April 20, 2011

Course

THE CATHEDRAL OF PAMPLONA. A VIEW FROM THE 21ST CENTURY

Interventions in the Cathedral between 1940 and 1946

D. Ricardo Fernández Gracia.

Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

The configuration of the interior space of the cathedral today is largely affected by the consequences of the intervention carried out in the post-war period, between 1940 and 1941, when it was decided to remove the choir from the central nave and the altarpiece from the presbytery, thus creating a historical faux pas with the placement of the choir stalls in the chancel and the location of the presbytery at plenary session of the Executive Council Wayside Cross of the Gothic nave.

Among the causes that led to that intervention that today we judge more than debatable are some distant in time and others closer. Among the first are some of the actions of Bishop Juan Lorenzo Irigoyen y Dutari (1768-1778), such as his desire to enlarge the main chapel or his refusal to give the blessing from his chair in the choir. Shortly after his death, the aesthetics of Academicism would arrive with the construction of the façade and the intervention of Ventura Rodríguez and Santos Ángel de Ochandátegui. At the end of the project, the latter proposed to the chapter the suppression of the choir and other minor reforms that, for the time being, were left in the file, but in no way forgotten. Everything that Ochandátegui proposed was in harmony with what he proposed in the Reflections on the Architecture, Ornament and Music in the Temple (Madrid, 1785), the work of Don Gaspar de Molina y Saldívar, Marquis of Ureña, architect, engineer, painter, poet and traveler of the Enlightenment from Cadiz.

The proximate causes must be linked to the liturgical movement of the central decades of the 20th century and to the tendencies of restoration in style that were imposed after the civil war. Of a first project commissioned by Bishop Tomás Muñiz Pablos (1928-1935) to the architect Francisco Iñiguez, we hardly know of its existence. The plans of the cathedral's beneficiary Onofre Larumbe, seconded by many others, led Bishop Marcelino Olaechea to take the matter into his own hands, delegating everything to him and his secretary Santos Beguiristáin.

Regarding the airs of liturgical renewal, we must cite the book by Bishop Manuel González García Art and Liturgy which went through several editions since 1932. His ideas are a clear exponent of the artistic-liturgical renewal of Spain in the first third of the 20th century. The sentences dedicated to the choirs of our cathedrals, as well as to the major altarpieces in a chapter entitled "Of the conceit of Art over the art of the altarpieces".Of the conceit of Art on the Altar.". Many of the paragraphs of this publication seem to be directly related to the performances in the Pamplona cathedral. In addition to what Gonzalez Garcia has said, we must add the proposals of Larumbe and the Benedictine Father Andreu Ripol, from the Abbey of Montserrat, who corresponded with Bishop Olaechea. This monk, who had been trained in Germany, specialized in liturgy and was the manager of the remodeling of the aforementioned Catalan abbey.

As for the trends of intervention in buildings in those years among architects, there are two main currents. The first "restorerThe first was the "restorationist" trend, the majority and following the work of Vicente Lampérez, was in favor of restorations in style. The second, more in tune with the new trends, was the so-called "conservative" one.conservative"headed by Leopoldo Torres Balbás. After the Civil War, the supporters of restorations in style gained positions.

The intervention was not free of tensions with those in charge of Fine Arts in Madrid, since both Don Manuel Chamoso and Don Francisco Iñiguez exchanged letters with the Bishop of Pamplona, whose content makes clear the disagreements and the criterion of Chamoso and Iñiguez against removing the altarpiece and eliminating the stalls from their place. The mediation of the Marquis of Lozoya, the proposal so that Yárnoz would become position of the works, together with the transfer of competences of the General Administration to the Institución Príncipe de Viana made possible the end with certain calm of the works, accepting the canons and the bishop the placement of the second order the choir stalls in the presbytery, since the set had been dismembered, being placed in other cathedral dependencies.

The works were received with the praise of the newspapers of the city. Thus it was expressed in Diario de Navarra, on April 9, 1940, praising some works tending to "highlight the beauty of the temple and will leave to the sight its splendid reality, its slenderness and gallantry, because in the first place it will be free of its present choir, unsightly, strange bulkhead to its factory and, in second term, because the disappearance of these three tawdry partitions ..."..".

The works were carried out without a general project , rather on the contrary, the criteria changed from day to day, but always in the interest of extolling the medieval part of the temple, even at the cost of all its decoration and leaving the interior of the cathedral as a devastated church or where it seemed to have passed the revolutionary troops in France in the late eighteenth century. Some photographs, before the neo-Gothic baldachin was placed in 1946, show the starkness of the cathedral's interior.

With the current criteria for intervention, we can only regret that true persecution of elements so typical of Hispanic cathedrals, such as the altarpiece and the choir. We cannot but remember that from the point of view of the different sensibilities of action and restoration of cathedral complexes, what happened in the Pamplona cathedral was not done with the rigor demanded by the monument, in its double vision of historical and artistic work. From the historical point of view, because it did not respect all the transformations of so many centuries, losing the authenticity and identity of the historical document -unicum- of the monument, and from the artistic point of view, because the result does not coincide, far from it, with the original plans of the building, neither from the formal, expressive or sensitive point of view. To all this we must add the lack of a clear plan of intervention in the whole, something that was already noted in the same year of 1940, to see how the sets were dismantled, without order or concert and absolutely everything was improvised, without a single coherent and technical direction.

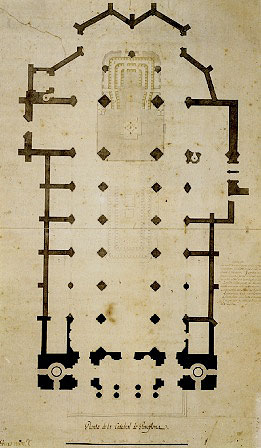

Ochandátegui's plan for the interior renovation of the Pamplona Cathedral in 1800.

Transchorus of the Cathedral of Pamplona before the intervention of 1940

View of the choir grille from the presbytery before the 1940 intervention.

Disappeared altarpiece of San Martín. Pamplona Cathedral

Dismantling of the choir grille of Pamplona Cathedral