2 November

lecture

THE ART OF NAVARRA IN THE GREAT MUSEUMS (I)

Medieval art from Navarre in the National Archaeological Museum

Ángela Franco Mata

National Archaeological Museum

There is very little medieval art from Navarre in the National Archaeological Museum. It is worth asking why, considering the disproportion with respect to other regions of Spain. A partial answer is undoubtedly to be found in the fact that it was not included in the Scientific Commissions which toured the country between 1868 and 1875 on the occasion of the creation of the museum. Subsequently, the objects entered were independent and isolated acquisitions. They are the altarpiece of San Nicasio and San Sebastián, from Estella, and a small treasure found in the Calle de la Merced in Pamplona. I have left out the two mosaics from Soto del Ramalete, Tudela, and Arellano, from the 4th century, as they are Roman works.

International Gothic painting in Navarre began with two altarpieces commissioned by Martín Pérez de Eulate [better known as Martín Périz de Estella] in 1402 and 1416 respectively for the family funeral chapel in the church of San Miguel in Estella. The first of these, dedicated to Saint Nicasius and Saint Sebastian, is on display in the National Archaeological Museum, where it was taken between the end of the 19th century and before 1925, as it appears at that date on the guide of Álvarez Osorio. The second, dedicated to Saint Helena, is currently located in the northern apse, next to the tomb of its promoter. Devotion to the Holy Cross was extraordinarily popular in the leave Age average; an example of this is the beautiful altarpiece dedicated to it, the work of Miguel Jiménez and Martín Bernat, which comes from the parish church of Blesa (Teruel) and is on display in the Museum of Saragossa. Martín Périz de Eulate was a prominent figure at the court of Charles III the Noble, for whom he was mazonero, position , a position he held even in the early years of the reign of Doña Blanca. He was a contractor for the palace of Olite, which brought him wealth and a higher social status, and was the head of a lineage that would become one of the most influential nobility in Estella and the kingdom. In the tomb he wears the attire of a knight, with armour and sword, and is marked with his heraldic coat of arms.

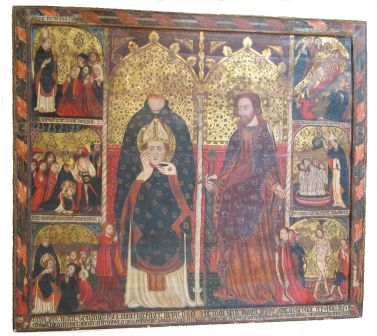

Altarpiece of San Nicasio and San Sebastián. From Estella. National Archaeological Museum

The altarpiece of San Nicasio and San Sebastián, which in my study on "La lectura de texto e imagen en la pintura bajomedieval hispánica" [XXVII Ruta Cicloturística del Románico Internacional, Poio, 1 February-21 June 2009, pp. 89-102] I have included in the section documentary/hagiographic language, has a quadrangular structure and seems to be a transposition of the mural painting, with which it coincides in the arrangement of the panels and texts. It is divided into four streets, the central ones with the patron saints framed by pointed arches and at the feet of each of the donors, Martín Pérez de Eulate and Toda Sánchez de Yarza, of reduced size, according to the law of hierarchical perspective. The side streets are dedicated to the narration of the life of each one of them. The content of each scene is explained by means of the corresponding texts.

Saint Nicasius, often associated with Saint Sebastian, is represented decapitated with his head mitred between his hands and dressed as a bishop. In the left street his life and martyrdom are narrated in three scenes: preaching: HOW (...) HOW:HE PREACHED (...), beheading THEY BEHEADED: SAINT:NICASIUS and miracle of healing of the blind HOW:HE ENLIGHTENED:THE:BLIND:SAINT:NICASIUS.

St. Sebastian, officer of the palatine guard of Diocletian, was assaulted, accused of being a Christian, although he dies scourged. He is dressed as a palatine nobleman, with beard, according to typical Gothic iconography, with sword in one hand and arrows in the other; the crown of flowers has been stamped as an ornament of his attire. His life and martyrdom are narrated in three eurhythmic scenes of those of St. Nicasius: several disciples burned: AS: THEY:ASAN:A LO(S) Q(UE)..., their baptism by the saint AS:THEY:BAPTIZE:A LOS Q(UE) DI(...):IN S(ANT) SABAST(TIAN) and finally the saint is asaeticized: HERE:AS:SAETEAN:A SANT:SABASTIAN.

The registration at the bottom gives the date of execution of the work and the principals. It reads: ANNO:D(O)M(INI):M:CCCC:SEGUNDO:ESTA:OBRA:FIZO:FACER:M(ARTIN) P(ER)IZ DE (EULA)TE MAESTRO:MAYOR:DE:OBRAS:DEL SENNOR REY (ET)TODA (SANCHEZDEYARZ)A SU MUGER: A ONOR:ET SERVYCIO:DE DIOS:ET DE SENYOR:SAN SABASTIAN ET DE SENT:NICASIO:ET Q(UE) POR LA ... RE:THESE ....: N(OST)RIS:SEAN:BONOS MEDIADEROS:A DIOS:POR MI:ET:POR TODO.

In the chapel there is also the altarpiece dedicated to Saint Helena, whose documentation of both has been extracted by Father Goñi Gaztambide. Some historical circumstances are illustrative, which are collected in a document issued in Rome and dated June 1, 1500, exhibited by the vicar general of Cardinal Palavicini, in the presence of the gentleman Lope Vélez de Eulate, where several points related to the saints Nicasio, Sebastián and Santa Cruz are consigned. Several cardinals granted one hundred days of indulgence each to the faithful who visited the chapel of San Sebastián, located in the parish church of San Miguel de Estella, and gave alms for its conservation and repair on five specific festivities. In addition, for the eradication of an epidemic that was plaguing the city, he requested the intercession of the holy martyrs Nicasio and Sebastián, and ordered that on Sundays and solemn feasts, alms could be asked for inside and outside the church of San Miguel and the other churches of Estella for the luminaria of San Sebastián. The alms would be deposited in a trap inside the mentioned chapels and would be invested in luminaria, masses, conservation and adornment of the chapel, and perpetual prayer in favor of the donors.

The altarpiece of Santa Elena partially preserves the indication of the donors in a registration located between the body of the altarpiece and the bench, whose transcription reads: "This altarpiece was made by Martín Periz de Eulate... of Mr. Rey and Toda Sánchez, his wife, neighbors Destella in honor and reverence of our Lord God and the Holy Cross [...] in the lanno of the birth of Our Lord Ihesu Xto of one thousand CCCC and seze", coinciding with the document published by P. Goñi.

The variety of funerary monuments existing in the National Archaeological Museum has allowed us a wide imaginative deployment for its exhibition. I have considered it appropriate to evoke a funerary space showing monuments of various types and styles to give the idea of original sites.

Treasure from Pamplona, found in Calle de la Merced

National Archaeological Museum

The Pamplona Treasure was found inside a Mudejar scarcella and a 14th century bag in 1940, and was included by Mateu and Llopis in a general article on "Hallazgos", in the magazine Ampurias in 1945. Subsequently, except for the references in Adquisiciones del MAN ( Madrid, 1947) and the contribution of my good colleague the late Mercedes Rueda in her book on florins, little more has been written. The exhaustive cataloguing carried out by Mar Gómez Talavera in 1999 is currently awaiting publication. It is composed of 117 gold pieces, from different origins and mints, Aragon, Tortosa, Perpignan, Valencia, Zaragoza, Seville, Venice, France and England. Its weight is 374.55 g. Along with this bulky lot of coins was a beautiful ring of the same material with a bluish stone. It is undoubtedly a treasure hidden by its owner, presumably a pilgrim from Santiago.

Finally I dealt with some Marian images offered for sale to the State, one Romanesque (1926) and two Gothic (2009, 2014), one of marble, from the 14th century and another of wood, from around 1280, which corresponds to the subject of the copies of Los Arcos, Miranda de Arga, Arizaleta, Fitero, Berbinzana, Mendigorría, Artaza and Ubago, from the cataloging of C. Fernández-Ladreda, which were not acquired.

It belongs to the first group of the medieval Marian imagery, which it calls in the strict sense, catalogued by Clara Fernández-Ladreda. It is a very well defined group , whose formal characteristics are defined as follows: the feet of the Child rest the right one on the corresponding leg of the Mother and the left one rests on her lap, details of the dress, with a very pointed stiffener and predominance of the angular folding, especially visible on the edge of the veil and lower part of the mantle, and by the subject of attributes used, in the case of Mary, of floral character, in the case of Jesus, book Closed. Based on Randall's chronological proposal for an existing copy in The Cloisters, New York, similar to the Virgin of Miranda de Arga, in the last two decades of the 13th century, the aforementioned author establishes the same chronology, since both are attributable to the same artist. For my part, I attribute to the new copy the authorship and consequently the same chronology, which for the entire group corresponds to the last third of that century [Clara Fernández Ladreda, Imaginería medieval mariana en Navarra, Pamplona, Gobierno de Navarra, 1988, pp. 150-168]. The fact that the elegant crown, which adorns some of the images of the group, has disappeared in a certain sense distorts its originality, although the characteristics of the work remain unaltered. It even conserves the polychromy, which brings it closer to the Virgin of Miranda de Arga.