8 February 2007

lecture

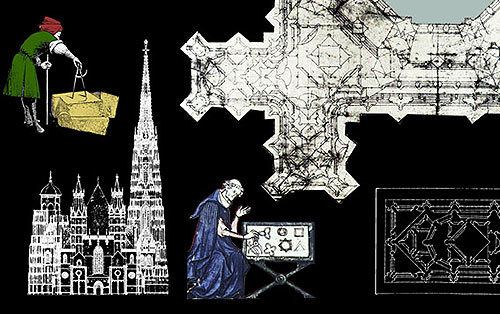

How a cathedral is built

Mr. Joaquín Lorda Iñarra.

University of Navarra

The topic of "building a cathedral" is extremely attractive. In fact, it has become a cliché.

Building a cathedral was the most important undertaking of medieval cities; it required broad citizen participation and the assistance of specialist craftsmen.

Thus, throughout the 19th century, historians were understandably tempted to interpret their protagonists, the ordinary citizens of medieval cities, as "cathedral builders"; while in the skilled craftsmen, their secrets of official document and their guild organization found the nebulous antecedents of Freemasonry.

Moreover, the mixture of popular commitment, religious fervor, and secular independence supported by arcane knowledge is so suggestive that it has repeatedly spilled over into history and into novels; one of its latest exponents is Ken Follet's bestseller, The Pillars of the Earth, "an exceptional evocation of the Age average, with all the force of its violent passions", and perhaps one of Follet's worst novels.

Among those who are more specifically interested in questions of Western architectural history, the construction of European cathedrals has occupied a preferential place, since they are the largest, most expensive and most complicated buildings in history. And cathedrals are the protagonists of the study of styles: they exemplify the distinctly different ways - Romanesque and Gothic - of medieval architectural design , which extended to objects of all scales.

On the other hand, these ambitious buildings have been built with advanced construction techniques, which have improved from the age of average to the 19th century. Similar to what happened in other fields, such as shipbuilding and fortification, the construction of these great buildings put conventional solutions on test and encouraged the search for more ingenious ones: it was an engine of technological innovation. For this reason, the history of its design can be conceived as a continuous growth in technical knowledge, which at each moment has logically responded to the specific problems that arose.

Finally, the construction of cathedrals has an "ethnological" interest: it is an opportunity to talk not only about the great concepts or structural systems, but also about the small and anecdotal history of the trades and skills that were once common and have now disappeared, as well as the tools and machines for transporting and lifting loads, which have been advantageously overcome.

However, among all these complementary stories, there is the growth of a trend that cannot be interpreted in these simple ways, and that gives rise to a story perhaps less known, but of greater human content; and it is the one we are trying to expose in this talk. The architectural designs were not only grandiose, and therefore involved technical complications, and even placed themselves at the limit of their possibilities. But in a way they sought to place themselves at the limit because in this way they increased the value of the architectural design . This led to a very interesting process in which the constructive logic was progressively sacrificed: the design of the building appeared more and more interesting, while its construction led to more and more absurd formulas. A logic of monumentality appeared that is very different from the one that presides over ordinary construction (and naval construction and fortification).