17 August

lecture series

AROUND THE ASSUMPTION. FEAST AND ICONOGRAPHY

The Virgin of the bed, a singular cult. Devotional and iconographic notes

Jesús Criado Mainar

University of Zaragoza

Beyond the modest presence of the Virgin Mary in the New Testament, the Church from an early date accorded her a singular cult due to her role as the Mother of the Redeemer, consolidated in the ecumenical councils of Nicaea (325) and Ephesus (431). The Death, Dormition or Transitus of the Virgin is only founded in apocryphal texts, although it was already well defined by the 3rd century and from that time onwards generated an extensive literature. The Eastern Church celebrated this feast as one of the most important in the liturgical calendar, and most of the early representations of it come from the Byzantine sphere, where it was known as Koimesis - literally, 'sleep of death'.

The spread of this iconography in Western Europe dates back to the 11th-12th centuries - although there are some earlier examples - and was consolidated with its incorporation into large French cathedral portals such as that of Senlis (ca. 1170), in which the Transitus of Mary is illustrated at leave with the ascent of her soul to heaven and her Coronation at the top. However, from the 14th century onwards in Italy, the Transitus was often accompanied by the passage of the glorious Assumption of Mary in order to incorporate the pious tradition that the Virgin gave her Sacra Cintola or girdle to Saint Thomas, who had not been present at the moment of her death, because the cathedral of Prato had kept this precious Marian relic since 1141. An example of this is the relief on the back of the tabernacle (1355-1357) of the high altar of chapel of Orsanmichele in Florence, a work by Andrea Orcagna. Whatever the case may be, it is certain that Italian art ended up opting for the Assumption rather than the Coronation.

As the 14th century progressed, altarpieces dedicated to the illustration of the different passages of the Virgin's life became more and more frequent, including her Transitus, sometimes even occupying the central compartment, as in the monumental altarpiece that Veit Stoss made between 1477 and 1489 for the high altar of St. Mary's in Cracow. This process came to an end in the 15th century, at a time when the Dormition of Mary took on an autonomous character to become a single subject, as in the Maria-Schlaf altar or altar of the Dormition of Mary (ca. 1434-1438) in Frankfurt Cathedral.

This growing development of the last medieval centuries reflects the effervescence that the Assumptionist cult had acquired, with a colourful liturgy centred on the festivity of 15 August that included different facets: from the ceremonies inside the church, which began the day before and in many places lasted throughout the octave, to the processions, inside and outside the church. And not forgetting the paraliturgies that staged in a theatrical - and therefore very visual - way the story of the death, resurrection and ascension of Mary to heaven, of which a precious trace still survives in the celebration of the Misteri d'Elx.

The Assumptionist cult reached a very special dimension at that time in some cities of the Crown of Aragon, including Palma de Mallorca, which has kept it alive to this day. The Balearic capital celebrated - and still celebrates - the Assumption with great solemnity, relying on an image of the sleeping Virgin or llit - bed - (documented as early as 1457, although the current one dates from around 1500) which was the centre of the liturgy from the eve of the festivity until the afternoon of the 15th, when it was taken in procession through the streets of the city. The same was done in other Aragonese cities, including Lérida, Valencia and Zaragoza.

In the City of the Ebro, the organisation of the feast of the Assumption of Mary was at position of the confraternity of Our Lady of the Miracle, which was part of the convent of Santo Domingo, and which held a small urban procession through the streets of the neighbourhood of San Pablo - where the Dominican monastery was located - on the day of the octave at least since 1498, but probably as early as 1485. From 1560 onwards, the ritual and the route were changed: the procession moved to the afternoon of the 15th and left the neighbourhood to go to the metropolitan church of El Salvador and the collegiate church of Santa María la Mayor y del Pilar - in the centre of whose titular altarpiece the Assumption was represented -, thus acquiring a greater solemnity to which the presence of the municipal council also contributed. The brotherhoods carried a processional pedestal in the form of a bed with a canopy, inside which a lavishly dressed image of the sleeping Virgin was placed, in the same way as in Palma de Mallorca, although here the image was not clothed.

This change was to have a great impact on other towns in the surrounding area, from Cariñena to Calatayud and Daroca, where in the late 16th century brotherhoods were founded - some of them made up only of women - dedicated to organising the celebrations of the Assumption and equipped with images and processional devices similar to those of the capital.

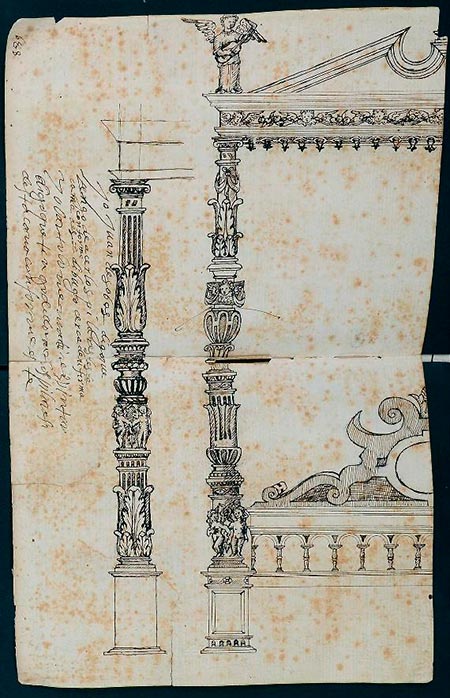

Cariñena. design cama de la Virgen.

Fortunately, in some localities they have been preserved, although in most of them the festival has been lost. Among the most interesting examples are those of Acered (Comarca de Daroca), Olvés and Munébrega (both in the Comarca de Calatayud), all three made in the early years of the 17th century and of clear Renaissance inspiration. They are a good counterpoint to contextualise the magnificent Virgin of the bed in the Museum of the Monastery of Nuestra Señora de la Caridad de Tulebras - in this case, the image is from the 17th century while the bed was made in 1784 - which is the most relevant testimony of this cult that has been preserved in Navarre.

Acered. Virgin of the bed, ca. 1610-1620.

Munébrega. Sleeping Virgin, ca. 1600-1610.