5 October

lecture series

SANCTUARIES IN ESTELLA LAND

The Sanctuary of Codés: Art and Devotion

Ms. Pilar Andueza Unanua

University of La Rioja

It is not easy to know exactly when devotion to the Virgin Mary began in Navarre. If we pay attention to the documentary news that speak to us of churches or monasteries placed under her invocation, we can detect her increase during the X century, as well as her consolidation in the following century, as it happens in the rest of Europe. This is evidenced by the restoring action of Sancho el Mayor on the cathedral of Pamplona, insisting on its Marian dedication, and the construction throughout the 11th century of temples of great importance, sponsored by the monarchs of Pamplona, such as the churches of Santa María la Real de Nájera and Santa María de Ujué. The fullness of the cult of hyperdulia was definitively consecrated in Navarre in the 12th century, both with the collegiate church of Tudela and with the expansion of the Cistercian Order, a Marian order par excellence, with its monasteries of La Oliva, Fitero, Tulebras, Iranzu and Marcilla, all dedicated to the Virgin. A century later, at the behest of Sancho el Fuerte, the collegiate church of Roncesvalles was built, which, together with Ujué, would be the most significant Marian centers of the kingdom.

Between tradition and history: the origins of Our Lady of Codés

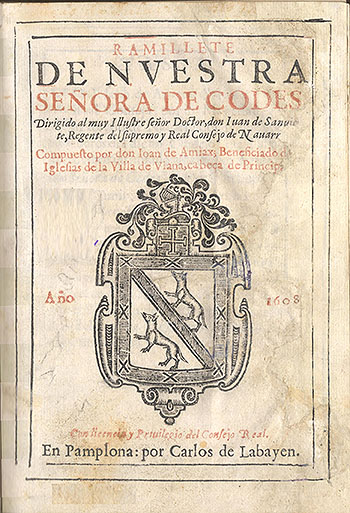

As is the case with most Marian images, the origins of Nuestra Señora de Codés and her devotion are uncertain. As tradition has been gathering for many centuries, its origin is said to be in the lands of La Rioja, specifically in the city of Cantabria. This is how Juan de Amiax, presbyter and beneficiary in Viana, narrated it in his Ramillete de Nuestra Señora de Codés (Bouquet of Our Lady of Codés), published in 1608. This book, in quarto, carefully edited, with 384 pages and a two-colour cover, became over the centuries a work core topicfor the propagation of the legendary origin of the Virgin of Codés and the expansion of her cult. In fact, the work would see the light of day much later in two new editions, in 1905 and 1933, by the Carmelite priest Eusebio de la Asunción and the priest from Torralba Fernando Bujanda, in both cases with shorter texts, adapted to the new times and new mentalities. From the original edition of 1608 other authors later drew from it, such as the Jesuit Juan de Villafañe, who in 1740 wrote the Compendio Historico en que se da noticia de las milagrosas, y devotas imagenes de la Reyna de los Cielos, y Tierra, María Santissima, que se veneran en los mas celebres santuarios de España (Historical Compendium in which news is given of the miraculous and devout images of the Queen of Heaven and Earth, Mary Most Holy, which are venerated in the most famous sanctuaries of Spain). Of the eighty-four most important Marian advocations that he collected from all over Spain, as far as Navarre was concerned, he focused on Our Lady of Roncesvalles, the Virgin of the Tabernacle in Pamplona Cathedral, Our Lady of Ujué and the Virgin of Codés. Certainly Ujué, Sagrario and Roncesvalles were of great importance to the Christians from the averageAge onwards, as the Navarrese monarchs demonstrated with their devotions and gifts. We do not know, however, that in those centuries Our Lady of Codés enjoyed such fame. In our opinion, Villafañe referred to it because it was during the centuries of the Baroque, when he wrote his work, that the image enjoyed great popularity, not only among the Navarrese, but also among the people of La Rioja and Alava.

Photo 1. Juan de Amiax, Bouquet of Our Lady of Codés, 1608.

In more recent times, and again taking up the news from Amiax, we should also mention Father Valeriano Ordóñez, who wrote in 1984 about the Sanctuary of Codés, as part of the collection Temas de Cultura Popular published by the Diputación Foral de Navarra. His most interesting contribution, however, corresponds to the news he gave relating to the 19th and 20th centuries.

With a fully scientific character and focused on the study of the historical-artistic heritage of the sanctuary, the Catalog Monumental de Navarra. Merindad de Estella II** (1983), directed by Professor María Concepción García Gainza, and Arquitectura religiosa del Barroco en Navarra ( 1998), by José Javier Azanza López. In both cases the History of Our Lady of Codés was very present. Sencillos apuntes sobre Codés, published in Logroño in 1939. The value of this booklet lies in the fact that it offers numerous documentary news taken from different books of the file of Codés, such as those of Visits and those of the Factory, Alms or Inventories, far from legends and traditions. On the other hand, for the study of the image of the Virgin we must cite Imaginería medieval mariana, published in 1989, by Clara Fernández-Ladreda.

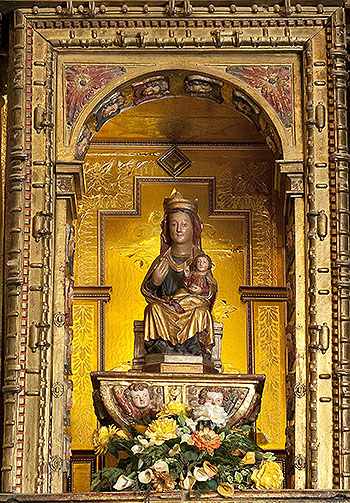

From agreementwith the aforementioned tradition, Juan de Amiax placed the origin of the image of Codés in the city of Cantabria, near Logroño. According to his account, in the year 575 the Visigothic king Leovigild attacked this enclave until it was destroyed, although some devotees would have taken the carving venerated there, together with numerous relics and bodies of saints, and placed it in the mountains of Torralba "because the land was so rough and mountainous" that it was safe. There, some time later - without specifying when - a small Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Lovewas found, completely covered with thorns, where the image of Codés was found, together with the bones of martyrs, a small green jasper altar and various ancient cédulas. In the light of reason, this origin is logically mythical, as the events narrated in the lands of La Rioja are dated by Amiax to the 6th century, while the image that today presides over the sanctuary is a Gothic carving from the mid-14th century, i.e. eight centuries later. However, member of the clergyfrom Viana does mention that a papal bull given in Avignon on 8 June 1358 granting indulgences was kept in the sanctuary, in which the devotion to the Virgin and the building of the sanctuary were entrusted, a document that would coincide in its chronology with the venerated image.

Photo 2. Our Lady of Codés, mid-14th century

The Modern Age, the golden age of the sanctuary

Despite these uncertain or legendary origins, it was from the Modern Age onwards that devotion to the Virgin of Codés seems to have increased, especially from the 16th century onwards, becoming an important centre of pilgrimage for the people of the Merindad de Estella, but also from the lands of La Rioja and Alava. Two events were fundamental to this, as narrated once again by Juan de Amiax in his work. On the one hand, the first miracle attributed to Our Lady of Codés and, on the other, the presence at the sanctuary of a hermit with a reputation for holiness, Juan de Codés, to whom he attributes the beginning of the blessing of cloths with therapeutic and curative properties.

The first miracle of the Virgin of Codés corresponds to a tradition that has survived to the present day and that year after year the brotherhood of San Juan de Torralba del Río commemorates on 24 June. Amiax narrates that in 1523 there were bandits near Cábrega, in the Berrueza region, who robbed and raided the villages in the area. They took refuge in the castle of Monicastro or Malpica and their leader was Juan Lobo. The villagers defended themselves through the aforementioned brotherhood which, at the ringing of the bell, gathered its members to pursue the bandits. On one occasion the bandits robbed a man and took him prisoner to the castle, imposing thick boards as shackles on him. While he remained there, the prisoner prayed to the Virgin of Codés, and so one day a miracle was worked: he appeared asleep at the gates of the Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Lovede Codés, where some shepherds found him and woke him up to hear his story. The shackles were hung there as an ex-voto and from then on there was a hermit in that place who, once the news spread, began to receive pilgrims, definitively starting the devotion to Our Lady of Codés. At the same time, the bandits were captured and Juan Lobo was killed by a spear thrown by the knight Mosén Pedro de Mirafuentes, a neighbour of Otiñano. It is precisely this legendary episode that the same brotherhood commemorates every year by chasing Juan Lobo. Logically, over time, as is typical of intangible heritage, religious elements (dawn, mass and procession) have been mixed with other festive elements such as dances and gastronomy.

Amiax places the figure of Juan de Codés in 1530, when he entered Codés as a hermit. He remained there for ten years attending to the faithful and pilgrims. However, desiring a totally eremitical life, he withdrew to a Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Lovelocated higher up: the Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Lovede la Concepción del Monte where he erected an altar for which he obtained the corresponding permission to celebrate mass, thanks to an apostolic brief, dated 30 November 1540 in Rome, a document that Amiax transcribes in his book. After seven years of contemplative life, Juan decided to go to Rome, with the aim of going to the Holy Land, although the Pope prevented him from setting sail in view of the corsair threats. When he returned to Navarre in 1547 and once again settled in his Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Love, he heard that Pedro de Bujanda, a young man from Torralba who had been wounded in the neck during a brawl in Logroño, had been taken to the sanctuary of Codés. Juan came to his aid and, after celebrating mass, blessed before the Virgin some linen cloths that he placed over the wound to form a cross. The young man's speedy recovery spread rapidly among the parishioners. From then on, the cloths of Codés became very famous for curing the sick and crippled.

Amiax devoted the fourth book of his Ramillete to narrating how these canvases were to be blessed, and he recorded in detail sixty-one healings of devotees who came to them in search of healing. In most of them he recorded the names of the persons, their place of origin and the ailment suffered. Only in a few cases did he give dates. Most came from towns in the Merindad of Estella, although individuals also came from other areas of Navarre, as well as from La Rioja, Alava and even further afield, such as Sos del Rey Católico and even Saragossa. Among those healed were people of all ages, children, young people and adults, and from all walks of life, including both religious and, above all, lay people, among whom we can distinguish some important surnames of the Navarrese nobility, such as Eguía, Vélaz de Medrano and Beaumont.

The ailments suffered were varied in nature: sores, ulcers, swellings, broken bones, blindness, infected wounds, crippling, pain, wounds caused by stab wounds and rotisseries, falls from roofs, walls or horses, stones, axe cuts, sickle cuts, thorns, crushing by a mill wheel, bites from rabid animals or victims of the plague of 1599. Some ailments are extremely curious, such as the young man from Gauna whose hand was ulcerated because the master had hit him on the palm, or Domingo de Aguirre, a neighbour of Genevilla, who stabbed himself with his own dagger in a fall.

As a result of these healings, the grateful devotees offered the Virgin alms: mainly money, wheat and jewellery, as well as votive offerings, either in paintings (showing the portrait of the person healed, the scene of the accident or illness) or in the form of the part of the body healed. Thus, for example, the inventory of goods made in 1664 included three hearts, two breasts, a leg and seven pairs of eyes. In 1721 María Josefa de Pedro, a native of Logroño, was offered to the Virgin of Codés to cure her arm, once the doctors had decided to amputate it. As she was healed, she gave the sanctuary a wax arm as a testimony of her healing. A painting of this votive nature, painted by Diego Díaz del Valle in 1793, is still preserved on the staircase of the hospice. It portrays María Luisa Acedo y González de Castejón, born in 1787 in Mirafuentes, and cured as a child, as the following registration attests: "Dª Maria Luisa Azedo / y Castejon, daughter of / Dn Diego Azedo / y de Dª Maria Concepcion / Castejon y Sarria / la ofrecieron sus Padres a Nra Sra / de Codes por ha / verla librado de / peligro en una en / fermedad de edad / de 3 años a 4" (Maria Luisa Azedo / y Castejon y Sarria / la ofrecieron sus Padres a Nra Sra / de Codes por ha / verla librado de / peligro en una en / fermedad de edad / de 3 años a 4).

The sanctuary experienced its period of greatest splendour during the 17th century, extending its golden age during part of the Age of Enlightenment. This is evidenced by the architecture of the sanctuary and its artistic endowment, as well as the increase in pilgrims and the growing receipt of alms and gifts. Thus, for example, in 1647, 612 robos of wheat were collected, rising to 874 in 1661, and reaching 1,264 robos in 1674, a year in which 784 loads of firewood were spent in the hospice, which speaks of an important presence of devotees. The number of masses ordered at that time is also an interesting indicator of the fervour towards the Virgin of Codés, with 4,384 masses in 1670.

In addition to alms in kind, the sanctuary received important donations in cash and even inheritances. Among the first were donors such as Diego Jacinto Barrón y Jiménez, as we shall see later, Juan de Arbizu, knight of Alcántara, who gave more than 7,000 reales in 1655, the Counts of Santisteban, viceroys of Navarre, who made a donation in 1658, and Francisco Añoa y Busto, archbishop of Zaragoza, a native of Viana, who sent 200 pesos in 1764. For her part, Catalina de Arandigoyen, a resident of Zurucuáin, left all her goods to Codés in 1649. And so did Sebastián Mongelos, inquisitor, canon of the Metropolitan of Burgos, a native of Sansol, in his will granted in 1677. The increasing receipt of money had already led the visitor of the bishopric in 1620 to order the construction of a chest with three keys.

The submissionof pieces of silver and jewellery to the Virgin to commend oneself before some important vital status, as well as in thanksgiving, were also common in the centuries of the Baroque. This can be seen in Codés. Already in 1664, an inventory of goods indicates that there was a gold chain given by the Marquis of Villena, three silver chains, crosses, rosaries, jewellery, rings, earrings, chokers, Agnus Dei, charms, a diamond cross, an enamelled jewel and an ivory cross. By then the sanctuary also housed a significant silver trousseau: a large cross, four chandeliers, three large lamps, acetre and hyssop, a averagemoon, four large and one small candlesticks, two plates with their cruets, two large crowns, one medium-sized and two small ones, a candlestick, a box, a censer, a naveta and ten patens. To these were also added various pieces donated by the devotees. This is the case of two silver vessels given in 1665 by the Jesuit Fernando Labayen, the pectoral offered by the bishop of Calahorra Gabriel Esparza in 1670 or the 200 ounce silver lamp carried by Francisco de Calatayud in 1675, sent from New Spain by his brother Jerónimo. In 1695, Manuel García Olloqui, from Los Arcos, before leaving for Lima, endowed the Virgin with an imperial crown studded with pearls and two golden chalices. In the 18th century, in 1708, the neighbour of Viana, Antonio de Florencia, gave a set of chalice, paten, plate, cruets and bell, all made of silver, sent from Mexico. In 1726, the Capuchin priest Miguel de Torralba brought from Rome a filigree silver cross with the Lignum Crucis and its authenticity, accompanied by a bull of perpetual jubilee. Finally, although outside the field of goldsmithing and jewellery, it is worth mentioning the organ given in 1728 by Francisco de Olite, a resident of Viana.

The decline of the 19th century

Towards the end of the 18th century, the statusde Codés began to change and by the end of the century, a decline began that lasted practically the whole of the 19th century. Thus we know that as early as 1795 the houses of the sanctuary were already threatening ruin. The year before, during the war of the Convention, the sacred vessels, jewellery and jewels were placed in an ark and hidden in the parish church of Torralba. With the Napoleonic invasion and the War of Independence (1808-1814) the sanctuary served as barracks for troops from both armies, with the consequent deterioration, and lost its silverware when it was requisitioned by the French on 6th November 1809.

The first Carlist war (1833-1840) had a great impact on the area, which became a theatre of war. On 26 December 1837, the liberal Martín Zurbano sacked the sanctuary of Codés, considering it to be a refuge for Carlists, and set fire to the inn. Once again, the third Carlist war (1872-1876) had a negative effect on the sanctuary. This can be seen in the words that the chaplain Simón Valencia wrote to the bishop in 1880: "If it were not for the tower that crowns the church, Codés would look like a building abandoned to the elements...; the rooms are in such bad use that they take away the traditional devotion of coming to Codés".

The revitalisation of the 20th century

The great revitalisation of the sanctuary of Codés came with the new century with the creation of the Cofradía Administradora del Basílica de Nuestra Señora de Codés, founded in 1901. Its aims were to promote the worship of the Virgin of Codés, to conserve its church and guest quarters and to ensure the sanctification of all its members, both members of the confraternity and its members. Just three years later, a large pilgrimage was held at the sanctuary in October to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception. Numerous events speak of the new impetus given by Codés: the minting of medals in 1905, the reprinting of the Ramillete de Juan de Amiax in 1906, the subscription for a mantle commissioned that year from the Trinitarians in Madrid on the initiative of Carmen Notario, a Navarrese resident in the capital, and the subscription made in 1908 for a crown for the Virgin and another for the Child, which were imposed in a solemn ceremony the following year. The decade of the nineteen-twenties was characterised by the start of the spiritual exercises led by the Jesuits, as well as by the works carried out on both the church and the guest house, which were inaugurated with great pomp and ceremony in 1920. In the 1950s, modern outbuildings were added to the stables by Víctor Eusa, and in the following decade a third floor was added to the complex. Recently, between 2007 and 2010, the Government of Navarre contributed to the last intervention carried out, which mainly affected the rear façade, roofs, enclosures and surroundings.

The construction process of the sanctuary

The present church of Nuestra Señora de Codés, possibly built on top of an earlier medieval Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Love, was erected in three construction stages throughout the Modern Age. At the end of the 16th century, around 1590, the first two sections of the church were erected, as can be seen by its star-shaped vaults. However, that space must have been insufficient for the growing devotion, and so in the 17th century it became necessary to enlarge the church. Two new sections were added at the foot of the church, in this case covered with two vaults, and a quadrangular chevet was erected over which a dome on pendentives overhangs. A sacristy was also added. The overall resultof both phases, as can be seen today, was a church with a single nave made up of four bays, with narrow side chapels communicating with each other, and a straight chancel.

Photo 3. Church of Nuestra Señora de Codés. Inside

These extension works, whose licencewas granted in 1636, were carried out thanks to various donations, including the 1,300 reals donated by the resident of Vitoria Pedro de Álava and, above all, the 300 ducats offered by Diego Jacinto Barrón y Jiménez. This gentleman was a perpetual almoner of the city of Logroño and through this alms he wished to thank the Virgin of Codés for curing him of a serious illness after having been given up by the doctors. A tombstone located at entranceof the church and dated 1643 bears witness to the generosity of this devotee and his wife Jacinta Fernández de León.

We do not know which artist carried out the work in this phase of construction. However, it is possible that the stonemason Mateo de Lamier, a resident of Torralba, carried out the work, as in 1614 he was enlarging the sanctuary house and in 1640 the accounts were being revised with him.

During the second half of the 17th century, various projects for the enlargement and embellishment of the building are documented. However, none of them were carried out at that time and there was no construction activity. Thus, for example, in 1661 in his visitto the sanctuary, Bishop Bernardo Ontiveros ordered the construction of a dressing room behind the main altar, "because the Holy Image has little capacity in the niche it is in". Although chronologically this is the first accredited specializationto be built in Navarre, the new space was not erected at that time and the prelate Pedro de Lepe insisted on the need for its construction again, again without effect, in 1695. The façade with portico and belfry, for which licencewas granted in 1686, was not built either.

On the other hand, during a good part of the 18th century, important works were carried out, especially on the chapel and the tower, which enveloped the church on the chancel and the Epistle side. We must place the starting date of this new construction phase - the third - in 1713, when the visitor of the bishopric once again ordered the construction of a chapel, a façade and, if funds were available, a tower. The stonemason Francisco de Ibarra was hired for this purpose. The work continued over time and by 1724 the tower had been erected up to the second section and the chapel had reached the level of the cornice. When Ibarra died in 1733, his widow handed over the work to another stonemason, Francisco de Sarasúa. By 1748 the chapel was finished, although the tower would not be definitively completed until 1761, as can be seen in an ashlar on its base.

With a quadrangular ground plan, the tower, of classicist character, has a prismatic shaft with a base and three sections, articulated by recessed pilasters and separated from each other by entablatures and moulded cornices. Each section opens to the front through openings that are treated in different ways. Thus, from bottom to top, there is a simple window framed by a flat band, another larger one with a lug frame crowned by a triangular pediment on corbels and, finally, in the belfry, a semicircular bay topped by a semicircular, avolute, split pediment.

Photo 4. View of the head and tower of the sanctuary of Codés

Of great interest, and totally linked to civil Baroque architecture, is the body that is attached to the church behind the chancel and whose interior corresponds to the old chapel, now converted into a sacristy. Its good ashlar construction belongs to the aforementioned eighteenth-century phase, which is why it is physically and stylistically linked to the tower. On the outside, it consists of two levels vertically articulated by means of pilasters. The lower level opens up through a triple frontal arcade that rests on sturdy pillars. The interplay of the segmental voussoirs of the semicircular arches stands out, giving the whole a great baroque style and plasticity. The second level is dominated by the wall. Rectangular openings framed by lugs open up on the wall, flush with the lower arches.

The sanctuary is made up of the church and an extensive guest house, called a house in the documentation. It is a vast building with an L-shaped floor plan and a horizontal layout that partially conceals the church. Its stone façade has three levels on which abundant openings are rhythmically arranged, as well as two semicircular entrances. It is physically and morphologically linked, forming an angle, with the body that houses the portico from which the church is accessed. The hostelry was built over the centuries, as documentation attests, although its current appearance is the result of the interventions carried out in the 20th century. Inside, the hallway and the staircase stand out for their 18th century Baroque models.

The altarpieces

The main altarpiece presides over the church and was consecrated on 2 July 1642. It dates back to 1640, when 400 reales were given to the aforementioned benefactor Diego Jacinto Barrón. His generosity had enabled the church and sacristy to be enlarged, and now he was responsible for bringing three large canvases from Madrid for the altarpiece, corresponding to the Annunciation, the Assumption and the Nativity.

The payments made in 1642 allow us to know the names of the artists who worked on this piece of furniture. The sculpture was made by Diego Jiménez de Castrejana, a resident of Cabredo, son of the Logroño sculptor Pedro Jiménez, who had trained in Valladolid with Gregorio Fernández. Diego was commissioned to carve St. Joseph, St. Joachim, St. Elizabeth, St. Anne and the two upper angels. The pedestal was made by Jerónimo Chávarri, a sculptor from Cabredo. Finally, the gilding was the work of Diego de Arteaga, a painter from Villava.

The altarpiece has a style typical of the first half of the 17th century, which Professor Fernández Gracia describes as classicist. During this period, Navarrese altarpieces were characterised by their hybrid nature, in which elements from the Renaissance, such as the balanced distribution and compartmentalisation of boxes and scenes, inherited from the Romanesque workshops, and other Mannerist and proto-Baroque elements, such as the wreathed columns, the progressively more fleshy decorative plant motifs in the friezes and the frames with abundant gadroons, can be found at quotation.

The altarpiece has a double bench above which rises a single body divided into three sections separated by wreathed columns. The paintings of the Annunciation and the Nativity are located in the side aisles, crowned by triangular split pediments. The central box, which houses the image of Our Lady of Codés, is finished off with a larger pediment that invades the attic and on which rest two reclining angels that evoke Michelangelo's Medici tombs. The whole is crowned by an attic between flutings and vases that holds a large canvas of the Assumption between twisted columns with a grooved lower third. It is crowned by a semicircular split pediment on which stands a Crucified Christ.

Photo 5. Main altarpiece

Iconographically, on the bench, flanking the tabernacle, we find two landscape canvases with Saint Catherine and Saint Barbara, as well as two angels and the carvings of Saint Joseph and Saint Joachim. On the second level of the bench are two reliefs of the Evangelists, associated in pairs and perfectly adapted to the architectural framework: St. Mark and St. John on the Gospel side and St. Luke and St. Matthew on the Epistle side. The high reliefs of St. Elizabeth and St. Anne flank the central painting of St. Coloma, an iconography that may be related to the devotion to this saint in the area - there is a Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Lovein Mendaza dedicated to her - as well as in the Rioja region.

In the central body, the image of Our Lady of Codés, much restored over time, occupies the main space. It is a seated Gothic carving, possibly dating from the mid-14th century. On either side are the aforementioned Madrilenian canvases of the Annunciation and the Birth of Christ. The attic has a pedestal on which are placed, in pairs, the Fathers of the Western Church: Saint Gregory and Saint Jerome on one side and Saint Augustine and Saint Ambrose on the other. The painting at the top of the altarpiece depicts the Assumption of Mary.

The main chapel is closed off by a magnificent three-part iron grille, partially gilded, which was commissioned in 1651 from Francisco Betolaza. This ironworker had his workshop in Elgóibar, one of the towns in Gipuzkoa where the best blacksmiths in the north of the country were based. With their grilles they nourished much of the Baroque religious and civil architecture in the Basque Country, Navarre, La Rioja and Castile. The grille was brought to Codés on mules and was installed in 1654, replacing an earlier one. The ironwork was gilded by Diego de Arteaga, who used 5,000 gold leafs.

The two collateral altarpieces, located outside the main chapel, were made by Bartolomé Calvo in 1654. They were finished a year later. They are twins and are dedicated to Saint Peter, on the Gospel side, and to Saint Anton, on the Epistle side. They consist of a pedestal, a single body with a central box flanked by paired Corinthian columns and an attic crowned by a semicircular pediment. The pinjantes, bunches of fruit, scrolls, cardinals and avoluted split pediments lead us definitively to the Baroque period, although they still have Classicist overtones. The original polychromy of the masonry stands out.

The altarpiece of Saint Peter narrates on the bench the submissionof the keys to Saint Peter between pairs of apostles and saints, in which their voluminous tunics and mantles stand out. The central niche holds a carving of Saint Peter, who carries a book and the keys, and in the attic his martyrdom.

For its part, the bench of Saint Anton presents various scenes from the life of the saint, such as his martyrdom, the death of Saint Paul the hermit, or some temptations, again among saints and apostles. The patron saint is a beautiful sculpture, dressed in a habit, with a book and a staff, in which the realism of his bearded face stands out. A relief of Saint Anton tempted by demons in the attic completes the ensemble.

Photo 6. Altarpiece of San Antón. Detail of the main altarpiece

bibliography

-AMIAX, J. de, Ramillete de Nuestra Señora de Codés, Pamplona, By Carlos Labayen, 1608.

-AZANZA LÓPEZ, J.J., Arquitectura religiosa del Barroco en Navarra, Pamplona, Institución Príncipe de Viana, 1998.

-GARCÍA GAINZA, M.C. and others, Catalog Monumental de Navarra. Merindad de Estella II**, Pamplona, Institución Príncipe de Viana, 1983.

- A.M.D.G., Historia de Nuestra Señora de Codés. Sencillos apuntes sobre Codés, Logroño, Cofradía Administradora del Santuario de Nuestra Señora de Codés, 1939.

-ORDOÑEZ, V., Santuario de Codés, Colección Temas de Cultura Popular nº 343, Pamplona, Diputación Foral de Navarra, 1984.