August 27th

Historic-artistic heritage, a condenser of values and identities

Ricardo Fernández Gracia

Fray Diego de Estella Cultural Center, Estella, Spain

The possibilities for learning and teaching together with cultural heritage are immense: the recreation of everyday life in a monastery, in an urban center, in a palace or linked to objects of everyday life, or showing the sponsorship of the privileged elites in a cathedral, the arrival of formal influences through routes, roads or personal interventions, etc... etc. As a common denominator, it is always desirable to insist on the global vision of cultural heritage for its condensing character, since, in its day, when it was conceived, literature, music, liturgy, protocol, architecture and figurative and sumptuary arts coexisted in a harmonious and integrating way.

Heritage should be considered from three main points of view. Firstly, it must be considered as a support for the collective conscience (tool essential for the historical knowledge ); secondly, as a fundamental socio-economicresource essential for the sustainable development of contemporary societies. Thirdly, it must be examined as source of inspiration and creativity for present and future generations.

An advanced, cultured society with high levels of wellbeing should not allow its cultural heritage to be absent from its daily life. Progress should also be measured by the cultural level achieved by it. It is this vision that has generated in highly developed countries a great social demand for the use and enjoyment of cultural goods. This fact has become a demand on institutions, which has translated into the right of citizens to culture, as recognized in various constitutional texts. source Among the numerous texts emanating from high institutions, we will highlight one of the 1985 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Architectural Heritage of Europe, which calls for "raising public awareness of the value of architectural heritage not only as an element of cultural identity, but also as a source of inspiration and creativity for present and future generations".

The subtitle of this day's intervention in Estella is the following: Contemplating, thinking, reasoning and making history with cultural assets in Estella. Looking, seeing and reading through the cultural heritage can be a profitable exercise when it comes to making readings in core topic cultural of numerous sets of the past. We know texts by Lope de Vega or fray Hortensio Paravicino and other writers where the difference between the act of "looking" and "seeing" is pointed out, attributing to the mass of the population the inability to pass from one stage to the other by understanding the perception of the works as a true intellectual act that demanded the capacity of judgment and discernment, which was forbidden to most of the public. Regarding "reading", Lope de Vega, when dealing with a biblical episode, affirmed: "In an image I read this story", and Father Sigüenza, when referring to a painting by Bosch, asserted: "I confess that I read more in this panel... than in other books in many days". The challenge for the scholar and the citizen of today consists in making plausible analyses and readings of images produced in a context so different from today's and with codes so far removed from our time.

Five points of view

If we reason with the object or monument in front of us from five parameters, we can reach its understanding and contextualization. First, they must be analyzed as history: with their space-time coordinates, their commissioners and their makers (their whys and wherefores). Secondly, to examine them in terms of their technique and material (with what and in what way?). Thirdly, to delve into their aesthetics: creative and formal analysis (how?). Fourthly, to consider them as bearers of meanings based on what they represent in their historical and cultural context (what). Finally, to inquire into the use and function for which they were conceived (what for).

By considering them as history, they will be seen as a faithful expression of it. A time and a space, promoters and executors. Artists and/or craftsmen served the kings, civil and religious institutions, nobles and bourgeois in the city of Estella, making all subject of works and for different purposes. To exemplify this section, comments were made on important works. As a royal donation, the ivory image of the Virgin and Child (1310-1330), which was donated to the Poor Clares by Queen Blanca a century after it was made, and was sold in 1901, was presented as a royal donation. It is currently exhibited in the British Museum. With two altarpieces of painting from the beginning of the 15th century, the international Gothic style was inaugurated in Navarre. Their promoter was Martín Pérez de Eulate (better known as Martín Périz de Estella) for his family chapel in the church of San Miguel de Estella. One -the one dedicated to Saint Helen- remains in situ, while the other, dedicated to Saint Nicasio and Saint Sebastian, is exhibited in the National Archaeological Museum.

Virgin and Child, c. 1310-1330, from the Poor Clares of Estella. Photograph of 1901, at the time of disposal.

The Eguía family and their projects served to show the relationship between the aesthetics of humanism and the new Renaissance style, in some cases coexisting with the late Gothic. The patronage of a bishop was illustrated by the example of Don Prudencio de Sandoval, Benedictine, historian and prelate of Pamplona between 1612 and 1620, who rebuilt the monastery and church of the Benedictines at his own expense.

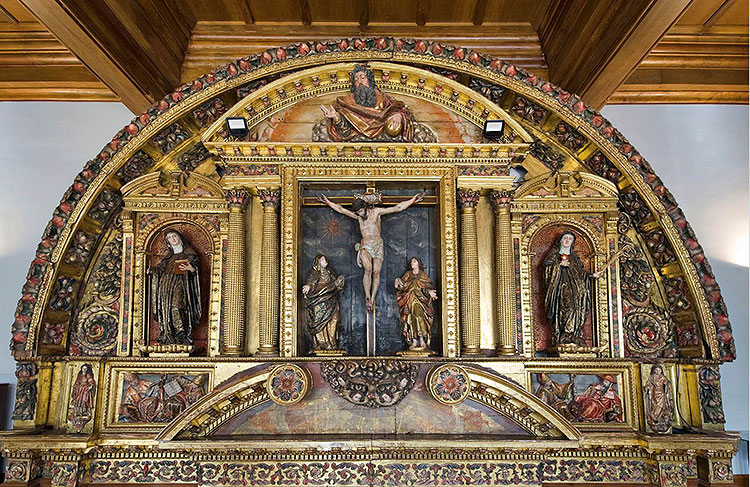

Attic of the main altarpiece of the Benedictine Sisters, today in Leire, work of Juan III Imberto, 1649. Miguel de Brevilla was in charge of its polychromy between 1680 and 1681, despite the attempt to award it to the painter Francisco de Arteta.

The parishes also stood out, obviously, as generators of patrimony of all subject, not only in their buildings, but also in their furnishings. As an example, we use the chapel of the patron saint Saint Andrew in the parish of San Pedro de la Rúa, where nothing was spared, at the end of the 17th century, to create a space where plastic art, color and images took center stage.

The City Council, as an institution, also exercised its patronage and, above all, commissioned royal portraits of the highest quality, generally from the Madrid court, which is where the best art was consumed. Authors such as Miguel Jacinto Meléndez, Antonio Martínez de Espinosa or Pedro Antonio de Rada are among the authors of the oil paintings.

Carlos IV of the Town Hall of Estella by Antonio Martínez de Espinosa, 1789.

It follows models of Francisco Folh de Cardona, painter of Carlos IV's Chamber, and Ginés Andrés de Aguirre, director of Painting of San Fernando and even of the first Goya.

Some wealthy individuals, nobles as well as bourgeois and Indians, could not be absent. The foundress of the Conceptionists, Doña Paula Aguirre, or Don Miguel Francisco Gambarte, resident in Mexico, were generous to the Poor Clares, where the latter had a sister.

Religious communities and confraternities completed the explanation of the promotion of the arts, with such outstanding examples as the Aragonese ternos of Benedictine and Poor Clares or the confraternities of doctors or shoemakers.

The second point of view of analysis of the historical-artistic goods focuses on considering some techniques such as embroidery or gilding, silver embossing or work on ivory or on lithographs of the city's workshops and talking photographs of some people and buildings.

The creative process is analyzed in its different phases, emphasizing the textual sources that inspired, for example, the medieval altarpieces, which need the Golden Legend for a correct understanding of the themes treated. The graphic sources also have their place when it comes to showing how some compositions literally copy the engraved model , such as the enormous canvas of the Conversion of St. Paul from the Wayside Cross of the Conceptionists that copies a Rubenian composition, widely disseminated through the engraving by Schelte a Bolswert, which was also copied by Camilo, Murillo, Berdusán and Escalante in the second half of the 17th century.

Everything related to the construction of the images and their iconographic characterization by means of collective or personal attributes is of great interest and constitutes the fourth topic treated. An exercise in this sense and through the images of the past centuries, preserved in the different temples of the city, provides the opportunity to reflect on the condensing character of the patrimony to which we have alluded before. Attributes, symbols, emblems, as well as the representations of the invocations of the Virgin, from those of the religious orders to the multiplicity of painted, engraved, lithographed and photographic portraits of the Virgin of Le Puy.

Finally, the fifth part discusses the use and function of numerous objects. A brief analysis is made of the preserved votive offerings of the Baroque period, which provide a good reason to consider some aspects of daily life, illnesses, clothing, as well as the beliefs and values of the society of the Ancien Régime. The location of architectural dependencies according to the orientation, the letters of profession and, above all, different alienated or stolen pieces, provide an opportunity to deal with the importance of one of the reasons for their execution, which was none other than to serve different purposes: work, catechization, indoctrination, apprenticeship, display of power, creation of the image of a lineage or a corporation, etc.