A look at 19th century Navarre: some views by Aniceto Lagarde

EDUARDO MORALES SOLCHAGA

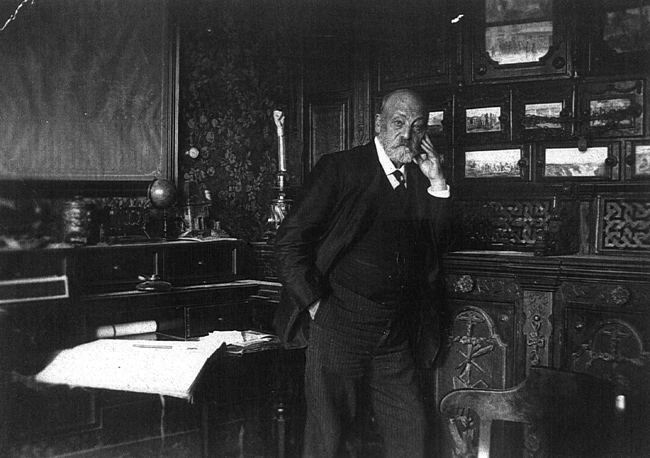

The author of the watercolours is Aniceto Lagarde y Carriquiri (1832 - 1909). He came from a family of French merchants and was married to the sister of Antero de Yrazoqui, an important national politician and representative of the Conservative Party in both houses. A civil engineer and convinced liberal, he took an active part during the Carlist War, not only in the military operations during the blockade of Pamplona, but also acting as a war correspondent, sending his sketches to important magazines such as "La Ilustración Española y Americana", and producing many watercolours, of which recent monographs have given an account.

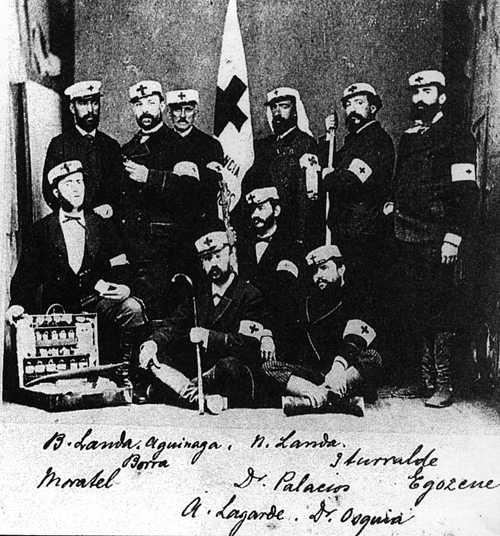

He was one of the founding members of the Red Cross of Navarre, forming part of the select group known as "Los camilleros de Landa" (Landa's stretcher bearers), who were first active in 1872. He was a member of the Pamplona School of Arts and Crafts and of the Monuments Commission of Navarre, actively participating in undertakings of great importance, such as the safeguarding of the royal palace of Olite, the recognition and dignification of the heart of Carlos II "the Bad", or the transfer of the remains of Espoz y Mina to Pamplona from La Coruña, among many others of interest. His work in this field led to his appointment as a corresponding member of the Royal Academy of History. He also held important posts in the Basque Association of Navarre, working in its industry section. In any case, his occupations as a provincial architect and the nationalist drift that the aforementioned institution underwent led him first to decline the presidency (1880) and later to leave leave (1882).

board member of the Orfeón Pamplonés, he was also among those who promoted the cultural association "El Liceo" (1881) and actively participated in other institutions that shaped the rich cultural life of fin-de-siecle Pamplona. He worked with Maximiliano Hijón, both in the decoration of the throne room of the Palace of Navarre and in the construction of the Provincial Institute. His work was not only centred on purely civil undertakings, as there is evidence that he designed the chapel-mausoleum of the Marquis of Jaureguizar - the design is still in private hands - and the altar of the parish church of San Esteban de Vera de Bidasoa (1866), the town where his wife, María de Yrazoqui, was from.

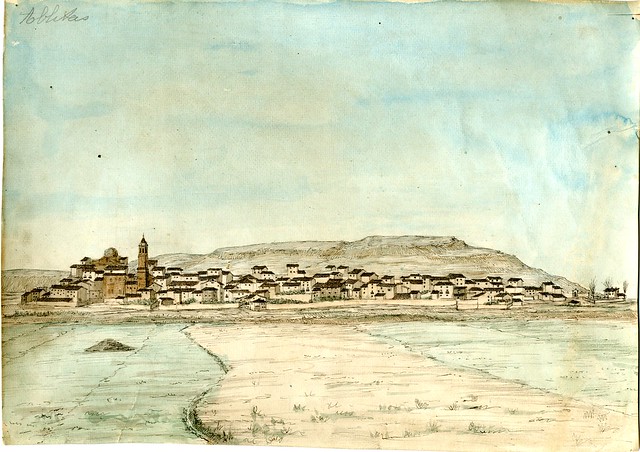

This virtual visit analyses almost twenty views of towns and cities in the region of Navarre. If we analyse Aniceto Lagarde's known work, we can state categorically that landscape and views of localities were his favourite genres, and a good sample of this is preserved in lithographs in illustrated publications and in watercolour drawings preserved in private hands.

The repertoire of watercolours presented here, a digital copy of which is kept at the Cátedra de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro, has remained in private hands in recent years, although it undoubtedly belonged to Aniceto Lagarde's personal collection, part of which is carefully preserved by his relatives.

The same group includes a view of Corella and another of the Fitero Spa, which are also in private collections. Other views of towns in Navarre have probably been lost, although there is evidence of drawings and watercolours of towns outside Navarre, such as Alhama de Aragón and Montserrat. In turn, in the Album of the Blockade of Pamplona, recently exhibited in the Carlist Museum, there are views of other towns in Navarre, such as Pamplona, Olite, Igúzquiza, Echarri-Aranaz and Tafalla, in order of appearance. There is also a view of the capital in the Mueble del Bloqueo, preserved in private hands.

The origin of the watercolour drawings, which should be dated to the last third of the 19th century, is uncertain. On the one hand, they could be linked to the author's own amusement, who amused himself by taking sketches from life, as can be deduced from his personal file ; on the other, to his work as a war reporter in the Third Carlist War, which had Navarre as one of its main scenes. Finally, it is also possible to link the views to his work as a civil engineer, as he designed many projects in the region, such as the Amézcua road and the Sangüesa and Carcastillo bridges. Be that as it may, the views are a unique document, a testimony to how some towns in Navarre were structured in the last decades of the 19th century.

As far as the layout is concerned, they are presented in landscape format, which makes it possible to describe not only the towns, but also their surroundings. For the larger towns, such as Pamplona, Tudela or Sangüesa, he was obliged to enlarge the surface of the paper, attaching one or more sheets consecutively. As for the process, these are sketches made from life in pencil and then inked and watercoloured in the studio. Unfortunately, over the years they have lost their tonality.

Aniceto's style is a far cry from that of his brother Nemesio, who can be considered a true artist and draughtsman. As described by Urricelqui in his monograph on the Álbum del Bloqueo, Aniceto excelled in his mastery of drawing, employee with topographical rigour, and of watercolour, with which he showed a special sensitivity and which he must have learnt during his stay in Paris.

The collection of watercolours is sample of his engineering training, for although they are invaluable testimonies, they suffer from rigidity and a lack of grace. The purely descriptive aspect outweighs the artistic, which does not detract from the unusual and attractive character of the whole. The inked drawing is sometimes excessively rigid, although the skill in the application of watercolour, an aspect traditionally undervalued, undeniably raises the quality of the views. In fact, the only one in the series that is not polychrome, it stands out - never better said - from the others.

Unfortunately, some of the views could not be identified because, after a century and a half, the profile and structuring of many of the villages has been masked by later buildings and complexes, making it practically impossible to recognise them. This is also the case in some others, due to the simplicity of their forms, the standardisation of the buildings and the absence of recognisable geographical features.

- La Ilustración Española y Americana, Madrid, 1875.

- ANDUEZA UNANUA, P., "Vista de Pamplona" in Juan de Goyeneche y el triunfo de los navarros en la Monarquía Hispánica del siglo XVIII, Pamplona, Fundación Caja Navarra, 2005, pp. 252 - 253.

- FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R. [coord.] El Arte del Barroco en Navarra, Pamplona, Gobierno de Navarra, 2014.

- FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R. [coord.] El Arte del Renacimiento en Navarra, Pamplona, Government of Navarre, 2005.

- FERNÁNDEZ LADREDA, C. [coord.] El Arte Gótico en Navarra, Pamplona, Gobierno de Navarra, 2016.

- FERNÁNDEZ LADREDA, C. [coord.] El Arte Románico enNavarra, Pamplona, Government of Navarre, 2003.

- GARCÍA GAÍNZA, M. C. [coord.] Catalog Monumental de Navarra, Pamplona, Government of Navarra, 1980 - 1987.

- LABEAGA MENDIOLA, J.C., Sangüesa [Panorama nº 22], Pamplona, Government of Navarre, 2011.

- MORALES SOLCHAGA, E., "Personajes ilustres en álbumes familiares del siglo XIX" in Cuadernos de la Cátedra de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro, nº 6 (2011), pp. 127 - 146.

- ORTA RUBIO, E., Tudela [Panorama nº 41], Pamplona, Government of Navarre, 2009.

- TARIFA CASTILLA, M.J., El Monasterio Cisterciense de Tulebras [Panorama nº 43], Pamplona, Government of Navarre, 2012.

- URRICELQUI PACHO, I., Álbum del bloqueo de Pamplona. Memories of a civil war, Pamplona, Government of Navarre, 2008.

- VV.AA. Gran Enciclopedia de Navarra, Pamplona, Caja de Ahorros de Navarra, 1990.