5 June

lecture

Music and daily life in the Royal Collegiate Church of Roncesvalles

Ricardo Fernández Gracia

Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

Julián Ayesa

organist of Pamplona Cathedral

presentation

The history of Roncesvalles, the reconstruction of what it meant in the medieval culture of Navarre and Europe, is known thanks to the studies of different specialists. As in other cases, what happened in the centuries of the Ancien Régime has gone more unnoticed, despite the fact that there is an abundance of news on the collegiate church's file and many were published in Javier de Ibarra's monograph, rich in data but with few references to the documentary sources used. An enormous and complex heritage continued to be administered from Roncesvalles.

Daily life went on with repetitive rhythms and was punctuated with the festivities of spring pilgrimages and a renowned commemoration, in September, in honour of its patron saint. The course of the year saw rewards for wolf and bear hunters, and succulent banquets for the illustrious visitors who were not lacking in a place of passage and frontier.

Through music, some themes from the ordinary and extraordinary life of the collegiate church were chosen for this session in order to reflect them in the incomparable framework of its church, with the help of some melodies selected ad hoc.

Regarding the chanting of the canonical hours, from the end of the 16th century, the decrees of the Council of Trent and Milan were followed. Subprior Juan de Huarte states:

In Roncesvalles the whole official document is sung in firm chant, called in the vulgar "plain chant" and with a large and sonorous organ, well played, because they always look for a dexterous official. Figurative chant is not sung, which is a chapel of voices, because there is no possibility and because the Catholic Church has more C the former, which everyone must know, even if they are dignitaries, and they must sing on pain of not earning distributions in conscience.

At the beginning of the 17th century there were four infants, also called "mozos de coro", who interpreted the verses and attended matins, in pairs each week. They helped at mass and also served in the sacristy. It was considered appropriate that there should be six of them, so that four of them could devote themselves entirely to singing along with the racioneros, and they were required to know plainchant and organ.

The Constitutions of the chapter, published in 1791, indicate that the organist was generally the chapel master, and that a layman was the organist. The organist had the duty of playing the organ at convent mass, vespers, compline, daily salve and matins and, of course, at all solemn and extraordinary events. His position was responsible for distributing the scores and taking care in their execution, ensuring that the words and music were in keeping with "the majesty of the church", an expression very close in content and form to what the Marquis of Ureña wrote in his Reflexiones sobre la arquitectura, ornato y música en el templo (Reflections on the architecture, ornamentation and music in the church), published in Madrid in 1785.

As for the musicians, they were subject to the orders of the maestro de capilla, the prior and his chapter. The infants, under the jurisdiction of the chapel master, were to be instructed in music with morning and afternoon classes. They also received 18 robos of wheat, six ducats, clothing and firewood, and lived in their own house, belonging to the collegiate church.

The organ is described in 1587 with its registers of octave flute, fifteenth, sixteenth and sixteenth notes, flute, dulzainas and tremulant. In the twenties of the 17th century, Pedro de la place made a new one, which was considered a great instrument at the time. The same master contracted an organ for Cáseda in 1624. The lists of organists were published in his study by M. C. Peñas.

Winter rigours that led to the idea of relocation / Vivaldi's Winter

Roncesvalles under a large layer of snow (November 2015). Photo: Jesús Caso. DN.

A popular saying from the beginning of the 16th century was: "Roncesvalles, eight months of winter and four months of hell", in reference to the severity of the climate. The written sources mention the "strong winters and sad summers". The Navarrese doctor, Martín de Azpilicueta, reported that the sanctuary was "among its deserted peaks (of high mountains and crags) covered with grey clouds and white snow, with extreme cold and harsh ice and thick, damp fogs". Various documents bear witness to some historical snowfalls; among them we must mention the one in 1600, which was responsible for the collapse of the old cloister. In that year, 19 palms of snow were measured with a spike in Ibañeta.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the winters are described as "almost intolerable, due to the harsh inclemency of the region, with cold, ice and excessive snow that usually lasts until the month of May and some years until San Juan". Regarding the summers, mention is made of "the calamity of the fogs, where twenty days and a month are usually spent without seeing the light of the sun, oozing such strange humidity that they force us to stand over the fire, when elsewhere they burn with heat". The aforementioned sub-prior Juan de Huarte affirms that life in common was very difficult in those circumstances, and the refectory could only be used in summer, since the rest of the year it was necessary to eat by the fire,

because there are usually so many snowfalls that, as the houses are almost next to the church, it is not possible to reach entrance, as all the alleys are closed, and the snow goes up to the windows, which in such storms serve as doors for the church, as has happened this year 1616, and the biggest problem is not being able to get water, because it closes all the fountains and streams as with a wall and stagnates the mill, and for lack of water the snow melts in boilers and pans for drinking and service, the other, the download roofs because with the excess weight it would sink the houses, as has happened many times and as it sunk the cloister in the year 1600, breaking all its columns and arches, the repair of which will cost more than 16,000 ducats.16,000 ducats.

In 1622 and 1623, snowfall made the roads impassable and the canons were unable to go to church, having to continually download the roofs of their houses to prevent them from sinking.

The inclement weather was also reflected in the lightning of the storms. One of the biggest storms referred to in the texts was that of 2 September 1617, at five o'clock in the afternoon. group There was some personal misfortune in Burguete, when, faced with the stone and the heat, a group of five men, two women - named Dominica and Inés - and a pair of oxen with a cart of firewood took refuge under a large beech tree. As they were about to return to the village, a clap of thunder shook Roncesvalles and Burguete and a bolt of lightning that is described as "of bright fire that had set the buildings alight, causing terrible fear and fright" struck the tree and killed the two women and the oxen.

All these climatic rigours and the frontier location, which did not allow for the quiet and seclusion of a religious community with a regular life, led to the idea of moving the chapterhouse to the interior of Navarre, something that was not done due to the great expense that the construction of the architectural complex would entail. However, there was also speculation about asking the king for one of the "sumptuous palaces" of Olite or Tafalla, endowed with numerous buildings, arguing that for the monarch they were nothing more than expenses, or moving to San Salvador de Sangüesa. In that case, the hospital would remain in Roncesvalles with a canon and another cleric, with the staff to attend to the institution and a village with natural inhabitants with its mayor, all subject to the prior and chapter wherever they were.

The legendary: from Roland to the apparition of the Virgin and a famous reliquary / Echo of the valley by José Mª Beobide

Drawing from 1617 included by graduate Juan de Huarte in his Historia de Roncesvalles. Library Services Navarra Digital, a copy from the Library Services of the Collegiate Church of Roncesvalles.

The full-page drawing, which incorporates the manuscript history of Roncesvalles written by graduate Huarte between 1609 and 1624, is a graphic test about a context and a vision of the collegiate church's past at the beginning of the 17th century. It is dated 1617 and painted in pencil with coloured watercolours. It bears three coats of arms and an inscription in Latin, the translation of which is: 'These three insignia are more resplendent than the sceptres of kings, because they represent the trophies of the holy faith and the sacred laws'. The first of these depicts the Virgin on a throne of Renaissance ancestry, a copy of a 16th-century Marian engraving. At her feet, a kneeling pilgrim kneels in commendation and is being stalked by a pair of wolves, which dates back to the founding of the hospital in the second quarter of the 12th century. The second coat of arms shows the chains of Navarre and the green cross of the collegiate church, emblems of the kingdom and of Roncesvalles. The third is more complex and depicts two ivory cornets, the larger one of Roland and the smaller one of Oliberos; next to them are two maces, Roland's Durindana sword, "which the King of Spain now has in his royal armoury", according to the author of the manuscript, and the stirrup of Archbishop Turpin. All these objects have been on the main altar of Roncesvalles for centuries among lamps and have been visited by French knights, ambassadors and other persons of rank who "bring them down and venerate them by kissing them, and I have seen some of them weep with tenderness at the mere report and representation of such illustrious and ancient things".

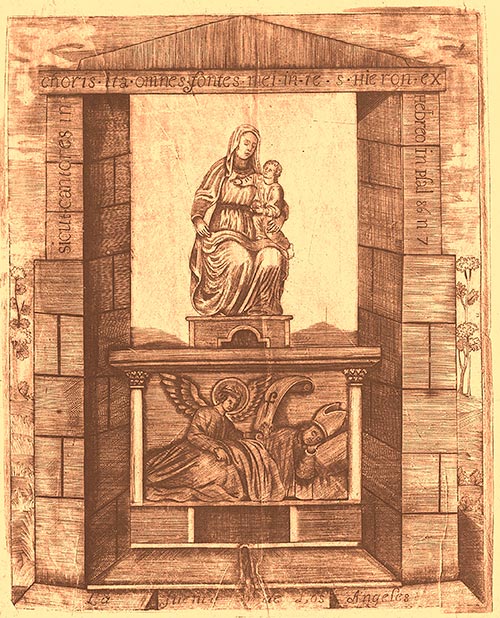

Everything related to the legend of the apparition of the Virgin was written down and even published, a fortiori, when Father Villafañe included it in his famous work (1740) on Spanish Marian images. But already in the 17th century the canons Huarte and Burges dealt with the subject topic. The former, taking information from the old canons and the description of some very old paintings in the cloister of the church of Sancti Spiritus, recreates the passage in the source with the deer with its luminaries on its antlers, the angels singing the salve and the peasants who listen and come, a little before Queen Oneca, who had the image covered in silver. Martín Burges y Elizondo adds the detail of the presence of the bishop of Pamplona, warned of the apparition by an angel while he was asleep; a drawing of the event at the source de los Ángeles can be found in his manuscript work.

source de los Ángeles con la Virgen de Roncesvalles in a drawing from the manuscript work of Martín Burges y Elizondo, c. 1670. Library Services Navarra Digital, a copy from the Library Services of the Collegiate Church of Roncesvalles.

As if all of this were not enough, some legendary relics, always at the height of the sanctuary, were collected in the so-called Charlemagne's chess set, a piece from the mid-14th century from the workshops of Montpellier which, according to the chronicle, were collected by Don Francisco de Navarra, prior of the house and future archbishop of Valencia. Some of these distinguished pieces were displayed in a reliquary cabinet in the chancel of the church until well into the 20th century.

Pilgrims of various kinds / Improvisation of Dum pater familias, Libro Vermeil Montserrat and Cantiga of Alfonso X Wise

Again it is Juan de Huarte, trained at the University of Salamanca, who at the beginning of the 17th century and with decades of experience as a canon between 1598 and 1625, provides us with an accurate description of the pilgrims who came to the collegiate church and its hospital. Specifically, he distinguishes four types. In the first, he includes the real ones, but warns of the great difference between the old ones and the new ones.

and those of these times, because the ancients, as true Christians and zealous for the salvation of their souls, made their pilgrimages in a holy manner, moved by holy ends, with proportionate means to achieve them, some for penitence for their sins, others to venerate the pious places in which God had shown his mercies in aid of the faithful and confusion of the unbelievers, working miracles; others for honouring the Virgin Mother of God, the holy apostles, visiting their tombs and relics, and those of many other saints, and above all that of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem with the other places sanctified by the presence of Christ our Lord. I well understand that in these times there will still be many pilgrims who will make their pilgrimages for some or all of these holy purposes, but they are very rare.

In the second class he includes vagabonds, idlers, wastrels, useless, bad workers, vicious people "who are neither for God nor for the world" and banished from their lands. With a average sotanilla, a slavina, zurrón, calabaza and bordón, together with a partner, pretending to be married, "they travel all over Spain, where they find people more charitable than in other parts of Christendom". In the same subject he lists those who spend their whole lives under the title of captives, deceiving simple people with tales of what they suffered in Algiers, Constantinople or Morocco, in the lands of the Turks and Moors, always pretending a thousand lies.

The third corresponds to farmers who come from France and northern Europe. Remember that, if they come from Bearne, they never indicate it, stating that they are from the Christian lands of France. They do not come for the true purpose of pilgrimage, but only to support themselves in Spain and accompanied by their wives and children. He identifies them as farmers who, once the sowing season is over, because they do not want to spend money on their houses or do not have any, dedicate themselves to singing couplets and songs until harvest time. In this same section he brings together the French hawkers, known as "merchants", "a very bright people like nettles among weeds, among Christians they are Christians and among heretics, like them". They are accompanied by bells and rattles and with pendants around their necks full of charms and ballads.

Lastly, in fourth place were the most pernicious "because they were heretics", both principals and commoners; the former, moved by curiosity to see Spain, because of their status as spies in times of war and disguised in the habits of friars and with staffs and slaves, never entered the church or took off their hats in front of the temple, and if they did it was out of mere curiosity, "to see the antiques of Roland and Oliberos", simulating Christian ceremonies to take refuge in the hospital. The latter were many and from different groups: labourers, cavacequias, paleros, guadañeros and stockbreeders, generally from Béarn, who came to Castile and Aragon. When they had finished cutting the hay, they returned home with the money they had earned. Both on the outward and return journeys, they stopped at Roncesvalles, where they received rations at the hospital.

Amidst the tolling of bells / In the garden of a monastery, Ketelbey

The ordinary life of the house, as in any village or monastery, was governed by the clock and the bells, which were under the supervision of the same person at position . At the beginning of the 17th century, it was stipulated that the individual should be instructed in ringing the bells in their different tolls corresponding to fires, holidays, semi-dual, double and solemn feasts, distinguishing also the mortuary, anniversaries, processions, ringing more or less quickly and with different times, "according to the quality of the feast and of the act". Apparently, all this had never been taken into account in the collegiate church, as the official document had been linked to the sacristan, who was quite busy with other divine worship duties. The knocks were also delegated to the boys and "although they are very large and loud, there is no rule or order in their knocks or differences". In those post-Tridentine times, there was a desire to be on a par with cathedrals, collegiate churches and other important temples.

The ancient tradition of the house, probably with medieval roots, of ringing a bell "by weight" for a while after nightfall and leaving matins to warn all the residents of the collegiate church to go home, closing their doors tightly, "because of the solitude and great passage of that place", was also taken up. The custom, which had fallen into disuse, was put back into practice at the beginning of the 17th century. Evoking the night in the surroundings of the collegiate church, with no light, total silence and the bell tolling, cannot fail to be awe-inspiring.

The Constitutions of the chapter of 1785, published in 1791, foresaw that all matters concerning the bells were to be handled by position by the minor sacristan and his servant.

The Ordinary: Hunting Bears and Wolves / The Great Battle of Marengo, Anonymous, c. 1800

The protection of pilgrims in the collegiate church - from enemies, inclement weather, bandits and wolves - is at its very origins and was a concern throughout the ages. The chroniclers relate that, with the foundation and endowment of the hospital and church of Roncesvalles around 1127-1132, the aim was to prevent the death of pilgrims from snowstorms and wolf attacks. To attend to them, the bishop of Pamplona, Sancho de Larrosa, founded a house for the reception of pilgrims and the needy. During the reign of García Ramírez, in 1135, it experienced enormous growth, ceasing to be a small hospital.

In the visit made to the collegiate church in 1590, during the period of full application of the Tridentine reform in the diocese of Pamplona, the Visitor Don Martín de Córdoba noted that in the time of lambing of sheep and goats it was necessary to take extreme precautions, "bearing in mind that many lambs have been lost and killed in this time, and at this time much damage has been done by wolves and wild beasts".

Two images have been preserved in relation to the harassment of pilgrims by wolves, both from the 17th century, in a relief of the dismantled main altarpiece that was exhibited at the sample dedicated to Huellas de la ruta. Arte en el Camino de Santiago en Navarra (2004) and in a devotional print of the Virgin of Roncesvalles.

With regard to the altarpiece, we should remember that its construction must be contextualised with the transformation of the main chapel of the church that took place under the priesthood of Don Juan Manrique de Lamariano, between 1619 and 1628. Its authors were Gaspar Ramos and Victorián de Echenagusia, both from the Sangüesa workshop, who were paid from 1623. Fermín de Huarte was in charge of the polychromy, and received 750 ducats for his work.

Relief of the main altarpiece of Roncesvalles, by Gaspar Ramos and Victorián de Echenagusia, 1623.

One of its panels, preserved in the collegiate church, depicts the Virgin and Saint James as protectors of pilgrims. The relief was located in one of the side streets of the altarpiece's attic. The shepherds are harassed by two wolves, even biting the younger one on the arm, while two of them try to scare the animals away with sticks. The presence of this image on the altarpiece, which attracted the attention of all those who entered the church, must have had a great impact, intensifying the stories, some of them legendary, that were told along the Pilgrim's Way to Santiago de Compostela.

With regard to the engraving, the scene of three pilgrims harassed by three wolves trying to reach the Pilgrims' Hospital appears in the lower part of the print made for the Virgin of Roncesvalles by Nicolás Pinson, a Valencian engraver born in 1640 and who died after 1672.

In provisions compiled in 1718, it was stated that whenever a hunter came with cubs of wolves, bears or their skins, he would be given two loaves of bread and two pints of wine, with the warning that if the canon hospitalero gave him two reales first, he would not be given anything else. These rewards were given provided that the calves or skins they brought had been caught within two leagues around the collegiate church. In the 1713 accounts, 8 reales were recorded to those who killed a bear in Ibañeta, 22 reales to a man from Abaurrea who brought three cubs of bears, 10 reales to one from Aézcoa who brought four cubs of wolves, 2 reales to another from Orbaiceta for five cubs of wolves, 2 reales to one from Mezquíriz for a wolf and another 2 reales to another from Orbaiceta for three cubs of wolves.

Visits / Minuet of the March for the Kingdom entrance

A very interesting chapter in daily life was that of the visits of prelates, viceroys, military men and high ranking personalities from the Spanish and French courts. At the beginning of the 17th century, sub-prior Huarte states in these paragraphs that qualified guests and businessmen arrived:

I don't want to say anything about the people of authoritative and qualified lustre who usually go up in good times from both Navarre and from other parts of Spain and France, for devotion or for other reasons, with accompanying troops, to whom a free table is made, and it has not been seen that this is done at the expense of priors who did not..., such people usually go up for the festivities of Our Lady in September which are called the sueltas.... Nor do I want to dwell on the other people who come to Roncesvalles every day on business, such as the landlords, claveros, censeros and other administrators of the estates they have in both Navarre, especially when the general accounts of the rentas and estates and those of the busts of large and small livestock are examined in Roncesvalles, on which occasions so many people tend to come that they tire, worry and spend money.

According to Martín de Azpilicueta, on such occasions the canons would go to the hospital at night with lighted candles, a large building similar to Itzandegia of more than 500 m2 called Caritat. The pilgrims were there, ready to dine, and they greeted them. The canons, together with the illustrious visitors, went up to a platform to pray with the pilgrims for the benefactors, who were expressly named. After the blessing of the table, the prior, sub-prior or person of distinction would come down from the dais to distribute a loaf of bread, after kissing it, while the ministers of the hospital supplied the rest of the food, broths, meat or fish, depending on the day, without lacking the wine. Without doubt, this is a very apt description for a scenographic recreation.

In 1560 the daughter of the kings of France, Isabella of Valois, who was to marry Philip II in Guadalajara at the beginning of February of that year, passed through the collegiate church. Most of the retinue accompanying her with Antonio de Borbón, King consort of the Ultrapuertos of Navarre leave and his brother Cardinal Borbón, after a harrowing journey complicated by snow and snowdrifts, arrived at the collegiate church on 5 January, where the Duke of Infantado and the Archbishop of Burgos were waiting on the Spanish side. The reception was in the aforementioned Caritat building, suitably upholstered and with a richly carpeted dais and red throne. There followed speeches by the Archbishop of Burgos and Don Antonio de Borbón who, after recalling that he was giving the best of France to the Spanish, claimed, as King of Navarre, his rights. The three hundred pilgrims who were present that day then attended the dinner, and the aforementioned Duke of Vendôme and King of Navarre, Don Antonio de Borbón, handed out a coat of arms to each of them. On the visit to the chapel of Sancti Spiritus, the French took the last bones of those who died in the battle of Roncesvalles as relics. When the retinue left the collegiate church, there was snow on the ground and average .

Philip V paid a fleeting visit to the collegiate church on 1 June 1706 on a spring day and stayed, not in the priory house, but in that of Canon Simeón de Guinda y Apeztegui, a native of Esparza de Salazar, who had previously been in Paris for more than two years as procurator of the collegiate church and became friends with the confessor of the Duke of Anjou, later Philip V. The canon was appointed abbot of San Isidoro de León and bishop of Urgel in 1708 and 1714, respectively.

We have more news of the stay in Roncesvalles in 1714 of Isabella of Farnese, the second wife of Philip V, partly due to the account of the Jesuit Manuel Quiñones. The queen arrived on the evening of 8 December and was received by the collegiate chapter with the ringing of bells and many lighted axes. In the church, lavishly decorated with precious hangings and jewellery, she was received under a canopy and a Te Deum and Salve were sung. The following day there was a kissing ceremony and on the 10th she left for Pamplona with two capitulars who joined her entourage. During the stay, 218 capons, 21 rams and 134 pounds of meat were spent, which were bought separately, as well as 300 partridges, 18 turkeys and 97 boxes of preserves of different kinds supplied by the Poor Clares of Santa Engracia in Pamplona. Eighteen jugs of rancid wine were also consumed, and the expense in sea fish amounted to 338 reales. The Queen was presented with two arrobas of dried sweets and a load of rancid wine.

We will close these paragraphs on royal visits with that of the widow of Charles II, Mariana of Neoburg, who on her return from years of exile was received at Roncesvalles on 22 September 1738, before arriving in Pamplona, where she spent Christmas. She was the first royal visit after the dreadful fire at Roncesvalles in 1724.

Death / Bellini's Organ Sonata

Throughout the Middle Ages, average, the belief spread that bodies buried inside churches benefited more from the liturgical services celebrated in them and, therefore, received divine forgiveness sooner; for this reason, the graves close to the altar were of greater value than those further away. Prominent figures left orders in their wills to send their viscera to the shrines of their devotion, such as sample the heart of Charles II in Ujué. As is well known, the monarch, following the tradition of the Capetos, ordered that his body be eviscerated and his entrails deposited in different shrines. His heart arrived at the sanctuary in January 1387. In 1404, Charles III had an oak box made to preserve the viscera.

The sub-prior of the collegiate church noted at the beginning of the 17th century:

I note here an antiquity: that the kings of France and Navarre and many other princes kept a custom and that was that, when they had just died, they embalmed the bodies, especially when they had to be taken far away for burial, and they distributed the heart and entrails, taking them to the churches where the deceased had more devotion..., in which masses and other suffrages were celebrated for the souls on the day they were transferred or deposited.

It includes, among other examples, what happened to Queen Joanna, wife of Charles II, who died in 1374 and was buried in Saint Denis, whose heart went to the Pamplona church and her entrails to Roncesvalles.

The September festival, known as "las sueltas" / Variations on the Magnificat by Miguel Echeveste

Along with the great pilgrimages of the major brotherhoods in June, the great feast of the patron saint of the collegiate church on 8 September was called "las sueltas". In his monograph, Ibarra assumes that etymologically it comes from "absolvere"; therefore, it was the graces and indulgences for visiting the sanctuary on that occasion that determined the name. It was on that day and on the eve of the fairs that numerous alms were collected from devotees and members of the brotherhood who came from Navarre, Aragon and France. In order to maintain order and prevent quarrels, disorder and outrages, a mayor of the Court used to arrive from Pamplona with soldiers from the surrounding valleys. These guards were given a stipend, oil, a bread roll and a pint of wine each on the 7th, and on the 8th, two loaves of bread and three pints of wine. Finally, on the ninth, another two loaves of bread and two pints of wine.

The oft-quoted Juan de Huarte states that on the aforementioned feast of the Nativity of Mary, the sueltas are celebrated "and very loose, since all the sensual senses are loose... So many people attend that, ordinarily, there are more than eight thousand and there are so many burdens and expenses...".

Some sources report the arrival of eight or ten thousand pilgrims, which seems to be a large number. In this regard, it should be borne in mind that the chroniclers indicated these numbers simply to imply that there was a large crowd. In any case, there are specific figures, such as the 1,200 rations given on 8 September 1772 and 1,680 rations on the same day in 1773.

The chapter's conference proceedings records protests from various canons on different dates on the occasion of those festivities. There were years in which on the night of 7-8 September the church, which was usually left open on that occasion, had to be closed. In this regard, it should be remembered that in Pamplona Cathedral, on the day of its patron saint, 15 August, the crowds were such that an armed guard was stationed inside the church to prevent disorder.

In 1768, a large number of the faithful attended, most of them with "devout edification". However, it was noted that for some years there had been intolerable scandals in the opinion of the canons due to the arrival of a certain shopkeeper or merchant from Pamplona, who began to bring different kinds of trinkets and, in imitation of her, her maid and other quincalleros, merchants, silversmiths and shopkeepers of different kinds. All these stalls attracted French and Navarrese young men and women "who spend the nights in the nearby mountains and in places that are very suitable for the dissolutions and offences of God".

Faced with this, the chapter had been requesting financial aid from the mayors and viceroys to put soldiers in the port, but it was not possible to remedy "such a vicious competition". When this was not stopped and wishing that everything would be infused with devotion, without wanting to hinder the bringing in of supplies and food, they asked the courts to prohibit the sale of "marchanterías, alhajitas de plata y otras menudencias, causa de atraer el vicioso y perjudicial concurso" (silver jewelry and other trifles, cause of attracting the vicious and harmful competition).