4 October

lecture series

SANCTUARIES IN ESTELLA LAND

Architecture of coplillas and gozos. Marian shrines in Tierra Estella

Mr. José Javier Azanza López

University of Navarra

Marian sanctuaries in Tierra Estella: the origin of devotion

From the 12th century onwards, Navarre witnessed the consolidation of Marian devotion with the rise of sanctuaries and hermitages presided over by an image of the Virgin under different invocations to which pilgrims go on pilgrimage with prayers and joys. This can be seen in Tierra Estella, where the origin of Marian devotion is often legendary, so that legend adorns the cult: the image was hidden in times of the Muslim invasion to prevent its desecration and then miraculously found. Beyond the historical reality, the legends confirm three aspects: that the beginning of the cult of the Virgin dates back many centuries; that some extraordinary event must have been the reason for having erected sanctuaries in her honour; and that over the centuries, the favours granted by the Virgin to the localities that have taken refuge under her protection have been singular.

Legend and history merge in the apparition of the Virgin of El Puy in Estella in May 1085 to some shepherds from Abárzuza looking after their livestock, who, guided by mysterious star-like lights, found the image of the Virgin inside a grotto; this is recorded in the coplilla: "This is the Star / that came down from heaven to Estella / as a gift from her"; and also in the legend of a 17th century canvas kept in the convent of the Conceptionist Recollects in the town: "I am the Star / descended from heaven to the ground / to give light to Estella / to be its Patron Saint".

It also does so in the findingof the images of the Remedies and of the Miracle of Luquin by a farmer ploughing the field with his yoke of oxen (Fig. 1), when the grille came up against a large stone which, when removed, revealed a hollow in the shape of a grotto concealing the two captive Virgins, as the local couplet records: "Astounded were his eyes / when he saw the Virgin's face / on the two pious effigies / that augured happiness and peace". Also, in the singular event of the stubborn mule that carried an image of the Virgin on its back to Los Arcos, but when it reached the place where the Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Loveof Santa María de Gracia de Cárcar stands today, it refused to go any further, a legend that is repeated in other examples from Tierra Estella, such as the Virgen de las Angustias de Lodosa. For its part, devotion to the Virgin of Mendigaña de Azcona has its origin in the miraculous apparition of Mary to a pious neighbour who was ill, announcing to her, at the same time as healing her, that her image was hidden in the cima of the mountain, where it should be venerated.

Popular worship: gozos and coplillas, novenas and pilgrimages

After the finding, devotion and worship to Mary are adorned with hymns, gozos and coplillas, popular poetry that is sung in the pilgrimages, novenas and feasts of each Virgin, mainly in the months of May and September, in which her children pray and ask for the favour of the Mother who appears as: leafy tree, fertile palm, beautiful rose, tasty nectar, beautiful pearl, eagle that teaches her chicks to fly, moon without waning, shining light in the night, cloud in fiery day, divine magnet, bright and beautiful beacon of seas and mists, aqueduct and channel of all graces, our refuge, ladder to heaven... All are compliments to Mary.

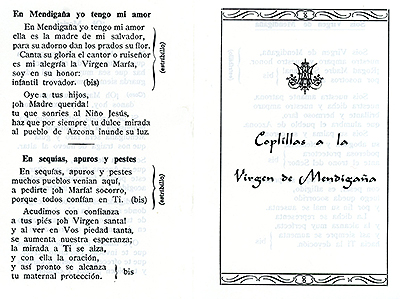

In many cases the faithful do not forget the remedies received from the Virgin in the face of public calamities, as is recorded in the couplets to the Virgin of Mendigaña: "In droughts, hardships and plagues / many peoples came here, / to ask you, O Mary, / for help, / because they all trust in you" (Fig. 2). In similar terms, the religious who preached the Sermon on the Birth of Our Lady addressed his audience from the pulpit in 1783: "Let us come here, then, in all our needs, for here we shall find help in all our calamities... This Lady is the one who brings us fertility in the fields, abundance in the harvests... She delivers us from plague, from stone, from lightning and from other misfortunes that we deserve for our faults. From this blessed mountain she watches over the people and their inhabitants as a sovereign watchtower and invites us to turn to her in all our adversities". For all these reasons, they say their joys: "You are, Virgin of Mendigaña, / our protection and our honour, / Pray, Sovereign Virgin / for us to the Lord, / You are our loving patron saint, / our happiness and our protection / a shining beacon, / that illuminates the village of Azcona". And the hymn "Oh María" sings to her: "Sovereign of heaven, Lady, / who in Azcona has an altar, / this fervent people implores you / welcomed by your maternal love".

In Luquin, the popular song recalls: "Two saints we have / they are both one / because there is only one / the Mother of God". In September, the solemn novena to Remedios and Milagro is celebrated, which are praised in their joys: "En Remedios poderosa, / de Milagros obradora; / Dispensadnos, gran Señora, / vuestra influencia amorosa. / In Luquin is the source/ of health and life; / all over the world spread / it follows its pleasant current, / diligently remedying / the thirst that harasses the weak... / Your fame, sweet proclamation, / publishes your wonders / in Álava and the Castillas, / in Navarre and Aragon; all are relieved / by your pious protection. / In your chapel, / the sampleof your wonders is displayed; / there are hundreds / of gifts that man presents; / and contemplating them increases / the astonishing admiration".

The people of Cartagena also go on pilgrimage to the Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Loveof their patron saint, the Virgen de Gracia, competing with beautifully decorated floats and singing hymns to her: "Sweet, Mother who inspires our accent / sweet, sweet Mother of love / look at your people who sing / and the faith of a lover tells you love... / Today this town acclaims you its Queen, / O Virgin of Grace! Let the cheers ring out, let us say Glory, / Glory to Mary our coat of arms".

Marian Images: Mary, Mother and Intercessor

The protagonists to whom the faithful flock with their songs and hymns, gozos and coplillas, are Marian images carved in polychrome wood that show Mary as Virgin and Mother, most of them from the Gothic centuries. Thus, the Virgen de los Remedios de Luquin (Fig. 3) is an image from the second third of the 13th century, although Romanesque traces still survive in it; also Gothic from the 13th century is the Virgen de Mendía de Arróniz, although in 1951 it was plated in silver except for the face and hands; and the Virgen de Gracia de Cárcar dates from the first half of the 14th century, while the Virgen de los Remedios de Sesma and the Virgen de Mendigaña de Azcona date from the second half. The beautiful carving of the Virgen del Milagro de Luquin (Fig. 3), a Renaissance work with Flemish reminiscences from the first half of the 16th century, enriched with a colourful 18th century Rococo polychromy in which Marian scenes such as the Annunciation and the Visitation inscribed in rocaille medallions stand out. The Virgin of Montserrat in Lodosa is also Baroque from the 17th century.

A new shrine for image and worship

Although Marian devotion in Tierra Estella dates back to the Middle Ages average, the arrival of the Modern Age did not mean a decline in devotion; on the contrary, the Renaissance and Baroque centuries were a period of flourishing and revitalisation of Marian devotion, which is reflected in the countless brotherhoods dedicated to the Virgin, as well as in the pilgrimages, processions and novenas held in her honour. As a result of this devotion, a large number of Marian shrines and hermitages are now being built or remodelled Structures; they are buildings of great devotional value whose silhouette is sometimes silhouetted against beautiful scenery, enriched with plasterwork, altarpieces and paintings that make them very sumptuous.

The new sanctuary for the image finds its raison d'être in the reduced dimensions or poor state of conservation of the primitive one, which lacks the necessary conditions for worship, as we read in the applicationof licenceto build a new temple that in 1704 the patrons of the basilica of Los Remedios y Milagro de Luquin, conserved in the Diocesan fileof Pamplona, submitted to the Bishopric: "The basilica is too small for the crowds that are usually very numerous, especially on the feasts of Our Lady, both of the residents of the said place and of outsiders from all over the kingdom and elsewhere, due to the miraculous nature of the Holy Images that are placed in the said basilica consecrated to their worship and veneration, and due to the great devotion to them of the faithful, both healthy and sick, in search of health and spiritual and temporal remedy for both, with the great faith and devotion they have for the said holy images".

Where are these new shrines built? In general, they occupy the same site as the previous Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Lovewhich they replace, although occasionally they look for a larger site in order to be able to erect a more capable building (Remedios and Milagro de Luquin). They are located in the town centre of the town, or very close to it (Montserrat de Lodosa); often in the highest part of the town, as a watchtower or spiritual beacon (Mendía de Arróniz, Mendigaña de Azcona, Remedios de Sesma); and they can also be located at some distance from the town centre, a location that facilitates pilgrimages and pilgrimages to the sanctuary (Gracia de Cárcar).

The financing of the new sanctuary is a collective businessto which all the neighbours contribute to a greater or lesser extent as an expression of filial love, with their alms and testamentary bequests, whether in cash or in kind, offering wheat in summer and other products such as grapes in autumn. Sometimes the bequests came from other parts of the peninsula and the Indies, gifts from those sons who, far from their place of origin, had made their fortune in the world of administration, the military or business; a large part of the wealth from Madrid and America sent to the towns of Tierra Estella was destined for their basilicas and sanctuaries, test, a tangible sign that the people of Estella keep alive the memory of their patron saint. Thus, Bernardo de Nagusia sent a donation from Madrid to Mendía de Arróniz, as did Martín García de Embila from Cádiz for Remedios and Milagro de Luquin. Among the bequests from the Indies were those of Lorenzo Hermoso de Mendoza, Perpetual Alderman and Justice Major of Caracas, for Mendía de Arróniz, and of Captain José de Royo (Lima) and Juan Jerónimo Solano (Mexico) for Remedios de Sesma; the former also sent a carved silver bequestmade up of two crowns and an altar frontal.

As for the craftsmen who took part in the construction of the building and its subsequent ornamentation, the long list includes some of the main masters active in Navarre in the 17th and 18th centuries, also from Guipuzcoa, La Rioja, Aragon and even France, with a special mention for Juan Antonio San Juan, overseer of works for the Bishopric of Pamplona, who carried out both the designof traces and the work of recognition and appraisal of the works.

Focusing our interest on the architecture of the new sanctuaries, most of them have a Latin cross plan with a single nave, a marked Wayside Crossand a straight chancel, closely following the models of convent architecture; the chapels of Cárcar, Luquin, Lodosa and Sesma are similar to this outline. For its part, Mendía de Arróniz samplehas a box-shaped floor plan, configured as an elongated rectangle whose five-bay nave is extended at the chancel, with the Wayside Cross absent. And Mendigaña de Azcona is in the form of a Greek cross with a slightly elongated longitudinal axis, a two-bay nave, Wayside Crosswith a large developmentand a straight chancel, giving the interior the sensation of a centralised space. It is unusual for shrines in Estella to have a "camarín", a private space for the image behind the area of the chancel with which it was connected through the high altar, although it is present in Nuestra Señora de Codés and San Gregorio Ostiense in Sorlada, as well as in the now disappeared basilica of El Puy in Estella.

In the elevations, the nave bays are articulated by an order of pilasters topped with capitals (the elegant ones of Remedios and Milagro de Luquin with the presence of cherub heads) on which a moulded cornice rests. Half-barrel vaults with lunettes are used to cover the nave sections, the arms of the Wayside Crossand the chancel, while over the central Wayside Crossan orange averageover pendentives decorated with Marian themes, which in the case of Mendía de Arróniz give way to the Evangelists, with Saint Luke as the painter of the Virgin. Worthy of note at accredited specializationdue to its innovative nature is the cupola with wings that rises above the central section of Wayside Crossde Mendigaña de Azcona, as well as the profuse pictorial ornamentation and vegetal plasterwork that covers the walls and roofs of the sanctuary to make it one of the best examples of Navarre's decorative Baroque (Fig. 4). The superb wrought iron grilles that in many cases delimit the spaces of the nave and chancel should not be forgotten in the chapter on elevations.

The exterior is dominated by simple, rounded geometric volumes, like safes that protect the precious treasure inside. The façades, which concentrate the monumental and decorative interest, escape this sobriety. There is no shortage of architectural elements, such as moulded mouldings, carved pilasters and columns, as well as a plant foliage plaque that is as decorative as it is symbolic, the niche that houses a stone image of the patron saint and the attic at the top, which often becomes a belfry. This is the case of Montserrat de Lodosa, Remedios de Luquin and Mendía de Arróniz, the latter being the most monumental thanks to its four giant columns on a powerful base (Fig. 5), built in the first decades of the 18th century by the stonemasons Francisco de Ibarra and Francisco de Sarasúa according to the designs of Vicente de Frías, who years earlier had also designed the exceptional portal-cascade of the basilica of San Gregorio Ostiense in Sorlada. For its part, Mendigaña de Azcona retains traces of convent architecture in its austere rectangular configuration, while Remedios de Sesma has a brick mixtilinear façade with a stone doorway with epigraphy alluding to the construction of the building.

The ornamentation of the sanctuary: a programme of Marian exaltation

Inside, the ornamentation of the sanctuary unfolds a programme of Marian exaltation through altarpieces, sculptures and paintings that become a litany of love for the Virgin. The starting point is the main altarpiece, in many cases pieces of great quality commissioned from the leading retablists of the period, with Solomonic columns, stipes and a profusion of decoration. The image of the Virgin occupies the central space, while sculptures, reliefs and paintings depicting scenes from Mary's life are distributed along the rest of the aisles to form an iconographic programme to which Saint Joachim and Saint Anne, the Virgin's parents, are often added, flanking the central niche. accredited specializationWorthy of note for their quality are the major altarpieces of Mendigaña de Azcona (second decade of the 18th century, close to the style of Juan Ángel Nagusia) and of Remedios y Milagros de Luquin (Lucas de Mena, first quarter of the 18th century).

In addition to the main altarpiece, other altarpieces and paintings are located in the arms of the Wayside Crossand in the nave, sometimes dedicated to the patron saints of the town, but also with Marian significance. The pair of canvases sent to Mendía de Arróniz in 1686 by Domingo de Nagusia, a native of the town who lived in Madrid, where he was the business agent for lawsuits in the Court, and also the depositary and administrator of the free assets of the 9th Admiral of Castile Juan Alfonso Enríquez de Cabrera from 1665 to 1683, the year of the Admiral's death, are particularly noteworthy in this respect. One of them, sample, depicts the Virgin among angels, while the second shows Christ among angels dressed as a Jesuit, an iconographic subjectwhich follows the vision of the venerable Marina de Escobar and which acquired particular relevance in the first half of the 17th century in the Valladolid scene thanks to the painter Diego Valentín Díaz, who was followed by Diego Díez Ferreras and Felipe and Manuel Gil de Mena. Meanwhile, in Remedios and Milagro de Luquin hang two canvases of the Assumption and the Visitation, the work of the painter from Alava or La Rioja, Ramón Garrido, active in the first half of the 19th century in places such as Elciego (Alava) and Muniain de la Solana (Navarre).

In Mendigaña de Azcona, the mural painting is added to the furniture, with an iconographic programme which, as well as including references to the litany of the Lauretan litany, invokes the protection of Mary in two scenes that show her as Saviour in the dangers of life's journey to reach a safe harbour ("Sta. Maria succurre miseris... et a periculis cunctis libera nos"; "Ave Maris. Amica Stella naufragis") and as a firm defender of the castle of faith ("Virgo potens sicut Turris David. Mille clypei pendent ex ea..."). The programme is completed by her appearance to the sick neighbour indicating the place where her image was to be found ("Elegi et sanctificavi locum istum..."). And it continues in the sacristy with a new set of scenes of Marian symbolism, to which are added others of Eucharistic significance.

Ex-votos: grateful to Mary for the favour received

A special chapter is devoted to votive offerings, which tend to abound in sanctuaries, recalling the miracles performed by the titular image. Although there is a great typological variety (wax figures that reproduce parts of the human body, clothes, letters, weapons, medals, etc.), we focus our interest here on the votive offerings in which the donor opts for the image of the patron saint.), we focus our interest here on the votive offerings in which the donor opts for painting as a vehicle of expression to refer to the miracle, giving rise to medium-sized, vertical paintings in which the devotional value is greater than the artistic one; not in vain, their main goalwas to express gratitude, but also to leave reportof the event, contributing to the fame of the intercessor Virgin and generating an emotional reaction in those who contemplated it.

Two small votive offerings are preserved in Mendía de Arróniz, dated 1749 and 1772 respectively (Fig. 6). The first of these depicts the testimony of the local doctor Agustín de Zeaorrote, who, suffering from the painful disease of volvulus or colic miserere, was miraculously cured through the intercession of the Virgin of Mendía; consider the added psychological value of this votive offering in which no less than a doctor validates the "miraculous medicine" of the Virgin. The second corresponds to the Carmelite monk Miguel de Arviza, also evicted due to illness and healed by the portrait of Our Lady of Mendía offered to him by his parents.

Similarly, in Remedios y Milagros de Luquin there are two votive offerings dating from 1797 and 1840 which feature Benito Oliban, who fell out of a window into the street and was left for dead until his parents offered them to Our Lady of Remedies and he was healed, and the Urbiola resident Fidel Osés, who was cured of a serious illness after entrusting himself to the Virgin. In addition to these, there is a third which is of special significance because it is a "collective miracle", in the sense that it tells of the salvation of a shipwreck, as the accompanying cartouche states: "Shipwreck avoided through the intercession of the Virgin of the Remedies and the Miracle, when Captain Pedro de Colmenares was Captain of the Ship. Year 1794". Although we have not found a direct reference to the event, we do know from the publications of the time that in 1794 Pedro Colmenares had been promoted from frigate captain to ship's captain, later based in Cartagena; and that from September 1794 to September 1796 he was captain of the San Fermín, a 74-gun ship launched in the port of Pasajes in 1782, and which could perhaps be identified with the vessel depicted in the painting.

Conclusion

"From the desert of life / Mary is a leafy tree / that offers the sorrowful traveller / a sweet welcome; / to all the world she invites / with her delightful shade. / If you look at our desire / to enjoy you one day, / and you are, sweet Mary, / the ladder that guideto Heaven, / you can soften the ground / of such a thorny path".

This is how the children of Luquin implore the favour of their Mother Mary, taking refuge in the shade of her shelter and protection in the sanctuary that bears witness to the devotion of an entire village. And, like them, so many other inhabitants of countless towns in Tierra Estella who have been able to transmit, from generation to generation until the present day, a popular faith made up of legends and miracles, of coplillas and gozos, of novenas and pilgrimages, of medieval carvings and Baroque sanctuaries. An entire devotional and patrimonial bequestof great value that must be preserved in order to keep alive the signs of identity that have characterised the inhabitants of Tierra Estella for centuries.

Fig. 1. Luquin. Basilica of Nuestra Señora de los Remedios y del Milagro. Apparition of the sacred images. Photo: J. J. Azanza.

Fig. 2. Coplillas a la Virgen de Mendigaña by Azcona.

Fig. 3. Luquin. Images of Nuestra Señora de los Remedios (second third of the 13th century) and of the Miracle (first half of the 16th century). Photo: J. J. Azanza.

Fig. 4. Azcona. Basilica of Nuestra Señora de Mendigaña. Interior and main altarpiece. Photo: J. J. Azanza.

Fig. 5. Arróniz. Basilica of Nuestra Señora de Mendía. Façade. Photo: J. J. Azanza.

Fig. 6. Arróniz. Basilica of Our Lady of Mendía. Ex-votos. Photo: J. J. Azanza.

To find out more

Arraiza, Jesús, Saint Mary in Navarre. Devotion. Leyenda. Historia, Pamplona, Caja de Ahorros Municipal de Pamplona, 1990.

Azanza López, José Javier, Arquitectura religiosa del Barroco en Navarra, Pamplona, Government of Navarra, 1998.

Clavería Arangua, Jacinto, Iconografía y santuarios de la Virgen en Navarra, Madrid, Gráfica management assistant, 1942.

Fernández Gracia, Ricardo, El retablo barroco en Navarra, Pamplona, Government of Navarra, 2003.

Fernández Gracia, Ricardo, Andueza Unanua, Pilar, Azanza López, José Javier and García Gainza, María Concepción, El arte del Barroco en Navarra, Pamplona, Government of Navarra, 2014.

Fernández-Ladreda, Clara, Imaginería medieval mariana en Navarra, Pamplona, Government of Navarra, 1989.

Fernández-Ladreda, Clara, guide para visitar los santuarios marianos en Navarra, Madrid, meeting, 1989.

García Gainza, María Concepción, Heredia Moreno, Carmen, Rivas Carmona, Jesús and Orbe Sivatte, Mercedes, Catalog Monumental de Navarra, II*. Merindad de Estella, Pamplona, Institución Príncipe de Viana, 1982.

García Gainza, María Concepción, Heredia Moreno, Carmen, Rivas Carmona, Jesús and Orbe Sivatte, Mercedes, Catalog Monumental de Navarra, II**. Merindad de Estella, Pamplona, Institución Príncipe de Viana, 1983.

Laviñeta Samanes, Silvio and Ciordia Muguerza, Javier, La Virgen de Luquin, Pamplona, Gráficas Iruña, 1970.

Salve. 700 años de arte y devoción mariana en Navarra (cat. exhibition with texts by Clara Fernández-Ladreda and María Concepción García Gainza), Pamplona, Government of Navarra, 1994.

Tarsicio de Azcona, Azcona de Yerri. El pueblo, su parroquia, sus ermitas, Pamplona, Lamiñarra, 2011.