15 February 2012

Global Seminars & Invited Speaker Series

PAMPLONA AND SAN SATURNINO

The burgh of San Cernin in the Middle Ages average

Mr. José Luis Molins Mugueta.

Chairof Navarrese Heritage and Art

In the early years of the 11th century, Pamplona was considerably depopulated. Sancho III el Mayor encouraged the revival of the city, which at that time consisted only of its original nucleus - later called Navarrería - the historical heir of the old Roman city. A typical episcopal see, it was inhabited by farmers and dependents of the cathedral, around which the hamlet was huddled. Around the years 1090 and 1100, an intense repopulation movement was recorded. The Burgo de San Cernin was born, on the plain on the side facing Barañain, which was populated by craftsmen and Frankish merchants. Almost simultaneously, the town of San Nicolás arose, although the Burgo always claimed greater seniority over it. In this process it is necessary to consider the figure of Bishop Pedro de Roda, also known as Pedro de Anduque or Pedro de Rodez, at the head of the Pamplona diocese between 1083 and 1115. Cultured, pious and dynamic, he was the promoter of the Romanesque cathedral, reformer of the chapter and introducer of the Roman rite in the liturgy. A devotee of Saint Saturnin (in 1096 he assisted Pope Urban II at the consecration of the basilica of Saint-Cernin in Toulouse), he donated to the Toulouse chapter the small church that existed in Artajona under the name of that saint at the time. During the pontificate of Bishop Pedro in Pamplona, his repopulating work is documented, both in Navarrería and in the Burgo and Población. The human and social reality precedes its legal regulation; and thus, the Frankish settlers who, at the end of the 11th century, were in fact settling on the plain to the west of the cathedral's urban centre, obtained the regional law de Jaca from King Alfonso I in 1129, which granted them numerous rights. From an urban planning point of view, the plan of the Burgo de San Cernin has several aspects to consider; firstly, the clear differentiation between it and both the old Episcopal City and the new town of San Nicolás, as shown by programs of study by J.M. Lacarra, J. Caro Baroja and J.J. Martinena. The layout of the former is articulated with reference letter to two main, perpendicular roads - the kardo and the decumanus - typical of Roman foundations. The plan of the town of San Nicolás, for its part, is in line with the known bastides, within the Aquitaine-Pyrenean series, and even anticipates later English models.

regional law del Burgo granted by Alfonso el Batallador in 1129.

(Pseudo-original from the 13th century. file Municipal Pamplona)

As far as the Burgh is concerned, the plan is adapted to a preconceived container, with a hexagonal layout, which encloses the layout of the streets, and which seems to respond to a plastic and symbolic image, in the way Vitruvius, for example, conceived the plan, in his case octagonal, adjusted to the compass rose. The plan of the burgh corresponds to a conception of an ideal city, which we could call Romanesque. Powerfully fortified - in some sections with a double wall, attested in recent excavations - its main axis (the main street of the Cambios, in reality a section of the pre-existing Camino de Santiago) culminates at the ends with two powerful defensive towers: the Galea, next to the Portalapea and close to the church of San Saturnino; and that of San Llorent, next to the parish church of San Lorenzo. The walled character of the Burgo is evident in the waxy representation of its documentary seal, which includes the characteristic average moon and star, within a defensive circuit, represented by four towers.

Waxy seal of the Burgo de San Cernin. Document dated 1294

(file Municipal de Pamplona)

Los habitantes del Burgo fueron gentes francesas procedentes de la ciudad de Cahors, expulsados por el rey capeto Felipe I, al decir del Príncipe de Viana. Sus ocupaciones fueron las propias de artesanos, mercaderes y cambistas. Estos cambistas extendían sus actividades comerciales más allá de las fronteras del Reino, acumulando grandes fortunas con el consiguiente acopio de poder político. Los artesanos potenciaron en hora temprana los gremios profesionales. Todos se mostraban impermeables a la penetración de personas de diferente condición social, fueran villanos, nobles, clérigos o simplemente navarros. Aunque, dada la escasez de brazos para las tareas del campo, mediado o a finales del siglo XIII acordaron traer a su barrio elemento labrador. Para cobijar a estos labradores determinaron la construcción de viviendas en la Pobla Nova del Mercat, área hoy día ocupada por el convento de Carmelitas Descalzos y por la plaza de de Virgen de la O, que se venía usando como mercado público. Esta presencia de indígenas navarros determinaría la construcción de la primitiva iglesia gótica de San Lorenzo, para su atención espiritual. A J. Carrasco se deben estudios sobre la población navarra en la Edad Media. En su investigación acredita que en 1366 había un total de 452 fuegos en el Burgo de San Cernin; 350 en la Población de San Nicolas; y 166 en la Navarrería. De los 918 fuegos u hogares de la conurbación pamplonesa (convengamos unos 4.590 habitantes) casi la mitad corresponden al Burgo y una quinta parte a la Navarrería, lo que certifica la manifiesta inferioridad de la Ciudad, a pesar de sus títulos históricos. Esta superioridad absoluta del Burgo en número de habitantes se mantendrá a lo largo del tiempo, con los altibajos debidos a enfermedades, guerras y circunstancias varias, que, por lo demás, también afectaron a los otros núcleos poblacionales. Desde el principio en el Burgo fue tomando auge un cuerpo de notables, los bons omes, representación genuina del vecindario. Para la administración y gobierno del incipiente municipio se estableció una corporación conformada por doce jurados (iurati o iuratz) elegidos de entre aquellos bons omes, para desempeñar el cargo durante un año. El procedimiento de acceso era la cooptación; es decir, que los cesantes elegían a los nuevos, en un panorama de monopolio de poder por parte de un círculo de familias. Contaban con Casa de Jureria para las reuniones. El alcalde administraba justicia y el amirat (almirante) la ejecutaba; ambos era funcionarios dependientes del obispo, su señor. De los intereses económicos del rey y del obispo se ocupaban claveros o bailes. Hace unos años la publicación, por A.J. Martín Duque, de unas cuentas correspondientes al año 1244 reveló interesantes aspectos de la sociedad y administración del Burgo. Se trata de la contabilidad correspondiente al final de un ejercicio anual, que los jurados salientes presentan a los entrantes para su aprobación. Por su temprana fecha, en Europa sólo es comparable a un documento similar relativo a Tournai, en el periodo 1240-1243. Con frecuencia los burgueses redactan sus documentos en lengua occitana, que es una koiné romance utilizada al sur del Loira y presente en ambas vertientes del Pirineo, sobre todo en los siglos XI, XII y XIII. En el último cuarto del siglo XII ya funcionaba una administración escrita de los asuntos de interés común. Un diploma datado en agosto de 1180 y conservado en el Archivo Municipal de Pamplona alude a la carta burgensium, especie de registro de los pobladores de San Cernin, con expresión de sus derechos de ciudadanía, plenos o restringidos. El mismo documento recoge la relación de profesiones vetadas por los del Burgo a los que no fueran de su mismo origen franco. Conocido es el panorama de conflictividad y guerra que presenta la relación de los núcleos poblacionales pamploneses a lo largo de la Edad Media. Cada una de las entidades se constituyó en municipio con personalidad propia, con sus concejos y jurados, su alcalde -con funciones judiciales- y el oficial representante del obispo, señor de la ciudad, que en el Burgo y en la Población se denominaba amirat y en la Navarrería, preboste. Las tres se encuentran potentemente fortificadas y la convivencia cotidiana se hace difícil entre sus habitantes, máxime teniendo en cuenta su distinto estatus jurídico, sus diferencias socio-económicas y el diverso origen étnico (franco, en el Burgo; indígena, en la Navarrería; y mixto, en la Población). Factores a los que deben sumarse las prerrogativas de que gozaba el Burgo y la paulatina debilitación de la autoridad episcopal, que se corresponde con el aumento del poder regio. Como piedras de la discordia sobre las que se armó el tinglado secular de odios, incendios y pleitos, dos cuestiones: en primer lugar, la tierra de nadie, comprendida entre el muro viejo de Santa Cecilia, en la Navarrería, y la barbacana del Burgo, terreno otorgado a la Ciudad por Sancho el Sabio en 1189. Y segundo, la disposición contenida en el documento del Batallador (interpolada o no, pero siempre invocada por los burgueses y por tanto, eficazmente negativa para la paz social) que dice: Et nullos homines de altera populatione non faciant murum, neque turrim, neque fortalezam aliquam contra ista populatione; y en caso de que la hagan, manda que los burgueses non dimitant illos facere, sino que resisant quantum potuerint. Las bases del conflicto estaban servidas: a enfrentamientos, choques y tensiones suceden treguas precarias. En 1222 la lucha cruenta del Burgo contra la Población y la Ciudad culmina con el incendio de la primera y la quema de su iglesia de San Nicolás, con la muerte de muchos inocentes en su interior. Se siguen disposiciones reales no siempre acertadas y ni siquiera imparciales. En 1266 la Navarrería y los tres burgos (en ese momento a los de San Cernin y San Nicolás hay que sumar el de San Miguel, de breve trayectoria histórica) se comprometen a vivir en paz y armonia, concordia que resultó anulada en 1274 por Enrique I. En 1276 los de la Navarrería, acicateados por el obispo, el cabildo y algunos nobles, se declararon en rebeldía contra la reina Juana, negándose a aceptar la sucesión de la dinastía capeta sobre el trono navarro. El Burgo y la Población se unieron contra ellos y el gobernador hizo venir un ejército francés que arrasó la Navarrería y con ella, el Burgo de San Miguel y la Judería. La destrucción fue de tal magnitud que durante los cuarenta años siguientes se pudo sembrar y recoger trigo en lo que habían sido calles y solares de casas. Tan sólo se salvó la catedral y sus construcciones anexas, pagando el precio de un bárbaro saqueo. De aquellos sucesos queda como crónica el relato, en verso occitano, de Guillaume Anelier de Toulouse, titulado Histoire de la guerre de la Navarre en 1276 et 1277.

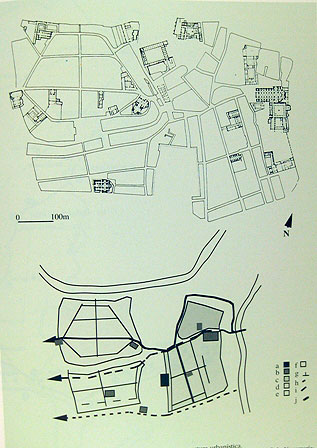

El Burgo, the Navarrería and the town of San Nicolás, according to Jean Passini.

(In black, the Calle Mayor -de los Cambios-, coinciding with the Pilgrims' Road to Santiago)

Once Navarrería had been destroyed, in 1287 the people of El Burgo and La Poblacion joined together to form a single municipality and tried to claim the title of degree scroll de Ciudad, a claim that was contested by the mitre. In 1308, the ruin persisted and Luis el Hutin authorised the stonemasons to take the stone from the razed Navarrería to use it in the Building of the castle that was being built at that time in the Chapitel meadow. In 1319, Bishop Arnalt de Barbazán ceded the domain of the city to King Felipe el Luengo, with all the inherent economic rights, in exchange for a compensatory rent in money and the retention of some properties. The king undertook to rebuild the Navarrería and work began immediately, including the occupation of the previously controversial land located between Santa Cecilia and the Burgo de San Cernin. In 1324, Charles the Bald granted the privilege of repopulation, establishing the census contributions of the inhabitants, by streets and in three categories. The enclosure of the Navarrería behind a strong wall was authorised, a work that was completed late in the 14th century. In the current area of Calle de la Merced and place de Santa María la Real, the Jewish Quarter was rebuilt, with its synagogue. Although the Burgo and the Población continued to be united, there was no shortage of continuous lawsuits, a long list of which would be too long here. In 1422, on the occasion of the Prince of Viana's visit to Pamplona at visit , serious disputes arose between the three towns over issues of pre-eminence and protocol, which led King Carlos III the Noble to unify Navarrería, together with the Burgo and San Nicolás, into a single town, a single town council and a single district and jurisdiction. To this end, he agreed with the Cortes that the old entities should appoint procurators to debate the matter. This is how the Privilege of the Union was agreed, sanctioned and promulgated by Charles III on 8 September 1423, on the Marian feast of the Nativity of the Virgin. This document legally overcame the previous dissensions and established the instructions of neighbourly harmony, so often broken by fratricidal hatred in previous centuries. In it, the internal organisation of the new Most Noble City is minutely specified, to which the common legal status of regional law General is assigned; and it is granted a coat of arms, a silver lion passing over a field of azure, surmounted by a royal crown and surrounded by the chains of Navarre, signifying that Pamplona and its Cathedral of Santa María are the place determined for the coronation of the kings. The new City will have a single mayor or ordinary judge and a single justice, even replacing the former admirals and provost in the name. The system envisaged was an efficient code for its functioning until 1836. The demographic and social importance of the old Burgo de San Saturnino was recognised in the Privilege. Of the ten juries provided for in the new statute of the unified municipality, five correspond to its district (three to San Nicolas and two to Navarrería). The alderman corporal of the Burgo would preside over the sessions, sit as the pre-eminent cap de banc and head the ceremonial acts in a distinguished place, except for the mayor's attendance . The construction of the Casa de Juraría or Consistorial on no man's land, in the middle of the three towns, symbolises the unifying spirit of the document. The creation of bonds of friendship, family or interest and urban unification will be a matter of time.