August 17, 2014

Lectures

THE MONASTERY OF TULEBRAS

Architecture for the Cistercian charism. The work and the days in the monastery

D. Ricardo Fernández Gracia

Chairof Navarrese Heritage and Art

The origin of the Cistercians lies in the monk Robert who, with several followers, withdrew to Citeaux, a place section in Burgundy to put on internship the ideals of the Benedictine rule at the end of the 11th century. His fame attracted Stephen Harding who took it upon himself to summarize the statement of core values of those reforming monks, restless and anxious to participate in an authentically spiritual business . The real impulse came with the figure of Bernard of Clairvaux in 1112 together with three dozen Burgundian nobles and the approval of the Carta Caritatis in 1119 by Calixtus II, facts from which a process of rapid expansion began, with ideals of prohibition of all luxury in housing, clothing, food, at the same time that it recommended that the only tasks of the monk were the praise of God and the physical work .

In 1133 there were already 69 foundations. Twenty years later, at the death of St. Bernard (1153), the issue of monasteries totaled no less than 343. By the end of the Age average there were 742 male monasteries and more than 700 nuns' monasteries. The new communities maintained a close relationship of dependence with the motherhouse. In all of them the same norms and the vigilance of the General Chapters meant that there were practically no exceptions that would break the uniformity of the order. In his writings, St. Bernard developed the ideals of work, poverty, knowledge of Christ and love for the Virgin in his saying Mariae nuncquam satis.

Regarding the construction of the monasteries, if we go back to St. Bernard himself and his writings he gives us guidelines for the sobriety of the buildings when he affirms in the Apology to William: "They try to excite the devotion of the coarse people by the corporal attractions and not to excite it enough in the spiritual ones... As candelabra, one sees real bronze trees carved with admirable art... Oh vanity of vanities, but more madness than vanity!...". The General Chapter of 1134 recalled: "We prohibit that in our churches or in any of the dependencies of the monastery there are pictures or sculptures, because precisely to these things one directs one's attention, with which often the benefit of a good meditation is harmed and the Education of the religious seriousness is neglected".

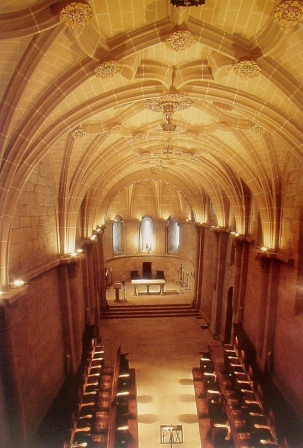

Church of the Cistercian monastery of Tulebras

(Photo: Carlos Becerril)

The architecture of the monasteries has been described in different ways by different specialists. Chueca Goitia considers it as a rationalist movement in plenary session of the Executive Council XII century, "with all the characteristics that will have the most modern analogous artistic revolutions... condemnation of all superfluous ornament, free expression of the Structures and frank nudity of the construction materials". Martín González writes of Cistercian architecture as a transitional art between Romanesque and Gothic. Azcárate considers Cistercian architecture as another chapter of Proto-Gothic architecture despite its own particularities, with great prominence in the diffusion of the ribbed arches and ribbed vaults. Finally, Yarza denies the existence of a Cistercian style in formal terms, "although not in the field of the organization of a monastery the answer must be affirmative". Víctor Nieto, following the latter, considers that the "criticism of the Cistercians against luxury and the ostentation of riches in the temples was not a praise of poverty, but of austerity and interior religious life...".

In what there is unanimity in following what Braunfels wrote: "The plan of the ideal Cistercian monastery represents a very mature organism, in which everything has been foreseen, where every superfluous detail has been avoided, capable of being built by elements of equal characteristics and where the temple only occupies a place of honor thanks to its greater dimensions. Severity and clarity dominate the structure of the plan". The monks who observed a strict enclosure within the monastic complexes throughout the hours of the day, had perfectly distributed time to pray the canonical hours in the monastic temple in which they prayed and chanted the divine official document with the seven canonical hours.

The cloister, a place for meditation and reading, and at the same time the organizer of the spaces and the axis of community life, was the true nerve center of the entire monastery and had direct access to the church and the rest of the monastic dependencies. Throughout its four pandas or bays, various doors of greater or lesser importance and dimensions gave access to the dependencies of the community life.

The capitular conference room , following the Rule of Saint Benedict, was destined to deal with important matters under the presidency of the abbot and his summons to the rest of the community. In this conference room all the monks met with the abbot, they read the rule, each monk could personally recognize breaches of the rule or could be accused of it by another monk ("That such a one ask forgiveness and fulfill the penance imposed on him for his fault.... there obey in all things the Abbot of the same and his chapter in the observance of the holy Rule or Order and in the correction of faults". Letter of Charity).

The rest of the dependencies such as cillas, refectory, dormitories, kitchen, latrines, scriptorium... etc., followed precise norms, in general, in dependence with the uses and functions described by Saint Benedict in his Rule, insisting on silence and meditation of the word of God, above the contemplation of images that in the history of the Church had a real slowdown after the hatching of the Romanesque period and the flowering of the Gothic period.