September 28

Women in the printing presses of Navarre (1490-1841)

Javier Itúrbide

Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

It exposes the status of women linked to the printing business and bookshop from 1490, when the first printing press was installed in the kingdom of Navarre, until 1841, the year in which, as a result of the Ley Paccionada, the committee Real de Navarra, which since the sixteenth century had exercised the exclusive School to control the publishing of books in the kingdom of Navarre, was extinguished.

It is clearly difficult to trace the traces of women related to the "mechanical art" of printing, since it is the male who holds the ownership, either as owner or as manager. In spite of this, the printing footers and the notarial and ecclesiastical documentation provide a glimpse into their life staff and work.

From agreement with the practices of the time, women do not have access to the remunerated "offices" and providers of work that sustain the institutions and that, in the case of Navarre, refer fundamentally to the "Printer of the Kingdom", "Printer of the Royal Courts" and "Printer of the Regiment of Pamplona". Their condition as women prevents them from continuing with these positions when they are widowed, although they will receive for life half of the salary that their husband received.

In most cases, the printing house guide is a family business, run by the father, in which the children participate and in which the wife plays a role that is as anonymous as it is essential. She guarantees the daily life of her family and, in addition, that of the journeymen and apprentices who work in the workshop, to whom guests are often added. Without her it would be very difficult for the workshop to function normally and bookshop; test of this is that during the three hundred years studied there is no record of the existence of a bachelor owner of a printing press. Men marry when they have their own business, when their status is stable. If they are widowed, they do it again in a hurry, in many occasions with a young woman, widowed and with children, who has a considerable patrimony, which can be destined to the expansion of the family business.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, when there was no printing tradition in Navarre, the professionals came from Flanders and France and, when they were successful, they formed a family, taking as their wife a woman from their environment, that is to say, a Navarrese woman. This circumstance will give rise to the creation of Navarrese lineages of printers in which the woman, widow or heiress daughter, will often serve as a link that will guarantee their continuity. An early example is Arnao Guillén de Brocar, the first printer, who settled in Pamplona around 1490 and married María de Zozaya.

It is taken for granted that a woman cannot appear at the head of an artisan activity, that when her husband dies she inherits the property, but she cannot state that she is the owner. Thus, as long as she does not marry, she will appear on the covers of her books as "widow of...", never with her name and surname. This would be the case of María Ramona Echeverz, widow since 1782 of José Miguel Ezquerro, who did not remarry and who, during the 22 years she was in charge of her business, always read on her covers: "In the printing house of the widow of Ezquerro".

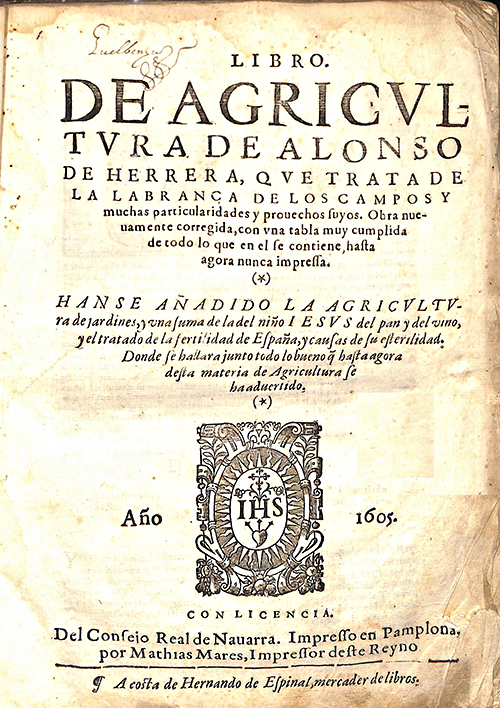

In the event that the widow is of age to remarry, she must do so with haste to ensure the normal operation of the business she has just inherited. After her marriage, the works will be signed by her husband, although making it clear that he is not the owner. For this reason, the title page does not read "in the printing house of..." but "printed by...". An example is the case of Graciosa de Oroz, widow of Pedro Porralis since 1596, who remarried a few months after her husband's death, and the title pages bear her husband's name: "Printed by Matías Mares".

By Mathias Mares

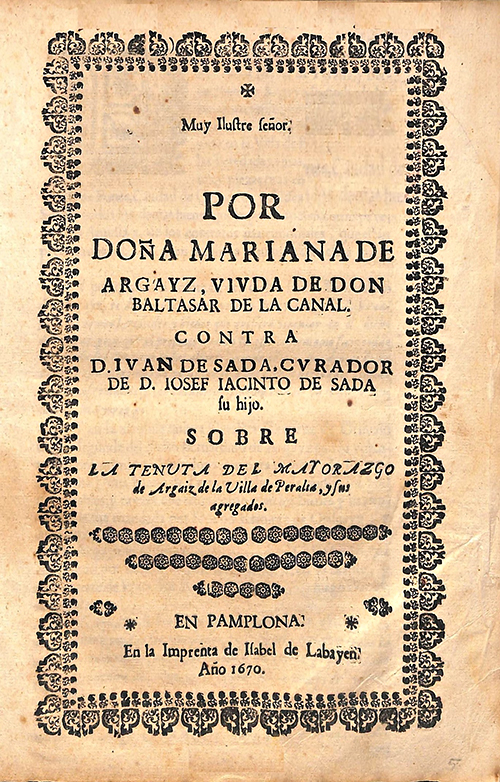

In the four centuries studied, there is only one known case in which a woman appears as the owner of a printing press. It is obviously exceptional and was due to a family conflict: Isabel Labayen had inherited her father's business and was married for the second time. She had a dispute over the ownership of the workshop with her heir, the son of her first marriage, and her second husband had robbed and abandoned her. She was alone, she had no one to entrust the business to and, for this reason, between 1669 and 1670, the little she printed bore her name on the title page with the precision of her ownership: "In the printing house of Isabel de Labayen". This anomalous status lasted two years, the time it took to sign the judicial sentence that recognized the ownership of the mother and assigned the son the function of a mere employee.

At the printing house of Isabel de Labayen

It had to be in the Age of Enlightenment when the marginalization of women was rectified as far as the ownership of businesses related to a "guild, art and official document" was concerned. The Royal Order of 1790 established that in order to continue running her business, she did not have to marry a worker from official document and, henceforth, it would be sufficient for her to simply hire him. At last the widow's property was freed from the duty of contracting a compulsory marriage. As far as legality is concerned, it is well known that the application of the law is hampered by social and cultural prejudices.