30 March 2011

Course

THE CATHEDRAL OF PAMPLONA. A VIEW FROM THE 21ST CENTURY

Art, festivals and liturgy: the great celebrations from the Middle Ages to the present day average

D. Ricardo Fernández Gracia.

Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

The cathedral is a temple with a specific function in the life of the bishopric, as the first church of diocesan life, seat of the episcopal Chair and expression of the liturgical life of the chapter. Times and tastes have transformed the monumental complex, both externally and externally, for purely aesthetic reasons, but also for liturgical reasons and reasons of use and function.

Its stone walls began to be "dressed" with altarpieces and images, especially from the end of the sixteenth century and throughout the next two centuries, in plenary session of the Executive Council Baroque, corresponding to an aesthetic characterized by the integration of artistic specialties, merging them into a whole, and by the capture of the viewer through the senses, always more vulnerable than the intellect.

The integrated arts became a vehicle for the transmission of doctrine and internship power in a field that transcended the temple itself, because in addition to being a cathedral or the place where the bishop's Chair is located, the Pamplona cathedral was governed by a chapter of regular life, not very accommodating to bishops with reinforced authority after the Council of Trent. In addition, the regiment of the city and the political organs of the Kingdom celebrated in its interior the great ceremonies and festivities, sublime expression of how much shapes the culture of the Baroque.

Today it is necessary to have a joint vision of the cultural assets of the cathedral complex, with all the transformations it has undergone over the centuries, without losing sight of the identity and authenticity of the historical document - theunicum- that it possesses as a monument.

From the Age average to the Counter-Reformation

To this must be added the application of a new liturgy, emanating from the Tridentine dispositions that caused the old breviaries to be abandoned in favor of the Roman Ritual of St. Pius V, something that happened around 1585, and the old choir rules, codified in the first half of the 15th century, based on practices that had been common in the cathedral since at least the 14th century, were replaced by new ones, written in 1598, following those of the Primate Cathedral of Toledo. The manager of this last mutation was none other than Bishop Antonio Zapata, who governed the destinies of the bishopric between 1596 and 1600, leaving an everlasting mark with the construction of the sacristy, the main altarpiece and the silver platforms for the Corpus Christi, works of Herrerian imprint, in tune with courtly tastes. The fact that Zapata had been a canon of Toledo was fundamental, both in the choice of some of the themes of the main altarpiece related to San Ildefonso, as well as in the establishment of the new choir regulations.

With those changes, not only did the formulas of prayers, music and rites mutate, but also the general or public processions that had been celebrated in the city since the centuries of the Age average were lost. Under the pretext that "the frequent use of them diminished devotion, they became cloisters."three great medieval processions that took place on the feasts of St. Peter, the Crown of Christ and the Exaltation of the Holy Cross were converted into cloistered processions. The first, perhaps the most solemn, had as protagonist the sculpture of the titular Virgin of the temple, together with the reliquary coffers; that of the Crown of the Lord was celebrated in the Dominican after the feast of the apostles and walked through the streets with the Gothic reliquary of the Holy Thorn. That of the Exaltation of the Cross was the last of those instituted, as a result of the donation of the Lignum Crucis by Manuel II Paleólogo to Carlos III, in 1400 and of this last one to the cathedral, the day of Kings of 1401.

Some processions were maintained and increased, as happened with those of Corpus Christi and San Fermin from 1599 and San Martin from 1566. Others were created anew, as a consequence of the city's vows to San Sebastián and San Roque.

As far as the feasts were concerned, the novelties were also to be noticed with the new times of the Counter-Reformation, in which the needs were different and the models of sanctity were also different. Between 1605 and 1643, the day of the Guardian Angel was a feast of obligation, by episcopal disposition. Later would come the lawsuit of the copatronage between the supporters of San Francisco Javier and San Fermín. The Pamplona seo together with the regiment of the city were the standard bearers of the cause of San Fermín, until the Brief of Alexander VII that declared them both patroni aeque principalesin 1657.

Venue of the great events in singular festivities

Events of a religious nature, but also linked to the Hispanic monarchy, took place inside the cathedral. Oaths of princes, proclamations, obsequies and prayers for different reasons, requested by Austrias and Bourbons, were celebrated in the first diocesan temple.

Among the great religious festivals we must mention the ratification of the board of trustees of San Francisco Javier by the Cortes in 1624 and the immaculist vote of the institutions of the kingdom in 1621, in addition to countless rogations with the images of San Fermin or the Virgin of the Sagrario requested by the city council and organized by the town council, not without friction, disagreements with other civil and ecclesiastical institutions and frequent lawsuits for preferences and precedence, so usual in the society of the Ancien Régime.

All these festivities were surrounded by an unparalleled rhetorical apparatus. The interior of the temple was "hung", that is, it was covered with hangings, tapestries and pastries appropriate to the reason for the celebration, reserving those of greater pomp and richness for festivities of joy and those of black colour for mourning celebrations. In the latter, around the catafalque or capelardente, large pieces of paper with emblems were displayed, typical of a symbolic culture, in which many could not read, but could exercise their imagination and acuity in trying to decipher their contents.

The feast of the patron saint of the church, known from the first decades of the 17th century until 1946 as the Virgen del Sagrario, as well as her octave, was celebrated with special pomp and magnificence and the bishops used to give some jewel, or embroidered cloaks in Lyon or Barcelona, for her trousseau. The ceremonial for the aforementioned octave prescribes: "The mass of the octave is celebrated with special pomp and magnificence.The mass of the octave is sung with music. The afternoon procession starts after Vespers, Compline and rosary (which are followed, starting at three o'clock and average). In the main chapel a carol is sung; the procession through the naves takes place; after the choir another carol is sung and two in the cloister; on the way back to the cathedral the Salve is sung and with this the octave ends".

Fermín de Lubián, prior in the middle decades of the 18th century, had much to do with the enrichment of the Virgin of the Tabernacle's trousseau, with the commissioning of the gold and emerald crowns (1736) and the silver cabinet enriched with reliefs from Peru, a gift from the Marquis of Castelfuerte, and mirrors brought from Holland (1737).

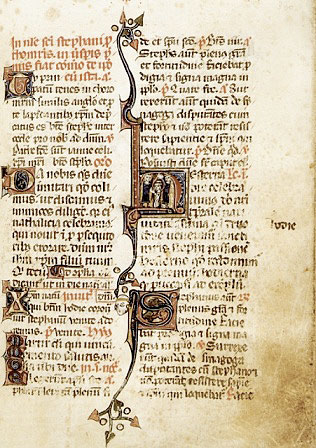

Page from the Breviary of 1332 from the time of Bishop Barbarán.

Relief of the Slaughter of the Holy Innocents on the altarpiece of Santa Catalina

Procession of San Fermin in 1923

Procession of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in 1925