October 29, 2014

Global Seminars & Invited Speaker Series

V CENTENARY OF SAINT TERESA: ART, HERITAGE AND SPIRITUALITY AROUND SAINT TERESA

St. Theresa and the Arts

D. Ricardo Fernández Gracia

Chairof Navarrese Heritage and Art

We can highlight three major aspects of St. Teresa's relationship with the arts. Firstly, her attitude towards images, her opinion of them, as well as the commissioning of others that she acquired or provided for her foundations. Secondly, all her iconography, exceptional in its abundance and with numerous types, which constitutes a chapter A among the representations of the saints in the seventeenth century. Finally, we must consider that the foundations of the Barefoot and Discalced Carmelites treasure unique sets of architecture, sculpture, painting and sumptuary arts, together with a singular intangible heritage, which has survived for centuries in the female enclosures.

"It is a great gift to see an image of the one we love for so many reasons." Her relationship with the images and the Teresian iconostasis

The attitude of the Saint towards the images, in the century of Humanism in which they were attacked and discussed, is not only placed in full Spanish tradition, but even introduces them in passages of her life and in the world of her mystical experiences. As an example, when narrating the death of her mother, she says: "as I began to understand what I had lost, I went to an image of Our Lady and begged her to be my mother..." (Life, 1,7).

In the saint's time, the images were extraordinarily effective due to their scarcity, when the time for their contemplation was abundant, so that those who looked at them could extract different sensations and evaluations. In final and as David Freedberg has masterfully written, comparing the past with the present, we no longer have "enough leisure to contemplate the images that are before our eyes, but in the past people did look at them; and they made contemplation something useful, therapeutic, that elevated their spirit, gave them comfort and inspired fear. All in order to reach a state of empathy".

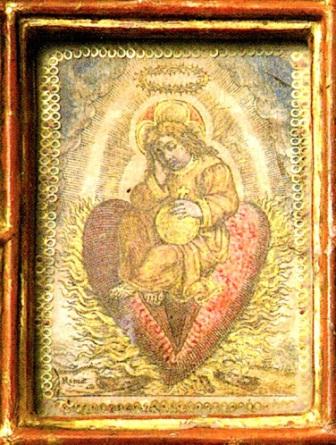

To the issue of images that Santa Teresa could contemplate in the temples and by his travels must be added the prints he owned: one with Baby Jesus sleeping on the heart, alluding to the biblical phrase Ego dormio et cor meum vigilat. Also the illustrations of the Breviary, published in Venice in 1568 and preserved in the Carmelites of Medina del Campo.

Stamp belonged to Saint Teresa of Jesus, preserved in the Carmelites of Tarazona.

In the Way of Perfection, when considering Christ in the Eucharist, he considers it foolish to look at his picture, but admits his image, in some circumstances, with the following consideration: "Do you know when it is very good and something in which I take great delight? For when the person himself is absent, or wants to give us to understand that he is absent with many drynesses, it is a great gift to see an image of the one we love for so much reason".

Father Gracián affirms in his Escolias a la biografía del Padre Ribera: "The holy Mother Teresa of Jesus was very devoted to the well painted images and according to the Nicene Council II, they are great part to guide the souls to God. And although it is true that many times the image of Jesus Christ was represented to her in her imagination as resurrected, with a crown of thorns and wounds and a white mantle, I know that she had more faith with any painted image. Because to adore the image, she had the faith that it was to adore God".

We know of some images that she acquired, personally, for her foundations, for example for the Carmel of Toledo, in a passage that she herself narrates: "I left very happy, because it seemed to me that I already had everything, without having anything; because I must have had three or four ducats, with which I bought two canvases (because I had no image to put on the altar) and two pallets and a blanket"(Foundations 15,6). And we also know his concern to send to some of his little dovecotes devout images, like the sculpture of the Virgin for Caravaca, according to the testimony of a letter in which he writes: "Now I have to send to Caravaca an image of Our Lady that I have for them, very good and big, not dressed, and a Saint Joseph they are making me, and it will not cost them anything".

The iconography

Most of the iconographic testimonies, as well as the literary ones, end up placing us before a baroque saint, after her death, in tune with the unbridled, sensual and theatrical, very much in tune with the culture of the Baroque. In this regard, Teófanes Egido recalls how the life of the saints did not end with their death, since, after leaving the earthly world, another decisive stage began in their historiography: that of the fabrication and reception of their transfigured figure.

In the diffusion of her image played a great role the engraved portraits that illustrated her works, almost always from the portrait that Fray Juan de la Miseria made of her in 1576, but above all the images that after her beatification popularized her facet as a writer. For the cycles that narrated selected scenes of her life, the models provided by her illustrated lives stood out, particularly the "wunder vitae", by Luca Ciamberlano and even more the collection of prints made in Antwerp by Adriaen Collaert and Cornelius Galle, on the initiative of Mother Anne of Jesus and with the participation in the selection of passages of Anne of St. Bartholomew herself, in 1613.

The first portraits of the saint, such as this one commissioned by Don Francisco de Soto,

were based on the portrait executed by Friar Juan de la Miseria in 1576.

The graphic models and the accounts of his own life are essential to know his rich iconography, always with the representation of sensitive forms with which the imagination translated ineffable greatness. Among all of them, the most widespread was the famous vision of the transverberation, sublimated by Bernini himself in the Cornaro Chapel. The devotion to that vision, narrated in chapter XXIX of the book of his life, grew so much that in 1726 the Order of Carmel got the Holy See to grant its celebration with its own Mass on August 24.

Along with the mystical nuptials, the vision of Christ at the column, the imposition of the necklace, etc..., the painters, following the wishes of her promoters, also painted the saint in relation to themes very much in line with the Catholic Reformation, such as the Eucharist, penance or intercession for the souls in purgatory. It all fit very well in the seventeenth century, so given to marvelism, ecstasies and celestial experiences.

Painted, sculpted and engraved representations of the saint, studied in monographs such as those of Laura Gutiérrez Rueda or Jean de la Croix, served as a complement to the words of the sermons and her popular joys to know and explain the life and works of the saint of Avila. In times when people did not know how to read or write, images became irreplaceable elements for such purposes of spreading culture and catechization, together with preaching and other oral and musical means.

Images and propaganda, together with the attraction of the woman wanderer, seeker of God and writer, led to the saint being declared patron saint by the Cortes of Castile and numerous cities, competing with the cult of St. James in the first half of the 17th century, although it was the Cortes of Cadiz that signed her board of trustees over the nation.

Tangible and intangible heritage in the convents of Descalzos and Descalzas: tracist friars and artist nuns.

Along with outstanding sets of conventual architecture, always with a very similar model , the interiors of the churches of the order preserve rich altarpieces and chapels, witnesses of secular devotions to their saints and to Saint Joseph, the Virgin of Carmen and the souls of purgatory.

As for the convents, it is necessary to emphasize the role played in their construction by the plans and traces drawn by the tracists of the order, which explains, in part, the similarity of numerous sets of facades, churches and altarpieces. In this regard, we must remember that in the Constitutions of the Discalced of 1604, in full expansion, we read: "those who are received for the lay state, must be artisans, and not of any art but of those that can serve in the Order, such as assembler, carver, sculptor, carpenter, mason, gilder, painter, surgeon and that they are skilled in these arts and are not beginners". The same text ordered: "from now on, no convent is to be built, no work B is to be made, without the preceding drawing of the order's artisans, in which the form it is to have is outlined...".

They were not left behind, some friars painters like friar Juan del Santísimo Sacramento and, above all, many nuns in the tasks of the sumptuary arts, emphasizing skillful embroiderers. Rare is the convent that did not have some of them and that preserves rich palliums or ternos made with the refinement and delicacy of acu pictae.

Along with this material heritage, the religious communities have jealously safeguarded, until recently, a rich intangible heritage, secular traditions, which constitute unparalleled testimonies of the collective conscience and keys to the understanding of a certain religiosity. Among all this heritage, cooking recipes, sentences to recite when going to bed or getting up to the sound of the ratchet, dances, poetry, theater, even events as unique as the placement of the crib with its rituals, are still recoverable. Today, it is of great interest to collect all this because of the threat of disappearance and the need to preserve living cultures, threatened by globalization.

The image that presides over the altarpiece of Saint Teresa in the convent of the Discalced Carmelites of Pamplona follows the models popularized by Gregorio Fernández.