St. Veremundo in his millennium

RICARDO FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA

Top of the entrance façade to the church of the monastery of Irache, presided over by the image of Saint Veremundo, c. 1700.

The historical figure of Saint Veremundo presents an abbot who governed the monastery of Irache, with success, between 1056 and c. 1093, making possible the acquisition of a rich patrimony, in the third quarter of the 11th century, under the reign of his great protector, King Sancho el de Peñalén (1054-1076). This monarch issued thirty-two deeds in favour of the monastery, while his predecessors issued fewer, namely Sancho el Mayor (†1035) on one occasion and García el de Nájera (1035-1054) on four. Cereal lands, vineyards, mills, small monasteries, forests and orchards came to belong to the monastic domain. The edition of the Irache cartulary by José María Lacarra in 1964 (republished in 1986), as well as the study by Ernesto García Fernández (1989) on the lordship of the monastery between 958 and 1537, are fundamental works for understanding what that house meant in medieval Navarre and the quantitative leap it took from the mid-11th century onwards.

At the time of Saint Veremundo, the Benedictine rule had only recently been introduced into the monastery, being recorded for the first time in 1033 and confirmed in the exchange of King García de Nájera and Abbot Munio in 1045, in which it is stated that the monks served God under the rule of Saint Benedict. From then on, Irache's trajectory grew until it became the second monastery in the diocese of Pamplona.

The work of assisting pilgrims is a noteworthy aspect of the times of Saint Veremundo in Irache, since in 1054, King García el de Nájera founded one of the oldest hospitals on the Pilgrim's Way to Santiago, at the gates of the monastery, giving a field that had been used as an oak grove for its support. Its importance must have declined very soon due to the importance of the hospital that was built in the city of Estella.

So much for the synthesis of his historical figure, but the life of the saints did not end with his death. As Teófanes Egido reminds us, after leaving the earthly world, another decisive stage in his historiography began: that of the production and reception of his transfigured figure. In this last chapter, it should be remembered that what we know about the veneration, miracles and iconography of Saint Veremundo comes from sources dating from the Modern Age, coinciding with the monastery's membership of the Congregation of Saint Benedict of Valladolid. Among the abbots who claimed the saint as a sign of Irache's identity, or were protagonists of events that promoted his cult, three stand out. The first, Friar Antonio de Comontes who, following his cure in 1583, ordered the saint's remains to be transferred to a polychrome wooden casket made ad hoc over the following two years. The second abbot was a Navarrese from Sada, Fray Pedro de Úriz, who became the driving force behind the construction of the Baroque chapel, its altarpiece with courtly resonances and a rich silver urn for his relics, actions that he tried to carry out fill inwith the elevation and extension of his feast day, requesting it from the Holy See, in a context in which the co-patrons Saint Fermin and Saint Francis Xavier seemed to have obscured or displaced the figure of Saint Veremundo, who, in his opinion, deserved other consideration as the only saint in the Kingdom who was born and died there, his relics also being preserved in Navarre. The third of the abbots was Fray Miguel de Soto y Sandoval, abbot between 1761 and 1765, and professor and canon of his university from 1756. The publication of his text on the saint saw two editions in the 18th century, in 1764 and 1788, at a time when the Cortes of Navarre successfully requested the extension of the cult of the saint to the whole of the Kingdom of Navarre by Rome (1767), when a couple of decades had passed since the Pamplona prelate Don Gaspar de Miranda y Argaiz had done so for the whole of the bishopric of Pamplona.

In this digital exhibition, together with some pieces linked to the saint and his report-singularly hagiographies, images and prints, his disappeared chapel, etc.-, we have tried to contribute, from what is already known and from many other documents, some unpublished, to knowledgeof what his figure meant in the imagination and in the collective conscience of the people of Tierra Estella.

In recent decades, the commendable work of the associationof Friends of the Monastery of Irache on numerous occasions has made it possible to make known, through its many educational activities, aspects of the life and reportof the saint over the centuries, also sponsoring some fundamental facsimiles for the history of that historic monastery and its emblematic saint. This digital visitof the Chairde Patrimonio y Arte Navarro is dedicated to them.

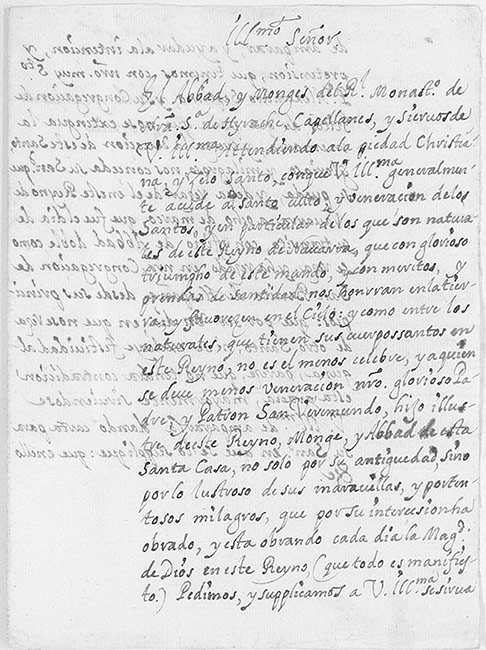

Petition of the abbot of Irache for the extension of the cult of St. Veremundo in 1657. fileGeneral of Navarre.

The cult of Saint Veremundo spread through various authorisations from the bishops of Pamplona and the Congregation of Rites in Rome. At first, it was the monastery that worshipped him, with its own mass if we are to believe the monks, followed by the Congregation of San Benito in Valladolid. Throughout the 17th century, attempts were made to extend the scope of his feast day, but these did not bear fruit until 1745, when the bishop of Pamplona decreed, not without contradictions, the extension of his feast day to his bishopric. Finally, in 1767 it was authorised for the entire kingdom of Navarre, at the request of the Cortes of the Kingdom itself.

Little is known of the celebration before the 16th century. The Irache Lectionary, composed in 1547 or a little later, includes in its texts dataand miracles attributed to the saint. In 1591 Pope Gregory XIV granted a plenary indulgence for five years to all the faithful who, having gone to confession and received Holy Communion, visited the monastery church on 8 March, the feast of St. Veremundo. Similar papal privileges, for different periods of time, were granted in 1614, 1646, 1704, 1712, 1745, 1763 and 1773.

fileOne of the great supporters of his cult at the beginning of the 17th century was the Benedictine bishop of Pamplona, Fray Prudencio de Sandoval, who in 1614 ordered the collection of testimonies about his birth, reputation for sanctity, celebrations and cult, etc., information which was carefully kept at filede Irache and which later passed, together with several papal Briefs, to the parish of Arellano, where it was inventoried in 1899 by the parish priest Mamerto Urmeneta. Today we have not been able to locate this important documentation.

The popularity of the saint was not unrelated to the great rogations on the occasion of stubborn droughts, as occurred in 1650, when the abbot of Irache organised an extraordinary procession to the Virgin of Rocamador in Estella, which ended with the desired rains after a long period of drought. In that year, according to the testimony of Cardinal Aguirre, who lived in Irache between 1657 and 1661, and was therefore very close to those events: "there was no image of devotion in the Kingdom, nor any shrine, to whom people did not turn for remedy, but the sky was always arid and dry". In 1664, the aforementioned cardinal reported that entire villages and processions arrived at the temple with very rigorous penitence, with men of all conditions "giving themselves to averagenight, lamps extinguished, cruel scourging, sobs rang out, sighs resounded and represented to our eyes a vivid image of the Ninivites...". The relics of the saint were again carried in procession and the longed-for rains were obtained.

It is no coincidence, but rather they obey a specific cause, the petitions for the cult of the saint that the clergy of Navarre and the Diputación of the Kingdom made to Rome, at the request of the abbot and monastery of Irache, in 1657. That year saw the end of a bloodless war in Navarre between supporters of Saint Fermin and Saint Francis Xavier for the board of trusteesof Navarre, with the Solomonic decision of Alexander VII declaring them both co-patrons. From Irache, its monks contemplated how all this could leave Saint Veremundo in a very secondary position. The abbot at that time, the Navarrese friar Pedro de Úriz, did all he could between 1654 and 1657 to make Saint Veremundo shine with the construction of his chapel, splendidly, with a gilded altarpiece Aand a silver urn in which his venerated relics were transferred. To crown these efforts, he tried to increase his cult, always arguing that he was a Navarrese saint who, unlike others, had died in the kingdom and his remains were still there, as well as for other reasons.

In April 1745, Bishop Miranda y Argaiz decreed the extension of its recitation to the whole of the Bishopric of Pamplona. The aforementioned prelate made that decision without communicating anything to the cathedral chapter, which did not learn of the episcopal decision until it appeared in the galloph of 1746.

In 1765 a further step was taken in the extension of their cult. The abbots of Irache and Fitero asked the Cortes of Navarre, meeting in Pamplona, to urge the Sacred Congregation of Rites to obtain the extension of the cult of Saint Veremundo and Saint Raimundo of Fitero throughout the Kingdom of Navarre. The town of Arellano established the novena to the saint in that same year of 1765, with attendanceof its municipal authorities, as a town body, with all formality and punctuality.

A few years later, the Diputación del Reino reported, at the following meetingof the Cortes, in 1780, how the mandate of the previous Cortes had been positively resolved and how the Offices of both saints - Raimundo de Fitero and Veremundo de Irache - had already been printed for years. Indeed, this had been done in May 1767, when a Brief of Clement XIII approved the request, extending the cult of both abbots to the whole Kingdom, as attested by Don Manuel de la Canal, vicar general of the diocese of Pamplona in July 1767.

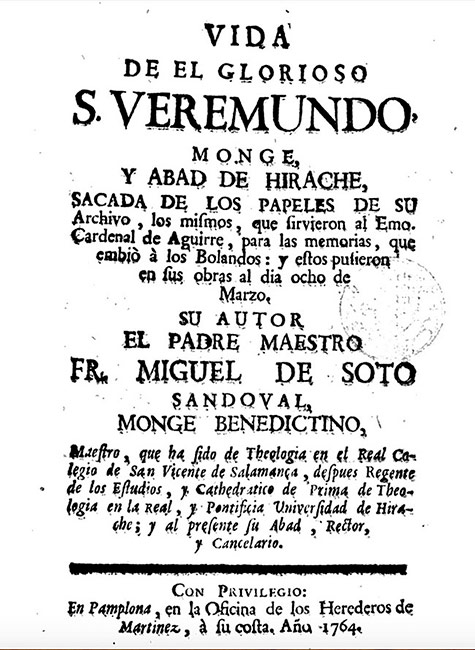

Vida de san Veremundo por el abad fray Miguel de Soto Sandoval, Pamplona, Herederos de Martínez, 1764.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the famous historian of the Benedictine order, Friar Antonio de Yepes published, in Irache, the first three volumes of his Coronica general de la orden de San Benito. In the third Issue (Nicolás Asiain, 1610), he refers to the saint as "honor of Navarre and luster of this holy house", relating his life and miracles, taking advantage of news from his file and the Lectionary of the monastery of 1547.

The most universal knowledgeof his figure was due to the inclusion of his biography in the March volume of the certificate Sanctorum, in 1668, the work of the Bolandos, groupof ecclesiastical writers, mostly Jesuits, associated to purify the lives of the saints. They took the name of Van Bolland (1596-1665) or Bolando, a hagiographer of the Society of Jesus. The materials relating to St. Veremundo were prepared by the future Cardinal José Sáenz de Aguirre (Logroño, 1630 - Rome, 1699), who entered the Benedictine order in 1630 at San Millán de la Cogolla and completed his trainingat the University of Irache, where he obtained the Degreesof high school programin arts and theology and explained those disciplines between 1657 and 1661.

In the second half of the 18th century, coinciding with the requests for the extension of his cult to the whole kingdom of Navarre, the abbot of Irache, Fray Miguel de Soto Sandoval, published a Life of Saint Veremundo ( 1764) in the Pamplona presses of the Herederos de Martínez - in reality, of Miguel Antonio Domech - accompanied by a print of the saint in Benedictine habit, with crosier and mitre at his feet, by the Aragonese engraver José Lamarca. The dedication to the Kingdom of Navarre, with its coat of arms engraved by the silversmith Beramendi and a flowery text by Miguel Antonio Domech, is a plea in favour of the saint and his cult, with numerous quotations, including one to Father Moret, recalling that he was "the only son of Navarre who left his holy body there". The prologue is by the author of the book and in it he indicates his intention:

Buildingof the faithful and to excite devotion to the saint... what has moved me most to write this Life, is the knowledge that many in this illustrious Kingdom of Navarre still do not know if there is a saint Veremundo in the Church, being as he is a native of his own country, in life its special protector and in death the only one of the saints of Navarre, who for the comfort and refuge of his countrymen, left his relics here... These circumstances, the ignorance of which has been the cause of a cooling of devotion for some time now, coming to the attention of all, will make the people of Navarre return to the fervent devotion that their elders had for this saint and in return they will obtain through his intercession the favours that they experienced.

After the 1764 edition was sold out, it was republished in 1788 in the Pamplona printing house of Joaquín Domingo, without the flowery dedication of Domech and without the prologue of the author of the book, but of the abbot of the monastery, Fray Manuel de Hiebra. Father Miguel de Soto, author of that Life of St. Veremundo, was abbot of Irache between 1761 and 1765, and professor in his university since 1756. Previously he had taught theology in Salamanca. After leaving the abbey dignity, he continued to live in the monastery as a retired Full Professor . According to Ibarra, he was introduced by Father Domingo Ibarreta, paleographer and professor at Irache between 1745-1749, and from 1765 onwards in the study of diplomatics together with the deeds of the abbey, which would give rise to his monograph on the saint.

The biography of Abbot Soto was republished, belatedly, in 1899, in an edition prepared by the learned priest of Muniáin de la Solana, Pedro Velasco y Martínez de Arellano, who died in 1893 and was a great scholar of topic, as evidenced by the texts he added to the original, studying many materials from different archives and the cult of the saint in Villatuerta, Arellano, Estella and other localities. This conscientious study was used for other monographic texts published throughout the 20th century. We will mention some of them that contributed with their researchnew news: firstly, the conscientious workby Miguel Imas, parish priest of Arellano, which he anonymously entitled Glorias Navarras. Homenaje a un navarro esclarecido. Saint Veremundo Abbot of Irache. Traslación 1926; and with regard to Villatuerta, the monograph by Eduardo Ibáñez: Esbozo histórico de la villa y parroquia de Villatuerta, published in 1930, contains interesting news about the cult of the saint in that town.

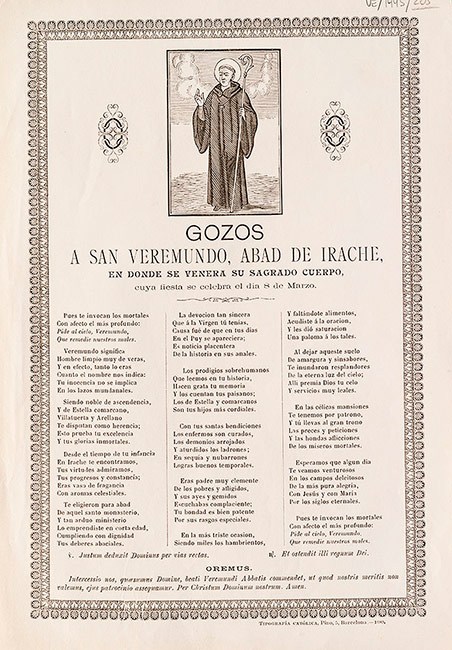

Gozos a san Veremundo, Barcelona, Tipografía Católica, 1889. Photo: Library ServicesNacional.

The word 'gozos' comes from the Latin gaudium, meaning joy. As such, we identify folio-sized printed matter in which the sacred image is combined in different types of engraving, usually small woodcuts, together with versified compositions to be sung on festivities, in which memorable events, virtues and miracles are recorded in all subjectof calamities, illnesses, epidemics, wars, droughts and plagues. They are a testimony to the weight of the religious and devotional image at all cultural levels, aimed at the praise and exaltation of the icons represented, generally the Virgin and the saints. As Díez Borque points out, this is a structural associationof image and verse, in which the image is not a simple ornament or illustration of the poetry, but its relationship with refrains and couplets is profound and meditated. The great Marian devotions and popular saints in Navarre had their own gozos and letrillas, which were incorporated into their novenarios. On the other hand, their publication in loose printed form is not frequent, as we have recently shown when we catalogued thirty-two of them, including those of St. Veremundo.

The 19th century saw the departure of the saint's relics from the monastery, with agreements for their safeguarding and veneration between the two towns that dispute his birth, Villatuerta and Arellano, which periodically shared them. In 1889 his life was republished with long appendices by Pedro Velasco y Martínez de Arellano, once the Piarists had settled in Irache, at a time that may coincide with the edition of the Gozos preserved in the Library ServicesNacional, also dated 1889, in the printing house of Tipografía Católica in Barcelona. The first was published in 1879 by the prior of El Puy José María Arrastia, the same prior who commissioned a sculpture of the saint from Barcelona in 1876 for the aforementioned sanctuary of El Puy. The second was published on the initiative of the Piarists in 1895 and the third is included in the reprinting of the hagiography of Saint Veremundo de Soto y Sandoval, reprinted on several occasions.

The 1889 Barcelona print of the Gozos incorporates the image of the Benedictine saint, which basically follows the iconographic modelof the eighteenth-century engraving by José Lamarca, to which we have alluded from 1764, with the saint in the black Benedictine cowl, accompanied by the abbatial insignia of the crosier and pectoral. The lyrics of the Gozos do not correspond with the primitive ones of the 18th century published together with the reprint of his life by Soto y Sandoval, in 1788, nor with those of the later novena of 1895, published when the Piarists had already become positionof the monastery, specifying that they were sung at the time of the veneration of the saint's relic. On the other hand, they do coincide with those that appear in the novena by the aforementioned José María Arrastia, referred to above and published in Pamplona by Sixto Díaz de Espada in 1879, one of the very rare copies of which is kept in the Fundación Universitaria Española. The novena also includes a simple wood engraving of the saint that copies the intaglio by José Lamarca and illustrates the aforementioned biography of the saint from 1764.

The date of publication in 1889 brings us to the opening of his urn in Arellano, in an atmosphere of exaltation, as the centenaries of his death were celebrated with great solemnity in Villatuerta (1892) and Arellano (1899). The refrain asks the saint for protection from all kinds of evils subjectand its twelve verses describe his way of being, his birth, disputed between Villatuerta and Arellano, training, virtues, his election as abbot, Marian devotion, the appearance of the Virgin of El Puy in his time, cures, prodigies for the benefit of the crops, charity, the miracle of the dove and the satiated hungry, as well as his glorious passing. The text is arranged in three columns and includes a typographic border. The woodcut engraving sampleshows the Benedictine abbot, without any particular attributes.

Interior of the chapel of San Veremundo built between 1654 and 1657 and decorated with plasterwork in 1701. Photo: Catalog Monumental de Navarra.

It was probably the first Baroque chapel erected in our monasteries for images of great worship, such as that of San Bernardo in Tulebras, the Cristo de la guidein Fitero or San Marcial in Azuelo. If the cities competed in the centuries of the Baroque with the chapels of their patron saints, the monasteries did the same with those of their saints and venerable relics. The managerand mentor of the projectof the chapel of San Veremundo was Fray Pedro de Úriz, an abbot from Navarre who governed the monastery of Irache between 1653 and 1657, a virtuous and learned monk, a native of Sada and previously abbot of Nájera between 1649 and 1653. The construction of the chapel and its decoration, as well as the transfer of the relics to the silver urn during his rule, are events that must be seen in relation to the monastery's desire to vindicate its saint. He influenced the clergy of Navarre and the Diputación of the Kingdom to send petitions to Rome in 1657, the same year in which the Roman Pontiff had sanctioned the co-patronage of St Francis Xavier and St Fermin for Navarre. This fact and its prolegomena gave rise in the abbey of Irache to a claim to Saint Veremundo, as he was a native of the Kingdom and his relics were there.

In the middle of the 17th century, it was decided to build a large chapel with a combined floor plan. In November 1654, after licenceby Fray Bernardo Ontiveros, General of the Benedictines, the works were auctioned off for 1,700 ducats. José de Gurrea, Gonzalo Ruiz de Galarreta and the Riojan Miguel Martínez and his son Juan with the famous Juan Raón attended the auction. The latter three made the best bid and were awarded the work on the chapel "next to the church, with its orange averageand burial of the monks", for the sum of 1,400 ducats. A design, preserved in the fileReal y General de Navarra, with the plan and elevation of the chapel that corresponds to the aforementioned contract. It is initialled by the notary and the abbot, Friar Pedro de Úriz. It has a very simple combined floor plan with a small rectangular section, covered by a groined vault, and another square section to support the large dome. The enormous buttresses of the chevet and the elevation with plasterwork in the frieze and large flaming fleurons on the sides of the roof, above volutes, are striking. It is likely that this floor plan came from Madrid, and must be related to the person who, at that time, was the monk to whom the works of the monasteries of the congregation were delegated, Friar Esteban de Cervera, whom we will deal with when we deal with the altarpiece of the chapel, now in Dicastillo, whose designbelongs to him.

A later contract signed in March 1655 with Miguel Martínez, his son Juan and Juan de Raón, master builder, modified some aspects of the previous contract agreementand set its completion for the feast of St. John the Baptist in 1656. The changes mainly affected the slightly larger size, the elimination of the large buttresses and the adoption of a slight Latin cross at the chancel, with small open chapels at the front. Those spaces were covered by a half-barrel section with lunettes and another with a dome.

The construction of that space, which was incomprehensibly demolished in 1982, was richly decorated in 1701 with colourful plasterwork by Vicente López Frías, the same master who was responsible for the façade of the basilica of San Gregorio Ostiense and the plasterwork decoration of the chapel of San Andrés, patron saintof Estella, in the parish church of San Pedro de la Rúa. Its interior featured a series of large paintings, probably passages from the life of Saint Veremundo, the work of the Aragonese painter and member of the clergyestablished in Soria, Juan Zapata Ferrer (1657-1710), who specialised in fresco mural painting and was the author of the paintings of the Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Loveof San Saturio in Soria.

A magnificent altarpiece, contracted in 1655, a great novelty in the regional panorama, presided over the ensemble. Fortunately, it has been preserved and we will deal with it in another sectionof this virtual visit. To complete the project, in 1657 a new silver urn was placed with the relics of the saint, in keeping with the sumptuous space. The piece disappeared in 1813, in the context of the War of Independence. Various silver lamps and twenty-six paintings adorned the walls of the chapel. The interior of the chapel was also adorned with another complement of the time, the beautiful hangings for special days. They are described in detail in the inventory of the monastery's sacristy in 1680.

Altarpiece of Saint Veremundo in the parish church of Dicastillo, from the monastery of Irache and built by Gil de Iriarte in 1655, with designby Friar Esteban de Cervera. The gilding of the piece was done by positionGregorio Gómez and Francisco de Astiz. Photo: Calle Mayor.

The new altarpiece for the chapel - preserved in Dicastillo - was also made with the permission of the General of the Order, as recorded in a certificateof the monastic chapter. It is a very unique piece in its typology, distinctly Madrilenian. It was made from December 1655 onwards by Gil de Iriarte, following the design designof Friar Esteban de Cervera, a distinguished Benedictine master who worked for various monasteries. The gilding of the piece was done by positionGregorio Gómez and Francisco de Astiz. A portion of its original design, corresponding to the part of the attic, has been preserved in the fileReal y General de Navarra, from the filede Irache.

Although the altarpiece has been identified with the one made in 1613 to place the ark of relics "in the arch of the church, where the sepulchre is, in front of the door of Wayside Cross", the reality is that in that year, its author, Juan III Imberto, did not use the architectural language of the altarpiece contracted in 1655, of clearly Madrid resonances and foreign to the prevailing Romanism with Vignolesque architectures. In reality, most of the 17th century decorative works and projects in the monastery looked to Castile or Madrid, either to the monastery of San Millán de la Cogolla, or to the works of tracists highly influenced by the Court, where the best art was consumed. The only comparison of the altarpiece of San Veremundo with the Navarrese panorama of the time is the one that can be made with the altarpieces of the Barbazana, the work of Mateo de Zabalía (1642).

accredited specializationThe author of the design deserves a special mention, rather than its material executor, who was well known in the Estella workshop of the mid-17th century, whose activity is documented in places such as Cirauqui, Los Arcos, San Martín de Améscoa and Labeaga. Friar Esteban de Cervera was a conventual of the monastery of San Juan de Burgos where he worked, as well as in San Martín de Madrid, San Vicente de Salamanca and San Millán de la Cogolla. In 1649, together with Brother Francisco Bautista, a Jesuit, and Brother Francisco Cruz, a Trinitarian, he appraised the wood that Pedro de la Torre worked on for the ephemeral architectures for the reception of Mariana of Austria. But it is undoubtedly his authorship of the altarpiece of San Millán de la Cogolla in 1656, executed at the same time as that of San Veremundo, with which he shares the same style, his most outstanding work, which in Begoña Arrúe's opinion can place him in a position of great relevance in the designof the Spanish Baroque altarpiece.

The contracts with Gil de Iriarte and the painters Francisco Astiz and Gregorio Gómez were signed on 22 December 1655; the former was to have everything finished by October 1656 and the latter by Christmas of the same year. Gil de Iriarte was to be paid 400 ducats in four instalments and undertook to use sound pine or walnut wood, free of knots and moths. The polychromators were obliged to submiteverything perfectly gilded and to give fine colours to the capitals, fleurons and cartouches, following the terms of Gil de Iriarte's deliveries, corresponding to the parts of the altarpiece. The two coats of arms at the ends of the attic with the royal arms and those of the monastery - now lost - were to be painted to perfection.

The altarpiece and the preserved part of the design essentially coincide and the designis by Friar Esteban de Cervera, as we have already mentioned. The piece is in line with what Alonso Cano, Pedro de la Torre and Brother Bautista were doing at the Court, with great power in the architectural and decorative elements, the latter of which are volumetric and fleshy. It consists of a bench with corbels of large acanthus leaves, a single body articulated by pairs of columns with composite capitals whose shafts are decorated with vegetal elements in the first third, the rest of which is fluted, and an attic topped by a curved pediment and flanked by multiplied pilasters and enormous buttresses. The details of the acanthus leaves, the festoons of fruit, the rosebuds and the modillions have obvious parallels with the aforementioned main altarpiece at San Millán de la Cogolla. The coats of arms that were mounted plumb with the extreme columns have disappeared and the central niche that housed a large carving of Saint Veremundo with the silver urn, which disappeared in 1813, was greatly altered when the piece arrived from Irache in 1842.

Although the coats of arms have disappeared, a photograph published in the magazine La Avalancha, the original of which is preserved in the Photo Library of the fileMunicipal de Pamplona, shows that they contain the arms in four quarters, as in the Renaissance cloister, in imaginary armouries of the monastery, which even included the legendary protectors of the abbey. In the first quarter are the fiery ribbons that recall Íñigo Arista and his successors, as the Prince of Viana stated that, just as the arista close to the fire is lit, so that monarch, seeing the Moors at close quarters, would light up to fight them. The second sampletwo abarcas in memory of Sancho Garcés II, for having been his arms. On the third were the lilies with a quotation of the Evreux and on the fourth the chains of Navarre.

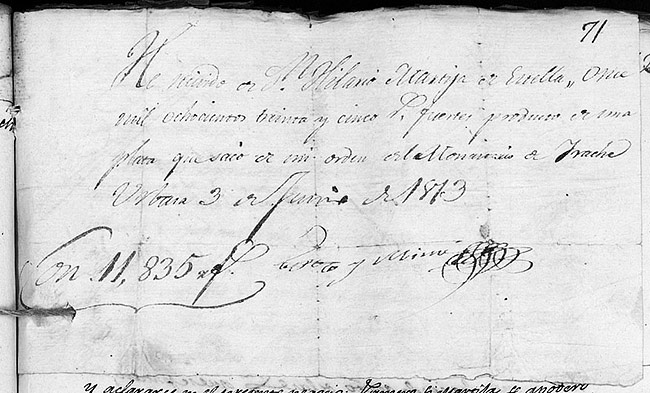

receiptin favour of Hilario Martija, initialled by Espoz y Mina, for the proceeds from the sale of the urn of St. Veremundo and other silver pieces from the monastery of Irache, in June 1813. fileRoyal and General of Navarre.

The urn made of silver in 1657 is described in that year as "curious and rich". According to the Bolandists' text, it was extremely heavy and could barely be carried by four sturdy young men: "pretiosam admirabilis structurae structurae urnam ex puro argento formata, quem portare vix quatuor iuvenes robusti sufficiunt". It cost 7,580 silver reales, while the gilded altarpiece cost 8,800 and the construction of the chapel 19,741.

At the beginning of the War of Independence, when the monks of Irache had to leave their monastery for the first time, they decided to hide part of the silver of their trousseau and the silver urn containing the relics of the saint, in order to "save them from the outrage, theft and contingencies to which they were exposed in the turbulent and licentious days of the war". The following account has been partially copied, without much detail, since it was first made known in 1899 in a text by Pedro Velasco, a priest from Muniáin de la Solana. The enquiryof two trials at the fileGeneral of Navarre and another at the fileDiocesan of Pamplona, which José Luis Sales put us on the trail of, have enabled us to clearly reconstruct some real events that seem to have been taken from a novelistic tale.

In September 1809, before the departure of all the monks, Brother Antonio Mosquera, steward, and Brother Benito López entrusted two servants of the monastery -José Hugarte, a native of Zúñiga and Antonio Ruiz, from the Santander Mountains- with the transfer of the ark and other silver pieces (two lamps, a censer and a virile) to the house of Don Tomás Sanz, vicar of Igúzquiza. They carried out their task without incident at averageat night and on horseback. In order to completely mislead possible witnesses, the aforementioned Friar Antonio Mosquera had already taken measures, as he took advantage of the opportunity given to him by Commander Cuevillas (Ignacio Alonso de Cuevillas, 1764-1835) the previous year, 1808, to pretend to take the urn to Castile, so we assume that, between 1808 and 1809, the piece was hidden in the monastery.

On that autumn night in 1809, the vicar of Igúzquiza received the urn and hid it, provisionally, in the hayloft. But very soon, after six or seven days, and from agreementwith the village farmer Antonio Lisarri, they hid it in the upper part of the house, in an attic room that could also be accessed from the house of their neighbour Diego Arellano. After making a hole in the main wall and inserting the urn, they partitioned the place with the utmost secrecy.

It remained there until the end of September 1812, when, for fear of the French, a daughter of the aforementioned Diego Arellano, named Antonia, went to hide some pieces in the upper part of her house, for which she forced a window and, accompanied by a candle, entered the dark place where the urn was, being surprised by the findingand the brightness of the silver. Frightened and being alone at home, she went to look for Gabriel Irisarri, a student, and they both returned, recognising the saint's ark because they had seen it before in the monastery, particularly Gabriel Irisarri, who had lived in Irache as a student and relative. Antonia immediately went to tell the vicar, Don Tomás Sanz, who replied that "she should not be so surprised, because he knew what it was and who had placed it there".

In March 1813, the indiscretion of some of those mentioned so far meant that the news reached the ears of Hilario Martija, innkeeper of Estella, the same man who on 14 October 1809 had saved Javier Mina el mozo from being captured by the French, hiding him in his house and providing him with a disguise to leave Estella at night on the road to Urbasa, which cost him a long imprisonment in Pamplona. Hilario Martija was well aware of everything that was happening in Irache, as he had been appointed managerfor the conservation of the monastery by Ramón Espoz, commissioner of national assets, in 1813.

According to Martija, he always proceeded on the orders of General Francisco Espoz y Mina and with the permission of the Provisor Don Miguel framework. After ascertaining the whereabouts of the piece, he went to Igúzquiza and located it. The following day, he ordered the Pamplona silversmith Miguel de Cildoz, who lived in Estella, to go to portal de San Nicolás, where his servant would be waiting for him, without saying where they were going and with the sole warning that he should be equipped with the tools of his profession as a goldsmith. Once in Igúzquiza, Martija ordered a Mercedarian from the convent of Estella, Fray José Arcaya, to extract the relics, while the silversmith was given the task of dismantling the silver urn, whose plates, with other pieces, were placed in a seron, taking them to the goldsmith's house in Estella. The following morning, Hilario Martija and Bernardino Jalón, the buyer of the silver, a merchant in Logroño, administrator of Don Luis de Múzquiz y Aldunate and of the Real Tabla in Viana and a future national militiaman, turned up at the aforementioned house. The price of the whole amounted to 11,895 reales fuertes.

In the legal proceedings carried out in 1814, Hilario Martija gave many excuses, leaving the ultimate responsibility to General Francisco Espoz y Mina, although the latter denied to the vicar of Igúzquiza that he had given those orders, limiting himself only to ascertaining the whereabouts of the relics. At one point, Martija declared that Espoz y Mina wanted to anticipate what the French would have done with the proceeds from the sale of the silver: provide for the troops' subsistence. In the end, pressed by the judge, he presented the receiptof 3 July 1813, signed by Espoz y Mina, which showed the submissionof the money received for the silver. The accounts of the Navarre Division, held by Melchor Ornat from Roncal, its treasurer, were even checked. This evidence led to Martija's first conviction being overturned. In his defence, he argued in mitigation that the urn had been sold for eight reales per ounce, a much higher price than the silver pieces sold from many churches.

Procession with the relics of Saint Veremundo in Villatuerta (8-III-2016) in the ark made in 1816, after the disappearance of the large silver urn in the War of Independence. Villatuerta had the relics for the five-year period 2013-2018. Photo: Montxo A. G., Diario de Navarra.

After the recovery of the relics of Saint Veremundo in 1814, both the majority of them deposited in the chapel of the Virgen del Puy in Estella, and those that had been distributed among those who had participated in their extraction from the old silver urn that contained them, were returned to the monastery of Irache in March 1815, with a large procession in which civil and ecclesiastical authorities took part, together with the guilds with their banners. The receptacle for the relics was a beech chest that Hilario Martija, the managerof the disposal of the silver one, ordered to be made, once he had located it in Igúzquiza.

Just the following year, around the same time, the abbot of the monastery of Irache proceeded to transfer them to a new urn of fine wood and bronze, in neoclassical style, crowned with scrolls and a dove, alluding to the great miracle of Saint Veremundo when he made a crowd of people be satiated during a very persistent famine.

Veremundo Arias y Tejeiro, a Benedictine monk, doctor of the University of Irache (1781), bishop of Pamplona until 1814 and archbishop of Valencia. From the latter city he wrote a letter on 28 March 1816, with some expressions that seem to prove his sponsorshipfor the new urn: "I am happy that the holy relics of my glorious saint have already been placed in his urn, although it is not as precious as the one he deserves..., I have done more than I could for my saint and if there is any little merit in it, he will know how to reward me superabundantly".

Of the subsequent history of the relics in their nineteenth-century ark, their transfers, openings and exchange quinquenal between Villatuerta and Arellano, we have news from different monographs, especially those published in 1899 and 1926 by Pedro Velasco y Martínez de Arellano, President of the seminar of Pamplona and Miguel Imas, parish priest of Arellano, respectively.

A first agreementbetween the two towns to share the relics was signed in 1821 on the occasion of the exclaustration of the monks during the constitutional triennium. In August 1821, the ecclesiastical and civil councils of Arellano and Villatuerta agreed on the distribution of the custody of the relics in a deed witnessed before the notary of Estella, Eusebio Ruiz de Galarreta. They fixed times, the presidency of the transfer processions, routes and all the details subject. Those from Villatuerta possessed the ark until 4th May 1822 and those from Arellano from that date until 24th September of the same year. From then on, the deadlinefor each village would be for three years. However, the return of the Benedictines to their monastery interrupted, for the time being, that exchange, by means of a solemn procession in which both towns joined together at the portal of San Agustín de Estella and went through the town to the sound of a general ringing of bells and the authorities of the town on the Ega River joined in. From Estella, the urn was taken to Irache with great apparatus.

The third departure, in this case final, of the monks in 1839 led to the transfer of the relics at first to Ayegui, although in November 1840 they were handed over to the Villatuerta monks. In the latter year, it was decided that the urn would remain in Villatuerta until April 1841 and in Arellano until September. From then on, the urn was to remain in each town for five years, with the transfers taking place on the 2nd of September, and this has been the case up to the present day, although the date was changed to the 3rd of the same month. Important dates in that shared cult were the celebration of the centenary of the death, with multitudinous festivities in Villatuerta in 1892 -following the Bolandos in 1092- and in Arellano in 1899 -according to the Irache Lectionary-, as well as the opening of the urn in the presence of the bishop in the aforementioned year, of which a certificatehas survived with all subjectof details. It should be noted that in 1899, according to the chronicles of the time, between 6,000 and 10,000 faithful gathered in Arellano for the opening and registration of the relics, with the parishes of Villatuerta, Muniain de la Solana, Aberin, Morentin, Allo, Lerín and Dicastillo, and processionally from the towns of Arróniz, Barbarin, Luquin, Urbiola, Villamayor, Azqueta and Igúzquiza.

Reliquary of Saint Veremundo in Villatuerta, by the silversmith Agustín de Herrera, 1640. Photo: Calle Mayor.

It is true that the relics of the saint remained in the monastery of Irache until the monks left finalin 1839. However, by then a significant part of them had already travelled to Villatuerta in the mid-17th century; subsequently, the silver arm of silver, which was destined for the veneration of the faithful in the monastery, went to Estella in the mid-19th century; and shortly before that, the bishop of Pamplona destined another part for Pamplona Cathedral. We will refer to the three examples preserved in different types of silverware.

The Benedictine community of Estella traditionally celebrated the saint's feast day with a sung mass and a solemn Te Deum, exposing the relic of the saint to public veneration during the octave in the old church of the monastic complex, erected thanks to the munificence of the Benedictine bishop Fray Prudencio de Sandoval.

The reliquary arm obeys a typology that is very common in Western and Hispanic silverware. It contains a thumb of the saint inside an oval with a gilded silver ring with a registrationthat reads: "+ BRAÇO DE SANT. BEREMVNDO 1612". It is very simple, its surface is decorated with C's and other stylised motifs on a dotted background. According to the datapublished by Pedro Velasco in 1899, it was a donation to the nuns by Father Caño, the last president of the exclaustrated community of Irache, who had acquired it after the death of the lay monk of Irache, Friar Juan Terrera, around 1850.

This was not the only relic kept by the nuns. Pedro Velasco reviewhimself kept another two; the first in a wooden reliquary arm, together with those of other saints, which the aforementioned fray Prudencio de Sandoval would have given as a gift. The relics it incorporates, all of them in silver teak, are inlaid along the sleeve of the arm dressed in the black Benedictine habit. The second, more interesting, was a "relic of the size and shape of a chestnut which, placed in a kind of silver censer with holes, serves to pass water to be administered to the sick". The latter is no longer in the monastery.

The parish of Villatuerta has preserved an exceptional piece, commissioned from the silversmith Agustín de Herrera at the end of December 1640, destined for two distinguished relics that the monastery of Irache gave to the parish, to applicationof the parish and the bishop of Pamplona, Juan Queipo de Llano, in January 1641. E. Ibáñez transcribed, in his monograph on Villatuerta, the two conference proceedingsrelated to the relics - specifically a jawbone and a rib - both that of extraction and that of the transfer to Villatuerta, dated 23rd and 30th January 1641. The reliquary is a beautiful piece of silver in its colour and consists of a large rectangular base with ornamentation of gadroons and the angles marked by C's and free pyramidal finials. The chest itself is mounted on the base, with cylindrical legs and a bulbous cover, topped by the statuette of Saint Veremundo.

Pamplona Cathedral holds another very elegant neoclassical reliquary, in silver and gilded silver, which was a gift from Bishop Joaquín Xavier Úriz y Lasaga (1815-1829) in September 1821. On the occasion of the suppression of the religious orders during the constitutional triennium, the objects of worship came under his jurisdiction, and he presented the cathedral with the distinguished relics of Saint Veremundo and Saints Nunilo and Alodia, from the monasteries of Irache and Leire, respectively. graduateThe bishop had attended the University of Irache in 1767, which may have influenced his decision to make the reliquary for the Benedictine saint. Although his wish would have been to take the set of relics of the aforementioned saints to Pamplona Cathedral, other circumstances obliged him to extract insignificant parts of them and set them in two pieces that he commissioned from Pedro Antonio Sasa, who punched both of them. Although the date mark has been incorrectly read as 1882, it actually reads 821, so the date is 1821, which is also consistent with the chronology of the bishop and the silversmith. Typologically, they have a circular base, a flared knot with garlands and a very high teakwood surrounded by silver rays in the same colour, the saints' being slightly higher than that of Saint Veremundo. The author of both pieces, Pedro Antonio Sasa (1745-1831), was very prolific, a native of Logroño who married in Pamplona a niece of Fernando de Yabar, with whom he had learned the official document. He was examined in August and October 1775 and his works can be found all over the region, being the author of several intaglio plates used for devotional prints and book illustrations.

Back of the chair corresponding to the monastery of Irache with the image of Saint Veremundo, in the chair of San Benito in Valladolid, 1525. National Sculpture Museum, Valladolid.

One of the most important images of Saint Veremundo in the Benedictine order, and particularly in the Congregation of Valladolid, is found on one of the backs of the famous high choir stalls of the monastery of San Benito in Valladolid, now in the National Sculpture Museum of Valladolid, where the relief of Saint Veremundo appears under the polychrome arms of the monastery in Navarre. This is the first surviving image of the saint outside Navarre.

positionThe aforementioned chairs were contracted in 1525 as a result of the extraordinary chapter of the Congregation in which it was decided that each monastery should buy a high chair and another leavefor 200 reales. At the time of the incorporation of Irache into the Castilian Congregation, Friar Álvaro de Aguilar (1525-1528), who was appointed to reform the house by the General of the Order, was in charge of its destiny. Among the artists who worked on it under the direction of Andrés de Nájera were Guillén de Holanda, who acted as carver, and Diego de Siloe, who carved some reliefs. Alonso de Toro (1523-1541), the same General of the Order who ordered in the General Chapter of 1535 "that the important works in the monasteries of our congregation that are to be done should not be done without informing our most reverend father of them, so that his reverence may go or send the people he sees fit to see them, draw them and make them equal, and so that they may be done in the manner of our congregation and as it suits him". The directivewas complied with in the following centuries, as can be seen in the documentation of Irache, in the licences to carry out works, such as the chapel of San Veremundo, which no longer exists.

The relief, simple and elegant, shows the Benedictine abbot in his cowl, with the hood over his head, revealing part of his tonsure, and holding a crosier and a book. It has no particular iconographic attribute and, as it is on the chair corresponding to the monastery of Irache, with its polychrome arms, it has been identified with Saint Veremundo, although it is true that the chronology of the piece is prior to the "fabrication" of the abbot as a saint.

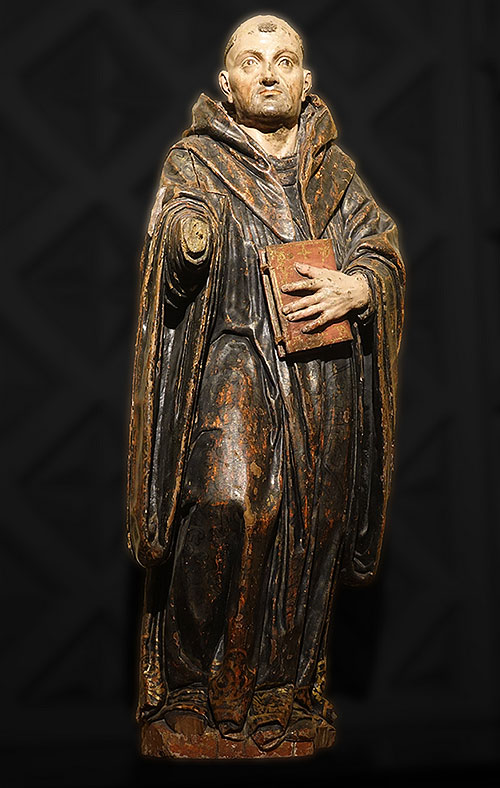

Saint Veremundo from the former main altarpiece of Irache, now in Pamplona Cathedral, the work of Juan III Imberto, 1613-1621.

As might be expected, it was in the monastery of Irache that notable sculptures were commissioned, some of which have survived to the present day, despite the disastrous consequences of the disentailment. It is not easy to identify the saint, as he is only recognisable as a Benedictine with his own black cowl and the abbot's insignia, with the crosier, mitre and pectoral. We can therefore conclude that there is no iconographic subjectof the saint, nor even any particular attributes that would help to identify him.

Leaving aside the relief of the Valladolid masonry to which we have already referred, it is worth mentioning, among the first documented images, in this case painted, the one made for the parish of Villatuerta by the painter Diego de Olite, which is reflected in the accounts for 1614-1616.

One of them, which formed part of the monumental altarpiece of the monastery of Irache, a work from the first third of the 17th century by Juan III Imberto (1613-1621), is now in the collection of the Diocesan Museum of Pamplona. Romanesque style prevails both in the mass and folding of the carving and, above all, in the face. It made a pendant with Saint Benedict and was replaced by Saints Emeterius and Celedonius. In the altarpiece of his former chapel, now in the parish church of Dicastillo, his figure is in the attic and now has a modelmore in keeping with the realism prevailing in the mid-17th century. It fits in perfectly with the chronology of the altarpiece, contracted at the end of 1655 and made in 1656 by the Estella assembler Gil de Iriarte, with the designof the monk Friar Esteban de Cervera.

In the two villages that dispute having been the birthplace of Saint Veremundo, Arellano and Villatuerta, there are also representations of the Benedictine saint from the centuries of the Baroque. In Arellano he has his own chapel with an altarpiece from around 1660, a large sculpture and the image of the saint in relief on the door of the tabernacle with the enormous dove on his head, which alludes to the famous miracle. In the Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Loveof the Virgin of Uncizu in the same town there is a sculpture of him from the mid-17th century, in this case with a book and a crozier. In the parish church of Grocin, in an altarpiece from the first decades of the 17th century, we also find a sculpture earlier than the one in Uncizu de Arellano, with a markedly Romanesque character and the crozier and book, which could lead us to think that it is, in reality, Saint Benedict.

The stone image on the façade of the monastery of Irache, with its large crozier and the long sleeves of its monastic cowl, should be dated to the beginning of the 18th century. It is an archaic piece for its time due to its lack of movement and frontality, although it is effective for the place it occupies.

At the end of the 19th century, various images of the saint arrived from the Olot workshops, including the one that the Piarists placed for worship in the chapel of the saint in Irache, after their establishment in the monastery in 1895. By then, the prior of El Puy, José María Arrastia, had commissioned another for the aforementioned sanctuary in 1876, in whose honour he published a novena, illustrated with a small woodcut, in 1879.

At plenary session of the Executive Councilin the 20th century we should highlight the marble image of the saint, as a mitred abbot, with open book and crozier, destined for the new altarpiece-altarpiece of Pamplona Cathedral in 1946, as well as the one at chapelin the Palacio foral. The latter appeared on its neo-Gothic altarpiece together with the co-patrons of the Kingdom, Saint Fermin and Saint Francis Xavier, and the Immaculate Conception. The whole ensemble, which disappeared in 1932, also belonged to the neo-Gothic aesthetic and the images were linked to the forms of the Olot workshops, all dating from the beginning of the 20th century. fileThe sculpture of Saint Veremundo was later moved to the chapel of the Maternidad and was later ceded to the parish church of Arellano, although its photograph, which appeared in one of the issues of La Avalancha ( 24 May 1935) and is kept in the Photo Library of the Municipal Museum of Pamplona, has now been lost, although not its photograph, which appeared illustrating one of the issues of La Avalancha ( 24 May 1935) and is kept in the Photo Library of the Municipal Museum of Pamplona. The five sculptures together with their altarpiece were valued in a general inventory of the palace at 5,000 pesetas in 1925.

In Villatuerta, there is the only commemorative monument built in his honour in 1999. It was made on the initiative of the local brotherhood of the saint, with the surgeon Juan Luis Castiella Iribas serving as model. It was made by the sculptor Juan Chivite in stone and in an attitude of blessing, accompanied by his crosier and the abbot's mitre at his feet. modelSubsequently, in March 2010, it was replaced by another bronze one, following the same style as the previous one, made in the workshops of José Ángel Veremundo San Martín, a sculptor from Villatuerta, in Vitoria.

As far as intaglio prints of his image are concerned, apart from the large engraving with his wundervita of 1746, we should mention the illustration that accompanies his hagiography, published in Pamplona in 1764, which is accompanied by the print of the saint in Benedictine habit, with crosier and mitre at his feet, by the Aragonese José Lamarca.

Renaissance casket of the relics of Saint Veremundo, 1584.

Its construction was due to the wishes of the abbot Antonio de Comontes, who was the abbot of Irache between 1583 and 1586. He was an outstanding entrepreneur, especially in his two periods at the head of San Martín Pinario in Santiago de Compostela, where he began the new work on the church in 1590. Grateful to the saint for the health he had regained after a serious illness, he ordered the construction of the ark of relics, which was a veritable votive offering, although it was paid for out of the monastery's sacristy expenses, not in 1583, as is often repeated, but the following year. We should not forget the post-Tridentine context and the example of Philip II at the Escorial regarding the cult of relics. It should be remembered that between 1574 and 1598 countless relics arrived from many parts of Spain, and above all from Germany, to prevent their desecration.

This singular piece, B, was attributed by Biurrun to the sculptor Pedro de Troas and this fact has been repeated time and again, although those who actually made it were a sculptor named Francisco - probably Francisco de Iciz - who worked on it with his servant for fifty-one days, Master Martín de Morgota, who worked on it for seventeen days, and Pedro de Gabiria for twenty-five days, for which they were paid in December 1584 and June of the following year. Pedro de Troas made some figures of angels and an Infant Jesus for the lid that have not been preserved, and the polychromy of the whole was done by the prestigious Juan de Frías Salazar at position. We only know for certain that Francisco de Iciz took part in the auction of the altarpiece of San Juan de Estella in 1563. If the sculpture of the reliefs is rich, the polychromy by Miguel de Salazar is no less so.

The reliefs on their faces narrate as many miraculous passages from the life of the saint, of the many that were attributed to him.

In the two scenes that make up the main front, the miracle of the dove is narrated, with the saint celebrating in one and the crowd with the dove in the other. We will refer to this miracle in detail when we deal with the same scene in the Villatuerta altarpiece. On the other main front we find two other compartments dedicated to narrating various healings of the blind and crippled and their death. In 1610, the chronicler Fray Antonio de Yepes refers briefly to his gifts as a thaumaturge with these words taken from the matins lesson of the saint's official documentin his monastery: "Saint Veremundo shone with the gift of working miracles, and that he expelled demons from men's bodies, and that he gave sight to the blind and healed different illnesses". The passage of his death with the saint on his bed and the monks accompanying him is recreated with the old medieval formula whereby at the moment of his last breath his soul, in the form of a naked creature, is gathered up by angels in a halo of glory.

On one of the side fronts the saint is depicted whipping a picturesque naked demon with rods and on the other at the moment of receiving three crowns from the hands of the angels in glory, alluding to the three virtues of charity, penance and prayer that he practised in his life. The cover contains two small reliefs of Saint Martin parting his cloak with the poor, in parallel with the charity of Saint Veremundo, and a holy knight and matamoros, possibly Saint Millán de la Cogolla, the head of a monastery with close links to Irache. The other two scenes show the saint saving a man about to drown in a great storm and saving the monastery's crops. Both events also have their correspondence in the texts of the Lectionary, mainly, which were copied by his biographers. As for the story of the man who almost drowned, the literary sourcestates: "The river Ega, which flows through the town of Estella, had risen exorbitantly, and a poor man was unexpectedly swept away by the waters, and was in danger of perishing in them. In such a grave conflict he invoked the saintly Abbot Veremundo, calling him to his aid, and at once he was free from danger and out of the impetuous current". The Lectionary and the hagiographies of the saint also relate the content of the second scene as follows: "On another occasion, some men of bad life set fire to the monastery's harvest threshing floor. When the holy abbot was warned, he began to pray, and the fire suddenly ceased".

It can be deduced that the sculptor took good gradefrom the monks of Irache themselves, great connoisseurs of the life of their holy abbot, as well as from the Lectionary of 1547, which is the oldest written text with news of his life, although at that time there may also have been other written sources.

When the work was completed, the relics of Saint Veremundo were transferred to its interior in a very solemn celebration, with a large number of people adoring the venerable remains. Some sources state that the skull was placed in a silver urn, something that neither the documentation of the time nor later documentation teststates. The reliquary arm was indeed a reality and today it is preserved in the Benedictine Sisters of Estella, where it ended up in the mid-19th century, as we will see later on.

In July 1613 the monks contracted an altarpiece so that the ark could be placed with greater dignity "in the arch of the church, where the sepulchre is, in front of the door of Wayside Cross". It was commissioned to Juan III Imberto for the sum of 80 ducats and deadlineto be completed by All Saints of the same year.

Relief of the miracle of Saint Veremundo in the main altarpiece of Villatuerta, 1643 and 1645, Pedro Izquierdo and Juan Imberto III. Photo: Main Street.

The main altarpiece of Villatuerta has two very interesting reliefs in the side streets of the first section: the first alluding to the battle of Navas de Tolosa, the only one of its kind in Navarre, and the second with the miracle of the dove of Saint Veremundo, which we are going to refer to. positionThe altarpiece was commissioned by Bishop Juan Queipo de Llano in 1640 and in the following years, between 1643 and 1645, Pedro Izquierdo and Juan Imberto III were commissioned to build it on the condition that it be done with the modelof that of the Franciscans of Estella, a work that no longer exists. Its polychromy was carried out by Miguel de Ibiricu and Juan Ibáñez in the mid-17th century.

Due to its spectacular nature, topic was widely disseminated in liturgical and hagiographic texts, sermons and iconography, including one of the reliefs in the 1584 reliquary-chest and one of the vignettes in the 1746 engraving, the work of Friar José de San Juan de la Cruz. It was undoubtedly the passage of his life with the greatest iconographic fortune. It is not surprising that it was chosen for the Villatuerta altarpiece, in the context of the arrival of the saint's relic from Irache in 1641, barely two years before the work was contracted. The prodigy is recounted in detail in the main hagiographical texts by Father Yepes, the Bolandos and Fray Miguel Soto. It seems that they all took it from the monastic Lectionary of 1547, the text of which he translated from Latin as follows:

It happened at that time that a cruel famine destroyed the whole kingdom of Navarre, so that many, compelled by so great a calamity, came to the holy man to beg for alms; and as the famine grew worse every hour, one day there came to be three thousand men. issue; But as there was not enough food in the house to feed so great a crowd, because the servants who had gone out of the province to fetch food on the holy abbot's orders had not returned, there was a great clamour and uproar among those present; for as they were so famished, they had not the strength to go anywhere else... When the saint saw this wretched spectacle, he went to the altar to say mass with Bfeeling: a wonderful thing! When he had reached that place, where the priest prays to God for the people, as St. Veremundo prayed to God for help with many tears, a white dove came down from heaven, and fluttered over the heads of each one, almost as if it wanted to touch them, and then went up to heaven in the sight of all: After this, each of those who were present felt that he had eaten his fill, and each one was as satisfied as if he had eaten a splendid and varied meal; for man does not live by bread alone, but by the word that proceeds from the mouth of God. So they all gave thanks to the Lord together with St. Veremundo and returned to their homes.

The relief, faithful to its textual source, sample, shows the saint celebrating mass, with his back turned, before a canopied altar and curtains gathered on either side, at the precise moment of raising the Sacred Form, in the presence of several tonsured monks of different ages with their cowls and a couple of figures - one bearded and the other beardless, They are all in awe of the prodigy that takes place, not only with the radiance around the Eucharist, but also with the appearance of the dove that appears in the upper right part of the composition, among the clouds. The polychromy of the composition is particularly noteworthy, especially the side bands of the saint's chasuble with delicate bouquets.

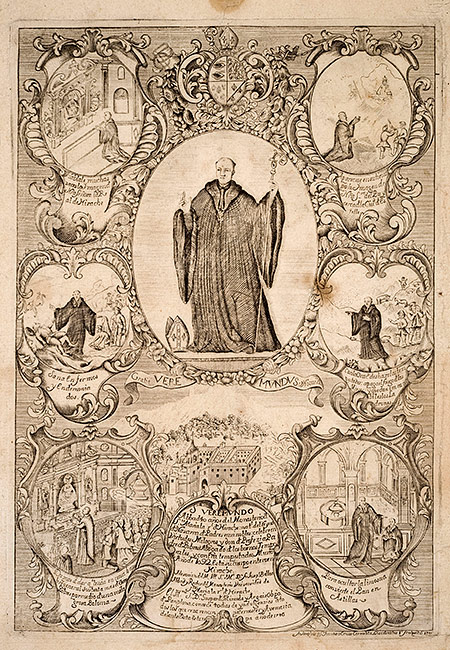

Engraving with scenes from the life of Saint Veremundo by the Carmelite friar José de San Juan de la Cruz, 1746.

A very unique engraving, made by the discalced Carmelite friar José de San Juan de la Cruz, is dated 1746, shortly after the cult of Saint Veremundo was extended to the whole bishopric of Pamplona.

Its typology is typical of a wundervita, or admirable life, due to the representation of various prodigies of the protagonist in the ensemble. The events narrated in the vignettes have their literary correspondence with the texts that had previously been written about Saint Veremundo. It is a veritable hagiography on paper. Some of these passages were already in the Renaissance chest.

The composition presents an oval with the figure of the saint in his usual iconography under the monastery's coat of arms, four vignettes around him and in the lower third a large registrationwith another two vignettes on either side. The upper left-hand vignette shows the saint in prayer before a Baroque altar with vegetal finials, presided over by the titular image of the monastery, the Virgin of Irache.

The upper right scene depicts the apparition of the Virgin of El Puy. The relationship between the Abbot of Irache and the image of El Puy, a true sign of the identity of Estella and its lands, was very useful for spreading the devotion and popularity of Saint Veremundo. Those who wrote about the legend of that Marian image as early as the 17th century, such as Francisco Eguía y Beaumont, argued that it was contemporary with the saintly abbot of Irache.

The central left-hand vignette shows the saint freeing a demoniac and helping the needy and crippled who approach him. The chronicler Fray Antonio de Yepes refers briefly to this Schoolof the saint in 1610 with these words: "he expelled demons from the bodies of men, and that he gave sight to the blind and healed different illnesses".

In the central right-hand scene we find him in a country passage next to the harvest, protecting it from the clouds and some immobilised figures. Miguel Soto refers to these prodigies, specifying some of them, such as that of a man who saved himself in a flood of the river Ega by invoking the saint, or that of the men of bad life who set fire to the monastery's crops, the criminals remaining immobile after the abbot's intervention, being able to walk alone towards the monastery, where they asked the saint for forgiveness. With regard to storms, the intervention of the saint's relics is documented during cloudy weather at the beginning of the 17th century, in 1614, when several witnesses stated that "when the relics are taken out because of a storm that throws stones, they immediately turn to water and then the storm ceases". The lower left-hand vignette narrates the miracle of the dove inside the abbey church, to which we have already referred.

The last of the representations located in the lower left vignette narrates another scene of his life. He appears on his knees showing his abbot the bread he was carrying for the needy, turned into wood chips. This fact is echoed in hagiographic texts and is a topic that presents parallels with passages from the lives of such popular saints as Saint Diego Alcalá or Saint Elizabeth of Hungary.

The promoter of the printing press was Father José Balboa (1688-1771), abbot of Irache between 1745 and 1749, and general of the Benedictine order between 1757 and 1761. From the latter post, he determined the distribution of teaching posts among the most deserving subjects, the strict observance of the rule, as well as study and reading in order to raise the cultural level of the monks.

The author of the intaglio was a multifaceted Discalced Carmelite friar, active as a designer of architectural works and altarpieces in Navarre in the second half of the 18th century. Born in Logroño in 1714, his name was José de Ágreda y Ruiz de Alda, he was professed in Corella in 1734 and lived in several convents in the Carmelite province, especially in the capital of La Rioja, where he died in 1794. His work as an engraver in other provinces, such as Soria and Logroño, has been studied and vindicated by René Payo and José Matesanz on the basis of some prints in the Antonio Correa Collection, which depict Saint Saturio and Saint John of the Cross, and one of the Virgin of La Soledad de la Merced in Logroño.

fileGeneral of Navarre. Monastery of Irache

Notarial Protocols

Processes

Kingdom

Ecclesiastical business

fileDiocese of Pamplona

filePamplona Municipal Council. Photo library

fileof the Basilica of El Puy in Estella

certificateSanctorum quotquot toto orbe coluntur, vel a catholicis scriptoribus celebrantur, quae ex Latinis & Graecis, aliarumque gentium antiquis monumentis / collegit, digessit, notis illustravit Joannes Bollandus; operam et studium contulit Godefridus Henschenius...Martii, tome I, Antuerpiae, Iacobum Meurisium, 1668, pp. 794-798. Reprint, Brussels, Culture et Civilisation, 1966, pp. 794-798.

ARRASTIA, J. M., Novena histórica y deprecativa del glorioso San Veremundo Abad del célebre Monasterio de Hirache: seguidas de otras novenas de varios santos, Pamplona, Imprenta y Litografía de Sisto Díaz de Espada, 1879.

ARRÚE UGARTE, B., "Nuevas firmas e inscripciones de artistas aparecidas durante la restauración de la iglesia del Monasterio de San Millán de la Cogolla de Yuso (La Rioja)", El Greco en su IV Centenario: patrimonio hispánico y diálogo intercultural, Toledo, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, 2016, pp. 855-869.

BIURRUN Y SOTIL, T., La escultura religiosa y bellas artes en Navarra durante la época del Renacimiento, Pamplona, Gráficas Bescansa, 1935.

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., "Iconografía moderna de los bienaventurados", Signos de identidad histórica para Navarra, vol. II., Pamplona, Caja de Ahorros de Navarra, 1996, pp. 169-182.

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., Imagen y mentalidad. Los siglos del Barroco y la estampa devocional en Navarra, Madrid, Fundación Ramón Areces, 2017.

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., Versos e imágenes. Gozos en Navarra y en una colección de Cascante, Pamplona, University of Navarra-Fundación Fuentes Dutor-Vicus, 2019.

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., "Patrimonio e identidad (28). Un relato novelesco: las reliquias de san Veremundo en la Guerra de la Independencia", Diario de Navarra, 6 March 2020, pp. 72-73.

GOÑI GAZTAMBIDE, J., Historia de los obispos de Pamplona. S. XVIII, vol. VII, Pamplona, Government of Navarre-Eunsa, 1989.

IBÁÑEZ, E., Esbozo histórico de la villa y parroquia de Villatuerta, Pamplona, Imprenta de Capuchinos, 1930.

IBARRA, J., Historia del monasterio benedictino y de la Universidad literaria de Irache, Pamplona, Talleres Tipográficos "La Acción Social", 1938.

IMAS, M., Glorias navarras. San Veremundo de Irache, Pamplona, Imp. Viuda de Ricardo García, 1926.

MAÑERU SANZ DE GALDEANO, L., Villatuerta, nuestro pueblo, Villatuerta, El Callejón, 2012.

MARCELLÁN, J. A., El clero navarro en la Guerra de la Independencia, Pamplona, Eunsa, 1992.

MIGUÉLIZ, I., "Pérdidas de alhajas de la iglesia durante la Guerra de la Independencia (1808-1814)", Príncipe de Viana, n.º 256 (2012), pp. 731-759.

Nueva novena en obsequio del incomparable Abad de Irache el glorioso San Veremundo, por los R.R. P.P. Escolapios de Ntra. Sra. La Real de Irache, Estella, Imprenta de Eloy Hugalde, 1895.

PAYO HERNANZ, R. and MATESANZ DEL BARRIO, J., "Una polémica artística en el entorno de la Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. Fray José de San Juan de la Cruz and José Bejes. Entre el Barroco Castizo y el Barroco Cortesano", De Arte, no. 10 (2011), pp. 129-156.

PELLEJERO SOTERAS, C., "El claustro de Irache", Príncipe de Viana, no. 5 (1941), pp. 16-35.

SAGASTI LACALLE, M. J., "Retablos laterales del monasterio de Irache en Dicastillo", Príncipe de Viana, no. 219 (2000), pp. 21-46.

SAGASTI LACALLE, M. J., "Arquitectura del Seiscientos en el Monasterio de Irache", Ondare, no. 19 (2000), pp. 314-323.

SOTO SANDOVAL, M., Vida de el Glorioso S. Veremundo, monge y Abad de Hirache, Pamplona, Herederos de Martínez, 1764.

SOTO SALDOVAL, M., Vida de el glorioso San Veremundo, monge de Hirache: sacada de los papeles de su file..., Pamplona, Joaquín Domingo, 1788.

SOTO SANDOVAL, M., Vida del Glorioso San Veremundo, monje y abad de Irache, Pamplona, Imprenta Provincial, 1899, 3rd edition enlarged with an interesting reportof the transfers of the relics and their cult arranged by P. V. and M. de A. (Pedro Velasco).

YEPES, A., Coronica General de la Orden de San Benito Patriarca de Religiosos, vol. III, Universidad de Irache, Nicolás de Asiayn, 1610.

ZARAGOZA PASCUAL, E., "La sillería del monasterio de San Benito de Valladolid", Revista Nova et Vetera (1985), pp. 151-180.

ZARAGOZA PASCUAL, E., "Artistas benedictinos vallisoletanos (siglos XV-XIX)", report ecclesiae, n.º 16 (2000), pp. 327-342.