April 24, 2008

Global Seminars & Invited Speaker Series

ENGRAVING IN THE CENTURY OF ENLIGHTENMENT

Engraving and devotional prints in Navarre

D. Ricardo Fernández Gracia

Chair de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro

As degree scroll indicates, the lecture dealt with both material and technical issues related to the prints, as well as everything related to their purpose of provoking the affections and devotions of those who contemplated them.

The intervention, illustrated with a hundred engravings, plates, proofs and drawings, was divided into the following parts: promoters, engravers, printing and distribution, use and function, and iconographic and anthropological interest.

It is well known that during the centuries of the Modern Age, the market for non-religious engravings in Spain was as scarce as the market for religious engravings was abundant, as shown in texts by the painters Jusepe Martínez and Eugenio Cajés, in the first half of the 17th century. Hence the word estampa came to be identified with those engravings that reproduced saints, Christs or Marian images. The prints referring to general devotional themes were supplied by European workshops, while the engravers established in Spanish cities, such as Pamplona, opened those plates which, because of their local or very specific subject matter, could not be imported.

The impulse of devotion was, without a doubt, the primary purpose of religious prints. Sometimes they were used to illustrate thesis of university Degrees , also as authentic talismans and as postulation objects for churches, confraternities and sanctuaries. All those images were destined to the simple people in whom they inspired the same respect and piety as the altarpieces, sculptures and paintings of the temples, at the same time that for a modest price they could have their favorite images to satisfy their particular devotions. In this way, the interest of confraternities and devotees to possess the "true portraits" and the "miraculous images" as they were venerated in the churches, was fully compensated by acquiring in the sacristies, booksellers, stamp dealers or hawkers, the prints of their particular preference.

Among the great centers of distribution we must mention the great sanctuaries such as Ujué, Roncesvalles or the basilica of San Gregorio Ostiense, as well as some fairs and festivals around the feasts of certain images implored for specific needs. The promoters of those prints used to be the religious centers themselves, town halls for their patrons, although in many occasions it was a special devotee, with economic means, the one who made position of the expenses inherent to the opening of the plate, as well as to the first prints.

With respect to the engravers, it is important to highlight the important presence of works by dynasties of Pamplona silversmiths with 50% of the production, the plates opened by Aragonese masters with 18%, those from Madrid with 15%, Romans with 4.5% and other Hispanic Flemish and Italian cities with smaller percentages.

Of the iconographic interest of these pieces we can see some examples that reproduce sculptures and altarpieces that have disappeared, as well as others, especially of Marian devotions, that present images adorned, decorated and dressed in different ways, depending on whether we are in the 17th, 18th or early 19th century. Other prints are perfect exponents of emerging devotions such as that of the Heart of Jesus in plenary session of the Executive Council XVIII century, with a great issue of copies of different sizes and importance, made under the auspices of the Jesuits, and distributed from the Basilica of San Ignacio de Pamplona.

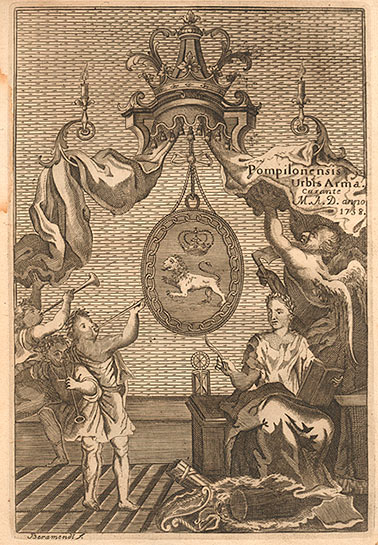

Illustration from the 1759 Pamplona edition of Fr. Nieremberg: On the difference between the temporal and the eternal.