Photographs of the Catalog Monumental y Artístico de la Provincia de Navarra (1916) by Cristóbal de Castro.

PILAR ANDUEZA UNANUA

UNIVERSITY OF LA RIOJA

1.-Inventories and catalogues

The State's awareness of the need to protect the historical and artistic heritage was born in 18th century France as a result of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution. Catalogues and inventories were soon seen as an effective tool and an essential means for the knowledge and protection of monuments. This became clear as early as 1793 when Instructions were sent to all Departments in the country on how to inventory and conserve, throughout the Republic, all objects that could be of use to the arts, sciences and the Education. A few years later, Ludovic Vitet, as Inspector General of Historical Monuments, travelled around the country taking good grade of the monuments and inventoried them for their conservation. In addition to this work, restoration work was also carried out under the auspices of his successor, Prosper Mérimée, and managed by the Commission des Monuments Historiques, created in 1837.

In eighteenth-century Bourbon Spain, the Royal Academy of History and the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando took the initiative for the development of some rules that tried to protect, for the time being very partially, the heritage. The demolishing disentailment process of the nineteenth century served as a fuse to create a technical and legal apparatus, both state and provincial. And so, following the French path, the Central Commission of Monuments and the Provincial Commissions were born in 1844. Among their main purposes was to "acquire news of all the buildings, monuments and antiquities that exist in their respective provinces and deserve to be preserved", as well as "to form catalogs, descriptions and drawings of the monuments and antiquities". With this, the relevance of inventories and catalogs was emphasized. The results were not the expected ones, so that a new royal decree dated June 1, 1900 ordered the elaboration of an ArtisticCatalog of Spain, with which would be obtained "the complete and orderly cataloguing of the historical or artistic wealth of the nation". The systematic and complete registry of the country's assets would be made province by province. The work to develop the Catalog Monumental de España was entrusted to the art historian Manuel Gómez Moreno who, between 1901 and 1907, carried out the Catalog corresponding to Avila, Salamanca, Zamora and León. The desire to obtain quick overall results meant that those responsible extended the commission to other authors, not always with adequate preparation, which led to very different criteria and results, unequal and even unfinished parts. It is in this context that we must situate the Catalog Monumental y Artístico de la Provincia de Navarra, carried out by Cristóbal de Castro.

Cristobal de Castro

Cristóbal de Castro was born in Iznájar (Córdoba) on 22 November 1874. Although he studied law at university, his working life was centred on journalism and literature, with Andalusian customs and women's themes. He was a member of the Royal Academy of Sciences, Fine Arts and Noble Arts of Cordoba and of the Hispano-American Academy of Cadiz.

His relationship with the Catalog Monumental de España began on February 1, 1912, when he requested to make the part corresponding to the province of Alava. Once his request was accepted, his cataloguing work began in the Basque province, to be followed by the catalogs corresponding to Orense (1914), Logroño (1915), Navarra (1916), Santander (1917-18), Cuenca (ca. 1920) and the Canary Islands (1921).

Photo 1. Cristóbal de Castro

Undoubtedly, Cristóbal de Castro lacked the appropriate training to undertake such an arduous and specialized task. In the words of Amelia López-Yarto, we find ourselves before the "most inept" author of all those who participated in that vast project initiated in 1900. In fact, since the publication of the Catalog de Álava in 1915, the poverty of his results has been proven, and since then there has been no lack of criticism of his work from specialized voices, such as Elías Tormo, Leopoldo Torres Balbás or, decades later, Gaya Nuño.

3.-The Monumental and Artistic Catalog of the Province of Navarra

Although in 1909 the historian, Arabist, archaeologist and numismatist Antonio Vives asked to execute the Catalog of Navarra, after having finished that of the Balearic Islands, the task officially fell to Cristóbal de Castro, according to the royal order of March 1, 1916. He was to carry it out in a period of eight months and would be paid 800 pesetas. After apply for an extension of four months, he finally delivered the commission and in March 1918 the Commission issued a very favorable report . There is no doubt that whoever wrote this report had not read Castro's work very carefully or was unfamiliar with the monumental heritage of Navarre, since the Catalog is clearly poor, fragmentary, partial and with significant deficiencies and errors, especially if we compare it with the works of some other provinces.

The Catalog Monumental y Artístico de Navarra consists of five volumes (33 cm.), bound in leather, of which two are texts and three are photographs (419).

Photo 2. Cover of the Catalog Monumental y Artístico de la Provincia de Navarra. Volume 1. Text

(Photo: Ministry of Culture. high school de Patrimonio Cultural de España)

Photo 3. Cover of Catalog Monumental y Artístico de la Provincia de Navarra. Volume 1. Photographs

(Photo: Ministry of Culture. high school de Patrimonio Cultural de España)

Castro structured his work in two parts. In the first, in addition to an extensive introduction, he devoted four chapters to the history of Navarre up to the Modern Age. In the second part, he focused on the monumental heritage, starting in Pamplona, and in the second volume he went on to catalogue the rest of Navarre by dividing it into judicial districts: Pamplona, Aoiz, Estella, Tafalla and Tudela.

Although its goal was to "briefly study the epochs and their archaeological periods in a synthetic manner, in order to then, in what should properly be called an inventory, proceed to the cataloguing of each monument, with the extension required by its importance", the result did not respond to these principles.

Photo 4. Catalog Monumental y Artístico de la Provincia de Navarra. Volume 1. Text (Photograph: Ministry of Culture. Institute of Cultural Heritage of Spain)

After analyzing its approach, texts and photographs, it can be affirmed that the Catalog was totally incomplete and insufficient in terms of cataloguing, leaving significant real estate properties uncollected and barely alluding to some movable properties. At the same time, the author revealed important gaps in the knowledge, both in specialized language and in artistic styles. The reading of the work also denotes a nineteenth-century vision focused on medieval monuments, overlooking other styles such as Renaissance and Baroque. And the same happens with religious architecture, which floods everything, as opposed to civil architecture, especially domestic and even military architecture, to which he barely alludes.

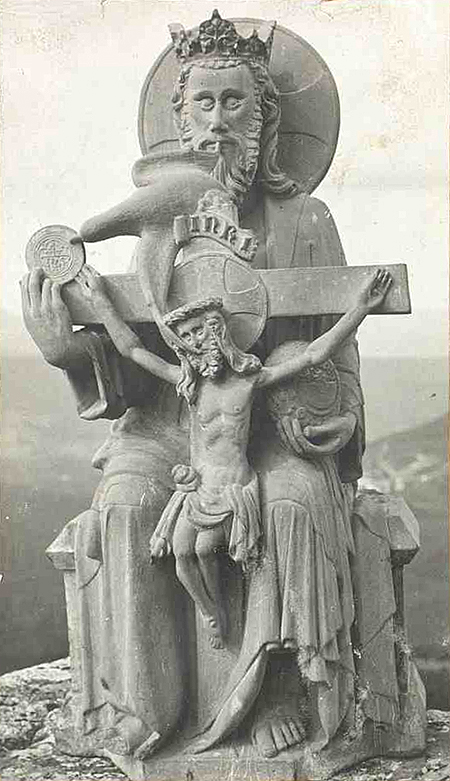

4.-The photographs of Catalog Monumental

The photographic documentation provided in the three volumes of this Catalog is the most relevant part of the work. It focuses mainly on the exterior of significant medieval buildings, although it also includes bridges quite profusely, while domestic architecture is very scarce. Movable goods also have a testimonial presence: archaeological pieces, some paintings and sculptures, silver objects, ornaments or stained glass appear in its pages in a very punctual way and without a clear justification.

Photo 5. "Cloister of San Pedro de la Ruá (sic)". Catalog Monumental and Artistic of the Province of Navarre. Volume II. Photographs (Photograph: Ministry of Culture. Institute of Cultural Heritage of Spain)

Photo 6. "Gulina Valley. La Trinidad de Aguinega (sic)". Catalog Monumental and Artistic of the Province of Navarre. Volume II. Photographs (Photograph: Ministry of Culture. Institute of Cultural Heritage of Spain)

Leaving aside the artistic and historical values of these photographs, this subject of documentation is crucial today for the knowledge of heritage. These images are visual records that allow us to perceive with absolute fidelity the state in which some cultural assets were in the first decades of the 20th century and thus to verify the subsequent evolution they have undergone. They also give us the possibility of learning about the ravages caused by the disentailments of the 19th century, and even of analysing the restoration criteria that were subsequently followed.

Many of the photographs on Catalog were provided by Julio Altadill, vice-president of the Monuments Commission of Navarre, and by the organization itself. To this were added those taken by the photographer Miguel España and those acquired from local photographers. Nevertheless, there is a total disproportionality in the presentation that the author makes of the photographs, offering some localities and/or buildings with multiple photographs and others, on the contrary, with a single copy or even without any photographic reflection.

Of the 419 photographs of Catalog, we present below a small selection that, for various reasons, seem to us to be significant. The wording we have given them corresponds strictly to the caption of the photograph that appears in handwritten or typed form on each copy. Some of these identifications made by Castro are erroneous and there is no lack of inaccuracies and misspellings in the names of some localities and works.