October 3

lecture series

PAMPLONA IN CONTEXT

Docomomo Buildings

Javier Torrens Alzu

Architect

Docomomo (Documentation and Conservation of Architecture and Urbanism of the Modern Movement) is an international organization, created in 1990, with the aim of "inventorying, disseminating and protecting the architectural heritage of the Modern Movement". The Docomomo Ibérico Foundation covers Spain and Portugal and has carried out its registry in several phases: first, 166 representative buildings in the period 1925-1965 and, in several successive phases, various sections have been documented: housing, industry and equipment, etc., until reaching about 1,200 works. Since 1997, biennial seminars and congresses for theoretical discussion have been organized. An Inventory of Spanish Architecture of the 20th century has been compiled, with some 6,000 entries at database. Activities are coordinated through the Associations of Architects of Spain and Portugal. In 2018, 38 Docomomo plaques have been placed in its scope, reaching a total of 242 since 2012.

In Navarra there are 19 buildings registered in both categories A and B. Recently the period considered has been extended to 1975 and, in Navarre, a significant issue number of new recognitions has been added (11 more buildings: nine in category A and two in category B). To illustrate this little-known field of architectural heritage, I will focus on nine examples, the most significant and accessible, eight of them in Pamplona and one in Guerendiáin (Ultzama).

The motto President of the Modern Movement in architecture was "Form follows Function "( FfF), which already appears in the writings of the architect Louis Sullivan (1856-1924), Frank Lloyd Wright's teacher. The concept Modern Movement was born later, in the exhibition that Russell Hitchcock and Phillip Johnson mounted, in 1932, at the MoMA in New York and was equivalent to the expression International Style and wanted to publicize the modern architecture that was being done in Europe before the emigration caused by Nazism. The FfF slogan was more a wish than a reality applied to architecture, which has always had an important content more formal and stylistic than strictly functional, unlike what can be seen in the field of engineering. Fundamental to this paradigm shift, which put an end to historical styles, were the technical advances in engineering applied to architecture: the steel structure, the elevator and air conditioning, which allowed architecture to free itself from previous formal corsets, reach great heights and have large glazed surfaces. This technical evolution is perceptible both in the engineering of the nine bridges that linked Manhattan with the other boroughs, as well as in pioneering European works of modern architecture such as the conference room operations of the Postal Savings Bank in Vienna (Otto Wagner, 1905), one of the most important milestones of reference letter in steel and glass architecture.

The allusion to Otto Wagner is relevant because his architecture was admired (in the travels of his early professional years) and source of early inspiration for the young Victor Eúsa who, in the 1920s and 1930s, designed and built important works such as the Vasco Navarra (1924), with a Wagnerian statue of Pallas Athena at the top (demolished in the 1940s when a penthouse was erected, topped by a neo-Herreran spire), the Misericordia (1927), with an equally Wagnerian chapel, the large expressionist concrete and brick residential building at place Príncipe de Viana (1929), the talking architecture of seminar (1931), or the corner treatment of the small house on Fernández Arenas (1932). But these buildings are not Docomomo, as the first recognized within the register is the Casino Eslava (Eúsa, 1932), on a corner of the place del Castillo, with large windows, terraces on the top floors, a copper facade on the porch and, above all, an interesting open floor plan with a beautiful helical staircase and many decorative elements on walls and ceilings that have been lost.

Casino Eslava.

The second architecture included in the Docomomo register is the CAM Housing building (Zarranz, 1934) on Paseo de Sarasate, built by a young Zarranz after a competition in which important architects such as Yárnoz, Alzugaray, Esparza, etc. participated and in which the clarity of the diagonal distribution of the floor plan and the rationality of the exteriors with curved windows and shutters and elegant sandstone cladding were valued. Zarranz, who died in the Civil War, had already built an interesting social club for the Larraina sports facilities (1933), later destroyed, which was inspired by the Nautical Club of San Sebastian (Aizpurúa and Labayen, 1929) and by the Central European rationalist architecture that Zarranz knew well.

CAM housing.

The third Docomomo building is the high school Vázquez de Mella (Esparza, 1934) by the architect who designed the 1920 Ensanche plan, a late layout similar to that of Cerdá in Barcelona, although with barely a hundred blocks of smaller dimensions (70x70m) than the original. The small school (for boys and girls) turns out to be a rationalist construction with a clean layout, large windows and an E-shaped floor plan that has allowed successive extensions (gymnasium and covered patios) without affecting the values of the original building too much.

The first fully modern work in Pamplona, homologated with the architecture that was considered reference letter, known through the work disseminated by architectural magazines, is, paradoxically, a hidden work: the Felipe Huarte House (Redón and Guibert, 1959) located within the Villa Adriana estate whose main building had been designed by Eúsa for the family. It is a work, registered in the Docomomo, the first of the successful tandem Redón-Guibert, which denotes a plenary session of the Executive Council mastery of modern language in the young architects. It is a prismatic Issue raised above the ground with walls that emerge from the ground floor to the outside, in the Miesian manner, and an organization of the interior space very much in the taste of the Nordic masters that their designers admired. Redón said that they had to design many elements that did not exist as standard.

The following buildings registered in the Docomomo belong to Redón and Guibert's most fruitful period. The Las Hiedras Building (1961) is our flatiron since, like the New York building, it is located at meeting between the orthogonal grid of the Ensanche and the diagonal (Avda. leave Navarra). It occupies the former garden of a mansion after whose demolition in the 70s (the first controlled blasting in Pamplona) the same Redón (with Sagastume) would build the building that overlooks the place. But the one that interests us is the first one, a triangular plan with two very well resolved houses and a different treatment on its facades, the main one to leave Navarra and the secondary one to Leyre. The corner treatment is as simple as it is effective and elegant. The architects used the same white ceramic tile that they had designed for Felipe Huarte's house.

Las Hiedras Building.

In the Klinker Club (Redón and Guibert, 1962) in Olazagutía, essay, some of the characteristics of his best rural works appear: an organic open floor plan on different levels, a rigorous structure, almost non-existent facades, mere functional enclosures and powerful roofs that constitute the formal character of the building. The materials are economical and the fluidity of the interior space is sought.

The Huarte Towers (Redón and Guibert, 1963) is a complex of 96 dwellings in two attached towers with four dwellings per floor, each one, which are organized in a rigid structural grid of 4.10 m on each side that is manifested on the outside in a concrete skeleton with yellow brick panels. Some modules are patios or bathrooms and others are displaced to house the stair and elevators. The soon to be obsolete domestic service areas caused internal reforms and the appearance of new openings in the facade that, in addition to the closure of terraces, somewhat distorted the balanced full-empty composition of the building.

The Erroz Tower ( Redón and Guibert, 1963) was erected on the site of the Erroz chalet, a small rationalist building that Eúsa had built in 1933 for one of the partners of the business that managed the cinemas in Pamplona. Situated in a privileged location on the edge of the park, the building presented a powerful formal image due to its fragmented top resulting from the height library assistant . With a butterfly-shaped layout, four apartments per floor, large elevator cores and staircases, the bedrooms open up in search of sunlight in a solution that Redón would later use in Ubarmin. The white limestone cladding, without overhangs on the windowsills, and the staggering of the top floors give the building a sculptural plastic quality in the city skyline.

Tower of Erroz.

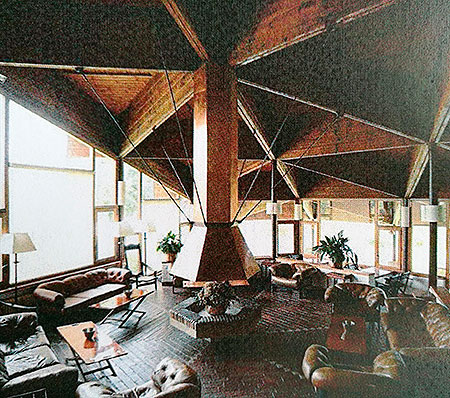

The most appreciated work of modernity in Navarrese architecture in the sixties, outside Pamplona, is the Ulzama Golf Club (Redón and Guibert, 1964). In a very beautiful forest landscape, the architects erected a complex and very beautiful building that opened to the outside as close to the ground as a large tile tent. The wood and steel structure supports the large continuous roof that extends over a space of great quality, organized on different levels of great complexity. The hexagonal structure of supports adopted (evocative of the Brussels Pavilion built by Corrales and Molezún in 1956) supports an expressive triangular structure of large-edged spruce beams. The result is an architectural masterpiece, merged with the forest landscape, combining a great interior spatial quality with a strong image and a subtle dialogue with the surroundings.

Ulzama Golf Club.

Ignacio Araujo and Juan Lahuerta formed another tandem of architects who produced, in those years, some examples of an architecture B for its rationalist elegance and perfect execution. The Library Services of the University of Navarra (1965) and the first phase of the University Clinic ( 1965) are white limestone buildings with a sophisticated and precise composition of openings. The first, a horizontal prism on an elevation, is presented as the face of an H-shaped floor; the second, a large white prism of nine floors, flanks Irunlarrea Street accompanied by a low body of access and administration that would be the germ of a large building developed later in several phases.

From the same year 1965 is the Casa de la Juventud ( Estanislao de la Quadra-Salcedo), the first endowment building for youth leisure in the Pamplona area. Very important in the cultural life of the seventies, it housed the first commercial initiative of Art cinema and essay in the city. Its rotund volumes on a two-storey base evoke images of Russian constructivism of the 1920s.

The initial period (1925-1965) of the Docomomo has been extended to 1975, which has made it possible to propose and obtain, this year, a good issue of additions in the two categories within the scope of Navarre. As mentioned above, eleven buildings were presented (nine in category A and two in category B). All of them were admitted to be part of the Docomomo registry. We highlight some of them:

The Ubarmin Clinic (Redón, 1968-75) is Redón's most interesting work in his solo phase, after his successful seven-year work with Guibert. Promoted by several mutual insurance companies as a Post-traumatic Rehabilitation Center, it is a large isolated building in Elcano, 9 km from Pamplona. The floor leave houses the consultation rooms and common areas in a 5x5m grid with landscaped courtyards. Above it rises the tower of rooms (180) facing south with the service areas to the north. A powerful concrete proposal rising above a vast sea of white plastic domes that completely covers the floor leave. A total work of art in the open landscape of the region with details of a careful design.

The Dining Halls of the University of Navarra (Echaide, 1968). A large roof shelters the diaphanous floor of glazed perimeter and gallery of the main space on a powerful base. A building with a factory appearance located next to the river Sadar, which is accessed by a small bridge.

The PPO Professional training Center in Burlada (Cano Lasso and Campo Baeza, 1974). A large building representative of the good work of the Madrid-born Cano Lasso, with red brick and a classic rationalist organization evocative of the formal clarity of the Dutch neoplasticism of J.J.P. Oud in the twenties and thirties.

Finally, the place de los Fueros (Moneo and de la Quadra-Salcedo, 1975). This is the excellent and timeless urban design , an urban hinge between the various parts of the city that converge on the site and brilliantly resolves both vehicular and pedestrian traffic. A public space is created with a sunken circular place and a sloping landscaped moon average as if it were an updated version of a Roman theater. Special attention is paid to the treatment of bone brick and to the visual references in the pedestrian accesses.