June 28

Intangible heritage: the festive calendar of Pamplona Cathedral

Alejandro Aranda Ruiz

Technician for movable property of the Archbishopric of Pamplona and Tudela

Introduction. The tangible and intangible heritage: two heritages that feed back on each other.

It is very likely that you are wondering about the reasons for the inclusion of a lecture on intangible heritage in a a course focusing on a single topic of movable art in the cathedral. In an attempt to justify this, let me start with the UNESCO definition of intangible heritage in its 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage: "Intangible cultural heritage means the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills - together with the instruments, objects, artifacts and cultural spaces associated therewith - that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage".

As we can see, the answer to our question is found in the same UNESCO definition that speaks of "instruments, objects, artifacts and cultural spaces" that are inherent to intangible heritage. And the fact is that intangible heritage is not only composed of intangible elements that give it the name of intangible and that only exist while they are being performed (a dance or a piece of music), but also of material elements that support the intangible and that serve to represent the meanings and messages that we want to convey with this intangible heritage. Sometimes, in fact, the tangible heritage is essential for the existence of the intangible. A good example of this is the Catholic mass, whose existence depends (among many other things, of course) on something as simple and material as wheat bread and vine wine.

On the other hand, the definition also includes the cultural spaces, that is to say, the framework in which the intangible heritage is developed and that, like the material, is essential to understand the reason for the intangible heritage. Let us think of the procession of San Fermín that every year crosses the streets of the Old Helmet of Pamplona. Now let's think about moving that same procession, with all its human elements and Materials (participants, costumes, music, dances), to New York's Fifth Avenue. Would it be the same? Evidently not. The routes and distances, the rhythms (essential parts of the rite, forged throughout the centuries, fruit of lawsuits and agreements) of the procession would be altered.

Therefore, we could say that intangible heritage forms a tandem with tangible heritage. The former gives the latter meaning and significance, and the latter gives the former a body and a space. Both heritages feed back on each other and combined give rise to what we call Cultural Heritage with capital letters.

2. The sources of the cathedral liturgy

Until the Council of Trent (1545-1563), the dioceses had a certain independence with regard to liturgy. Bishops and councils legislated quite freely on these matters, hence part of the liturgy varied from one diocese or cathedral to another. The best example of this is the coexistence with the Roman rite of different rites in the celebration of the Mass and in official document divino: the Sarum rite in England, the Gallican rite in France, the Ambrosian rite in the north of Italy or the Mozarabic rite in the Iberian Peninsula. In this diocese, the Mozarabic liturgy was in force until the 11th century, when the Roman rite was imposed, not without resistance from the clergy. Despite the generalization of the Roman rite in Western Christianity from the 11th century onwards, the churches continued to maintain their traditions until the arrival of the Council of Trent.

In the case of Pamplona, its oldest traditions are collected in part in the breviaries of the cathedral of 1332, 1349-1354, one from after 1388 and another from the middle of the 15th century, and in the choir rules written in the 15th century and which collect traditions from the 14th century. In addition, there are sheets of single masses and the antiphons of San Fermin, the Manuale secundum consuetudine ecclesiae Pampilonensis of 1489 and the Missale Mixtum Pampilonense, edited around 1500, and the Missale Pampilonense of 1557.

The arrival of the Council of Trent meant in Pamplona the withdrawal of the old liturgical books: in 1576 the Roman Missal of 1570 was promulgated, around 1586 the breviaries were abandoned and in 1598 the old choir rules were replaced by new ones at the request of Bishop Antonio Zapata, who was the great promoter of the Tridentine liturgy in the cathedral. In spite of this, the application of the Council of Trent did not put an end to the infinity of traditions that were inserted without major problems in the new liturgy. These traditions were passed down from generation to generation. The Cabildo watched over the conservation and purity of its traditions, making decisions in this respect. In the 18th century, the work of the prior Fermín de Lubián, one of the most brilliant heads of the Navarre of his time, who compiled all the ceremonial in force in his time and studied its history, reflecting it in the cathedral chronicle entitled Notum, which begins with a "Relación de todas las festividades ordinarias de entre año" (Report of all the ordinary festivities of the year), was outstanding.

At the end of the 18th century, and especially during the 19th century, there was a tendency to purify the cathedral ceremonial and liturgy in a desire to do away with elements that were considered abusive or contrary to the official liturgy. There is a desire of romanization, of standardization, of a more severe and severe liturgy. In this sense, the work of the cathedral masters of ceremonies, such as Bernardo Astráin, Gregorio Lorea, Bartolomé de Oyeregui, his nephew Pedro María Ilundáin, Desiderio Azcoita or José Magaña, who wrote reports and memorials to the Chapter exposing the failures and abuses that should be improved, will stand out in this period. There were also attempts to write ceremonials that compiled the liturgy of the cathedral. In 1820, the Chapter commissioned Bernardo Astráin to compile the material to transcribe a ceremonial that was not done. Around 1877, Desiderio Azcoita wrote a ceremonial in which all the customs that had survived up to that moment were collected: the theoretical and practicalguide of the ceremonies of the Holy Church Cathedral of Pamplona in the main festivities.

In 1931, the Chapter approved a Choir Regulation of the Holy Church Cathedral of Pamplona in which, in spite of the passing of the years, numerous traditions already mentioned in the guide of Azcoita or in the Notum of Lubián. It was from the middle of the 20th century when the atmosphere created around the Second Vatican Council, the liturgical reform, the vocational crisis and other factors brought about the more or less abrupt end of the secular traditions that had survived until then, although some, although modified, have come down to us as a pale reflection of what was the liturgical and ceremonial life of the cathedral.

In summary, the sources of the cathedral liturgy were: the local tradition, created by decision of the bishops or the Chapter by means of decrees, diocesan synods or chapter agreements, transmitted from generation to generation and preserved thanks to the zeal of the Chapter and of the masters of ceremonies who took notes and elaborated ceremonials. To this were added the liturgical books of the universal Church, especially since the Council of Trent, such as the Roman Missal, the Roman Pontifical, the Ceremonial of Bishops and the decrees of the Sacred Congregation of Rites, founded by Sixtus V in 1578 and with School to legislate in subject liturgy for the entire Latin Church.

3. The cathedral's intangible heritage and one of its most characteristic elements: the processions.

The ceremonies that took place in the cathedral until the middle of the 20th century were basically reduced to the celebration of mass, the singing or recitation of the divine official document in the choir and the celebration of processions. The solemnity with which these ceremonies and rites were performed varied according to the subject festivity being celebrated or the liturgical season in which it took place. The year was organized around the liturgical cycles of Advent-Christmas and Lent-Holy Week-Easter. To these two times were added festivities and commemorations of Christ, the Virgin and the saints. The category of these feasts and, consequently, the liturgical solemnity with which they were celebrated varied from one to another. Already in the breviary of 1332 we find a hierarchy of these feasts, dividing them into most excellent and principal. The taxonomy used by the choir rules of 1598 organized the feasts according to the issue of captains or canons that with cape and scepter had to be present in some ceremonies: feasts of six capes, of four and of two.

For reasons of time, of the three types of ceremonies that were celebrated in the cathedral (mass, official document divino and processions), we will only deal briefly with the processions. These can be divided into two categories: those in which the procession was reduced to the cathedral and its cloister (cloister processions) and those that went outside the walls of the cathedral and went through the main streets of the city (general processions).

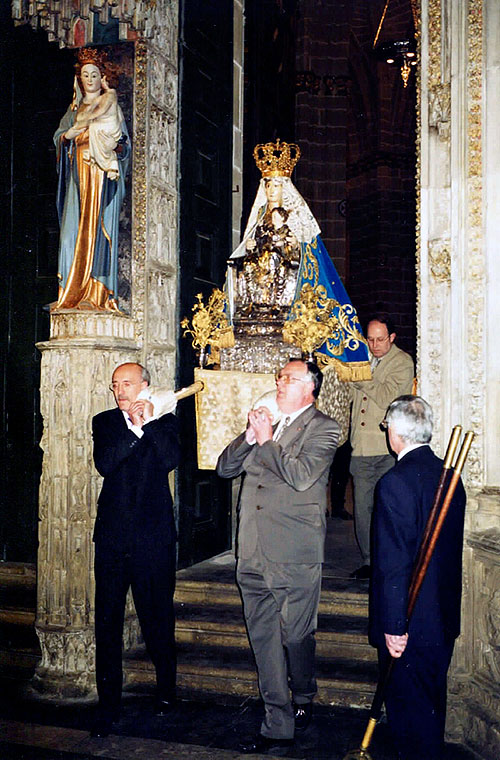

Virgen del Sagrario in the procession of the meeting, years 2000.

Private collection.

Regarding the cloister processions, these have been documented since the average Age and were celebrated on a regular basis every day. As Santiaga Hidalgo points out, some of them were simple displacements between two places where different rituals were celebrated and others went through the spaces of the cathedral and the cloister, being able to make stops or stations in certain places. In these processions, the Chapter paraded in rows, preceded by the macero and the perrero or silenciero, both with their rods or poles and processional cross between candlesticks. On the occasion of certain solemnities, in the 16th century, two, four or six canons wore silk cloaks, and since the Age of average the image of the Virgin of the Tabernacle or different relics could be included in the procession. These processions were accompanied by certain chants and prayers compiled in the processional books of the cathedral that are preserved in the file of music. These chants generally consisted of the singing of an antiphon, a short responsory and a prayer by the preste who officiated in the procession. It was usual to sing as many antiphons, responsories and prayers as there were stops or stations.

The cloister processions that we could call 'prototypical' were those that were celebrated on Sundays and first days class, generally after terce. To these were added others that were particular to certain festivities and that were characterized by having a specific ceremonial, such as the procession of Epiphany, the processions of the Lignum Crucis on Wednesdays and Fridays of Lent and the days of the Invention (May 3), Triumph (July 16) and Exaltation (July 16), Triumph (July 16) and Exaltation of the Holy Cross (September 14), the processions of Vexilla on the Sundays of Passion and Palm and the Saturdays immediately following them and the processions with the Virgin of the Tabernacle that were celebrated on Easter Sunday and on August 15 and 22.

The extramural processions were called general because they were attended by the parishes of the city and sometimes by the convents and brotherhoods, the City Council and the Royal Courts with the viceroy. These processions were presided over by the Cathedral Chapter and this fact, and the fact that they were general, meant that the processions went through the different parish jurisdictions of the city, something that a single parish could not do on its own. Aspects such as beginning and ending at the cathedral, the accompaniment of guilds, convents, parishes and the City Council to the Cabildo, places of celebration of the offices and other ceremonial details were fixed for many of these processions in a concord established in 1626. The general processions are divided into those of the universal Church and those particular to Pamplona.

Within the first group were the processions of major and minor litanies and the Corpus Christi procession. The procession of major litanies took place on St. Mark's Day and those of minor litanies on the three days prior to Ascension Thursday. On the day of San Marcos the procession went to the church of San Lorenzo and on the days of major litanies, until approximately 1590, on Mondays and Tuesdays it went to Burlada and Ansoáin and on Wednesdays to San Saturnino. From at least 1598, on Mondays it went to San Nicolás, on Tuesdays to San Lorenzo and on Wednesdays to San Saturnino. These processions were attended with the Cabildo, at least since the sixteenth century, the City Council of the city. In addition to these processions was that of Corpus Christi, the most important procession of Pamplona, celebrated at least since 1320 and that in the Modern Age acquired a great impulse thanks to the Council of Trent and the Catholic Reformation. The procession had a general character, it left and returned from the cathedral and was attended by the parishes, convents, guilds, City Hall, Royal Courts and viceroy.

Reliquary of San Fermin, cross of relics and reliquary of St. Paul, used together with the reliquary of St. Stephen in the first cloister processions class. Photo: Alejandro Aranda.

As we were saying, to the general processions commanded by the church were added the particular ones of Pamplona, fruit in many occasions of a vow made by the City Council of the capital to some saint in gratitude for the end of some public calamity that affected the people or the fields and livestock on which the sustenance of the population depended. These processions, regulated final by the concord of 1626, had the characteristic of leaving and returning from the cathedral. In some of them (San Martín, San Nicasio, San Sebastián, San Gregorio Ostiense and Santos Abdón and Senén), the mass that followed the procession was celebrated in the cathedral. In others, however, the mass was celebrated in another temple, such as in the church of San Saturnino (San Saturnino), in the church of San Lorenzo (San Fermín) or in the Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Love of the saint to whom the festivity was dedicated (San Jorge and San Roque).

These general processions, which were maintained until the 19th century, were not the only ones, since in the Age average there were others that with the passage of time either disappeared or became cloistered, such as that of the Lignum Crucis on September 14. Thus, in St. Peter's there was a procession through the city with the Virgin and the ark of relics or on the Sunday after the octave of St. Peter and St. Paul there was a procession with the relic of the crown of thorns.