17 May

visit to the Discalced Carmelites

Ricardo Fernández Gracia

Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

Convent city and convent architecture: the tracists

Spanish baroque architecture

Convent city / also Pamplona

Uniformity in the Teresian Carmelite Order

Rule and Constitutions of the Order (1623). According to the chapter of 1604, it is literally commanded that "our monasteries, our temples, should NOT BE MAGNIFICENT".

File

Founded: August 24, 1587. Its promoters were Mother Catalina de Cristo, prioress of Pamplona, and the Navarrese nobleman Martín Cruzat y Oiz, prior at that time of the convent of Segovia.

Affiliation: Discalced Carmelites of Segovia.

Primitive location: outside the city walls in the neighborhood of La Magdalena. Its church was inaugurated in 1612 and was placed as model in Corella.

Transfers: in 1637 they moved to the city within the city walls, residing while the new convent was being built in some provisional houses. Around 1640 the community settled in what would become the present convent.

Exclaustration: on the occasion of the disentailment of Mendizábal in 1835-1836.

Restoration of convent life: May 23, 1895.

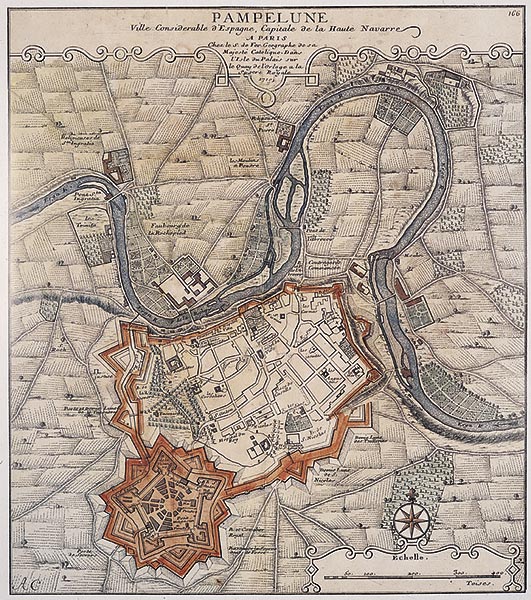

Engraved map of the city of Pamplona, by Nicolas de Fer (1719).

Construction

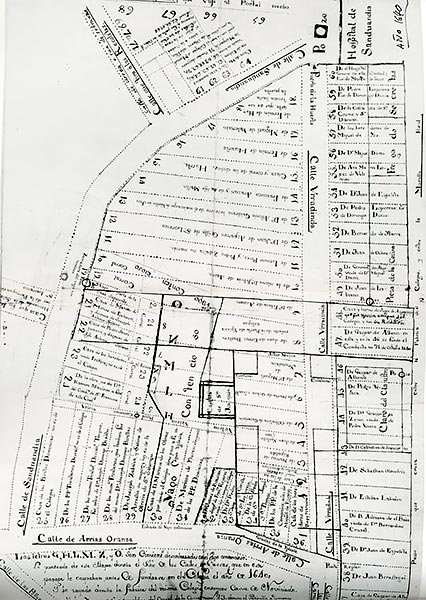

licence to settle in the city in 1637, provisional headquarters. Between 1640 and 1660 the Carmelites bought a total of 71 houses for more than 10,000 ducats. They obtained permission from the City Council in 1647 to occupy Urradinda Street.

The tracist Brother Nicolás arrived from Calahorra in 1637 and in 1639 the prior Friar Alonso de San José (Calahorra, Avila, Corella...).

Other tracists: as far as this convent is concerned, we have located the presence or performance of other Carmelite tracists such as fray Ginés de la Madre de Dios, prior of Pamplona in 1623, who projected the parish church of Santiago de Calahorra; fray Pedro de Santo Tomás, tracista and conventual of Pamplona in 1666; Juan de San José, who in 1673 gave his opinion from Alba de Tormes on the measurements of the façade of the church of Pamplona; Fray Francisco de Jesús y María and Fray Martín de San José, altarpiece designers; and finally Fray José de los Santos who, in the middle of the 18th century, designed the chapel of San Joaquín.

Cloister: 1644, by Juan de Urquía, master stonemason, and José de Lagurrea, master mason. In 1649 walls and in 1730, the Library Services.

Church: from 1661; between 1662-1664, acquisition of plinth stone; masonry between 1664 and 1669.

Inauguration: The temple, dedicated to St. Anne, was inaugurated on her feast day in 1669, with Friar Juan de San Joaquín as prior, and this important event was attended by the Father General of the Order and the Viceroy along with other authorities.

Chapel of San Joaquín remodeled and decorated in 1750 by Fray José de los Santos.

Façade: Contracted in 1667 with Pedro de Azpíroz, putting as model that of the convent of Lazcano. Stone from the Olcoz quarries. Last appraisal by Friar Juan de San José in 1673.

Original plan of the urban sector where the convent was built (1640).

Retablos

Francisco de Jesús María: Two generals of the Order who had professed in this house, Fray Esteban de San José (1664-1670) and Fray Mateo de San Gerardo (1670-1671), who contributed the high sum of 8,000 silver ducats that were used in the façade, the brickwork of the church and the setting of the altarpieces, played a decisive role in its financing with their donations. It is similar to Jesús y María de Valladolid, Peñaranda de Bracamonte and Alba de Tormes. Current owner (1915) Francisco Font. Gilded in 1916.

Collaterals: with changes of dedication and reforms in 1933.

Chapels: The traces for its execution were designed by artisans of the Order, specifically by the master architects Fray Francisco de Jesús y María and Fray Martín de San José, conventual in Pamplona in the last third of the 17th century.

Santa Teresa: registration, 1690. board of trustees The chapel of Santa Teresa was owned by Don Marcos de Echauri, secretary of His Majesty and of the committee of Navarra and benefactor of the convent, since 1689, the year in which he acquired it for 100 silver ducats after obtaining the licence from the General of the Order.

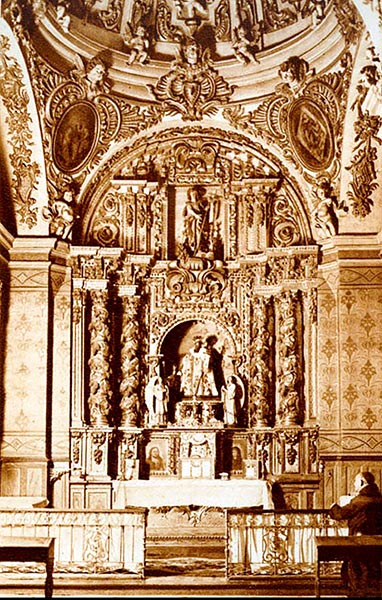

San Joaquín: 1667 by Francisco Gurrea and Sebastián de Sola y Calahorra. Finished by 1669, before the death of Fray Juan de Jesús San Joaquín. Polychromy in 1670 by Pedro de Castillejo y Fuentes, for 600 ducats contributed by Don Juan de Aguirre, from His Majesty's committee , Don Francisco de Espeleta, Knight of the Order of Santiago and Lord of Otazu, Don Martín de Rada, Knight of the same Order, Don Felipe de Errazu, from the Royal committee and Don Sebastián de Esparza, chaplain of the Recoletas.

Church of the Discalced Carmelites of Pamplona, built between 1642 and 1672.

San Joaquín and the origins of his cult in Pamplona

plenary session of the Executive Council In the seventeenth century, a lay Carmelite brother, Brother Juan de Jesús San Joaquín (1590-1669), a native of Añorbe, resided in the capital of Navarre. His life became popular shortly after his death, because it was printed in 1684. From then until a century ago, the seiscentist text has been reprinted several times. Among the numerous events, some of a marvelous nature, very much in tune with the 17th century, his biography narrates everything related to the extension of the cult of St. Joachim, a task that the aforementioned layman took very seriously. As it could not be less, the imposition of the name of Joaquín was popularized and in a special way to children who were born of marriages with great problems to obtain succession.

The author of the book we are quoting, Father Bartolomé de Santa María, writes at length about the hypothetical first case with the aforementioned name, in Navarre, "and probably in all of Spain, where since then the Joaquins multiplied. This was in the year 1636". The protagonists of the event were the marriage formed by Don Juan de Aguirre, oidor of the Royal committee of Navarre, and Doña Dionisia de Álava y Santamaría, his niece, who married after entrusting the matter to Saint Joaquín through her brother. After having several daughters, Don Juan told Brother Juan to "beg the saint, since he had married them, to give them a son. He offered him and a few days later he said to Don Juan: "You already have a son. -What do we already have him? -Don Juan replied, "Dona Dionisia has had signs against it.- You already have him," replied the brother, "from three days ago: be careful and you will find that it is so. The story is very long and ends with the birth of Don Joaquín de Aguirre Álava y Santamaría. The father of the child wanted to know how the layman had such success and conviction, to which he answered that "it was the saint who had assured him of the conception, and when he went to see them, he saw Doña Dionisia leaving the house for mass, and in front of her the child that was to be born".

This was not the most famous case, but another Joaquín, son of the viceroys of Navarre, from Oropesa, who was given the name of Manuel Joaquín, in Pamplona on Epiphany in 1644, and whose birthday was perpetuated by Antonio de Solís in a comedy entitled Eurídice and Orfeo and popularized by José María Iribarren in his book De Pascuas a Ramos (From Easter to Palm Sunday).

The Jesuit Juan Bautista León, in two volumes dedicated to the cult of St. Joaquín, also tells us of other events that occurred with the lay brother of Añorbe and of the extension of the cult of the saint and the dedication of temples and altarpieces from his chapel in the Discalced Carmelites of Pamplona to Tarazona, Toro, Valencia, Jumilla, Monovar, Villena, Avila, Bilbao, Játiva and Sicily. In Navarra, some of the hermitages dedicated to St. Joaquín have their origin precisely in the figure of Brother Juan.

Old postcard of the chapel of San Joaquin.

A series of six Josephine canvases in the Carmelite monastery of Pamplona

Patron: José Francisco Bigüézal, bishop of Ciudad Rodrigo between 1756 and 1762. The realization must have been delayed until 1765, judging by some lawsuit that the friars maintained in relation to the patron of one of the chapels of the church. Its author was Pedro de Rada, a painter established in Pamplona in the second third of the eighteenth century and with extensive work, both in the sacristy of the cathedral and in various commissions from the institutions of the Kingdom.

Five passages from the New Testament were included in the cycle: the Adoration of the Shepherds (Lk 2:8-20), the Circumcision of the Child Jesus (Lk 2:21), the presentation of the Child Jesus in the Temple (Lk 2:22-40), the Flight into Egypt (Mt 2:13-15, 19-23) and the Child Jesus lost and found in the Temple (Lk 2:41-52). To these scenes was added a sixth, with the topic of the death of St. Joseph, narrated in the Apocrypha and other texts published from the sixteenth century onwards.

The painter, like many others, based his compositions on engraved prints. However, despite what we might think, he did not use a specific series of prints, but rather each of the passages was copied from different intaglio prints that, most probably, the Carmelites themselves gave to Pedro de Rada.

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

AZANZA LÓPEZ, J. J., Arquitectura religiosa del Barroco en Navarra, Pamplona, Government of Navarra, 1998.

ECHEVERRÍA GOÑI, P. and FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., "El convento e iglesia de los Carmelitas Descalzos de Pamplona. Architecture", Príncipe de Viana (1981), pp. 787-818 and "The convent and church of the Discalced Carmelites of Pamplona. Artistic decoration", Príncipe de Viana (1981), pp. 819-891.

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., El retablo barroco en Navarra, Pamplona, Government of Navarre, 2003.