February 29, 2012

Global Seminars & Invited Speaker Series

PAMPLONA AND SAN SATURNINO

Festive echoes in the Navarrese press

Mr. José Javier Azanza López.

Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

The content of this intervention focuses on the first third of the twentieth century, a period in which the presence of the feast of San Saturnino is concretized both in the daily press -The Echo of Navarre, The Tradition of Navarre, El Pensamiento Navarro, y Diario de Navarra-as well as in the illustrated magazines published fortnightly or monthly, as in the case of La Avalancha.

In the case of the daily press of Navarre, we must point out that the feast of San Saturnino assumed a greater informative protagonism with the passing of time, going from a brief "gazette" camouflaged among the rest of the news in the inside pages, to become already in the twenties the main front page headline, accompanied by abundant graphic material captured by the photographers Roldán and Galle. An event is core topic in this evolution, as it is the fact that in 1920, the festivity was made to coincide with the laying of the first stone of the new Ensanche of Pamplona, a circumstance that caused the front page of the newspapers to give extensive news, both of the religious function, as of the subsequent ceremony of laying the first stone.

Cover of Diario de Navarra, November 30, 1927.

Once this progressive informative protagonism is known, we must dwell on its content, which includes both the official acts programmed by the institutions, as well as the entertainments that accompanied the festive day.

The main event was the religious function organized by the City Council and held in the parish church of San Saturnino. At a quarter to ten o'clock, the municipal corporation, preceded by the brass, bugles and timpani, went to the Cathedral to pick up the council and go to the church of San Saturnino, from where the public procession with the image of the saint started. The parish cross and the flag of the city opened the march, and the procession included the town councils and religious communities, the schoolchildren of seminar Conciliar, the residents of the Casa de Misericordia, and the City Council presided over by the mayor, who was occasionally accompanied by the civil governor; the procession was closed by the music band of the Regimiento de la Constitución (from 1920 La Pamplonesa, created a year earlier, will do so), escorted by a military picket.

The primitive pathway agreed in 1626, which included the streets Mayor, Taconera, San Antón, Zapatería, Calceteros, Chapitela, Mercaderes, place de la Fruta and San Saturnino, will be modified from 1916, to shorten by Eslava Street, place de San Francisco and San Miguel Street. But regardless of the route, the large number of people and the presence of hangings that adorned the facades of the houses remained as constants. In case of rain the procession was suspended, limiting itself to cross the interior naves of the temple.

Once the procession was over, the Cathedral Chapter and the City Council took their seats to the right and left of the main altar, and the Pontifical Mass was celebrated by the bishop of the diocese. The Cathedral chapel was in charge of the musical part, interpreting the masses of Eslava or Perosi, while the sermon was delivered by eloquent sacred orators; the journalistic chronicles do not forget to mention their identity and detail the content of their homily.

Around twelve o'clock and average the act ended, after which the City Council accompanied the cathedral chapter in procession to its church, to then return to the Town Hall. In the reception hall of the latter took place at noon another of the official events, the banquet that brought together the municipal corporation and often joined by the civil governor, in which diners were given a succulent menu served by renowned restaurants such as Casa Marceliano, the Grand Hotel, the Maisonnave, the society of Mr. Matossi and Co. (owners of the Café Suizo), or the Hotel Quintana.

As it was a public holiday, Pamplona was very lively, and there was a wide range of amusements and entertainments, for all audiences and for all budgets. Among the most popular events were the rides. As long as it did not rain, both the gardens of the Taconera and the surroundings of the city were crowded with people from Pamplona who took advantage of the central hours of the day to enjoy a stroll in the open air. The musical concerts held at the place de la Constitución on November 28th and 29th, both at noon and in the evening, were also very popular. On both dates there was also a zezenzusko or fire bull.

Sports competitions were not lacking either, especially the pelota matches that, for the benefit of the Casa de Misericordia, were held at the Euskal Jai fronton on San Agustín Street. The confrontations between Navarrese and Guipuzcoans aroused the interest of the people of Pamplona and San Sebastian. Soccer matches were also held, first in the fields of Punching, Ensanche and Hipódromo, and later in San Juan. Likewise, the theaters and cinemas of the city programmed special functions, which were very crowded, since in many occasions the weather was not good and the attendance to the theater or the cinema was a good solution to spend the festive afternoon.

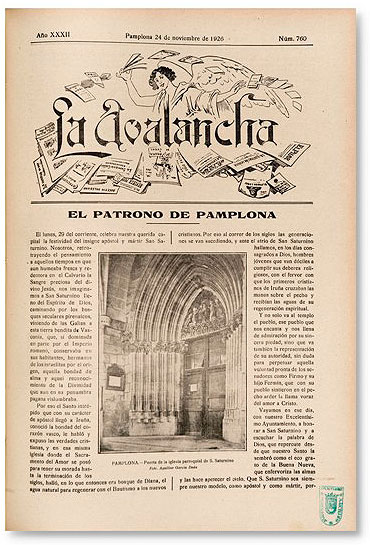

Front page of La Avalancha, 24-11-1926

Along with the daily press, other publications alluded to the festivity of San Saturnino, such as the illustrated fortnightly magazine La Avalancha. In this case, the content is very different from that of the daily newspapers, since its purpose was not to inform about the events programmed or already celebrated. It includes contributions of a theological-doctrinal nature.

Thus, there is no lack of a publishing house of the essay which by rule generally reflects three basic ideas: joy for the festivity ("He is neither a good Christian nor a good man from Pamplona who does not rejoice on the day of patron saint", we read in 1913); gratitude to the saint ("Let us thank the glorious Saint Saturninus for having taken us out of the degradation of paganism on his next feast day" states the publishing house of 1930); and the application of his help and protection ("May San Saturnino guard his beloved people of Pamplona, and defend them from all enemies class ", requests the 1912).

The pages of La Avalancha also include historical programs of study , religious-moral texts, fragments of sermons preached years ago, and poetic compositions in honor of the saint, signed by authors such as Máximo Ortabe and Baldomero Barón. The above contributions are accompanied by snapshots taken by a large number of amateur and professional photographers, including Fermín Istúriz, Julio Huici, Aquilino García Deán, Julio Cía, Roldán and Agustín Zaragüeta. These are photographs that only exceptionally illustrate the religious function, focusing instead on artistic aspects of the temple of San Saturnino, such as its portico, façade and towers, the main altarpiece, or the image and relics of the saint. Sometimes we also find photographs related to other buildings also related to the figure of San Saturnino, as in the case of the parish of San Saturnino de Artajona, or San Saturnino de Toulouse.