12 August

lecture series

CASCANT

Symbols and attributes in the construction of images: examples in Cascante

Ricardo Fernández Gracia

Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

The possibilities for learning about cultural heritage are numerous: the recreation of daily life in a monastery, in an urban center, in a palace or next to objects of daily life, or showing the sponsorship of the privileged elites in a cathedral, the arrival of formal influences through routes, roads or personal interventions, etc... etc. As a common denominator, it is always desirable to insist on the global vision of cultural heritage because of its condensing character, since, in its day, when it was conceived, literature, music, liturgy, protocol, architecture and figurative and sumptuary arts coexisted in a harmonious and integrating way.

Looking, seeing and reading through cultural heritage can be a profitable exercise when it comes to making readings in core topicof numerous cultural sites from the past. We know texts by Lope de Vega or Fray Hortensio Paravicino and other writers in which the difference between the act of "looking" and "seeing" is pointed out , attributing to the mass of the population the inability to pass from one stage to the other, understanding the perception of works as a true intellectual act that required the capacity for judgement and discernment, which was forbidden to the majority of the public. With regard to "reading", Lope de Vega, when dealing with a biblical episode, stated: "In an image I read this story", and Father Sigüenza, when referring to a painting by Bosch, asserted: "I confess that I read more in this panel..., than in other books in many days". The challengefor today's scholar and citizen is to make plausible analyses and readings of images produced in a context so different from today's and with codes so far removed from our own time.

Canvas of the medical saints Cosmas and Damian, c. 1630.

Everything related to the construction of the images and their iconographic characterisation by means of collective or personal attributes is of enormous interest. An exercise in this sense and through the images of past centuries preserved in the different temples of the town of Cascante, provides an opportunity to reflect on the condensing nature of the heritage to which we have alluded earlier. The analysis of the Gothic carving of San Pedro or the Baroque canvases bequeathed by Andrés Urzainqui in 1671, the paintings of several Immaculate Conception, or the photographs of the Romanesque reliefs of the missing main altarpiece of the Assumption, provide the opportunity to analyse a number of issues which are often ignored, leaving their messages more or less hidden for lack of time and for having lost those codes of reading which are no longer those of our time, but which are indispensable for their correct interpretation.

The role of textual and graphic sources can also be seen as a substantial part of the creative process. In other works preserved in the church of La Victoria, such as the altarpiece of Saint John the Baptist, executed at the dawn of the 17th century by the prolific Juan de Lumbier from his workshop in the city of Tudela, we were able to analyse the texts and engravings that inspired his paintings.

With the help of an unpublished text written in 1785 by the Tudela historian and archivist Juan Antonio Fernández, with very interesting reflections, we were able to delve into the iconographic and aesthetic aspects of the disappeared main altarpiece of the parish church of La Asunción.

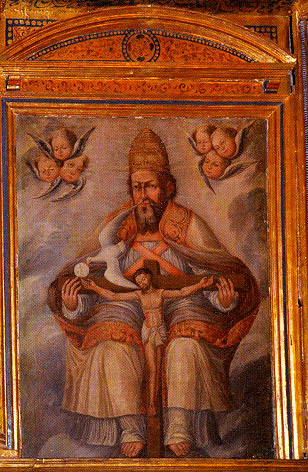

Holy Trinity in the main altarpiece of the church of La Victoria, first half of the 17th century.

The explanatory texts by the painter Diego Díaz del Valle for his opus magnum in his city, the decoration of the chapel of the Cristo de la Columna, were an opportunity for the artist to develop his more intellectual side, and even to show his academic training, typical of a master of the late Enlightenment who proclaimed himself to be a "professor of painting". He gives an account of all this in his written account of the ensemble, in which he expressed all his knowledge and understanding for the decoration of the chapel (1799), in what we might call "the artist explains his work". There he states: "It is not possible for all those who come to see the precious things invented by art in the primitives of painting to penetrate the ideas of a teacher in the decoration of his works. The former must be appropriated to the subject or object of the latter, and the latter must be executed in a place proportionate to the suitable expression of the former, as Vitruvius, the learned Leon Bautista Alberti and the famous Vicencio Carducho foresee. But what happens in this type of work? Executed by a professor with the greatest care, at the cost of pains and study, and with scrupulous attention to the rules of his School, the most idiots believe themselves authorised to judge of their proportion, of their propriety in ideas, of their taste in ornamentation, and not a few criticise them as they please: but few understand what they see, and almost all censure them at their own discretion. In the worthy weighing of those who pass in this, I certainly reject as judges those who, with no other rule than their whims, their unchosen taste, and their no aptitudefor graduating the dainties of a brush, deserve only contempt in their censures; and I wish only to attend to a simple idea of those which I have had in the arrangement of the decorations of the chapel of the Most Holy Christ of the Column, and of each of its parts, for the intelligence of those who, with sane and devout intention, wish to know what is the meaning of the various figures which adorn it. Without this clear explanation they would register it without light: and without this light, not only would they not be able to raise their imagination to the figurative, but even many would conceive some ideas very Materials (so to speak) and alien to reason and faith".

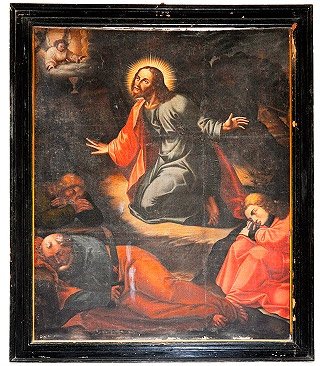

Canvas of the Prayer in the Garden bequestby the painter Andrés Urzainqui in 1671 for Cascante.

In the aforementioned architectural complex, Díaz del Valle painted an extremely important set of allegories, as it was the most numerous in that subjectof symbolic representations in Navarre. Cesare Ripa's knowledge of iconology must have been fundamental when planning the ensemble and its parts. The pendentives depicted obedience, innocence, humility and pain; the sides depicted constancy, contemplation, gratitude and devotion; while the centre depicted the allegorisation of the city of Cascante "in the form of a heroine glorying in the chapel", together with liberality. In the shell of the orange averagewere given quotationthe pillar of cloud and fire that guided the Israelites, the loving pelican, Caleb's grapes brought by Moses' envoys, Gideon's fleece, the subcinericean bread, Jacob's ladder, the lamb of the Apocalypse and the Ark of the Covenant.

Unfortunately, all those paintings were whitewashed and cannot be seen today. The two large paintings on the sides of the chapel have survived and can be compared with the descriptions of their author, the aforementioned Diego Díaz del Valle. One is described as follows: "On the left side, in another canvas, the Lord is depicted after being scourged at the Pillar, crowned with thorns, dressed in an old purple garment, with a reed in his hand for a sceptre as a King of mockery; and presented as such, as humiliated and tormented as Pilate exposed him to the people, when, to excite their compassion, he called their attention with these two mysterious words: Ecce Homo. May the Lord grant that the same words, placed on this canvas, may now excite in the hearts of the faithful the fruitful feeling of what the loving Jesus suffered for our sake, as these two canvases remind us, and as the four Evangelists tell us". To the second he dedicates these lines: "On the right side, the Lord is represented in a large oil painting, praying in the Garden to his Eternal Father, sweating blood with lively apprehension of his bitter Passion, and comforted by an angel in his anguish; On one side are seen the three sleeping disciples, and on the other the unfaithful Judas, who, coming to the Lord with the pretended kiss of peace, gave the noticeto the ministers and soldiers so that they might seize Him, who, in fact, threw themselves upon the most meek Lamb, as soon as they knew Him by the salutation of the infamous disciple, which was gradeon that cardwith his own words: Ave Rabbi".

Canvas of the Mother of Sinners, according to an engraving by A. Sellent, of the aforementioned Marian invocation of the Missionaries of the Congregation of Barbastro.

Finally, we made a brief analysis of the Baroque-era votive offerings preserved in the basilica of Romero, which gave us a good reason to consider some aspects of daily life, illnesses, clothing, as well as the beliefs and values of the society of the Ancien Régime.