June 27

The Renaissance and Baroque altarpieces in Pamplona Cathedral

Alejandro Aranda Ruiz

Cultural Heritage. Archbishopric of Pamplona and Tudela

Before beginning our walk through the Renaissance and Baroque altarpieces of the cathedral, I would like to raise a series of concepts and reflections that will help us to see the altarpieces not so much as artistic goods, but as objects conceived for a use and a function. We will therefore begin by discussing the origin of the altarpiece, its meaning and its evolution.

1. The origin of the altarpiece: the altar

It is usual in common language to confuse the concepts of altar and altarpiece, being frequent the employment of the first term to refer to the second one. However, the altar and the altarpiece are two different realities, although closely related to each other.

On the one hand, there is the altar. According to the DRAE, it is "the consecrated rectangular table where the priest celebrates the sacrifice of the mass". This definition provides the three main keys that allow us to identify an altar. The first is that the altar is a piece of furniture, specifically a table. The altar would therefore be a specific subject table, like a dining table or an office table. The second core topic is its purpose. If the purpose of the dining table is to eat or the office table is to work, the purpose of the altar is to celebrate the sacrifice of the Mass, the Eucharist. But the Mass, unlike eating and working, is not considered by Christians as an ordinary activity, but as the principal act of worship, the most important thing that can happen on earth. Hence the third core topic. The altar is a consecrated table, that is, it is destined solely and exclusively for its function.

The origin of the altar is found in the early days of Christianity. During the persecutions of Christians, altars were portable wooden tables that were taken to the place where the Eucharist was celebrated. From the 4th century onwards, with the end of the persecutions, the first buildings destined exclusively for worship were created and with this the fixed and stable altar was created, which was not made of wood, but of stone, both for its durability and its symbolism: Christ as the cornerstone of the Church. Also, because of the close link between the celebration of the Eucharist and the cult of the martyrs, the custom (which later became law) of placing relics of martyrs inside or under the altar began.

But the appearance of fixed stone altars did not put an end to the existence of mobile altars. Reasons of mobility or the proliferation of numerous altars inside the churches from the 6th century onwards and the cost of making them all of stone and fixed, led to the emergence in the Age of average of a new mobile altar subject which, without having the shape of a table or being made of wood like the altars of the time of the persecutions, had the three main characteristics of the fixed altar: it was made of stone, it contained relics and it was consecrated. This is what is called an altar. The altar is a square stone, just the right size to hold the chalice and host, on which more or less the same rites were performed as when a fixed altar in the form of a table was consecrated. This altar could be placed on any support subject that simulated the shape of an altar and could be made of wood, as is the case of the cathedral altars.

Among the means of emphasizing the importance and sacredness of the altar is its decoration, which has varied over time and has included various elements. One of the first objects of ornamentation were reliquaries with relics, as seen in France(Admonitio synodalis, X centuries). The absence of relics for exhibition on the altar in the case of temples that lacked them began to be supplied with sacred images that, at first, were placed on the front of the table, on fronts of cloth, wood or more or less precious metals. The increasingly pressing need for images, in a society lacking them, meant that the images did not begin to fit on the frontal. The solution to the problem was to place them behind the altar table, painted on the wall or on a board called retro tabula, from which the Castilian word for 'altarpiece' derives. This is how the retablo came into being around the 11th century.

As we can see, it is the altar that explains the origin of the altarpiece and gives it meaning and raison d'être. The altarpiece is not a merely decorative or artistic object, but a piece intimately linked to the altar, on or behind which it is placed, contributing to serve as a background for the liturgy and to highlight the importance of the altar as a privileged place for the meeting of God with men.

2. The altarpiece: meaning and evolution

Simplifying a lot, because throughout history there have been multiple typologies, we can say that the altarpiece is a piece of furniture that is composed of two parts: the masonry and the imagery. The masonry is the structure that houses the images and usually has an architectural or building appearance. Consequently, the style of the masonry evolves with the architectural style. Thus, in the Gothic we find pointed arches, vegetal tracery and pinnacles, and in the Renaissance, pediments, architraves and columns. The images, on the other hand, can be sculpted or painted, finding sculptural, pictorial or mixed altarpieces.

The evolution of the altarpiece will be uneven, with the masonry on the one hand and the imagery on the other. Regarding the former, the process will be from less to more. The architecture of the altarpieces will gain in size and complexity with the passing of time, finding at the end of the Age average examples of great size and richness, such as the altarpieces of the cathedrals of Seville, Toledo or Oviedo. The apogee will be during the Baroque, when the altarpiece will tend to cover the entire wall to which it is attached. The imagery, however, will evolve in reverse, from more to less. In the average Age and in the Renaissance there will be very compartmentalized altarpieces, with a large number of images (preferably narrative). During the Baroque, the mazonry will gain prominence B enveloping the images, whose issue drops considerably, preferring, moreover, isolated images to scenes.

The altarpieces could be built in almost any material: stone, alabaster or marble. However, during the Renaissance and Baroque periods, the general trend in Navarre and in the cathedral was to make them entirely of wood, due to their lower cost, availability of the material and the possibility of being polychromed and gilded.

The construction of an altarpiece was an interdisciplinary business in which architecture (in the masonry and in the assembly of the pieces), sculpture (in the images and in the decorative work of carving) and painting (in the polychromy and gilding of all the parts) were involved. Of all these tasks, the most important and costly was that of polychromy and gilding, since it was decisive in giving the work its final appearance. It could be said that a good polychromy concealed a mediocre sculpture, while a bad polychromy ruined even the highest quality sculpture.

In order to fulfill its mission statement of teaching, delighting and moving behaviors, the altarpiece was interrelated with rhetoric through preaching (serving its images as exempla to the preacher), with scenography through liturgy (serving as a background for the celebration of the mass or as a stopping place for the cloister processions in certain festivities) and with music, through the interpretations of the cathedral chapel.

At final, in the altarpiece, and with it in the temple, the bulk of the people found all that they lacked in their ordinary lives: light and color, the pleasant smell of incense, the sound of music and the incomparable spectacle of the liturgy of the Roman Church. It was a foretaste of the glory promised to the faithful if they imitated the example of the saints they beheld on the altarpiece.

3. The altarpieces of the cathedral

The construction of the main altarpiece of the cathedral of Pamplona between 1597 and 1599 will be the starting signal for a process of adornment in which for a little more than one hundred years (until 1713) the interior of the cathedral will be endowed with seventeen altarpieces. Thus, to the main altarpiece will be added those of the Pietà (1600), St. John the Baptist (1611-1617), St. Benedict (1632-1634), the three of the Barbazana chapel (1642-1643), the two of St. Jerome and St. Gregory (1682), Saint Joseph (1686), Saint Catherine (1686-1687), the two of Saint Martin and Saint John the Evangelist (1699), Saint Christine (1700), the two of Saint Barbara and Saint Fermin (1712-1713), and the one of the Trinity (1713).

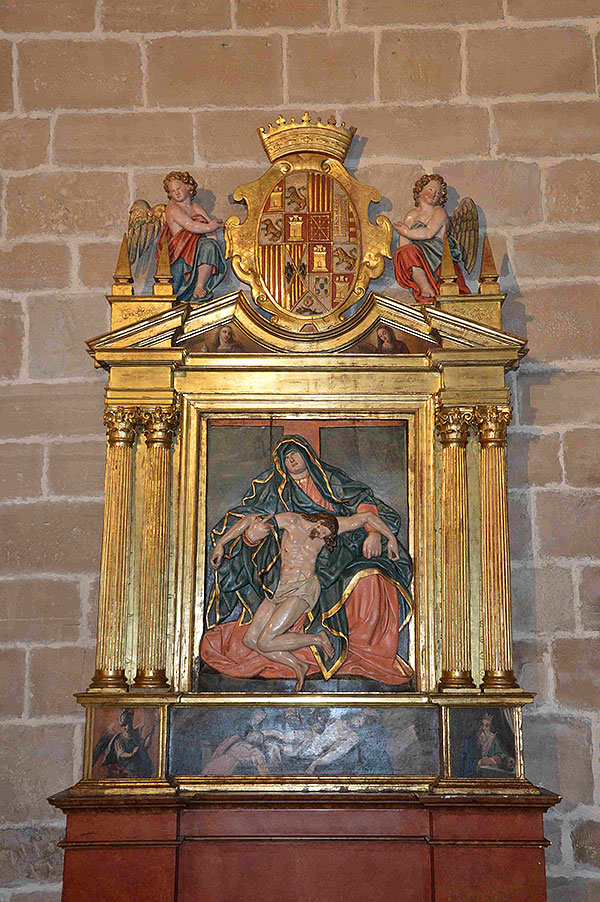

Domingo de Bidarte and Juan Claver, Altarpiece of the Pietà, 1600.

Photo: Alejandro Aranda.

This process of dressing the cathedral was the result of the efforts of different promoters. Among them are three bishops of Pamplona: Antonio Zapata (1596-1600) with the main altarpiece; Fray Prudencio de Sandoval, O.S.B. (1612-1620), with the altarpiece of St. Benedict; and Fray Pedro de Roche, O.F.M. (1670-1683), with the altarpieces of St. Jerome and St. Gregory. They were joined by the principal dignitaries of the cathedral chapter: the prior Diego de Echarren (1680-1701), with the altarpieces of St. John the Evangelist, St. Martin and St. Christina, and the archdeacons Juan de Ciriza (died 1645), with the three altarpieces of the Barbazana, and Andrés de Apeztegui (1657-1715), with the altarpiece of St. Fermín. The chapter itself was also an important promoter, either alone with the altarpieces of St. Catherine and St. Barbara, or at partnership with others, such as Bishop Roche. Personalities and corporations also contributed to provide altarpieces to the cathedral, as owners or patrons of the chapels in which they were located, such as the committee Real de Navarra, who paid for the altarpiece of the Pietà in the presbytery, considered the royal chapel of Navarra; the parish of St. John the Baptist with the altarpiece of the same saint in the chapel that was its seat; the carpenters' guild with the altarpiece of St. Joseph in the chapel of its ownership; or the Count of Lerín with the altarpiece of the Trinity in his family chapel.

Mateo de Zabalía and Miguel de Armendáriz, Altarpiece of Saint Augustine from the Barbazana, 1642-1643.

Photo: Alejandro Aranda.

Stylistically, the altarpieces of the cathedral evolve from Romanesque and late Romanesque (altarpieces of the Pietà and St. John the Baptist) to Baroque (altarpiece of St. Catherine), passing through the early Baroque or Classicist Baroque (altarpieces of the Barbazana). After the low Renaissance period, in which first-rate masters such as Pedro González de San Pedro and Domingo de Bidarte (Mayor and de la Piedad) worked, the altarpieces of the Pamplona church suffer, in general, from a retarded character, very attached to classicism and the local Romanesque tradition. Thus, for example, the Solomonic columns, whose first manifestation in Pamplona is dated around 1667 in the altarpiece of St. Joaquin of the Discalced Carmelites, do not appear until 1686 in the altarpiece of St. Catherine by Miguel de Bengoechea. The mentality of the city elites, not very open to novelties, and the pressure of the Pamplona carpenters' guild against the entrance of foreign masters meant that most of the altarpieces were made by local artists, who were not given to ingenuity and avant-garde. Quite possibly for this reason, the prior Diego de Echarren turned to the Tudela-born José de San Juan for the altarpieces of St. John the Evangelist, St. Martin and St. Christina, who satisfied the expectations of his promoter by introducing angel heads on the corbels, Solomonic columns and finely carved decoration. Not surprisingly, it was masters from other places who executed the best works, there being precedents prior to the presence of José de San Juan in the cathedral. On some occasions, the scarcity of capable sculptors in Pamplona had forced to resort to artists from outside the capital and its surroundings, such as the Cabredo-based master Francisco Jiménez Bazcardo in the case of the sculptures of the collaterals of St. Gregory and St. Jerome. The elegance of the set of altarpieces of the Barbazana, which stylistically connects with courtly models, was also due to another foreign master, the Basque Mateo de Zabalía. All this would cause that in 1712-1713, the chapter would cherish the idea of dressing the ambulatory of the temple with altarpieces by Francisco de Gurrea from Tudela, who had just made the main altarpiece of the Recoletas, a first-rate exponent of the Tudela and Navarre Baroque. His death, however, caused the altarpieces of Saint Barbara and Saint Fermin to be made by a local artist, Fermín de Larráinzar, who, on a classicist architecture typical of other times, arranged a variegated decoration characteristic of Baroque chasticism.

Regarding the iconography of these altarpieces, a walk through the cathedral allows us to verify the different criteria that existed for the choice of the different saints and invocations of the Virgin that populate the cathedral altarpieces.

The presence of certain devotions is directly linked to the promoter or promoters of the work. Thus, the altarpiece of St. John the Baptist is dedicated to this saint because he is the patron saint of the parish, that of St. Benedict because he is the founder of the order to which Sandoval belongs, that of St. Catherine because she is the patron saint of the brotherhood that owns the chapel where it is located, and that of St. Joseph because he is the patron saint of the guild that paid for the altarpiece. The presence in the main altarpiece of iconographic motifs foreign to the Navarrese tradition, such as the Imposition of the chasuble on Saint Ildefonso, is due to Antonio Zapata's stay in Toledo as a canon. In the same way, the placement in a place of honor (the central street of the second body) of Saint Anthony in the altarpiece of Saint Jerome, of Saint Augustine in the altarpiece of Saint Gregory and of Saint Andrew in the altarpiece of Saint Fermin is due to the fact that the first was the founder of the order to which Bishop Roche belonged, the second was the patron saint of the chapter and the third was the saint of the name of Andres de Apestegui.

Miguel de Bengoechea, Juan Munárriz and José Munárriz, Altarpiece of Santa Catalina, 1686-1687.

Photo: Alejandro Aranda.

Some saints and invocations can be explained by the existence of previous altars and altarpieces from which they were borrowed. This is the case with San Fermín and San Gregorio and the same with San Martín (chapel founded by Martín de Zalba around 1377-1403) and San Juan Evangelista (chapel founded by Sancho Sánchez de Oteiza around 1420).

On the other hand, other iconographies can be related to the traditions of the chapter and the particular history of Pamplona, Navarre and Spain. The presence, for example, of the relief of the Slaughter of the Innocents on the altarpiece of Santa Catalina would be related to the statio or stop made in that same place by the cloister processions celebrated by the chapter on the occasion of this festivity. The relief of St. Sebastian, placed in the altarpiece of St. Gregory, replaced an image of bulk carved in 1600 by Domingo de Bidarte commissioned by the City Council of Pamplona, which since that year celebrated the feast of this saint in the cathedral in gratitude for the end of the plague of 1599. Likewise, Saint Babil, legendary bishop of Pamplona, placed in the altarpiece of Saint Catalina, would also connect with the history of the city, like Saint Saturnino located in the altarpiece of Saint Jerónimo, patron saint of Pamplona and to whom the city council made a vow in 1611. The relief of St. Francis Xavier, whose placement in 1682 on the altarpiece of St. Jerome was a symbol of the recognition of his board of trustees on Navarre by the chapter, is related to the particular history of Navarre. The Immaculate Conception of the altarpiece of St. Catherine, sworn by the Cortes Generales in 1621 and proclaimed co-patron saint of Navarre by the same Cortes in 1765, can also be related to Navarre. On the other hand, Saint Teresa of Jesus and Santiago Matamoros of the altarpiece of Saint Catherine, as well as Saint Ferdinand of the altarpiece of Saint Jerome, would be linked to devotions typical of the Spain of the time, the first being patron saint of Spain, the second more or less unofficial patron saint of Spain, and the third patron saint of the Monarchy.

The altarpieces of the cathedral also hosted popular devotions such as Saint Anton (Saint Jerome altarpiece), Saint Barbara, Saint Agatha (Saint Barbara altarpiece) and Saint Michael (Saint Barbara and Saint Fermin altarpieces), and saints linked to the spirituality of the Counter-Reformation, as founders (St. Philip Neri and St. Ignatius of Loyola in the altarpiece of St. Barbara), saints who exemplified virtues such as repentance (St. Mary Magdalene in the altarpiece of St. Catherine), charity (St. Thomas of Villanova in the altarpiece of St. Jerome) or ascetic practices (St. Peter of Alcantara in the altarpiece of St. Barbara).

Finally, there are iconographic motifs that can be related to the function of the altarpiece, such as the Pietà, which was intended to host the celebration of masses in suffrage of the kings; hence the allusions to death (Pietà, Burial of Christ and St. Michael, in charge of weighing the souls) and to the Monarchy (St. Louis of France and the royal coat of arms).

4. Epilogue

The arrival of neoclassicism and the Enlightenment meant that, at the end of the 18th century, coinciding with the construction of the main façade, the canons began to take a dim view of many of the altarpieces they had treasured over the centuries. Treatise writers such as the Marquis of Ureña were not only critical of the Baroque style, but also proposed new ideas, such as reducing the number of altars at issue or eliminating choirs and grilles. Economic reasons prevented the chapter from immediately executing all the plans it would have liked. In the decades of 1800-1820 they had to be content with the suppression of the four altarpieces of St. Martin, St. John the Evangelist, St. Christina and the Trinity, and their replacement by other neoclassical ones. However, it was during the first half of the 20th century when an authentic revolution of the interior of the cathedral was carried out with the suppression of the neoclassical altarpieces, the main altarpiece of the church and the main altarpiece of the Barbazana, and the change of location of a good part of those that survived (two of the altarpieces of the Barbazana, the altarpiece of St. Joseph and the altarpiece of the Pietà). But that is another story.