September 14, 2009

Global Seminars & Invited Speaker Series

THE CULTURAL HERITAGE IN THE VALLEY OF RONCAL

Tangible and intangible heritage in the Roncal cultural landscape.

Pablo Orduna Portús

International University of La Rioja

Today, in the context of the European Union, European populations, more or less isolated, need to assert themselves in a community context and, even more so, in a globalized context. To do so, they establish links with their past and their heritage elements that allow them to show themselves to be singularized at the individual and referential level. From the sociological point of view, it has become essential to redefine the equation of the 'self' versus the 'other'. In this endeavor, one analyzes, or at least tries to decipher, the meaning of one's own cultural fact, tangible or intangible.

In the Roncal Valley it is possible to appreciate how in this singular landscape the material and immaterial heritage converge in something socially and culturally unique and active. A multitude of megalithic monuments of common ancestors, hermitages or even trees of great antiquity can be found in the region... All of them stand out in the landscape as they are converted into 'landmarks' of a living and active reality. This becomes more interesting if we take into account the condition of peripheral and border region that the region has in the continental framework .

Gurevich (cit. Bottino, 2009, pp. 5 et seq.) asserts that the configuration of the world today is the result of the union of different fragments. In this way, its totality creates a mosaic that is not a simple sum of tesserae or parts, but the reflection of a latent dynamic. It is an evolution in constant articulation and decomposition that rearranges its structure, adapting itself to each historical and cultural moment. In this new socio-cultural environment, it is necessary to highlight what vision is held of heritage assets and what have been or are their misinterpretations in the populations. At the same time, it is necessary to establish new strategies for their dissemination that link them to the construction of the collective identity and the social development . However, for this it is necessary to redefine the concept of heritage and the paradigm of its intergenerational transmission. Thus, the heritage heritage as a whole is constituted in a Cultural Landscape only perceived in its polysemic integrity through a holistic view.

Tribute of the Three Cows. source Photographic collection Casa Txurrust (Uztárroz).

In the Roncal Valley, there is a heritage collage made up of a multitude of small remnants that end up composing a whole by means of a transversal warp. It gives the sensation that in each element that constitutes it there is 'something' that remains, that is transmitted intergenerationally. It is not a static fact but a 'living reality' in continuous evolution. It is true that it is presented as something perennial in space and time, but at the same time it is transformed at the same time in the individual and collective report . It assimilates changes and modifications without losing its ultimate meaning: to be a living element in a community of belonging.

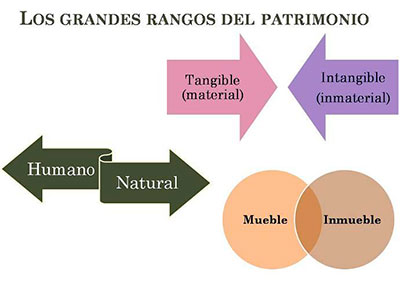

It is clear that the concept of heritage is articulated both by international agreements (UN Conventions and article 167 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, IUCN, etc.), as well as by national and regional legislative frameworks in the case of Spain. Already the Foral Law of Cultural Heritage of Navarra (2005), establishes that in the case of Navarra such heritage "is integrated by all those immovable and movable assets of value". Likewise, not only tangible assets are considered as such, but also "the intangible assets related to the culture of Navarre [...] which are part of the popular and traditional culture of Navarre and its respective linguistic peculiarities". In the context of Roncal, we can speak of heritage realities as disparate as funerary stelae, coats of arms, megalithic monuments or rituals such as the Tribute of the Three Cows. Thus, in its globality, a scale of protection integrated by BIC (Goods of Cultural Interest), BI (Inventoried Goods) or BRL (Goods of Local Relevance) is carried out. Within the POT 1 - Pyrenees (Territorial Management Plan) of the Government of Navarre, it is even proposed the consideration of new elements as heritage sites susceptible of being included in certain categories of protection: the urban nuclei of the valley, the Wayside Cross of Urzainqui, the Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Love of Idoia in Isaba or the Cañada Real de los Roncaleses (Royal Cattle Track of the Roncaleses) itself.

sourceown elaboration.

In parallel, in line with the above-mentioned central administrative measures, the local authorities themselves have promoted attempts to initiate new cultural elements in order to be declared BIC: the Uztárroz Wool Road, the Royal Road of the Valley, the Route of the Swallows.... If this has not been achieved, local measures have been carried out for their conservation and restoration with a subsequent diffusion... An example of such actions can be the rehabilitation in auzolán of the old furnace of the Isaba weaving mill.

In this Pyrenean valley, the natural landscape becomes a magnificent setting for heritage events. It is a place of ethnological, historical and artistic interest that houses a set of movable or immovable elements that bring together all subject constructions or facilities linked to ways of life, culture and traditional activities of the people. Now, within the heritage fact, all its representatives contribute a significant value; that is to say, they gather characters that have recognized interest or relevance for the culture of their people. This allows them to be interpreted by the inhabitants of the place of agreement with criteria that constitute them as testimonies of an epoch or a concrete stage of their civilization. It is there where many of the already mentioned transversal examples appear: the traditional clothing and its relation with the trades or social status; the sculptural or pictorial manifestations -artistic or artisanal- and their link with the religiosity or the mythological beliefs of the environment, many samples of traditional knowledge that speak of a way of life rooted to a specific ecological niche, customs, rituals and traditions that express a relation with the past interpreted from the present...

TTunttun dance. source Own elaboration.

It can be said that the tangible heritage is the most easily perceived as a visible element of the cultural heritage of the Ezka Valley. It is a tangible expression through material 'great achievements', thus bearing witness to the existence of a culture and its vision of the world. It represents a witness of their way of life and their way of being by remaining bequest intergenerational. It is necessary to value it in the measure of its own material wealth, but also from the exercise that a subject of that community -or the complete collectivity- performs when interpreting its importance. They are values understood as attributes granted either at an aesthetic level or in the Degree of its symbolism. This gives them an active component as individual landmarks representing values expressed by a society. At the same time, they have a collective reason as a heritage ensemble of a valley, which is actively manifested as identity expressions of a culture. In this Pyrenean valley, the collective identity and report have been a consubstantial part of its own differential conception. This is observed in that other great block of cultural heritage which is the immaterial. A series of facts that are not palpable -and sometimes invisible- but real and lived. All of them reside in the spirit of Roncalese culture and have often concentrated their traditional knowledge or know-how. Such a list of realities has been transmitted by oral literature and by participant observation that agglutinated different generations in a singular 'way of life'. Thus, reference letter is made of social rites such as the Tribute of the Three Cows, idiomatic constructions such as the Roncalese dialect of Basque, the ethno-phytonymic knowledge of the local flora or the old trades of almadiero, transhumant shepherd or various craftsmen.

Day of the almadías (Burgui). source Pablo Álvarez Vidaurre.

In final, we can speak of a 'living human treasure' that gives meaning, usefulness and transmission to the whole heritage. In the valley we can see how its people keep it active by recreating and reinterpreting it freely according to their interaction with nature, their neighbors and their history. Only its safeguarding will guarantee the sustainability of the cultural diversity of this community in Navarre and many others in the Pyrenees. It is a living heritage because, even today, it retains its usual place in the space within which it fulfills certain functions for which it has been created or modified in the historical and anthropological course. If it no longer had its meaning or its raison d'être for the local population, it would have become a museum piece or an academic case study, no less valuable for that reason. Territory, report and community make it the engine of local development and an active contingent in the definition of cultures such as the Roncalese. It can be pointed out that it acts from a socio-cultural projection in local initiatives that makes it sustainable in the face of the challenge of guaranteeing its cultural expression as something specific, not acculturated or globalized. There is a real will not only to preserve it, but also to recover it, also with a community resilience capacity to overcome losses in the past, to observe its current role and its future function as an element of local construction and development .

Sources cited

Bottino, M.ª R. (2009). On limits and borders. Rivera - Santa Ana do Livramento. programs of study históricos - CDHRP-, 1, 1-18. Retrieved May 18, 2015, from http://www.estudioshistoricos.org/edicion_1/maria-bottino.pdf.