17 October 2012

Global Seminars & Invited Speaker Series

AROUND THE EXHIBITION OCCIDENS. DISCOVER THE ORIGINS

The Renaissance and Baroque Centuries: Art, festivities and power

D. Ricardo Fernández Gracia

Chairof Navarrese Heritage and Art

The Gothic cathedral of Pamplona, like other temples of its category, was enriched throughout the centuries of the Ancien Régime with important sets of dependencies, altarpieces, stained glass windows, hangings and other pieces of liturgical furnishings, such as pulpits, choir stalls and organs. The interior space of the church was shaped shortly after its completion, around 1501, with the commissioning of a magnificent choir stalls for the choir (1539-1541), designed to be placed in the central nave, as well as with the main altarpiece at the end of the century (1597) in the main chapel. Although in the middle of the following century some altarpieces were made for the chapel of Bishop Prudencio de Sandoval and for the Barbazana chapel, it would be in the last years of the 17th century when the interior of the Gothic naves was baroque, with the construction of internship totality of its altarpieces in accordance with the prevailing decorative and traditional style. The walls of the chapels and ambulatory were enlivened by the rich gold of the masonry of large wooden architectures. If in the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela there was a canon manager of the transformation of its interior in the second half of the 17th century, the well-known Don José de Vega y Berdugo, in the capital of Navarre, we also find a prebendary who played a similar role, specifically Don Diego Echarren, who, as we shall see, occupied the priory between 1682 and 1707. The prior's example was followed by other canons and dignitaries, as well as some confraternities and the chapter itself. To the altarpieces should be added the rich collections of hangings with which the few stone walls that remained clean were draped for the many festivities of the year, in keeping with the different liturgical moments of the year.

The eighteenth century would be marked above all by the construction and renovation of a large part of its rooms, highlighting the chapter house conference room , the renovation of the sacristy and the construction of the impressive Library Services.

All this plan of works was closely related to the Catholic Reformation and certain cults to the Eucharist, to the Virgin and to the new models of sanctity, and took on a special significance in certain ordinary and extraordinary moments, on the occasion of liturgical feasts, or linked to the city and the Kingdom.

As far as the feasts were concerned, the novelties were also to be noticed with the new times of the Counter-Reformation, in which the needs were different and the models of sanctity were different as well. Between 1605 and 1643, the day of the Guardian Angel was a feast of obligation, by episcopal disposition. Later would come the lawsuit of the co-patronage between the supporters of San Francisco Javier and San Fermín. The Pamplona seo together with the regiment of the city were the standard bearers of the cause of San Fermín, until the Brief of Alexander VII that declared both patroni aeque principals, in 1657.

Events of a religious nature, but also linked to the Hispanic monarchy, took place inside the cathedral. Oaths of princes, proclamations, funerals and prayers for different reasons, requested by the Habsburgs and Bourbons, were celebrated in the first diocesan temple. Among the great religious festivities we must mention the ratification of the board of trustees of San Francisco Javier by the Cortes in 1624 and the immaculist vote of the institutions of the kingdom in 1621, as well as countless rogations with the images of San Fermín or the Virgen del Sagrario requested by the city council and organized by the chapter, not without friction, disagreements with other civil and ecclesiastical institutions and frequent lawsuits for preferences and precedence, so usual in the society of the Ancien Régime.

All these festivities were surrounded by an unparalleled rhetorical apparatus. The interior of the temple was "hung", that is, it was covered with hangings, tapestries and pastries appropriate to the reason for the celebration, reserving those of greater pomp and richness for festivities of joy and those of black colour for mourning celebrations. In the latter, around the catafalque or capelardente, large pieces of paper with emblems were displayed, typical of a symbolic culture, in which many could not read, but could exercise their imagination and acuity in trying to decipher their contents.

As is well known, every festival, including religious festivals, is a dynamic phenomenon: its traditions are maintained, lost, reappear or are created over the years. Within it, continuous changes take place, and it has a connection with the past and with the future. In general, and apparently, festivals have become more secularized and more playful, spectacular and less ritualistic.

This begins with the creation of the first man and continues in the four capitals representing various episodes of Genesis up to the Tower of Babel, whose construction presents an image of everyday life. The topic of Job, a prefiguration of the Passion of Christ, in two other capitals, allows us to link the Old Testament with the cycle of the Passion represented in the doors of the Refectory - which includes a program of Eucharistic exaltation - and of the Archdeaconry in the southwest corner. Exceptional iconographic interest offers the Door of the Amparo that represents the Koimesis in the tympanum and a beautiful image of the Virgin and Child in the mullion, both crowned, and accompanied by other scenes, among them an Annunciation and the episode of the fall of Adam and Eve, that served to the medieval theologians to explain the reasons for this singular Marian privilege. Finally, the last great doorway of the cloister, called the Precious Door, on the southern side, develops the cycle of the death and Coronation of the Virgin. Undoubtedly the repetition of the psalm: "pretiosa est in conspectu Domini, mors sanctorum eius" that accompanied the reading of the Pretiosa or the martyrology that the canons of the Cathedral made daily in the chapterhouse conference room , whose door they had to cross to access it, could have motivated its iconographic program. This would also explain the series of martyrdoms of saints represented in the keystones of the vaults of the adjoining sections. Another devotion that the chapter had to fulfill, according to the bishops' decree, was the nocturnal procession after Compline from the choir to the chapel of Jesus Christ, which included, among others, two seasonal stops in the cloister, one before the group of the Epiphany in the northeast corner and another before the effigies of St. Peter and St. Paul located at the door of the Barbazana chapel. The documents of the Cathedral have allowed us to know the antiphons and prayers that the canons prayed before these images.

Festive acclamations and joyful demonstrations made by the Most Noble and Most Loyal City of Pamplona, head of the Kingdom of Navarre, on the entrance of Our Lady Doña Mariana de Neoburg, Pamplona, 1738

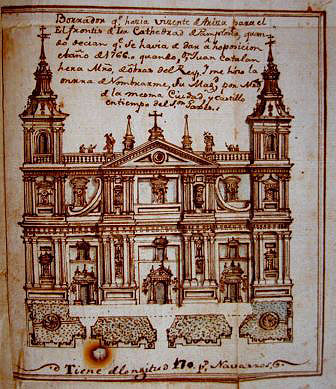

project for the facade of the cathedral of Pamplona by the master builder Vicente de Arizu. 1766.