, enacted in 1973 and whose last reform took place in 2019.

This text included Navarre's own Civil Law , responding to the need, which arose in the process of drafting the Spanish Civil Code, to include the foral civil rights that had survived throughout history.

At first, the elaboration of appendices to the Civil Code of 1889 was considered, but the system failed in the face of criticism of the Aragonese one, presented in 1925. appendix Aragonese Civil Code, presented in 1925.

In 1946, on the basis of a congress of Civil Law held in Zaragoza, it was agreed that each territory would collect its own Civil Law in Compilations.

In Navarre, the Compiling Commission was set up in 1948, but the work was slow and discontinuous. However, they were very agile after a meeting held in Roncesvalles in September 1959. In October of that year, the so-called regional law Recopilado de Navarra appeared, with three hundred laws and, although it was criticised on some points, the Compilation Commission was reorganised and charged with proposing to the Diputación the essay final of the text. The Commission submitted its report to the Diputación, which did not respond.

group In 1962, a small group of eight jurists (Aizpún, Arregui, d'Ors, García-Granero, López Jacoiste, Nagore, Salinas Quijada and Santamaría) began to draft a private compilation of the civil laws of Navarre, on which they worked for almost twelve years. In 1971, the text was elevated to a preliminary draft and published in the bulletin Oficial de la Diputación. Fourteen amendments were submitted and, after correction of the text, the Compilación del Civil Law Foral de Navarra or regional law Nuevo was approved by Law 1/1973, of 1 March.

The text has 596 laws, distributed in a preliminary book and three other books, which in the 2019 reform have become four. The text includes the peculiar system of sources of Navarrese law, recognising custom as the first source; the primacy of the will, expressed in the ancient principle of paramiento regional law vienze; and the institutions specific to Navarre in subject of persons and family ( reference letter is made to the House), donations and successions (the legitimate foral or the brotherhood will appear), and of real rights and obligations (communities of goods, facerías, helechales, dominio concellar or vecindades foranas are contemplated).

Since 1973, the text of the regional law New has been amended seven times, the latest and most extensive, affecting 190 of the 596 laws, in 2019. The reform has mainly affected family and inheritance law.

At present, the two representative texts of Navarre's own law are the Amejoramiento del regional law of 1982 in the field of public law, and the regional law Nuevo or Compilación del Civil Law Foral de Navarra in the field of private law.