26 September

The queen also dies: hieroglyphs at core topic female

in the cathedral of Pamplona

José Javier Azanza López

Chair de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro

The funeral honors for royal personages were celebrated sumptuously in Pamplona and its cathedral, being the capital of the kingdom and episcopal see, an act that preceded those that days later were organized in the rest of the cities of the Navarrese territory.

The Pamplona church hosted, in the XVII and XVIII centuries, the funeral honors of a group of queen consorts or widows of the Hispanic monarchy. They are Isabel de Borbón (wife of Felipe IV) in 1644; María Luisa de Orleans (wife of Carlos II) in 1689; Mariana de Austria (widow of Felipe IV) in 1696; María Luisa Gabriela de Saboya (wife of Felipe V) in 1714; Louise Elizabeth of Orleans (widow of Louis I) in 1742; Mariana of Neoburg (widow of Charles II) in 1740; Maria Barbara de Braganza (wife of Ferdinand VI) in 1758; Maria Amalia of Saxony (wife of Charles III) in 1760; and Isabella of Farnese (widow of Philip V) in 1766.

According to the ceremonial of royal funerals in Pamplona, the arrival of the official letter signed by the king announcing the death of the royalty (wife, mother) immediately triggered a complex mechanism aimed at carrying out the function of royal funerals which, in the case of Pamplona, had a double character, was of a double nature, since from the middle of the 16th century and due to a question of preeminence in the protocol, a royal provision of Felipe II allowed the Regiment of the city to organize its own funeral honors, apart and on a different day from those of the viceroy and committee Real. Both ceremonies, held consecutively, included vespers, vigil and solemn mass.

The magnificence and apparatus that the funeral ceremony required implied the effort of different trades, from those responsible for its organization to the tailors, upholsterers, wax workers, carpenters, painters, intellectuals, orators and, finally, engravers and printers who recorded the mournful event in the list of funerals and the funeral sermon. The main interest of all of them was directed to the great ceremony in the cathedral, whose space was insufficient to comfortably accommodate the faithful and authorities. The most outstanding piece of the "theater of death" is a gigantic architecture of varied typology: the tumulus or catafalque, which in the cathedral stage becomes the point of reference letter around which the drama of the funeral turns, metaphor by which the deceased queen is made present to her subjects by means of the symbols that represent her.

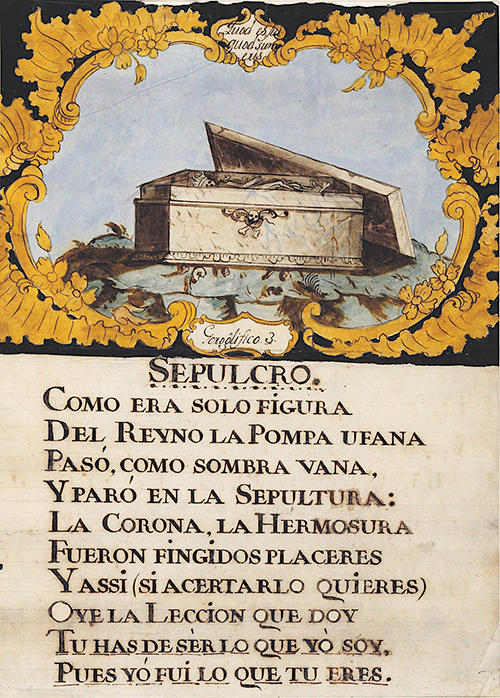

The catafalque was erected in the middle of the Wayside Cross, in the free space between the grilles of the main chapel and the choir that then occupied part of the central nave, being necessary to dismantle the grille of the via sacra. It covered most of the Wayside Cross both in plan and in elevation. Parallel to the work of the carpenters, who assembled a complex system of scaffolding, the painters proceeded to give a bath of black to the capelardente, at the same time that they worked on the paintings of shields, royal crowns and skulls destined for the funeral machine. The upholsterers replaced the black velvet cloths that were in poor condition, and the wax workers were in charge of providing the multitude of candles and candles of the tumulus, whose tremulous lights recreated the dramatic atmosphere required by the funerary architecture. A figurative coffin, covered by rich brocade cloths, was installed in a preferential place, although in Pamplona's funerals, in the second half of the 18th century, the placement of a large canvas with a skeleton was imposed, a reflection of the equalizing power of death that does not spare even kings and queens.

In the seventeenth century, one of the most important catafalques was erected in 1696 for the funeral of Mariana of Austria, whose composition associated with Italian mannerism is due to its author, the military engineer Hercules Torelli. Simpler is the tumulus erected in most of the funerals of the eighteenth century, configured as a huge machine of subject turriform formed by a base on which rise several decreasing bodies, on top of which was the royal tomb. To the tumulus was attached a portable pulpit from which the sacred orator pronounced the funeral sermon.

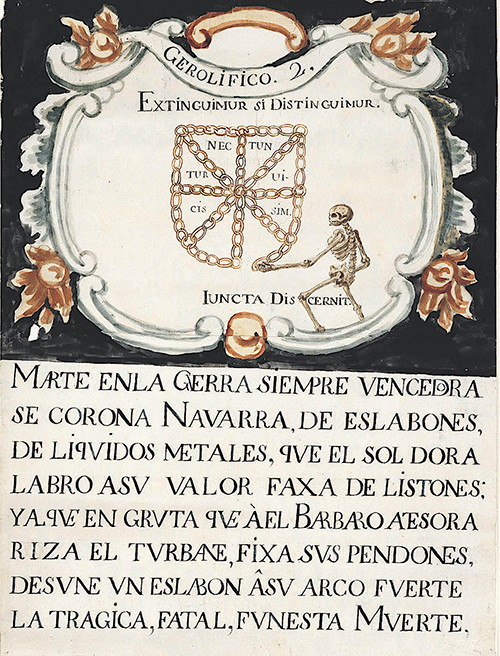

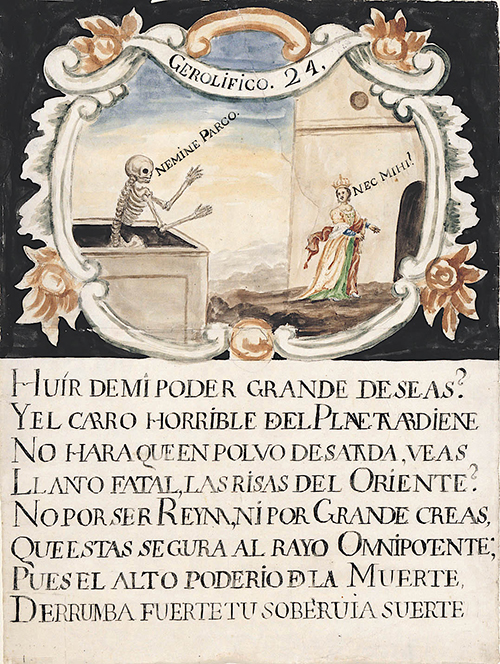

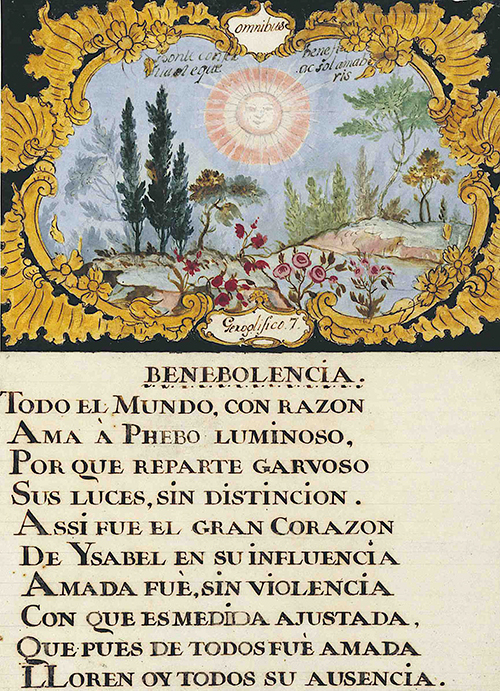

An essential element of the tumuli were the emblems and hieroglyphs, whose execution involved scholars and painters. The former were generally notable jurists and theologians who were inspired by various sources such as the Holy Scriptures, mythology, history and Greek and Latin writings, as well as by the books of companies or emblems, whose knowledge in Pamplona's intellectual circles we know from the inventories of libraries of the time. And it is that in the composition of the tumulus the intervention of a mentor instructed in the symbols and allegories, manager of the "ideological coating" of the machine was essential. For their part, the painters were in charge of materially translating the ideas of the former.

Hieroglyphic obsequies Bárbara de Braganza (1758).

file Municipal of Pamplona.

The hieroglyphs were, therefore, visual riddles that through the combination of image and text made the funerary monument "speak" of the glory of the deceased queen. Exceptionally, the series of hieroglyphs arranged in the first body of the tumulus that the Regiment of the city erected in the 18th century for the funeral riddles of the queens Bárbara de Braganza (1758) and Isabel de Farnesio (1766), a faithful and direct testimony of the Baroque festivities in Navarre, have been preserved in the Municipal file of Pamplona. Made on vat paper in the form of large cards and with an average size of 60 x cm, they are one of the few cases in which the original emblems have reached our days, given that most of the time we have knowledge of them through the engravings that illustrate the reports of funerals.

Hieroglyphic obsequies Bárbara de Braganza (1758).

file Municipal of Pamplona.

The Pamplona hieroglyphs for the death of the queens conform to the canonical composition of the triplex alciatino emblem formed by motto or mote in Latin language , body or pictura, and epigram in the form of Castilian poetry, and insist on a message linked in a coherent speech , which also shows an obvious parallelism with the funeral oration preached by the sacred orator from the portable pulpit of the burial mound. Moreover, there is often a feedback between the contents of the sermon and the hieroglyphs, in such a way that the former finds its pictorial embodiment in the compositions that decorate the tumulus, while the latter are explained in the rhetorical resource of the preacher, who acts almost as if it were a declaratio. The idea of "preaching to the eyes", which, as Giuseppina Ledda analyzes, promotes the presence of absence, thus acquires plenary session of the Executive Council meaning, thanks to the fact that the image (in this case real as it is embodied in the painting of the hieroglyphs) acts as an echo and sounding board for the word, and vice versa.

Hieroglyphic funeral of Isabel de Farnesio (1766).

file Municipal of Pamplona

Both the iconographic program of the tumulus and the funeral oration of the preacher unfailingly begin with the deep sorrow that overwhelms the hearts of the Navarrese subjects when they learn the fatal news of the queen's death. For this purpose, either universal symbols or symbols related to the city and the kingdom are used, easily identifiable by those attending the ceremony: the lion -king of the animals and protagonist of the coat of arms of Pamplona-, the Five Wounds or the chains of the coat of arms of Navarre.

Hieroglyphic funeral of Isabel de Farnesio (1766).

file Municipal of Pamplona.

Once the pain has been recorded, a reflection on the event that provokes it is unavoidable: time and all-consuming death cannot be absent from the funeral ceremonies of the Modern Age, given the transcendental sense that permeates Christian thought. Consequently, tombs, skeletons and skulls are the protagonists of a good part of the Pamplona hieroglyphs for our queens, accompanied by other metaphors of the inexorable passage of time such as the hourglass, the flow of water that falls, the candle that is consumed or the butterfly that burns in its flame. The death of the queen is also expressed through celestial images such as the setting of the moon or the vision of a comet, since the entire cosmos serves to reflect the vicissitudes of royalty.

But in a society like the baroque one that believes in immortality, death does not have the last word, nor can it celebrate its triumph if there is hope in an afterlife. For this reason, neither the sermon nor the iconographic program of the tumulus represent the triumph of death, but the triumph over death that supposes the passage from the earthly sphere to the celestial sphere. It will be a virtuous life that will guarantee eternity to the deceased queen and will turn her into model of conduct for her vassals. And in this way we find allusions to the charity and generosity, fortitude, prudence, temperance and fidelity with which our queens conducted themselves in life. With this baggage, the queen reaches the port of glory and enjoys the reward of eternal life.

Consequently, the initial sorrow of the iconographic program of the hieroglyphs and the funeral prayer is transformed into final rejoicing, thanks to the image of the virtuous queen who triumphs over the destructive power of death and is proposal as model of conduct to imitate to achieve eternal life. This was, ultimately written request, the true essence and meaning of the royal funeral ceremony for our queens.

To learn more:

AZANZA LÓPEZ, J. J., "Túmulos y jeroglíficos en Pamplona por la muerte de Isabel de Farnesio", file Español de Arte, n.º 289, 2000, pp. 45-61.

AZANZA LÓPEZ, J. J. and MOLINS MUGUETA, J. L., Exequias reales del Regimiento pamplonés en la Edad Moderna. Ceremonial funeral, ephemeral art and emblematic, Pamplona, Pamplona City Council, 2005.

AZANZA LÓPEZ, J. J., "Jeroglíficos en las exequias pamplonesas de una reina portuguesa: Bárbara de Braganza (1758)", in Paisajes emblemáticos: la construcción de la imagen simbólica en Europa y América (eds. C. Chaparro, J. J. García Arranz, J. Roso y J. Ureña), Tomo 1, Mérida, Editora Regional de Extremadura, 2008, pp. 339-360.

AZANZA LÓPEZ, J. J., "Oración fúnebre, emblemática y jeroglíficos en las exequias reales: palabra e imagen al servicio de la exaltación regia", in Emblemática trascendente. Hermeneutics of the image, iconology of the text (eds. R. Zafra and J. J. Azanza), Pamplona, Spanish Society of Emblematics and University of Navarra, 2011, pp. 175-194.

AZANZA LÓPEZ, J. J., "Los grandes proyectos de arquitectura efímera", in El arte del Barroco en Navarra ( coord. Ricardo Fernández Gracia), Pamplona, Gobierno de Navarra, 2014, pp. 155-163.