February 1, 2012

Global Seminars & Invited Speaker Series

PAMPLONA AND SAN SATURNINO

The vow of 1611 and the festival to the present day

D. Ricardo Fernández Gracia.

Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

The vote of the Pamplona Regiment in 1611, in the close context of the clashes between Xavierists and Ferminists, had as a consequence the elevation of San Saturnino to the rank of patron saint of the city. This was recognized by the municipal written sources and the bishop, very soon, just a few decades later, in 1626 and 1644. An official celebration with a protocol that, in essence, has been preserved to the present day, although it has been reduced in recent times as regards the eve and the preliminaries of the procession of the feast day. Otherwise, the gist of what was stipulated in 1611 by the Regiment of the city continues: "it has been agreed that on his day every year a solemn procession be made from the said cathedral to his church and that in it, his Lordship of the said chapter say mass with sermon, naming the said Regiment preacher for this, as is done in the other feasts of his vow and devotion; and that on the eve bonfires be made throughout the said city and other demonstrations of contentment, summoning to the divine offices all the people so that in their prayers they pray...".

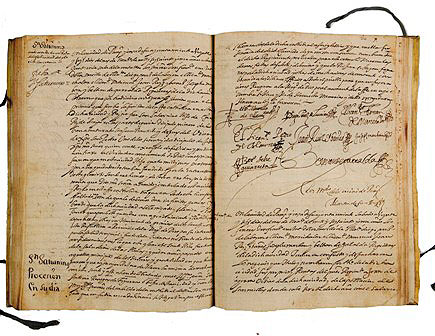

Vow of the City of Pamplona to St. Saturnino

November 26, 1611

file Municipality of Pamplona

Along with the official festivity around religious cults and ceremonies, the parish of San Cernin and its Obrería -species of board management assistant chosen among the inhabitants of the neighborhoods of the burgh- prepared, throughout the past centuries, some recreational entertainments, fundamentally fireworks, music and oxen and bulls to run the eve and the day of the saint in the surroundings of the temple. Later, in plenary session of the Executive Council XIX century, from the Teatro Principal and other entities would be celebrated with outstanding theatrical performances or zarzuela.

In the secular celebration by the people of Pamplona, everything related to relics, hagiography and iconography of the saint played an extraordinary role. The cult of the relics of San Cernin, the tradition of the most real and legendary San Saturnino in the imagination of Pamplona, together with outstanding painted, sculpted and engraved images, have historically constituted a reference point for the identity of the city.

Two important cycles on the life of San Saturnino are preserved in Navarra. The first one is painted in the church of El Cerco de Artajona, and the second one is on the strips of the cloak of San Cernin that, year after year, has been used from the end of the 16th century to the present day in parish liturgical celebrations such as the vespers attended by the councils of the parishes of San Lorenzo and San Nicolás until the 19th century.

Pluvial layer of the terno de San Saturnino. Miguel de Sarasa. 1584

Parish of San Saturnino of Pamplona.

The iconography of San Cernin was visualized in different images, made in polychrome wood and silver or engraved on paper. In many cases the saint, accompanied by the bull that led him to martyrdom, appears with other signs of identity of the city such as the Virgen del Camino, San Fermin and even San Francisco Javier, or the very heraldic emblems of Pamplona and the Kingdom of Navarre.

Regarding the transmission of the history of the saint, we must mention in Pamplona, in addition to the famous Codex of San Saturnino that collects the liturgical official document and the versions of his life and martyrdom, the monographs of authors such as graduate Andueza (1607), Juan Joaquín Berdún (1693), the famous conference proceedings Sinceras de Miguel José de Maceda (1798) as well as the sermons preached by panegyrists nominated by the Regiment of the city, some of which were published, generally in the presses of the publishers of the capital of Navarre.

Regarding all those images, it must be remembered that they were extraordinarily effective in moments of scarcity of the same, in which the time for their contemplation was abundant, so that whoever looked at them could extract different sensations and valuations. In final and as David Freedberg has masterfully written, comparing past times with the present, we no longer have "enough leisure to contemplate the images that are before our eyes, but once people did look at them; and they made contemplation something useful, therapeutic, that elevated their spirit, gave them comfort and inspired fear. All in order to reach a state of empathy".