29 October 2013

Global Seminars & Invited Speaker Series

Diego Díaz del Valle: a painter from Cascante in the Age of Enlightenment

D. Ricardo Fernández Gracia.

Chairof Navarrese Heritage and Art

Diego Millán Díaz del Valle was born in Cascante in 1740, the son of Ignacio Díaz del Valle, also a painter from Vitoria, and his second wife, Teresa Condón Falces, from Cascante, whom he had remarried in 1739. Ignacio worked for the shrine of El Romero and for the town council of Cascante when Diego was a child.

Diego married very young, at the age of eighteen, in 1758, to a woman from Huarte-Pamplona called María Francisca Ardáiz Anocíbar. The marriage produced at least two daughters named María Joaquina and Tadea. In 1803 he was widowed and married María Teresa de Etorralde y Organvidea, a native of Ordax, two years later, in 1805, and was recorded in the corresponding register as a "painting teacher". He died in 1817 in Viana, according to Altadill.

Díaz del Valle's artistic personality is discreet but truly overflowing in terms of his geographical dispersion throughout the whole of Navarre. The reason is undoubtedly to be found in the fact that he was the only easel painter based in Navarre during the last third of the 18th century. From his native Cascante he worked for the Franciscans of Olite, the collegiate church of Borja, the basilica of the Immaculate Conception in Cintruénigo, the convent of the Discalced Carmelites of Araceli in Corella, the monastery of Fitero and numerous parishes in Navarre, Argonès and La Rioja. The parish church of La Asunción in Liédena houses his last work, a canvas of Saint Bartholomew executed in 1817, when he was 76 years old.

Diego Díaz del Valle

Pope Nicholas V finds the body of Saint Francis

Franciscan Convent of Olite

His paintings are not outstanding for their quality, although the exercise of his profession in the Age of Enlightenment, plenary session of the Executive Council, led him to read Vitruvius, Carducho and Alberti and to study the iconology of Cesare Ripa, as evidenced in some of the writings he left behind and published after his death.

In addition to easel painting with devotional images, he painted so-called perspective monuments, including the parish churches of Cintruénigo (1768) and the Assumption of Cascante, contracted in 1782, and the cathedral of Tudela, which served as modelfor the previous one. He also made positionof large groups of paintings in Olite, Fitero and other localities, with the group in the chapel of the Cristo de la Columna in Cascante (1798-1799), for which he gave an exhaustive explanation, standing out above all in this chapter. Of the rich collection of allegorical paintings described in his publication, only the two large canvases depicting the Arrest and the Ecce Homo have survived. In this respect, it should be noted that in its day, before most of the paintings were covered, it was one of the largest collections of allegorical paintings in the Autonomous Community of Navarre.

Diego Díaz del Valle

Portrait of Philip V

New sacristy. Tudela Cathedral

Apart from purely religious commissions, he also specialised in portrait galleries of dubious quality, such as the portrait of the kings of Navarre executed for the Pamplona town hall (1797), isolated royal portraits for the regiment of Tudela, The portrait of Charles III, signed in 1797, and seven canvases in the new sacristy of Tudela Cathedral (1783), in which various benefactors, kings, religious and intellectuals were depicted, whose actions raised the cathedral's status from collegiate to cathedral. There we find Campomanes, the best painting in the gallery, signed by Alejandro Carnicero, next to the work by Díaz del Valle: five kings, two from Navarre and three from Spain: Alfonso the Battler, liberator of the city from the Muslim yoke, Sancho the Strong, considered the patron of the material construction of the church, and Philip II, Philip V and Charles III, for their efforts to obtain the cathedral dignity for the church. A final canvas from 1797 depicts the first bishop of Tudela. Around the same time he painted a gallery of portraits, now lost, for the Marquis of San Adrián. At the beginning of the 19th century, in 1816, he painted a large portrait of the entire community of the Discalced Carmelite nuns of Araceli de Corella.

Diego Díaz del Valle

Portrait of Philip V

Pamplona Town Hall

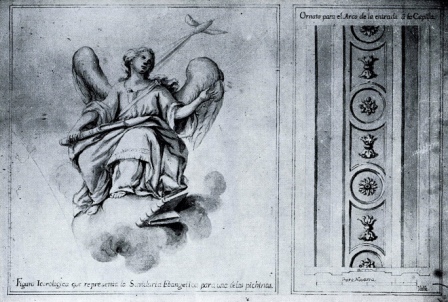

Díaz del Valle did not disdain the architectural design, as evidenced by some of the drawings published by José Luis Molins in connection with the remodelling of the chapel of San Fermín and others that are kept at the fileMunicipal de Pamplona for various parts of the interior of the City Hall. He also carried out some projects for neoclassical altarpieces and others for the remodelling of Baroque altarpieces, such as the one in the Collegiate Church of Borja, signed together with the Italian sculptor Santiago Marsili. Lastly, he also tackled other artistic commissions, such as devotional engravings, at subject.

Diego Díaz del Valle

designfor the chapel of San Fermín in Pamplona

Of his intellectual work and even his academic training, typical of a master of those times who called himself a professor of painting, we can see in the explanation he left written about the ensemble in which he expressed all his knowledge and understanding destined for the decoration of the chapel of the Cristo de la Columna in Cascante, in what we could call "the artist explains his work", where he states: "It is not possible for all those who come to see the preciousness invented by art in the primors of painting, to penetrate the ideas of a professor in the decoration of his works. The former must be appropriated to the subject or object of the latter, and the latter must be executed in a place proportionate to the appropriate expression of the former, as Vitruvius, the learned Leon Bautista Alberti and the famous Vicencio Carducho foresee. But what happens in this type of work? Executed by a professor with the greatest care, at the cost of pains and study, and with scrupulous attention to the rules of his School, the most idiots believe themselves authorised to judge of their proportion, of their propriety in ideas, of their taste in ornamentation, and not a few criticise them as they please: but few understand what they see, and almost all censure them at their own discretion. In the worthy weighing of those in this, I certainly reject as judges those who, with no other rule than their whims, their unchosen taste, and their no aptitudefor graduating the delicacies of a brush, deserve only contempt in their censures; and I wish only to attend to a simple idea of those which I have had in the arrangement of the decorations of the chapel of the Most Holy Christ of the Column, and of each of its parts, for the intelligence of those who, with a healthy and devout intention, wish to know what is the meaning of the various figures which adorn it.

Without this clear explanation they would register it without light: and without this light, not only would they not be able to raise their imagination to the figurative, but many would still conceive some ideas very Materials (so to speak) and alien to reason and faith".