The piece of the month of December 2013

AN EXAMPLE OF GREEN MAN IN THE CHAPEL OF SAN FERMIN IN PAMPLONA

José Luis Molins Mugueta

Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

The Chapel of San Fermín: construction and renovations

The desire to erect a worthy shelter for the reliquary image of San Fermín led the Pamplona City Council to become the promoter of his chapel, annexed to the parish church of San Lorenzo, which was to be built between 1696 and 1717, according to plans by the tracists Santiago Raón, Fray Juan de Alegría and Martín de Zaldúa. In the financing, endowed with funds from the municipality and channeled through the exercise of its board of trustees, also participated Pamplona and Navarrese of diverse condition, some residents in Madrid, mostly members of the Royal Congregation of San Fermín de los Navarros, constituted in the Court in 1684; and many others, dispersed in the Indies. It is, therefore, an example of collective, institutional and popular business , which is on the verge of its third centenary.

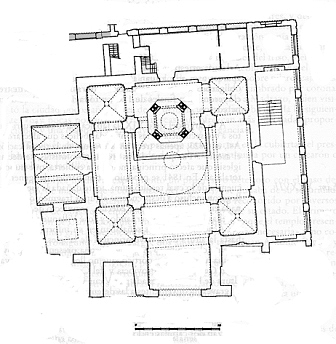

General view of the Chapel of San Fermín

The plan and elevation of the building are typically baroque, as is evident from the exterior: it is a Greek cross inscribed in a square, embraced by a double wing with pretensions of a palace, on two floors, the lower one of stone with large arcades, and the upper one, of brick and with straight openings, one and the other latticed. The external walls of the cross are topped by triangular pediments, a form required by the gable roofs. The center is occupied by the octagonal drum, which supports a slender lantern, the latter rebuilt for the last time between 1823 and 1824.

In 1795 the average orange and lantern collapsed, resulting in a gap of considerable proportions. As soon as it was possible, it was possible to think of undertaking the necessary reconstruction; and at the same time, to adapt the ornamentation of the chapel to the new academic taste, far from the original baroque style. The reconstruction was awarded to Santos Ángel Ochandátegui, according to the project and the plans he had signed in December 1797. This man from Durango was Ventura Rodriguez's right-hand man in Navarre: he had directed the bringing of water to Pamplona from Subiza and now he was in charge of the direction of the works of the new façade of the cathedral, two projects conceived by Rodriguez, essential to know the implementation of the Academicism in this Kingdom. The works, following Ochandátegui's plan, were extended between 1800 and 1805, beginning with the reconstruction of the average orange and lantern, to continue with the new ornamentation: medallions in the pendentives, substitution of the old tribunes with lattices for balustraded balconies; at the same time the profuse baroque decoration of entablatures and vaults was succeeded by the current sober motifs, of academic lineage; and the bases of the pillars, simplified. The position of the temple, previously centered towards the chancel, was also moved back. The windows were replaced by oculi, the doors of Wayside Cross and the great access arch from the nave of San Lorenzo were modified. The taste of the time brought sculptural reliefs with episcopal motifs and a medallion with the scene of the martyrdom of the Patron Saint over these openings. This radical interior reform makes the chapel of San Fermín an important milestone of the progressive academic influence on Navarrese architecture, in the gradual implementation of neoclassicism, a style destined to have an intense and long lasting influence in this land.

Plan of the Chapel of San Fermin (CMN)

The arch that appeared in 2008 is marked in gray at the top.

The Sanferminero green man

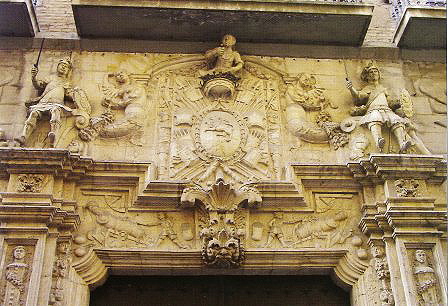

Ochandátegui's reform of the exterior was of less importance, although it was also important. In fact, we are going to deal with a specific plastic aspect located here. The aforementioned quadrangular body of the building has four sides, although it only has two -unequal in length-, since the other two are occupied, on one side by the church of San Lorenzo, and on the other by the farmhouse. The bay aligned with the door of the parish church has eight arches, while the other has six, of which the last one is partially embedded in the residential building, which corresponds to issue 18 of the Rincón de la Aduana. A painting by Miguel Sanz Benito, conserved in the file Municipal de Pamplona, which represents the episode at the time of O'Donnell's uprising in October 1841, graphically testifies to this aspect as already existing at that time in the 19th century.

Aspect of the exterior arches of the Chapel of San Fermín in the mid-19th century.

(M. Sanz Benito, Sublevación de O'Donnell en 1841, detail.

file Municipal of Pamplona)

But beyond that there is another arch, which appeared relatively close to the present date, in the spring of 2008, when the wall that concealed it was demolished in the course of interior renovation work at portal. It does not differ from the preceding ones, nor does the upper part of the entablature that is visible. The opening is sample blinded by a brick wall; and in it we can see the mark of an old solid circular oculus and perhaps also the imprint of an earlier rectangular opening (we should remember that oculi were common in the building during its neoclassical renovation from 1800 to 1805). One cannot affirm or deny the existence of another arched opening that continues the sequence, without first accessing a certain space of the portal, which remains hidden. But what is certain is that the councilors of 1696 conceived the perimeter circuit of the chapel as a stage for processions, when bad weather prevented them in the streets.

Blind arch appeared inside portal, with traces of oval and rectangular window.

However, the finding would not be of great importance if it were not for the plastic motif that exhibits the core topic of the arch as an ornament: none other than the representation of a green man, known topic of great diffusion in time, geography and cultures. It is the representation of a human face by means of the employment of vegetal elements, like scrolls, which, in this case, frame the eyes, in the form of a tuft on the forehead and aladares on the position of the temples; as well as those located instead of cheeks and lips, around the mouth, in which teeth and language are naturally signified. As so often happens in sculpture, the protruding nose has disappeared, the victim of time or an occasional unfortunate blow. The sculpted subject is an easily carved limestone, of a whitish tone, well differentiated in chromatic tone from the neighboring grayish voussoirs. This mask retains perceptible traces of black paint on the eyeball, which, like the iris and pupils, would accentuate the expression of the eyes.

The green man located at core topic of the preceding arc

It seems that each and every one of the exterior arches of the chapel had its corresponding green man, sculpted in the respective core topic. In fact, today one can appreciate the employment of the same whitish stone for all the central voussoirs. Undoubtedly, for Ochandátegui's architectural statement of core values it was essential to purify the arcades of anecdotal elements of baroque lineage, dispensing with masks that were felt to be caricatures. To this end, the keystones were chiseled, which made it possible to match their surface with the smooth course of the threads without further complication.

Photographic composition of the arches, with green man incorporated.

Moreover, in the initial project of Raón and consorts, the openings of the stone arches may have been solid brick, with rectangular slit windows, which were converted into oculi during the renovations undertaken between 1800 and 1805. In 1806 the Cathedral Chapter sold the iron grilles -331 arrobas and 25 pounds in weight- from the chapels of the then-reformed cathedral, to make, after casting, the gratings that now close the gallery leave of the exterior circuit of the Chapel of San Fermín. The arches were then left diaphanous and open to the air, as clearly attested by the aforementioned picture, painted by Sanz Benito in 1841, in all its arches, except for the one that has remained hidden until now, which remains as a witness of the preceding status .

Green man: meaning and background

Allow me a reference letter as a simple framing, necessarily brief, because the topic of the green man has been and is the subject of numerous programs of study and approaches, ranging from the scientific to the esoteric and, therefore, the bibliography is copious. The origin of the term is due to the Englishwoman Julia Somerset, née Hamilton, better known by her marriage as Lady Raglan, who published in 1939 in "Folklore Journal" the article The Green Man in Church Architecture. In it, the green man is defined as the representation of a human face, obtained totally or partially by the employment of vegetal elements -preferably leaves of plants to which flowers or fruits can be incorporated-, whose sprouts start from the mouth, nose or eyes, to describe whimsical convolutions in the form of hair, beard, ears or other parts of the face. The presence of this motif in cultures far removed in time and space, such as India or ancient Iraq, is surprising. The "green man" appears frequently related to deities of vegetation and can be conceived as a symbol of the periodic rebirth of nature in spring and, therefore, propitiator of crops and fruits of the earth, essential for the survival of man.

Vegetable masks from: Jain temple (Rajasthan, India), 8th century. Cluny Abbey (France), 13th century, three drawings by V. de Honnecourt. Bamberg Cathedral (Germany), 13th century.

What is certain is that examples are documented in the Roman and Byzantine arts, which transmitted the model to the medieval Christian world. In the West, it proliferated throughout the Romanesque and Gothic periods at an increasing rate. In the Germanic countries it is called blattmaske, and in France, the masque feuillu; which gives notion of its expansive capacity. Without forcing concepts, it can be linked to Christ, both for attributing to him apotropaic capacity -that is to say, propitiator of goods and repeller of dangers-, and for his more transcendent character, of rebirth and resurrection. Thus, leafy masks appear in European religious architecture, albeit in secondary places, decorating corbels, capitals, arch keystones; and also in furnishings, adorning, for example, some choir stalls' mercy seats. A significant example of masque feuillu representation on parchment is the Livre de portraiture ( c. 1235 A.D.), preserved in the Library Services National of France, work of the itinerant mason Villard de Honnecourt. This master, born in the French region of Picardy, traveled through various European countries, taking notes and drawings of aspects of Gothic constructions, in his opinion of singular interest.

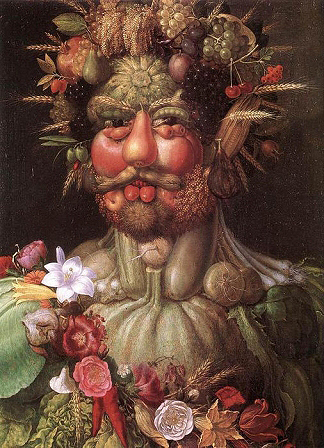

The application by the bishops of the criteria approved at the Council of Trent on the veneration of the relics of the saints and of the sacred images, adopted at the XXV session, on December 3 and 4, 1563, by providing that nothing profane should be seen in the temples, meant in fact the end of the green man in religious architecture. This was true in countries of Catholic obedience, but not in Protestant countries, as is the case of Great Britain, a continuing example, which continues to this day, of secular adherence to this plastic matter. However, the leafy mask had no problem for its representation in the field of civil architecture of Catholic nations, enduring in the architecture of palaces, villas and gardens, with abundant examples, especially in the French Renaissance or during the German Romanticism. In Italy, at the end of the 16th century, the fantastic mannerism led Giuseppe Arcimboldo to execute whimsical portraits based on skillfully combining plant elements of meticulous individual depiction.

Arcimboldo, Portrait of Emperor Rudolph II as the god Vertumnus, 1590

The presence of the green man in Navarre

Medieval Navarre is no stranger to the presence of the green man in its Templar architecture. This is supported by the examples on corbels at the head of the Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Love of San Miguel, in Ujué; it is an early Gothic building, from the 13th century, with still Romanesque reminiscences, inspired by French models from the Midi. More accredited specialization for its peculiarity, aesthetic quality and Degree of conservation deserves the green man located in the exterior archivolt of the doorway of Santa María, of Olite, a work close in date to 1300. This "leafy man" has a possible double lineage: on the one hand, the subject itself, so much of the insular taste, added to the presence on the doorway of some decorative details, scarce in France and frequent in England, lead us to think of an English origin (especially if we consider at that time the contiguous proximity of Navarre with the Duchy of Aquitaine, then belonging to the British crown). But on the other hand, the Kingdom of Navarre moved in the French orbit and in fact Philip the Fair, married to Joanna I, became king of France and Navarre in 1285; and the House of France would also reign in Navarre until the death of Charles the Bald in 1328. This is a historical argument of some solidity to defend the direct French filiation of the green man of Olite, by means of the adoption of inspiring models coming from the Parisian area .

Green man on the façade of Santa María de Olite (c. 1300)

The Navarrese references to topic in the first half of the 14th century can be closed with the triple accredited specialization of the green man existing in the cloister of the Cathedral of Pamplona: one sculpted on the inner face of the lintel of the Amparo Door; and the other two, in two corbels of what was conference room capitular, popularly known as Barbazana Chapel (due to being the burial place of the bishop Arnaldo Barbazán, deceased in 1355). In these two masks the two sexes are represented, the masculine, properly green man, and the feminine, green woman, much less frequent. Specialists attribute their carving to William English, whose nickname indicates his origin, a British sculptor with possible professional pathway in Normandy and Aquitaine, who also worked on the Cathedral of Huesca (1338) and whose facade is attributed to him.

Corbels of the conference room capitular (Barbazana Chapel) of the Cathedral of Pamplona.

All these examples of medieval Navarrese art coincide with the green man of the Chapel of San Fermín only in the topic, confirming the success of a motif that reaches our days without any conceptual charge; today it can be found as a claim of an ecological entity as well as an ornament of a faucet or a doorknob. It already had the same meaning, merely ornamental and far from symbolic ideology, in the baroque architecture of the early eighteenth century.

In the Calle Mayor of Pamplona, between 1709 and 1716 the façade of the palace of the Marquises of San Miguel de Aguayo, until recently known as high school de Teresianas, a building very close to the Chapel of San Fermín, inaugurated in 1717, was finished. Precisely on the lintel of its façade there is a representation of a green man. The proximity of both constructions and their coincidence in time leads us to think that the repetition of the same plastic motif responds to something more than mere coincidence. The affection and good judgment, already demonstrated, of the neighbors of portal where it has appeared and, in final, to the Administrations responsible for the defense of the Pamplona and Navarre heritage, is responsible for the conservation of the Sanferminero green man.

Representation of green man on the lintel of the façade of the palace of the Marquises of San Miguel de Aguayo in Pamplona.

bibliography

-ANDUEZA UNANUA, P., La arquitectura señorial de Pamplona en el siglo XVIII. Families, town planning and city. Pamplona, Government of Navarra-Principe de Viana Institution, 2004.

-FERNÁNDEZ-LADREDA AGUADÉ, C., "El gótico navarro en el contexto hispánico y europeo" in -Cuadernosde la Chair de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro, 8. Pamplona, Chair de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro. University of Navarra, 2008

-GARCÍA GAÍNZA, M.C. AND OTHERS, Catalog Monumental de Navarra. III, Merindad de Olite. Pamplona, Institución "Príncipe de Viana", Archbishopric of Pamplona, University of Navarra, 1985.

-GARCÍA GAÍNZA, M.C. AND OTHERS, Catalog Monumental de Navarra.V***, Merindad de Pamplona. Pamplona. Pamplona, Institución "Príncipe de Viana", Archbishopric of Pamplona, University of Navarra, 1997.

-MOLINS MUGUETA, J. L., Chapel of San Fermín in the Church of San Lorenzo de Pamplona. Pamplona, Diputación Foral de Navarra-Institución "Príncipe de Viana", Pamplona City Council, 1974.

-URANGA, J.E. and ÍÑIGUEZ, F., Arte Medieval Navarro, vols. 4 and 5. Pamplona, Caja de Ahorros de Navarra, 1973.