The Glass Rosary of Saragossa under the gaze of a visitor from Navarre in 1897

EDUARDO MORALES SOLCHAGA

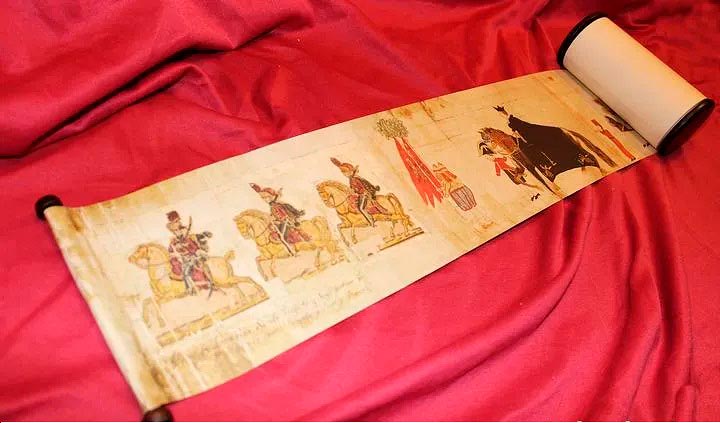

In a private collection in Pamplona there is a watercolour in the form of a scroll depicting in minute detail the procession of the Crystal Rosary in Saragossa in 1897. The painting, which is linear in nature, is structured around two stems that allow the viewer to advance along the procession, making it a sort of 19th-century souvenir.

It is housed inside a pretty cardboard box made to measure, painted as if it were brown leather, also incorporating small screws painted on the lid, which also has a decorative and sinuous green cartouche, where the degree scroll that identifies the composition appears: "Procesión del Rosario del Pilar de Zaragoza. 13 October 1897".

Roll of the Crystal Rosary (a) and its cover (b).

The roll reaches the not inconsiderable length of 11 metres and 32 centimetres. As for its height, it is not entirely regular, but at average it is more than 7.5 cm. On such a large surface, the author depicts, according to his own accounts, 1,800 figures. As far as the process is concerned, there are still traces of the pencil sketches, which were later transferred to pen and watercoloured with mastery and taste.

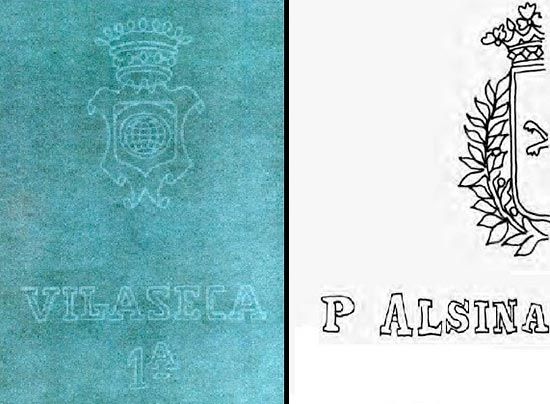

The watercolour is made up of the union of fragments of sized, moderately regular (30 cm in most cases) thread paper, on which the watermarks of two paper manufacturers have been found: on the one hand, those of the first class of José Vilaseca y Doménech, a Catalan businessman who not only continued the family tradition in the Capellades factory (Barcelona), but also industrialised the production process, which led to an economic and commercial expansion B ; on the other hand, Pedro Alsina y Dalmau († 9 December 1919), an Aragonese businessman who had two paper mills in Villanueva de Gallego, awarded two medals of first prize class in the Aragonese exhibition of 1885-1886. The presence of an Aragonese paper reaffirms the idea that it was made in Zaragoza.

Paper marks: José Vilaseca and Pedro Alsina.

The purpose of this virtual exhibition , apart from making this marvellous example of Navarre's heritage known, is to analyse the format used in the watercolour, the historical context of the procession, the institutions and artistic assets represented and, finally, its authorship. As with other similar scrolls on the peninsular, such as the Corpus Christi in Valencia - of which a brief outline is given - a more extensive publication would be desirable than this virtual exhibition , accompanied by a facsimile edition of the watercolour.

A substantial difference between Western and Eastern painting is the format, the former being intended to hang on walls permanently and the latter to be seen only occasionally and, at most, by a couple of observers.

It is in this sense that the hand scroll tradition, which goes back a long way, fits in. It has an elongated, narrow format (up to 40 cm high and several metres long) and is usually depicted on paper, with scenes, texts or a combination of both, which are progressed by the twisting of two wooden rotators. Often wrapped in silk, they are preserved in wooden boxes that identify them and sometimes turn out to be true works of art. Many of the most prestigious museums of decorative arts have decorated scrolls in their collections.

Although all indications are that the format originated in East Asia, some research links it to India in the 4th century BC, while others place its origins in the Chinese Spring and Autumn period (771-476 BC). However, silk or paper was not used as a medium until the 1st century and painted scenes were not depicted until the 3rd century. Five centuries later, they were introduced into Japan by Buddhism, where they are known as emakimonos.

In any case, and in those latitudes, they were considered luxury objects and were made by the most skilful masters based in their respective imperial courts. In terms of iconography, in the case of China, landscape scenes stand out as a percentage, such as the panoramic view of "The Qingming Festival by the River" (Zhang Zeduan, 12th century), while in Japan, scrolls with historical scenes are more frequent, such as those of the "Heiji monogatari" (13th century), which described the Heiji rebellion in ten scrolls - three of which have survived. The most interesting is the one in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Heiji Rebellion Scroll (13th century).

In Europe, meanwhile, similar media were not used to show narrative continuity in the compositions, but rather overlapping events in the same shot, playing with risky and unnatural perspectives, or using vignettes or recorded series for each of the scenes that made up the story in question.

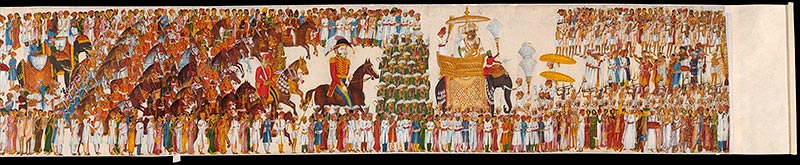

The territorial expansion of European nations, probably in the transition between the 18th and 19th centuries, meant that this curious oriental format permeated well into the 20th century in the West, adapting to traditional iconography, including both civil and religious solemnities and panoramic views of cities, everyday subjects, uses, customs and banalities. This fusion probably took place in British India, as is shown by very early scrolls, which coincide with the military rule of the colony, among which the "Scroll of the procession in honour of Shiva organised by Krishnaraja Wadiyar, Raja of Mysore" (1860), in the Victoria and Albert Museum, stands out for its length and detail.

Scroll of the procession in honour of Shiva organised by Krishnaraja Wadiyar, Raja of Mysore. Fragment (1860).

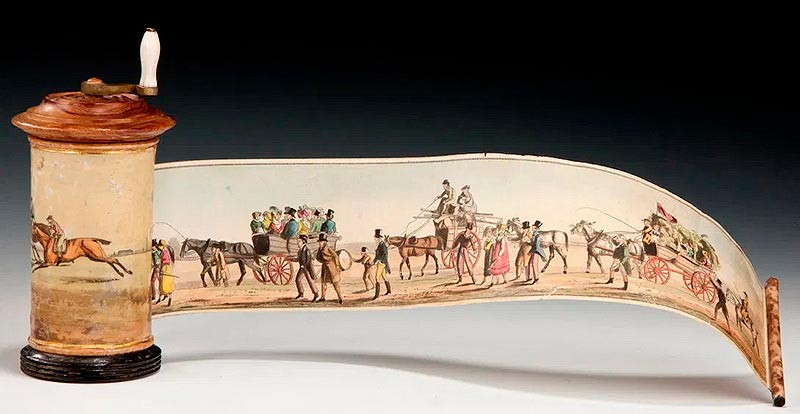

It was in England, therefore, that the roll format became widespread in the early 19th century, with the involvement of printers, publishers and lithographers, such as Thomas Alken, Robert Dale, Robert Cruikshank, Robert Havell and Thomas Rowlandson. Preserved are views of cities (London or Brighton-1822/1833), river courses ("Panoramic view of the Thames, from Richmond to Westminster", 1829), customs (horse racing, fox hunting, boxing, fashion...), royal solemnities (coronations of George IV and Queen Victoria, 1822/1838), among many others. As a curiosity, the collection of Major John Roland Abbey contains almost two hundred panoramas, although not all of them are in roll format.

Going to Epsom Races (London, 1819)

Panorama of a Fox Hunt (London, 1828).

Coronation of George IV (London, 1822).

They were sold either finished, with the lithographs watercoloured, cut out, glued and crimped on the roll, or on sheets of paper, exempt from the process and much cheaper, so that the buyer could act as an artist. There are even examples from the 20th century, such as the coronation of George VI in 1937. In any case, although the roll format prevailed, portfolios with individual lithographs continued to be printed, such as the one for the funeral of the Duke of Wellington (1852), and more complicated devices also appeared, such as the myriopticon, a box decorated with a framework in which the roll was mounted and which acted as a small theatre. The first one on record is the satirical "A Journey to London" (1823), and it quickly became widespread with themes from all over subject, including sacred history. Even some booksellers and bookbinders, such as Sangorski and Sutcliff, built custom boxes in this style for pre-existing scrolls in the 20th century.

Civil War Myriopticon. Exterior (Springfield, 1866).

Civil War Myriopticon. Interior (Springfield, 1866).

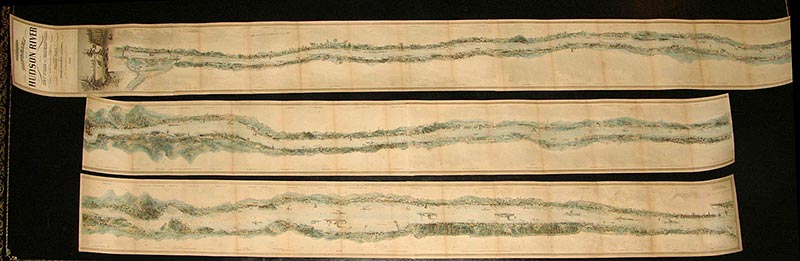

The genre also came to the United States in its simpler structure, such as the "Panorama of the Hudson River from New York to Waterford" (1847), and in its more complicated format, such as the myriopticons of the Civil War and Father Christmas (1866), and that of the World's Columbian exhibition of Chicago (1892). Outside the Anglo-Saxon world, the scroll format did not crystallise in other European nations, with the exception of exceptional cases such as "The Solemn Procession of Corpus Domini" in Rome, published in early 1839. In any case, connected scenes were generally published, albeit physically isolated in bindings and albums, as for example a luxurious publication with the "Procession of Saint Macarius of Ghent" (1867).

Panorama of the Hudson River from New York to Waterford (New York, 1847).

La Solenne Processione del Corpus Domini. Fragment (Rome, 1839).

In the case of Spain, narrative descriptions were made in traditional format, except for many examples preserved in Catalonia known as fulls de rengle, printed in popular culture with the representation in rows of processions, parades and entourages, which have their origin in the so-called aucas or aleluyas. Examples of woodcuts dating back to the 18th century have been preserved, which were later adapted to the new lithographic printing techniques used in prestigious establishments such as the Paluzié house in Barcelona and the Grau family in Reus. The rows, many examples of which are preserved in archives such as that of Joan Amades, could be cut out and glued into a single strip, giving rise to a tradition similar to the English one, as in the case of the scroll of the "Corpus Christi Procession in Barcelona" preserved in the city's Historical Archive file . In Valencia, woodcut aucas of religious processions were also published throughout the 19th century. Outside Levante, however, landscape compositions were more common, such as the "Comitiva Regia" of 1879, a luxurious edition with 64 chromolithographs commemorating the marriage of Alfonso XII and María Cristina de Habsburgo-Lorena.

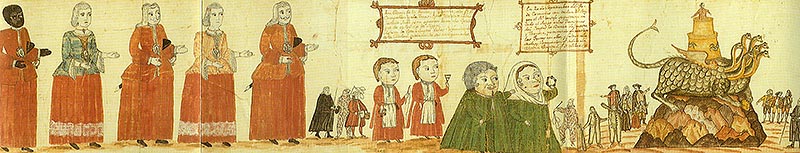

Procession of Our Lady of Roussillon (mid-19th century).

In addition to the published publications, original watercolour drawings have also been preserved, in attached strips, although not in the format of a roll, as is the case of two ordos of the "Corpus Christi Procession in Seville", corresponding to 1747 (Nicolás de León Gordillo) and 1866 (Antonio María de Vega), the latter commissioned by the Dukes of Montpensier and currently in a private collection in Madrid. In the same vein is the "Álbum de la procesión del Corpus de Valencia" (Album of the Corpus Christi procession in Valencia) by the Carthusian friar Bernardo Tarín y Juaneda (after 1889).

Corpus Christi Procession in Seville. Fragment (1747).

The only original scroll preserved, apart from the one exhibited for the first time in this virtual exhibition , is the unusual "Rollo del Corpus de Valencia" (1824), a strip of paper measuring 17 cm x m, of unknown author and of popular and naive character, which combines cuttings and watercolor drawings to describe the procession with a naive realism and colorful coloring.

Rollo del Corpus de Valencia. Facsimile (1824).

It is safe to say that the Crystal Rosary of Zaragoza has become one of the most important and transcendental devotional manifestations, not only in the religious life of that city, but also in the rest of Spain. In fact, it has become one of the most important attractions of the Pilar festivities, with the decorative lanterns standing out above all the rest, which are a popular tradition that is well extended to an event that is difficult to compare, typical and characteristic of the city of the Ebro.

This is not the time to undertake a detailed study of the procession in question, nor of its historical development, as there are many interesting monographs on the subject that amply cover the intricacies between its foundation and the present day; it is sufficient to sketch a few brief outlines of its origin and composition, in order to contextualise the watercolour in the form of a scroll, and justify its subsequent transcendence in other traditions, both inside and outside Aragon.

The Crystal Rosary of Zaragoza arose as a result of the canonical institution of the Brotherhood of the Most Holy Rosary of Our Lady of the Pillar (1889), at a time of exaltation of the aforementioned internship, promoted in the universal church by Pope Leo XIII and in the metropolitan church of Zaragoza by Archbishop Francisco de Paula Benavides y Navarrete.

Starting from the base formed by the movable goods that had been part of the rosary of the dawn, new elements were soon incorporated, including the glass lanterns designed by the architect Ricardo Magdalena. Initially, hand-held lanterns were made to symbolise each of the parts of the rosary prayer that the devotees prayed (Our Fathers, Hail Marys, Glorias and the Litany), while in later years large lanterns were added, carried by costaleros, to symbolise the mysteries of the rosary (Joyful, Sorrowful and Glorious). As different civil, religious and military institutions and associations joined the aforementioned internship , the parading trousseau gradually increased in number, in a process that continues to this day.

Procession of the Crystal Rosary as it passes along Alfonso I Street. Zaragoza.

Despite the novelty of the addition of the lanterns, the previous elements, such as banners, standards and sculptures, continued to be paraded in the procession, making the Crystal Rosary, also known as the General Rosary, into a internship that brought together the tradition and modernity so characteristic of the period between the centuries. As the last century progressed, this internship gradually languished, both socially and religiously, although thanks to the efforts of all subject of personalities and institutions, in recent decades the procession has re-emerged with renewed strength and participation. The restoration of its elements undoubtedly contributed to this, which in turn made the population aware of the importance of the movable heritage that is part of it.

In any case, and despite the fact that it has a series of original and unique elements, it is not an isolated tradition, but must be inserted into a larger process consisting of the modernisation of the old rosaries of the dawn, manifestations of popular piety during the Ancien Régime. This transformation, which we had the opportunity to study [see bibliography], undoubtedly began in Zaragoza at the end of the 19th century, and quickly spread to other towns in Aragon (Calatayud, Tauste, Borja and Híjar) and in Spain (Pamplona, Vitoria, Haro, Atienza, Sigüenza, Castellón and Valladolid, among others).

Looking at the history of this popularly religious sample , we know for sure that until 1898 there was no strict order within the procession, when the canon José Nasarre Larruga systematised and published it, although without any artistic purpose. In fact, such was his success that a year later he was commissioned to do the same for the procession of lanterns of the Virgen Blanca in Vitoria. Until then, the order could only be guessed at through the press, which in turn probably received it from the confraternity itself; a simple comparison of the 1896 and 1897 orders reveals extremely significant variations.

The roll reproduces that of 1897, which was the basis on which Nasarre based his definitive order, although with some variations, hence the importance of the watercolour, which represents the end of a cycle of training and the beginning of a new period of plenitude. It is most likely that the author observed the procession in situ, taking some sketches from life, to later transfer them to paper, following the official order, which seems to have contained some errors, including associations that are only reflected in the press that year of 1897, such as the "high school de la Asunción" (instead of Anunciación), of which there is no news in Zaragoza, or the "Esclavos de María", perhaps confused with the association de Esclavas de María, which always paraded and officially did not. They could also be the Slaves of Jesus of Nazareth -and not of Mary-, who did not parade in the procession. There are also three "lanterns of the living rosary", which were probably never made. This clear analogy between the watercolour and the Aragonese press, reproducing the same errors, can also be detected in the nomenclature used by both. Be that as it may, it is a unique and exceptional document.

With complementary information from the press and the bibliography of the time, it is possible to identify the internship totality of the institutions and artistic goods that took part in the procession in 1897, highlighting the more than four hundred lanterns, which in their day were valued at 50,000 pesetas. The acceptance of the procession, which began on the 13th at 6:00 p.m. and average , was general, and in the press at the time it could be read that the balconies to watch the procession fetched very high prices. It is known that the general lighting was switched off and the procession caused a B effect on the population during its route: Alfonso I, Manifestación, Mercado, Cerdán, Coso, Don Jaime, place de la Seo, calle y place del Pilar by the high door.

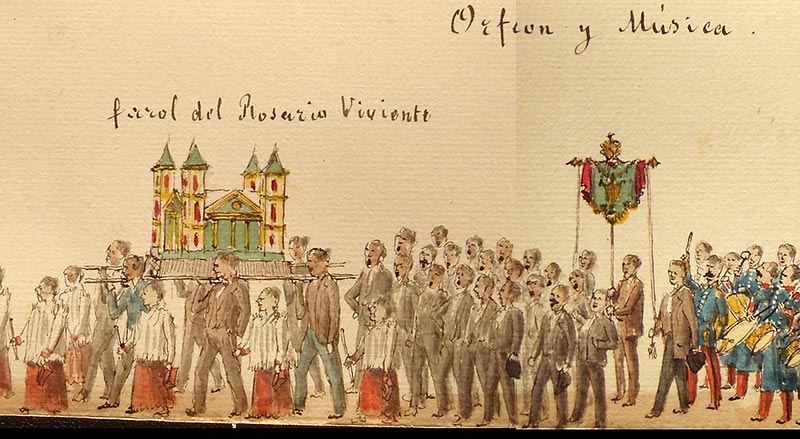

The procession, which begins with a cavalry section of the Guardia Civil and ends with a military infantry picket with the national flag, is adorned along its route with successive choirs (sochantres, infantes...), including the Orfeón Zaragozano, founded in 1895 and directed at that time by José Orós, known as the Orfeón Zaragozano, which was founded in 1895 and directed at that time by José Orós. director rondalla and orchestra. They were accompanied by instruments, in almost all cases military bands, belonging in 1897 to the regiments of Alba de Tormes, Infante and Gerona. Along its eleven metres, they parade both individual personalities and social groups, institutions and associations of all kinds subject. By rule , the members generally wear their best clothes, sporting the badges of their respective associations. The regional costumes that are so fashionable today are only a few exceptions in the procession. Despite being a simple and curious souvenir of the event, without a purely artistic purpose, the author takes pleasure in attitudes, small details, curiosities and anecdotes that justify its journalistic nature.

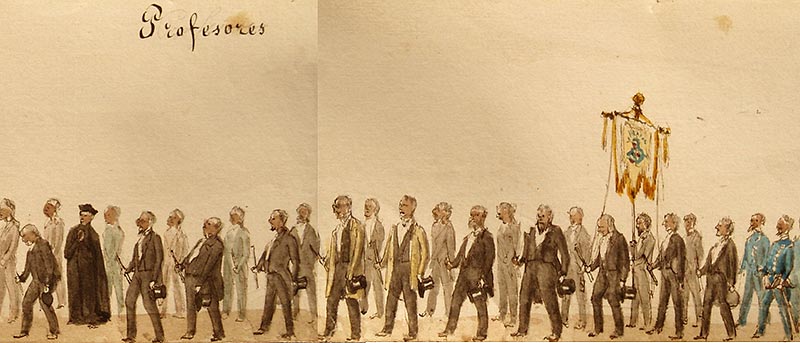

Civil Guard Section.

Among the educational institutions that form part of the Saragossa roll are both private academies and public bodies. Dressed as cadets are the students of the high school de Nuestra Señora de la Asunción, perhaps due to a typographical error, as it must have been a military preparatory academy, although it has not been possible to verify this. The students of the high school Politécnico Nuestra Señora del Pilar, misidentified in the press as "de San Felipe y San Pablo", are also listed. Founded at the end of 1871 and then located in Calle Don Jaime (41-43), it admitted boarders, day pupils and those on average pension, and taught programs of study of first and second letters, as well as baccalaureate, university courses and training military. In turn, the Commission of the Senate of the University of Saragossa, an institution established in the capital since 1542, could not be left out. It is also known from the press that the high school del Salvador (Jesuits), refounded in 1871, took part. Some of its students, as well as Piarist schoolboys, also formed part of the choirs that adorned the procession.

Lecturers at the University of Zaragoza.

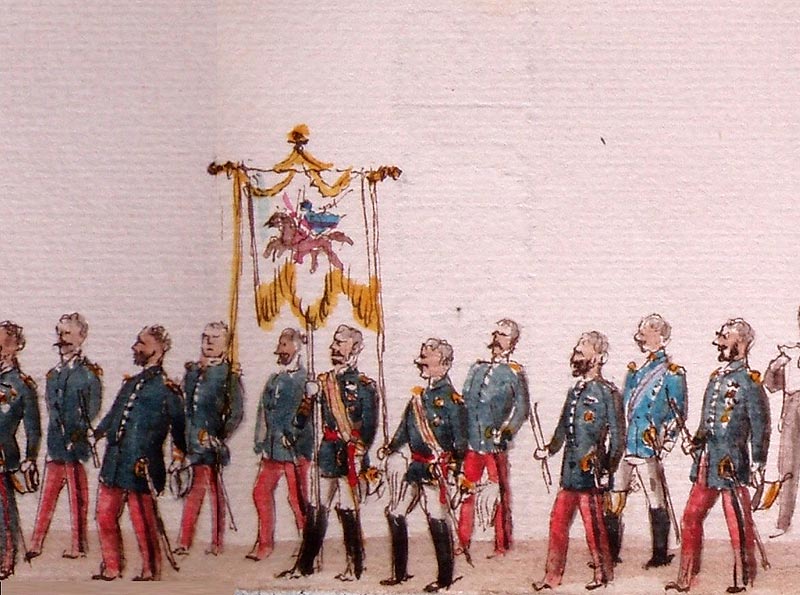

As far as civil groups are concerned, firstly we find the association "El Ruido", which was a comparsa re-founded as a charitable institution in 1896, dedicated from then on to organising raffles and collecting donations to help Aragonese soldiers returning wounded or sick from the war in Cuba. reference letter The Sociedad Protectora de Jóvenes Obreros y Comerciantes, result of the merger of the Escuelas Católicas de Obreros and the Escuela Recreativa de Comercio in 1889, was also portrayed, becoming from then on the focal point of social Catholicism in Zaragoza as far as training was concerned. At the same time, the members of the Red Cross, whose founding assembly took place in December 1870 and of whose Navarrese branch the artist of the watercolour was a founder. By 1874, despite economic difficulties, it had two commissions in Calatayud and Alhama, and a women's section. At the time of the watercolour, it collaborated, together with the preceding association , in the attendance of the Aragonese colonial soldiers. Catholic journalism is represented in the management committee of the Catholic weekly "El Pilar", a magazine founded in 1883 as an instrument for the dissemination of Pilarist devotion, which still retains some of its founding aims today: Aragonism, Zaragozanism, defence of Christian values, and a certain critical spirit. Finally, the members of the Real Maestranza de Caballería paraded, one of the five existing in Spain, with origins in the 16th century and re-founded as such in 1819, due to its special resistance during the War of Independence. They were accompanied, also in full dress, by the officers of the Military Academy of Zaragoza.

Real Maestranza de Caballería.

There are also many pious associations of a universal nature, such as the Apostleship of Prayer, a Jesuit foundation of 1877, merged in the church of San Felipe (1882) with the Pious Union of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, whose members were obliged every day at different times of the day and night to pray a mystery of the rosary, to the extent that they all prayed the rosary constantly. Among them is the Archconfraternity of the Daughters of Mary, which followed the rules adopted by the Congregation of the Daughters of Mary of Barcelona (1849). A refuge for young unmarried women against the "dangers of the world", their spirituality was oriented towards passive virtues (individual morality), ornamental worship and charity. In the same vein, and following the model of the original Paris foundation (1850), was the association de Madres Cristianas, founded in Saragossa in 1877, whose main goal was "to offer their prayers to draw down on their children and their families the blessings of heaven". The watercolour also shows the lecture de San Vicente Paúl del Pilar, whose members, following their Parisian (1833) and Madrid (1850) counterparts, became position for the poor and sick, whom they visited regularly and helped financially. At the same time, two secular orders with similar characteristics and origins (17th century) were registered: the Venerable Third Order of Carmen of the parish of San Pablo and the Venerable Third Order of San Francisco de Asís of the now disappeared monastery of Santa María de Jerusalén. goal Finally, the association de Hijas de María Inmaculada y Santa Teresa (1875), a subsidiary of the Tortosa congregation, attended, not as a congregation but as a private individual, whose aim was to enliven the fervour and piety of the young women, accustoming them to a quarter of an hour of daily meditation.

lecture de san Vicente Paúl del Pilar.

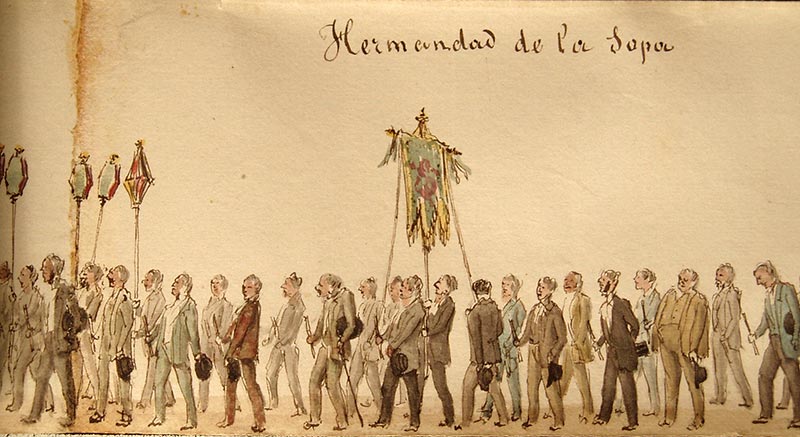

Apart from the universal brotherhoods and the Brotherhood of the Most Holy Rosary of Our Lady of Pilar, which organised the procession, the watercolour depicts the presence of associations unique to Zaragoza, such as the Brotherhood of the Holy Rosary of the parish of San Pablo, which was formed after the secularisation of the Dominicans and whose aim was the sanctification of its members through devotion to the rosary, goal . The Royal Brotherhood of the Most Precious Blood of Christ, founded in the 13th century and therefore the oldest penitential brotherhood in the city of Zaragoza, also paraded. An institution core topic in the organisation of Holy Week in Zaragoza, its functions included the accompaniment of those condemned to death and the collection of helpless corpses, a task that it still carries out today. The "Hermandad de la Sopa" (Brotherhood of the Soup), the popular name by which the Congregation of Nuestra Señora de Gracia de Seglares Siervos de los Pobres Enfermos del Santo Hospital Real y General de Zaragoza was known, also took part in the procession, as from 1779 it took on the obligation to distribute a daily breakfast consisting of oil soup. The congregation, made up mainly of lay people, helped the poor and sick in some of their religious practices and also provided them with some financial assistance financial aid . association Finally, we can see the members of the Royal Congregation of the Annunciation and Saint Aloysius Gonzaga, a Marian congregation founded and established in the church of the Jesuit Fathers in 1860, whose mission was to form true Christians who sought not only their own sanctification but also that of others. In the watercolour they are accompanied by the pupils of high school del Salvador, mentioned above reference letter.

Brotherhood of "la Sopa".

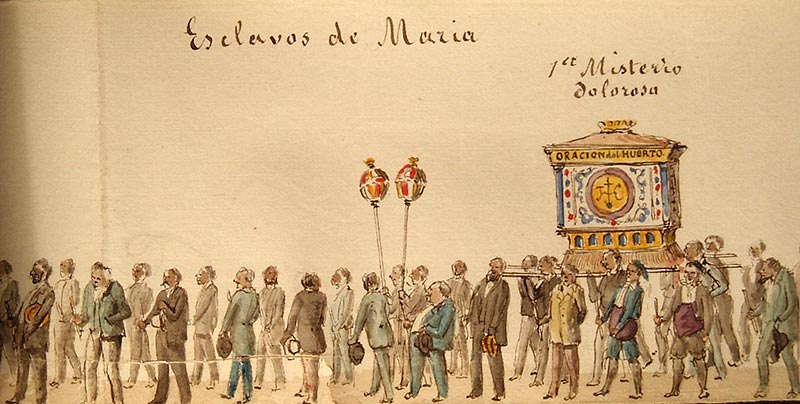

Apart from the above associations, the watercolour and the press show that a association de Esclavos de María (Slaves of Mary) paraded in the procession, which does not appear in any other year of the procession. As has been mentioned, there did exist in Saragossa a association of Esclavas de María Santísima de los Dolores which had been based in the parish of San Pablo since the sixties of the 19th century, so it is likely to be a typographical error. Another possible hypothesis would justify the presence of the author, an active member of the civil and religious society of the capital of Navarre, in the city of the Ebro, as in 1897 the bicentenary of the founding of the Rosary of the Slaves of Pamplona Cathedral was celebrated, association very similar to the one in Zaragoza, which may have been invited to take part in the procession. In this sense, it could be a representation of the Pamplona corporation, which curiously enough, as in Zaragoza, from that year onwards moved the celebration from mornings to afternoons; it also began to modernise its lanterns, which were commissioned from the same workshops as those of the Crystal Rosary.

Slaves of Mary.

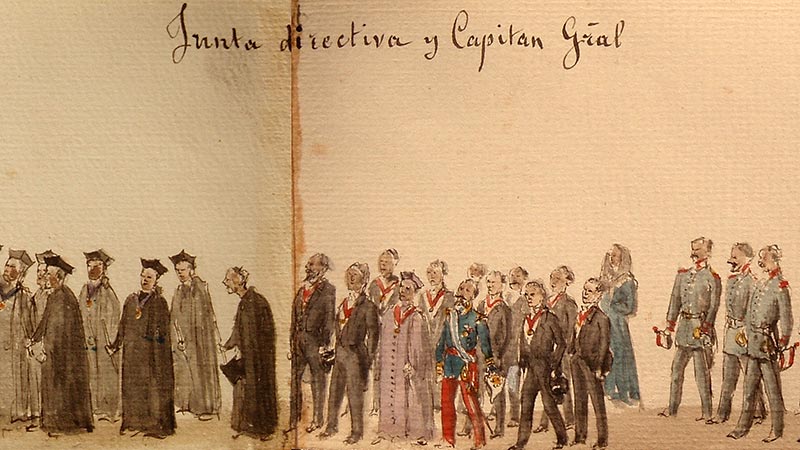

As for the institutions of temporal and spiritual government of the capital, there was a commission from Zaragoza City Council in full dress, as well as other representatives of the clergy of the parishes and the cathedral chapter. Also present were the management committee of the Royal Rosary Brotherhood, accompanied by the Captain General of the place, representing Alfonso XIII, and the Archbishop of the city.

management committee of the procession.

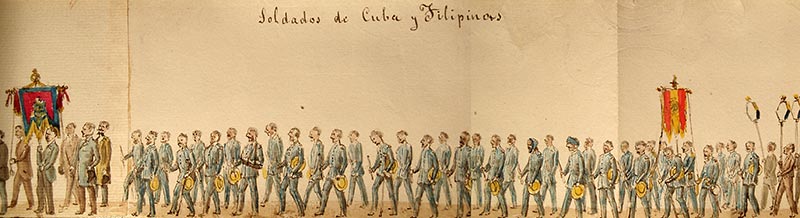

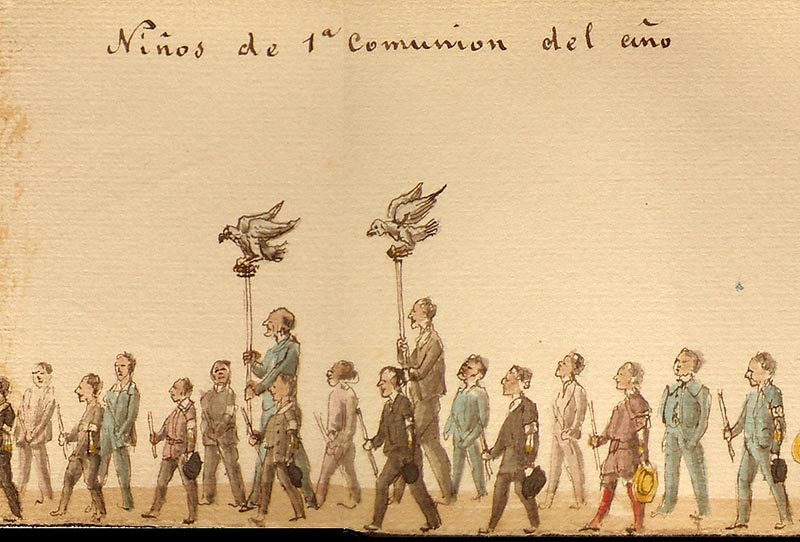

Apart from the institutions, various groups also took part in the 1897 procession, such as the residents of the old parish of Santa Cruz, in the form of a large family; the children who had received communion that same year, dressed in their best clothes; the celebrated infantiques of the cathedral, some seventy, with their colourful robes; the pilgrims, in true Jacobean style, with drums, pumpkins and scallops; the pilgrims, in the purest Jacobean style, with staffs, gourds and scallops, who are known to have been accompanied in thanksgiving by the association of Our Lady of Bonaria, founded by the 113 Aragonese survivors - through the intercession of the Virgin of Pilar - of the shipwreck of the steamship Bellver in 1894 on their way back from the great workers' pilgrimage to the Vatican; and, finally, a hundred battered soldiers from Cuba and the Philippines, dressed in their characteristic "rayadillo" who also attended in thanksgiving, accompanying the association "El Ruido" to which reference letter has been referred to above. According to the press, they were arranged in two rows and caused "great enthusiasm in the immense crowd that witnessed the procession". Only a year earlier, the promoting confraternity had organised a novena of rosaries in its favour inside the church of El Pilar.

Colonial soldiers.

Apart from the procession itself, the Crystal Rosary is particularly noteworthy for the enormous movable heritage that still accompanies it today, made up of its characteristic lanterns, which represent the different parts of the rosary, and the numerous banners that escort the civil and religious corporations. In this sense, the watercolour is very illustrative, as it details the elements that were paraded, some of which no longer exist today.

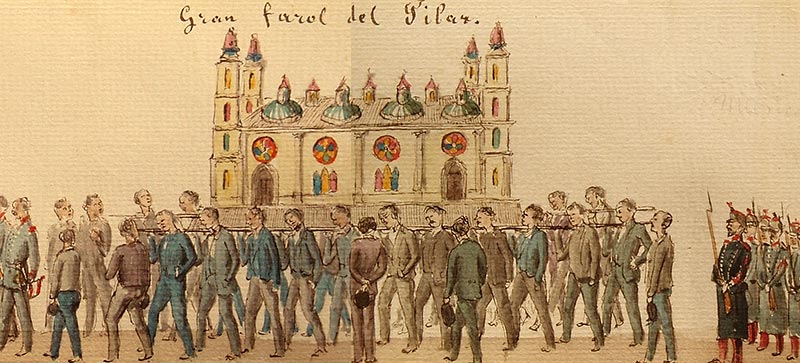

As far as the lanterns are concerned, it is not the purpose of this study to carry out a detailed study of each one of them, but to identify the monumental ones that appear in the watercolour of agreement with the bibliography and the documentation. The basis of the procession are the fifteen lanterns representing the joyful, sorrowful and glorious mysteries, in Byzantine Gothic style. They were designed by the Zaragozan architect Ricardo Magdalena and built in the prestigious workshop of the glassmaker León Quintana in 1890. They were paid for by illustrious personalities, institutions and by popular demand. They are identifiable in the watercolour, although they show certain variations from the originals. A year later, Quintana himself gave the Gran Cruz del Rosario (Grand Cross of the Rosary), which heads the procession in the roll. Accompanying the Town Hall are two very deteriorated lions, the work of Valero Tiestos Guimbao, donated in 1875. The procession is closed by the impressive lantern from the Temple of El Pilar, of enormous dimensions donated by Policarpo Valero y Bernabé, magistrate and mayor of Épila, as a thanksgiving offering in 1872. In the watercolour it appears after the restoration of 1895, as the four towers of the basilica in Zaragoza are already standing.

First Glorious Mystery.

Grand Cross of the Rosary.

Lantern of the church of El Pilar.

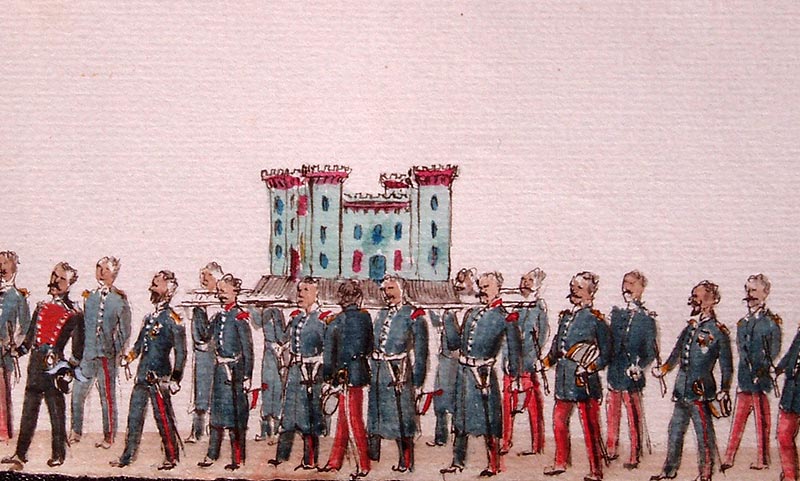

Apart from those preserved, there are some that have been lost, such as the lanterns of the eagles with a pillar in the middle, of which only drawings are preserved, and which were donated by José Alejandro Mainar in the mid-18th century. There is also a castle, probably the survivor of two built, one Spanish and the other Roman, by Mariano Tiestos according to project by Alejo Pescador in 1855. What is unusual is the appearance of three lanterns of the living rosary, in the form of basilica temples, of which there is no documentary evidence (only in the watercolour and in the press), as mentioned above. Perhaps they correspond to the three temples that were in procession with Saint Braulio, Saint Indalecio and Saint James, although it is impossible to certify this. The Arca de Alianza (Ark of the Covenant), also made by Tiestos according to Pescador's sketch and donated in 1875, is also missing.

Antique lanterns of the eagles.

Antique lantern with medieval castle.

It is also known that there were images, although the roll only reproduces the image of Saint Domingo de Guzmán, at the time founder of the religious internship , in the first steps of the retinue. It was donated in 1891 by Carmen Correa, a great devotee of the Rosary, so that from then on it could be paraded in the procession. As a curiosity, although in the watercolour it can be clearly seen that he is carrying the rosary, he appears dressed as a Franciscan. The image, now a vestment, perhaps conceals a Saint Francis of Assisi transformed into Saint Dominic for the occasion.

Sculpture of Saint Dominic de Guzmán.

As far as the banners are concerned, the watercolour sample shows twenty-one of them, some of which are easy to identify. The problem lies in the fact that not all the institutions had banners and the organising confraternity itself or the cathedral chapter temporarily ceded them. Also, due to their fragility, many of them have disappeared, which adds to the difficulty of capturing them in detail in a small watercolour in which practically only the colours can be seen. However, through the press and bibliography it is possible to recognise some of them. The study is limited exclusively to those that appear in the watercolour and which are identifiable, visually or in documentary form, leaving out such important banners as that of "La Venida" (18th century), as the chapter does not carry it in the representation (although it is known for sure that it was paraded and was valued at 5.000 duros), that of Nuestra Señora del Pilar from 1840, because the Town Hall does not carry any insignia either, except the city flag (it is also known from the press that it was planned to parade) or that of the 1880 Madrid pilgrimage, carried by the pilgrims from Rome and given as a gift by the Pilarist congregation of Madrid.

In the first quarter of the procession, the first of these is carried by the students of the high school Politécnico, with a Virgin on the column on a blue background. It is followed by the ladies of the Apostleship of Prayer, with a Heart of Jesus on a pink background. Behind them, the Archconfraternity of the Daughters of Mary carried a banner with the monogram of Mary on a pink background. Immediately after, the lecture of San Vicente Paúl carries a banner with the Virgin on the column on a blue background, although the documentation states that it used to carry a painted one, with the Virgin in an oval on white satin, decorated with garlands and embroidered in gold. The association de Madres Cristianas wears one with the emblem of the cross embroidered in blue and decorated with a garland. The first quarter of the procession is closed by the residents of the parish of Santa Cruz, who carry one similar to the previous one, with the same Christological emblem, although on a pink background.

Sacred Heart banner.

In the second part of the procession, according to Nasarre Larruga's order, the next identifiable, on a green background, was the "precious banner" of the Brotherhood of the Rosary of the parish of San Pablo, with immaculist iconography. A blue banner also paraded with the Virgen del Carmen of the Venerable Third Order of the parish of San Pablo. Meanwhile, the sisters of the Brotherhood of the Rosary were accompanied by a lilac banner, with the apparition of the Virgin of Pilar to Santiago, and the essay of the magazine "El Pilar" carried the banner of Our Lady of Pilar, in gold and silver on blue-green satin, a gift from the widow of the embroiderer Vicente Cormano. On the other hand, a Eucharistic banner with a chalice on a blue background accompanied the children who had received their first communion that year, while the infants, located immediately after, carried one with the effigy of Saint Dominic of Val.

Standard of Saint Dominic of Val.

In the third quarter of the retinue, the banner of the association "El Ruido" can be seen, with a design of two intertwined Spanish flags with the arms of the kingdom of Aragon in each corner. At the same time, the accompanying colonial soldiers carried the colours of the nation as insignia. They were followed by the Red Cross delegation, with a simple composition made up of its emblem on a navy blue background, and the commission of professors from the University of Zaragoza, carrying the painted banner of Saint Braulio, patron saint of the institution, superimposed on a white satin with floral motifs. This was followed by two military banners: one, that of St. George, embroidered in gold, silver and silk on white and red, carried by the Royal Cavalry Cavalry Order; and that of St. James, in red velvet, embroidered in gold and silver, with the image of the apostle painted on canvas, which was carried by General Braulio Campos. It was made by the aforementioned Vicente Cormano in 1851 and paid for by Canon Manuel Pomar.

Santiago banner.

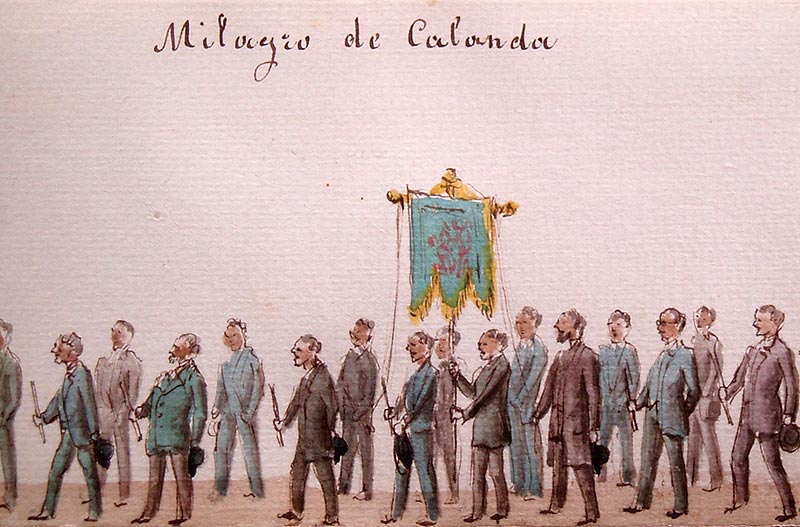

In the last section of the procession, the very valuable banner of the Miracle of Calanda stands out, richly embroidered in silks and gold, on red damask (although in the roll it appears in light blue), made by the widow of the aforementioned Cormano in 1867, and which was normally carried by the civil governor of Zaragoza. The design, at position by Mariano Pescador, includes the coats of arms of Spain, Zaragoza and the Cabildo, while the side falls bear Saint Valero and Saint Braulio; the obverse bears the monogram of Mary. The standard-bearer, bearing the arms of the capital, closes the parade.

Calanda Miracle Banner.

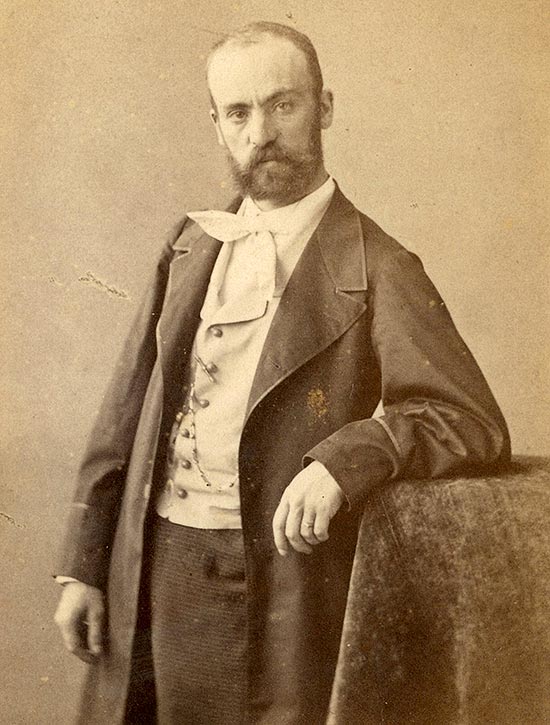

The author of the watercolours is Aniceto Lagarde y Carriquiri (1832-1909). He came from a family of merchants from Béarn and married the sister of Antero de Irazoqui, a leading national politician. He graduated as a civil engineer from the Ecole Centrale des Arts et Manufactures in Paris (1858), becoming the director of Roads of the South department of the Province of Navarre (1869). A convinced liberal, he took an active part during the Carlist War, not only in the civil and military operations during the blockade of Pamplona, but also as a war correspondent, sending his sketches to important magazines such as La Ilustración Española y Americana, and producing many watercolours, of which recent monographs have given an account. He was one of the founding members of the Red Cross of Navarre, forming part of the select group known as "Los camilleros de Landa" (Landa's stretcher bearers), who first acted in 1872. He was a teacher at the School of Arts and Crafts in Pamplona, vice-president of the Monuments Commission of Navarre, and actively participated in undertakings of great importance, such as the safeguarding of the Royal Palace of Olite, the recognition and dignification of the heart of Carlos II "the Bad", or the transfer of the remains of Espoz y Mina to Pamplona from La Coruña, among many others of interest. His work in this field led to his appointment as a corresponding member of the Royal Academy of History.

Portrait of Aniceto Lagarde y Carriquiri.

He also held important posts at the association Euskara de Navarra, working in its Industry section. In any case, his occupations as a provincial architect and the nationalist drift that the aforementioned institution underwent meant that he first refused the presidency (1880), and later left leave (1882). board member of the Orfeón Pamplonés, he was also among those who promoted the cultural association "El Liceo" (1881), and actively participated in other institutions that shaped the rich cultural life of fin-de-siecle Pamplona, such as the association Musical Santa Cecilia and the Orfeón Pamplonés.

A representative on many different commissions, he worked with Maximiliano Hijón, both on the decoration of the throne room of the Palace of Navarre and on the construction of high school Provincial. His work was not only centred on purely civil projects (the road from Pamplona to the station, the Amézcoa road, the road from Roncesvalles to Valcarlos, the bridges of Sangüesa, Liédena and Carcastillo, and project de ferrocarril de los Alduides de Navarra, among others), as it is known that he designed the mausoleum of the Marquis of Jaureguizar - the design is still in private hands - and the altar of the parish church of San Esteban de Vera de Bidasoa (1866), the town where his wife, María de Irazoqui, was from. He also stood out as a wine producer, since he received municipal permission to make wine on his famous Lagarde estate, which has now disappeared. Some of his wines were exhibited and tasted at the 1888 Barcelona Universal Wine Fair exhibition .

"El Ruido de Zaragoza", in Blanco y Negro [30/05/1896].

bulletin Oficial del Obispado de Vitoria [1896].

bulletin Oficial del Obispado de Zaragoza [1889-1898].

Diario de Avisos de Zaragoza [13/10/1897].

Heraldo de Aragón [13/10/1897].

La Correspondencia de España [ 13/10/1896].

La Correspondencia de España [ 13/10/1897].

La Unión Católica [ 14/10/1897].

"Hermandad de la Sopa", in Gran Enciclopedia Aragonesa Online.

ALADRÉN FERNÁNDEZ, J., "El rosario salterio de fieles y expresión de su peculiaridad religiosa: el Rosario de Cristal", report Ecclesiae, n.º 20 (2002), pp. 536-566.

ALDEA HERNÁNDEZ, A., "La procesión valenciana del Corpus según las representaciones iconográficas de fray Bernat Juanera", in Religiosidad y ceremonias en torno a la eucaristía: conference proceedings del simposium, El Escorial, 2003, vol. 2, pp. 753-776.

AMADES I GELATS, J., Costumari Català [5 vols.], Barcelona, Salvat, 1982.

CATALÁ GORGUES, M. A., El rollo de la procesión del Corpus: un curioso documento de principios del siglo XIX, Valencia, Valencia City Council, 2003.

ESTEBAN MOLINERO, J., "Aportación del catolicismo social a la Education popular en Aragón (1857-1923)", Participación educativa, n.º extraordinario (2010), pp. 91-107.

FATÁS CABEZA, G., "Los años fundacionales", in La Cruz Roja y Zaragoza: 140 años conviviendo, Zaragoza, Spanish Red Cross, pp. 11-24.

GASCÓN DE GOTOR, P., Rosario de Nuestra Señora del Pilar: su origen y development, Zaragoza, Imprenta de Calixto Ariño, 1891.

GÓMEZ URDÁÑEZ, J. L., Religión y muerte. La Hermandad de la Sangre de Cristo de Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Institución Fernando El Católico, 1980.

HEARN, M. K., How to Read Chinese Paintings, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008.

HERNÁNDEZ MARTÍNEZ, A., "El Rosario de Cristal de Zaragoza: aspectos artísticos de una devoción religiosa", in Homenaje a Antonio Durán Gudiol, Huesca, high school de programs of study Altoaragoneses, 1995, pp. 427-440.

HUHTAMO, E., Illusions in Motion, Cambridge, The MIT Press, 2013.

JACKSON, A. and JAFFER, A., Maharaja: the splendour of India's royal courts, London, Victoria & Albert Museum, 2009.

LAGUÉNS MOLINER, M. and ALADRÉN FERNÁNDEZ, J., El Rosario de Cristal de Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Caja de Ahorros Inmaculada, 2007.

LLEÓ CAÑAL, V., 8 tiras dibujadas de la procesión del Corpus de Sevilla, 1747, Seville, Seville City Council, 1992.

LLEÓ CAÑAL, V., Fiesta Grande del Corpus Christi en la Historia de Sevilla, Sevilla, Ayuntamiento de Sevilla, 1992, p. 32.

MARTÍN LATORRE, P., Nuestra Señora la Blanca, historias de su cofradía, Vitoria, Diputación Foral de Vitoria, 2003.

MELERO NAVARRO, J., El Rosario de Cristal de Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Cofradía de N. S. Rosario, 2008.

MORALES SOLCHAGA, E., "El Rosario de los Esclavos de la Catedral de Pamplona en el contexto peninsular", Cuadernos de Etnología y Etnografía de Navarra, n.º 86 (2011), pp. 127-146.

NASARRE LARRUGA, J., El Rosario de Nuestra Señora del Pilar, Zaragoza, Mariano Salas, 1898.

PÉREZ GOYENA, A., essay de bibliography Navarra, Pamplona, Diputación de Navarra, 1962, vol. 8, pp. 111-113.

PETERSON, J. L., "The Historiscope and the Milton Bradley Company: Art and Commerce in Nineteenth-Century Aesthetic Education", Getty Research Journal, no. 6 (2014), pp. 174-184.

REVUELTA GONZÁLEZ, M., La Compañía de Jesús en la España Contemporánea, Madrid, Universidad Pontificia de Comillas, 1992, volume 2, p. 634.

ROLAND, J., Life in England in Aquatint and Lithograph, 1770-1860, London, Curwen Press, 1953.

SALAS VILLAR, G., "Santiago de Masarnau y la implantación del piano romántico en España", Cuadernos de Música Iberoamericana, vol. 4 (1997), pp. 197-222.

SANCHO IZQUIERDO, M., Zaragoza: las calles de una ciudad, Zaragoza, El Noticiero, 1962, pp. 45-46.

SOLLOSO GARCÍA, J. M., "El Rosario de Cristal", Revista General de Marina, vol. 254 (2008), pp. 59-64.

TORRIJOS BERJES, S., El Rosario General de Nuestra Señora del Pilar, Zaragoza, El Noticiero, 1941.

WATANABE, M., Storytelling in Japanese Painting, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011.