The piece of the month of January 2009

CONSIDERATIONS ABOUT A PORTRAIT OF EDUARDO CARCELLER: "EL RAPAPOBRES" (1870)

Pablo Guijarro Salvador

Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

In the Museum of Navarre there are two portraits of Tudela characters, "El rapapobres" (1870) and "Un monaguillo de la catedral de Tudela" (1871), given by their author, Eduardo Carceller (1844-1925), to the Commission of Monuments of Navarre for the museum opened by that institution in 1910. Of Valencian origin, Carceller occupied from 1874 the place of professor of drawing of adornment and figure in the School of Arts and Trades of Pamplona. From his biography we know that he studied at the School of Fine Arts in Valencia and at the Special School of Painting, Sculpture and Engraving in Madrid, and that his works were recognized with various awards as well as an honorary accredited specialization in the National Fine Arts exhibition of 1866. His specialties were history painting and portraiture, developing a style based on the academic formulas and conventions in accordance with his training. In his portraits, realistic and sober invoice, he liked to recreate classical works by great masters such as Velázquez and Murillo. In fact, it is known that in his early years at work he executed several copies of paintings by both painters.

With this participation in the section "pieces of the month" of the Chair de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro we intend to show two aspects related to this portrait: firstly, how Eduardo Carceller arrived in Tudela and secondly, who was the portrayed. With the answer to these questions, it will be possible to evaluate this work in an interdisciplinary way that includes historical, artistic and iconographic aspects, beyond merely stylistic issues already known.

Eduardo Carceller taught at the Tudela School of Drawing between 1870 and 1874. This center had been created in 1838 on the initiative of the Sociedad Económica de Amigos del País, one of whose members was Miguel Sanz y Benito, a painter who had worked as a teacher-director of the Pamplona School of Drawing between 1828 and 1837, and who would be its first teacher. The teaching of drawing was paid for by the above-mentioned Economic Society, the city council and the board of trustees Castel Ruiz, who administered the capital bequeathed to the city in 1797 by Manuel Castel Ruiz for the foundation of a high school. Line, ornamental and figure drawing were taught, although in some years the program included other subjects. The school had a large collection of plates and plaster casts, and prizes were awarded annually to the most outstanding students. In 1869 the place teacher's position became vacant and the city council decided call a civil service examination, whose exercises were sent to the Special School of Painting of Madrid. The tribunal, presided over by Federico de Madrazo, considered that none of the candidates had sufficient merit to fill the post.

Such was the interest of the City Council of Tudela in the School of Drawing that it entrusted the aforementioned Special School of Madrid with all aspects related to the civil service examination. Thus, the call for applications was published in the Gaceta de Madrid and the Diario de Avisos and the tests were held in Madrid between April and May 1870. In this way, it was possible to get the highest quality candidates from all over Spain to present themselves for the place , not only from Tudela, as in the failed civil service examination of the previous year. A tribunal formed by outstanding personalities of the artistic panorama of the moment: Bernardo López Piquer, Germán Hernández Amores, Joaquín Espalter, Ponciano Ponzano, Francisco Torras y Armengol and José Vallejo, presided by Federico de Madrazo, determined that Eduardo Carceller had been the best of the eight candidates presented. Therefore, a professor of a much higher level than his predecessors arrived in Tudela, endorsed by the composition of the panel that chose him.

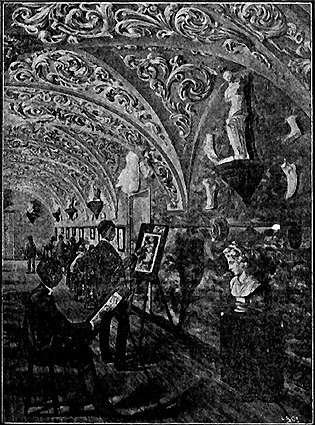

Tudela School of Drawing (La Avalancha, July 24, 1904)

The four years that Carceller remained at the head of the Tudela School of Drawing were marked by economic problems. The Economic Society had stopped contributing, the board of trustees Castel Ruiz lacked funds and only the city council contributed money. Even Carceller himself had to convince the municipal authorities to keep the center open. However, it was closed when he obtained the place of professor of the School of Arts and Crafts of Pamplona in 1874, not reopening until 1883. The School of Drawing was fundamental for the training of the young people from Tudela in the 19th century, as it is said in a document of the Economic Society (1885): "From there came out those good people from Tudela who have figured so worthily in the Artillery and Military Engineers corps, in the centers of teaching, in the careers of Industrial Engineers, branches of public works and in other industries and workshops that they created with the knowledge acquired in these schools". The Society forgot to make reference letter to those who developed a properly artistic degree program , since in it and its continuators were formed the most outstanding painters of Tudela, such as Nicolás Esparza, Miguel Pérez Torres or César Muñoz Sola.

Real Casa de Misericordia de Tudela (today hotel AC Ciudad de Tudela)

As for the second question, who was the rapapobres, the answer is given by José María Iribarren in his Navarrese vocabulary: "Asylum seeker of the Misericordia de Tudela who watched over the population to prevent public begging. He wore as a badge of his position a wide white leather bandolier and a wooden sword". The Royal House of Mercy of Tudela was inaugurated in 1791, thanks to the capital donated by the couple formed by Ignacio de Mur and María Huarte. The goal of the hospice was to take in the poor, both those who were truly poor and those who pretended to be so in order to live on alms. issue The truth is that it was never able to fulfill its mission: the building was very small in comparison with the high number of poor people in the streets of the city and it never achieved a healthy economic status . After a few years of total decadence, in the middle of the 19th century the Misericordia restored its foundational building -from which it had been expelled- and notably increased the number of inmates issue . On this occasion, new statutes were drawn up in 1855, from which it is clear that, basically, the problem of poverty and its consequences had hardly changed in sixty years. "The arrangement of customs, the regular method of life, a well ordered food, preserves the poor from many diseases that they acquire with their untidy life in vagrancy, poorly fed and well drunk, of which experience gives us examples every time they become beggars, they become skinny, emaciated and discouraged beings, who will soon end their miserable existence in the Holy Hospital".

Eduardo Carceller, "El rapapobres", 1870. 38,5 x ,5 cm.

Museum of Navarra (Photograph: Larrión & Pimoulier).

The persecution of this subject of people would be the task of the rapapobres. The aforementioned statutes establish that two of the hospitians of "more probity and disposition " "will go out every day to walk through the town carrying a badge and will watch that no one else begs for alms or wanders through the streets and taverns, which they will try to prevent and, if they cannot achieve it by themselves, they will implore the help of the ministers of justice". The rapapobres must have become a regular presence in the streets of Tudela, to the point of attracting the attention of Eduardo Carceller and becoming the protagonist of one of his portraits. He is portrayed bust-length, with a white leather bandolier and the badge of the Casa de Misericordia, and with the clothing worn by the inmates: brown cloth jacket and pants. We are, therefore, before a poor man confined in a hospice, but who has been represented dignified, impregnated with a profound human quality that distances him from those beggars who populated the street life of Spanish cities. His look conveys a certain melancholy, a reflection, perhaps, of the terrible life experiences that characterized the biographies of these characters. It is reminiscent of those street types, at the same time dressed in a severe nobility that served Velázquez or Ribera -it is known that they influenced Carceller- to represent apostles or philosophers. Even the style of this painting: naturalism, intense light contrast with a powerful spotlight that illuminates the features of the character and leaves the background in the shadows, etc., reminds us of those masters.

bibliography

MANTEROLA, P. and PAREDES, C., Arte Navarro, 1850-1940. Un programa de recuperación de las Artes Plásticas, Pamplona, Gov. of Navarre, 1991.

OSSORIO Y BERNARD, M., Galería biográfica de artistas españoles del siglo XIX, Madrid, Giner, 1975.

QUINTANILLA MARTÍNEZ, E., La Comisión de Monumentos Históricos y Artísticos de Navarra, Pamplona, Gov. of Navarra, 1995.

URRICELQUI PACHO, I. J., "La primera generación de pintores navarros contemporáneos: aportaciones para un Catalog de sus pinturas en el Museo de Navarra", file Español de Arte, nº 300, 2002, pp. 381-396.

ARCHIVES

file Municipal of Tudela. Friends of the Country Fund.