April 24, 2008

Global Seminars & Invited Speaker Series

ENGRAVING IN THE CENTURY OF ENLIGHTENMENT

Ornamentation and illustration of 18th century Navarrese books

Mr. Javier Itúrbide Díaz

Ph.D. in History

The activity publishing house in Navarre throughout the 18th century was particularly intense, largely due to political, institutional and administrative reasons. test Be that as it may, the century begins with three active workshops and ends with six, which means that the demand for printing works was increasing, both from the institutions of the kingdom and from the religious communities and private individuals, to which must be added the printers, who promoted a third part of the published titles.

The technical quality of these works is increasing and evolves from the motley baroque book, with blurred prints and poor quality paper, to the classical style, which uses good paper and boasts a careful typography, balanced with whites and stripped of unnecessary ornaments.

Two thirds of the books have some subject typographic ornamentation, based on motifs, mostly rough and repeated in successive impressions. This resource is more frequent in larger format books, such as folio and quarto. Here the works with ornaments, which can be headers, vignettes, initial letters, fillets, corondels or geometric compositions with printing types, represent almost ninety percent; on the contrary, these ornamental resources are scarcer in the smaller prints, in octavo and sixteenths, where the percentage drops to 50 percent. Thus, it can be seen that the large format book is linked to prestige publishing house, has an ornamentation that embellishes it and, therefore, has a higher price. On the other hand, smaller, widely distributed, low-priced works reduce production costs to a minimum and, to this end, among other measures, do away with all accessory ornamental elements.

The extinction of baroque taste and the consolidation of classicism in the age of Enlightenment is also noticeable in print production. Typographic ornaments become rarer as time goes by, so that at the beginning of the century 80 percent of the books show typographic ornaments and by the end of the century this percentage has been reduced to 61 percent.

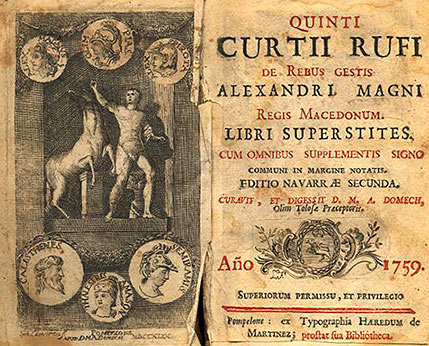

Quintus Curtius, 1759

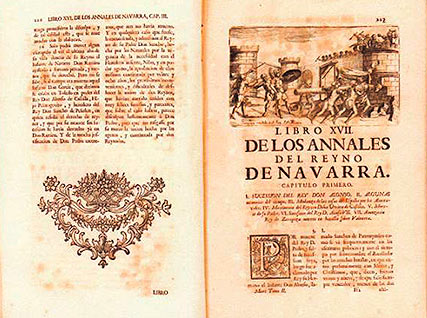

Pamplona has a large number of printing workshops, which work smoothly and guarantee a stress-free life for the owner and his journeymen and apprentices. They are family businesses that in some cases acquire considerable dimensions due to the capitalization and issue of employees. But it should not be forgotten that these workshops are far from the large publishing centers, and that, in final, they have a modest activity, aimed at a small local market and that their printed matter cannot and does not pretend to compete with the large editions of Madrid, Valencia or Barcelona. For this reason, wood engravings, "entalladuras", are perpetuated as an ornamental resource . They are dominated by a crude invoice , a repetitive iconography, which offers a poor artistic balance. Intaglio engraving, on the other hand, is making its way with difficulty, since it requires a more meticulous and, consequently, more expensive procedure . The engravings opened for a certain edition are rare, they correspond to institutional publications, such as the Annals of Navarre, printed in 1684, 1755 and 1766; there are, however, private publishers, with economic resources and taste for quality work , who promote illustrated books, as happens with Miguel Antonio Domech; finally, there is a reduced issue of authors who embark on the adventure of publishing their book enriched with the illustrations they have commissioned for that purpose.

Annales del Reyno de Navarra, 1766

If typographic ornamentation was a common resource in Navarrese books of the 18th century, due to its zero cost, illustration is rarer because it required a significant investment that in some cases represented 45 percent, while the printing of the text required 33 percent and the binding the rest.

The illustrations used are mostly, around 64%, of ornamental subject , followed by those of heraldic topic with 20% and in third place, with a modest 12%, those of pious content. Here, in the printing presses of the capital of Navarre, there are no superb engravings of portraits, landscapes, botany or engineering that occupy the prestigious engravers of the Court.

Since illustrated editions are rare, at the beginning of the century, when the work of a metal engraver was required, it was sought outside Navarre, on the other side of the Pyrenees. Thus, we know of the intervention of engravers from Toulouse in prints of 1706 (Jacques Simonin) and 1714 (Jaime Laval); in the middle of the century, Aragonese engravers were entrusted with important works, such as the frontispiece of the Novísima recopilación de leyes ( 1735, Juan de la Cruz) and the Anales de Navarra (1766, José Lamarca); finally, the official document will be used by craftsmen from Navarre, such as Manuel Beramendi. It should be kept in mind that the work of engraver, because it has a reduced demand, is combined with that of silversmith, with a more constant activity, and with which it has, from the technical point of view, many points in common.

By way of summary, it is worth highlighting the vigor publishing house shown by the Navarre printing presses of the Enlightenment period, the technical and artistic progress they experienced throughout the century, the inexorable withdrawal of the Baroque to assume classicism in typographic patterns and, finally, the systematic use of ornamental motifs in publications, although with a tendency to moderate their manifestations, while illustrated books, for economic reasons, are rare and of inferior quality to the great printing presses of the Court.