February 12, 2014

Global Seminars & Invited Speaker Series

CONVENTUAL PAMPLONA

The Hispanic convent city. The monasteries, palaces of faith.

D. Cristóbal Belda Navarro.

University of Murcia

For the Pamplona conventual cycle, two conferences inaugurated the sessions. The first dealt with the Spanish conventual city, starting from the model structured around the exhibition Moradas de grandeza to develop an essential argument in the configuration of the traditional Spanish city.

The fundamental motif that articulated the lecture was based on the fiction of a traveler who toured the main cities of the crown and, in his observations in his imaginary travel diary, he recorded the features observed and analyzed in those places he visited.

His surprise was determined by an element common to the Spanish city. Such was the predominance of a religious atmosphere visible in every corner and in every silhouette of the main urban buildings. This Levitical character, so solidly linked to the city, captivated his spirit and awakened his curiosity. From the astonishment produced by the way religion penetrated all sectors of human life, the imaginary traveler tried to know the causes that originated that imago urbis so characteristic.

In his chronicle, the traveler narrated the essential motifs of the baroque city, dominated by towers and bell towers and by hidden cities open to the city, but closed to all eyes. He soon understood the mechanisms that regulated such exceptional urban planning. Religious foundations constituted the symbolic boundary of an unknown world designed to accommodate a common life dedicated to prayer and silence.

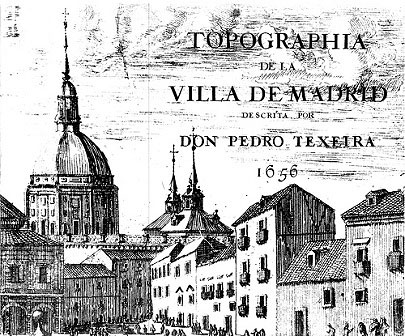

Topographia de la Villa de Madrid, Pedro Texeira, 1656.

Those spaces conceived according to the precepts of each monastic rule constituted a divine prison in which one lived and died with no other consolation than that offered by voluntary withdrawal from the world. The rules and constitutions determined not only different ways of life but also proposed constructive models in accordance with their ideals. The urban history of the West was essentially the history of a way of life that, after Trent, encouraged the conventualization of the city in a slow and secular process that conditioned the way of seeing the city.

Religious architecture thus became an essential element of urban planning, offering two different ways of life. On the inside, dominated by the basic features of convent life; on the outside, through the gradual control of urban life in its essential features: image of the city, presence in the street and social action. In this way, the traveler could construct the conventual geography and understand the rank attained by the cities that saw in their spaces, armies of angels that constituted the joy and consolation of the whole town.

The argument of the second intervention(The monasteries, palaces of faith) continued the fiction of the traveler. Having understood the essential features of the telltale signs of that conventual city, he wanted to satisfy his curiosity by penetrating into the interior of those hidden cities to learn about their peculiar existence. Once the symbolic frontier of the conventual walls was crossed, the curious learned to walk through its spaces by the hand of the conventual rule, true guide of life and conduct and mirror in which the virtue of its founders was reflected.

The rule and the monastic constitutions reflected the intentions of the founders. Both the one and the other needed a gradual adaptation to face new and unknown problems without breaking with the past and remaining faithful to the original principles. Through those texts, the traveler learned about the life and customs of those enclosures, appreciated the strength rules and regulations of their principles and understood how in their pages was written the history of the buildings, the organization and distribution of spaces, the regulation of the interior life, the elements favoring the foundation and even the choice of an architect who was well educated in art.

The traveler did not need, therefore, more guide than that offered by the monastic rule and by the constitutions written over time. He understood the meaning of the ceremonies, the nature and configuration of the shared spaces (cloisters, churches, chapter halls, refectory, libraries...), of those dedicated to retreat, prayer and silence (cells), communication with the outside (parlors, rule door), and the reasons why that mysterious and unknown world was surrounded by high walls and thick grilles without a porthole or hole through which anything could be registered either from outside the monastery or from inside it.

Locutorio of the Encarnación de Ávila monastery

High walls and thick bars were typical of monasteries and convents.

That voluntary isolation produced special forms of architecture that regulated daily movements, recreations and simple communication with the outside world, to the point of understanding how the inspiring principles of conventual architecture were not based on aesthetic norms but on intangible and immaterial values. Until the monastery became a visible scripture that taught the visitor the fundamentals of the rule and doctrine as the backbone of a way of life determined by poverty, chastity, solitude, isolation and the inviolability of the enclosure until reaching the condition of a self-sufficient community. issue In this way, the traveler understood the reasons why a monastery grew with certain dimensions, with an adequate number of inhabitants and with self-sufficiency needs satisfied by the orchards and gardens that surrounded them. In short, he also understood why in a monastery, the church and the Library Services constituted the basic units of its internal organization. Prayer, culture, artistic and literary creation also went hand in hand with conventual life.