6 March 2013

Global Seminars & Invited Speaker Series

STATELY AND PALATIAL ARCHITECTURE OF PAMPLONA

The Episcopal Palace of Pamplona

Mr. José Luis Molins Mugueta.

Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

Antecedentes históricos

La existencia documentalmente probada de la diócesis pamplonesa se remonta al año 589, fecha de celebración del tercer Concilio de Toledo, en que consta la presencia del obispo Liliolo -episcopus pampilonensis- como suscribiente de las actas. Es conocida la existencia de una primitiva catedral prerrománica, que resultó arrasada prácticamente en totalidad a consecuencia de las razzias musulmanas, especialmente la emprendida por Abderramán III en 924. A Sancho III el Mayor (1004-1035), en su etapa final de reinado, se debe la restauración de la diócesis, a la que seguirían, en sucesivos momentos de los siglos XI y XII, las construcciones de la seo y dependencias anexas románicas. Y así, más allá del claustro gótico, tras rebasar su puerta Preciosa, en el extremo sureste del conjunto catedralicio actual, se localiza hoy un pequeño templo y vestigios de la residencia episcopal aledaña: ambos, capilla y palacio románicos, fueron conocidos como de San Jesucristo.

En 1198 Sancho el Fuerte hizo donación al obispo don García Fernández del palacio de su propiedad, construido en torno a 1189 por su padre, Sancho VI el Sabio, y situado en un extremo de la Navarrería. Bajo la advocación de San Pedro, a lo largo de la Edad Media la titularidad del edificio, -ampliamente transformado hoy en sede del Archivo General de Navarra-, fue ocasión de litigios y tensiones entre la mitra y la corona, pasando sucesivamente de una a otra jurisdicción. En 1255 el obispo Ramírez de Gazólaz convino la entrega del palacio al patrimonio real, acuerdo anulado cuatro años más tarde por el papa Alejandro IV. Cuando en 1319 el obispado cedió el señorío temporal de la ciudad en favor de la monarquía, se reservó expresamente la posesión del inmueble y sus anejos. Esta circunstancia ocasionó presiones de los reyes Juana y Felipe de Evreux sobre el obispo Barbazán (1318-1355). Prosiguió la situación litigiosa hasta 1366, momento en que Carlos II restituyó el palacio al obispo Bernardo de Folcaut. Curiosamente los reyes no abandonaron el edificio, con lo que se dió una cohabitación de los titulares de las potestades religiosa y civil en el mismo palacio. Mediante las oportunas compensaciones convenidas entre partes, el palacio de la Navarrería pasó a la Corona en 1427, reinando doña Blanca, ya casada con Juan, infante de Aragón, más tarde Juan II. Con la anexión de Navarra a Castilla el palacio derivó en residencia del virrey; pero a fines del siglo XVI (1590) el obispo Rojas y Sandoval todavía reclamaba del rey la propiedad del edificio

Se tiene noticia de la existencia de una mansión episcopal, llamada Palacio de Jesús Nazareno, que estuvo situada en el arranque de la calle Compañía, acera de los impares, en la confluencia con el número 22 de Curia, en el solar que más tarde fue hospital de peregrinos, bajo advocación de Santa Catalina. Este palacio fue coetáneo del de San Pedro y necesario como residencia en los momentos litigiosos descritos. Resultó arrasado en 1276, con motivo de la Guerra de la Navarrería; aunque, según testimonio del cronista de Navarra P. Moret, mediado el siglo XVII la calle Compañía todavía era designada como Calle del Obispo, en su recuerdo. No lejos, en el actual número 29 de la calle Curia, estuvo situada la Torre del Obispo, como atestigua hoy en día un sótano gótico abovedado. Es parte de un edificio adquirido por don Bernardo de Folcaut en 1370. En 1427 don Lancelot, hijo natural de Carlos el Noble y Administrador Apostólico de la diócesis, se hizo habilitar la residencia palacial en una casa, entonces propiedad del Arcediano de la Cámara, que quizá fuera esta misma. En todo caso, los sótanos de la Torre del Obispo, que pudieron formar parte del palacio de don Lancelot, en el siglo XVI se convirtieron en mazmorras de la cárcel episcopal. En esta casa radicó además la Curia eclesiástica, circunstancia que determinó la denominación de la calle. En un proceso sobre habitación del obispo, iniciado en 1564 y seguido ante el Consejo Real (citado por J. Goñi Gaztambide), el canónigo hospitalero Pedro de Aguirre argumentaba en 1569 que los prelados de Pamplona tenían su casa propia, llamada la Torre episcopal, frente a la catedral. A ello replicaba el obispo, don Diego Ramírez Sedeño de Fuenleal, que “la Torre o casa que dicen del obispo cerca del cimiterio de la iglesia catedral (hoy, plazoleta ante su fachada) no es aposiento honesto ni bueno para que pueda caber ni vivir el dicho obispo en él”.

A partir de 1590, bajo el episcopado de Sandoval y Rojas, y hasta 1740, los obispos residieron a precario en la Casa del Condestable, situada en el arranque de la calle Mayor, que era propiedad del duque de Alba. Un edificio que también fue liberalmente franqueado al Ayuntamiento de Pamplona como sede, entre 1752 y 1760, mientras se construía una nueva casa consistorial.

Episcopal Palace of Pamplona. General view

Julio Cía, 1943

file Municipal of Pamplona (AMP)

The bull of appointment of the prelate Don Melchor Ángel Gutiérrez Vallejo, signed by Benedict XIII on March 28, 1729, put an end to the long and prolonged precariousness of accommodation. The pontifical document explicitly imposed on the bishop the obligation to build a new residency program. Gutiérrez Vallejo quickly undertook actions towards this end, some without success. On September 1, 1731, an agreement was formalized with the cathedral chapter and clergy of the diocese for the construction of a residential building, capable, in addition, of housing the court, the jail (then located in the Bishop's Tower), and the ecclesiastical file . The agreement, scrupulously documented by J. Goñi Gaztambide, considered the cost of the works, initially foreseen at 22,000 ducats, of which the chapter and clergy committed to contribute 14,000 in five years. To this contribution would be added the donation of the four parishes of Pamplona, plus those of Fuenterrabía, San Sebastián and Valdonsella, estimated at 4,200 pesos. The final cost exceeded 37,000 ducats and the bishop had to take measures on his own to meet the payment: sale of goods and dues, alienation of the Tower... The twenty-one chapters of the agreement provide interesting information data. The palace was to be built on the site of some houses owned by the Marquis of Cortes, which faced the street that separated them from the convent of La Merced. Adhering to the cabildo's orchard and on its enclosure, parallel to the tracks of the mallet game, a passageway could be built between the new building and the cathedral, on arches and columns, with certain limitations of use, height specifications and rights to enjoy the views, sun and air.

The upper corridor itself will belong to the palace. Conditions are stipulated for protocol when it is used by the bishop, depending on the nature of the function he presides over in the cathedral, pontifical or otherwise. It is determined that both the windows of the palace and the transit windows facing the orchard should be equipped with iron gates, which prevent them from going down to the land owned by the Chapter. In the period of vacant seat the custody of the palace will be skill of the chapter; and as much in full seat as in vacant seat, the custody of the file will be skill of the archivist. This agreement between bishop and chapter was approved by the pope on January 3, 1732 and ratified by Clement XII on June 14, 1734.

Episcopal Palace of Pamplona. Rear façade and orchard

On the left the transit to the cathedral

Julio Cía, 1933 (AMP)

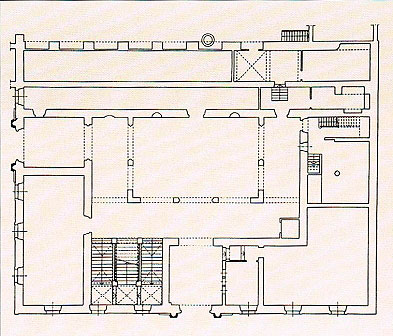

Episcopal Palace. Map

(Catalog Monumental of Navarra)

The building

Located in the place of Santa María la Real, practically Exempt from the urbanistic point of view and exposed to the inclemencies of the predominant north wind of Pamplona, the Episcopal palace forms a cubic block of four facades, of which three are very well cared for, two have sculptural doorways and one, the one that faces the orchard, is simpler. Coinciding with other baroque buildings in Pamplona and the area average, it combines ashlar stone, a building material typical of the Mountains of Navarre, and brick, characteristic of the Ribera, in a successful fusion and synthesis. Of riverside lineage -and linked to the architecture of the Ebro valley- is also the inclusion of the upper gallery of arches. In height, the two basal floors use stone; and the two upper floors, in addition to the arches, use brick. Horizontally, the separations are marked by platabandas. The openings are arranged typologically by levels: latticed windows on the two lower floors (with grilles on the bottom and protruding grilles on the top); balconies with finely molded stone steps on their fronts, with bars of grilles on the main floor; windows that have been cut to the size of balconies, with grille parapets on the fourth floor. Finally, a wide cornice, ornamented with dentils and molding, supports the gallery of arches that runs as a finial.

Archbishop's Palace of Pamplona. Amparo Castiella, 2013

Special consideration should be given to the two portals, which face the place of Santa María la Real and the small square shared with La Providencia. They follow a similar outline , designed totally or partially by Goyeneta, who conceived them in Roman Doric order (also called Tuscan), each one flanked by columns, seated on a plinth, with smooth shafts, although with a grooved imoscapo, supporting an entablature, in whose frieze metopes and triglyphs alternate. The opening of entrance is highlighted with a mixtilinear tracery. The space between the lintel, supported on mensulones, and the aforementioned entablature is decorated with plastic motifs of episcopal theme: a hat with twelve tassels, pectoral, mitre with infulas and crosier. Above it there is a niche, which at the back corresponds to a glazed window with a baroque vocation of transparency, whose niche houses a free statue of a bishop, dressed in his ornaments. Door and niche are ornamented with vegetal scrolls. It is usually considered that the two sculptures represent San Fermín, Patron Saint of the Pamplona diocese since an undetermined date and Co-Patron Saint of Navarre since 1657. But a careful observation leads us to partially qualify the assertion, because we will appreciate different age and condition. In today's main door, the bishop is represented young and beardless, within the iconographic tradition that contemplates Fermín as a young bishop and martyr. The other statue depicts an elderly bishop with an abundant beard, who could well be San Saturnino, patron saint of Pamplona, preacher of the Gospel here and minister of the baptism of Firmo and his family.

Archbishop's Palace of Pamplona. Images of San Fermín and San Saturnino

Amparo Castiella, 2013

Since its inauguration in 1740, the interior of the palace has undergone several modifications required by successive needs of habitability and administration. Nevertheless, it retains some interesting original elements, such as the staircase, described by Pilar Andueza as "very interesting and even somewhat disconcerting, due to the optical games and the constant changes in perspective it offers". It starts from the courtyard in two parallel flights, like the so-called "imperial stairs", which converge on the first landing, from the center of which starts another flight parallel to the previous ones, which ends on the second floor; from here it continues ascending converted into a single staircase. The tracery is covered by groin vaults and lunettes; and the box is under a vaulted dome, with squares and a central rosette, in which episcopal motifs are not lacking as plastic references. It does not receive the illumination of an upper body of lights, a frequent case, but laterally, by means of two windows that open to the main façade.

Archbishop's Palace of Pamplona. Staircase

Pilar Andueza, 2004

To the bishop don Gaspar de Miranda y Argáiz (1742-1767) the construction of the chapel and the altarpiece that is conserved in her is owed. Made between 1747 and 1748 by José Pérez de Eulate, it was gilded by the painter Pedro Antonio de Rada: in him three niches shelter the bundles of San Fermín, San Ignacio de Loyola and San Francisco Javier; and it culminates it a painting framed in golden oval, that represents Our Lady of the Tabernacle, of Toledo.