The piece of the month of April 2014

A PORTRAIT OF MANNERS BY THE NAVARRESE PAINTER EMETERIO TOMÁS HERRERO

Iñaki Urricelqui Pacho

Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

Durante el tránsito del siglo XIX al XX, la pintura costumbrista alcanzó en Navarra un importante impulso, similar al que recibió en el resto de España. Dentro de la primera generación de pintores contemporáneos navarros, nacidos con anterioridad a 1875, destacaron en este género figuras como Eduardo Carceller, Nicolás Esparza, Andrés Larraga o Inocencio García Asarta -estos dos últimos, sin duda, los pintores navarros más interesantes de su tiempo-. A ellos les seguirían los integrantes de una nueva generación, denominada “generación puente”, entre la que destacaron en el género costumbrista autores como Javier Ciga, Miguel Pérez Torres o Francisco Echenique. Fueron pintores nacidos entre 1875 y 1900, formados en focos nacionales (Madrid, Barcelona) e internacionales (Roma y París), que desarrollaron una pintura que, pudiéndose calificar de tradicional (por la importancia concedida al dibujo, a la composición, al uso de un cromatismo realista y sin estridencias), coincidió con la estética moderna en el uso de una pincelada suelta, de sabor impresionista, y en el interés por temas de actualidad. De este modo, combinaron un “casticismo” en lo temático, con atención a lo local y cotidiano, con una pintura que sin ser moderna resultó tal para el ambiente artístico navarro y, en algunos casos concretos, alcanzó verdadera modernidad pictórica, como sucede con Javier Ciga o Jesús Basiano.

A esta segunda generación de pintores navarros pertenece Emeterio Tomás Herrero, nacido en Mendaza en 1886. Gracias a su solicitud de una pensión para formación artística elevada a la Diputación foral y provincial de Navarra el 27 de septiembre de 1905 sabemos que cursó estudios durante cuatro años en la Escuela de Artes y Oficios de Pamplona bajo la dirección de Enrique Zubiri, en cuyo estudio particular también recibió lecciones. En certificado del propio Zubiri, adjuntado a su solicitud, el maestro pamplonés expresaba: “he podido apreciar sus extraordinarias facultades en la Copia del Antiguo, sus rapidísimos progresos, su excepcional talento para el arte á que se dedica”. Aparte, durante los meses de febrero a mayo de 1905, estuvo matriculado en la Escuela Superior de Barcelona, recibiendo clases de Vicente Borrás, que certificaba sobre el joven navarro sus “muy visibles adelantos gracias á su constante aplicación y clarísimos dotes que ha demostrado”. La pensión solicitada por Emeterio Tomás tenía como objetivo permitirle matricularse en la Escuela de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, “con el fin de hacer más llevadera esta difícil y costosísima carrera” puesto que, en caso de no recibirla, “se vería privado de algún triunfo que pudiera conseguir durante ella y tal vez tener que abandonarla por no poder hacerla con la rapidez que debiera”. Pese a todo, la Diputación acordaba el 28 de noviembre que se le denegara la ayuda. No obstante esta decisión, hay que precisar que no se debía tanto a las aptitudes del solicitante, que eran notables a juzgar por los informes adjuntados a la petición, sino al hecho de que la corporación provincial no contaba en esas fechas con un sistema estable de ayudas a la formación artística que, habiendo sido ensayado sin mucho éxito en las décadas de 1880 y 1890, no se concretaría mediante un reglamento hasta la década de 1920.

Pese a esta negativa, Emeterio Tomás no cejó en su empeño de viajar a Madrid y, por noticias aportadas por su familia, finalmente acudió a la Escuela de San Fernando, posiblemente como alumno libre, esto es, sin matrícula oficial pero con acceso a determinadas clases. Aparte, también gracias a esta fuente, conocemos que viajó a París con ayuda económica familiar, precisamente en el contexto histórico en el que allí confluían la herencia del Impresionismo y de las tendencias estéticas de fin de siglo, con la propuesta de vanguardia de movimientos como el Fauvismo, el Expresionsimo o el Cubismo.

Finalizada su formación artística, Emeterio Tomás se instaló en Estella, localidad en la que permanecería toda su vida. Allí abrió su estudio, dedicándose a la pintura, especialmente el retrato y la escena costumbrista, muchas veces combinando ambos géneros en lo que podría denominarse “retrato costumbrista”, así como el paisaje. Sus trabajos revelan a un artista bien dotado y capaz de captar la esencia de la figura y de la escena. Inmerso en el ambiente artístico de su época, tuvo relación con Gustavo de Maeztu y con Jesús Basiano, dos referentes de la pintura en Navarra de su generación.

Como sucedió con otros pintores, Emeterio Tomás acabó derivando hacia la fotografía, abriendo un estudio fotográfico en la Plaza de los Fueros de Estella y convirtiéndose en un notable retratista. Una fotografía, posiblemente de los años 30-40, nos muestra al pintor-fotógrafo trabajando en su estudio, rodeado de sus retratos fotográficos y de algunas de sus pinturas, entre otras, la que vamos a comentar a continuación. Emeterio Tomás Herrero fallecía en Estella en 1954 dejando un importante legado pictórico y fotográfico que bien merece un estudio.

Emeterio Tomás Herrero in his studio-workshop. Decade of 1930-1940

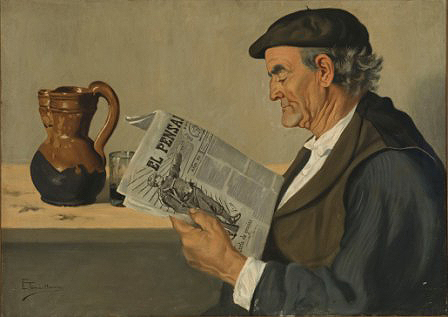

The Museum of Carlism has among its holdings a painting by this artist from Estella, hitherto unknown, which since April 15 has been on display, along with other objects, at the temporary exhibition "Comprometidos con la Historia. Donations and deposits in the Museum of Carlism", open until February 15, 2015. It is a painting that, in the wake of artists like Javier Ciga and Miguel Pérez Torres, delves into the local customs through an everyday scene such as reading the newspaper. In a simple composition there is a half-length figure, from profile, seated and dressed in a white blouse, blue camisole, brown vest and black beret, reading a copy of El Pensamiento Navarro. On the table, next to him, there is a simple still life consisting of an earthenware jug and a crystal glass with a third of red wine. It is a simple and placid scene in which an everyday moment is presented, dominated by ochre tones and a general light that shades the volumes.

This topic, the reading of the press (as well as the reading of letters, books and other writings) was habitual in the costumbrismo of the period between centuries, but far from being an anecdotal fact, it makes possible a deeper reading of the work and brings us closer, in this case, to the familiar and daily world of Carlism, as a relevant social and political movement in Navarre at the beginning of the 20th century. In this way, as in other costumbrista paintings by authors such as the aforementioned Ciga or Pérez Torres, the costumbrista scene acquires a meaning that goes beyond what is represented and delves into its historical, social and ideological context.

El Pensamiento Navarro was founded in 1897 in Pamplona as the successor of La Lealtad Navarra and was directed in its first stage by Eustaquio Echave-Sustaeta. It was born as a "Carlist newspaper" being subtitled from 1911 as "traditionalist newspaper". It was the organ of expression of Navarre's Carlism until its disappearance in 1981, thus becoming part of the daily life of many homes for almost a century. This newspaper, read by a character, leads us to think about the possible relationship of this character with Carlism.

Emeterio Tomás Herrero, Portrait of José Miguel, honorary lieutenant, reading Pensamiento Navarro, ca. 1912.

Museo del Carlismo (Deposit of Fernando Tomás Abaigar and Ana Tomás Rodríguez)

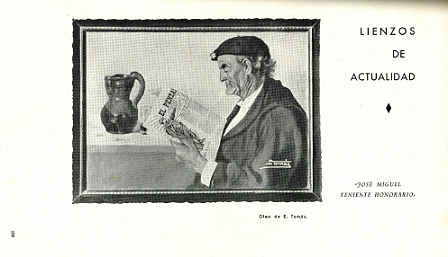

The painting in question was reproduced in 1940 in the magazine Vida Vasca with the degree scroll "José Miguel, honorary lieutenant", but it included some photographic retouching, particularly in the beret, to which officer's stars were added. With this, the identity of the portrayed person was emphasized, who was identified as a requeté and therefore, as a participant in the Spanish Civil War. However, several facts help us to qualify this. Firstly, the photograph of Tomás Herrero's studio that we have mentioned and which includes this painting, the sample as we know it today, without the stars on the beret. Therefore, the reproduction published in Vida Vasca should be interpreted as a "photographic montage", for propaganda purposes, from the original painting. In addition, the front cover of the newspaper reads "Year XV", which allows us to date the painting to around 1912, that is, 15 years after the appearance of the newspaper in 1897. This is confirmed by the image of the requeté that appears on the masthead of the copy of El Pensamiento Navarro that the portrayed person is looking at and that was common in the Carlist press at the beginning of the 20th century. The same can be said of the Carlist trilemma "God, Fatherland and King", part of which we read on the page.

As for the identity of the portrayed person and his condition of "honorary lieutenant", this must rather allude to his participation in the last Carlist war (1872-1876) in the ranks of Don Carlos VII. Thus, the scene represents a veteran of the Carlistadas (although wearing a black beret and not the Carlist incarnate) reading the organ of expression of Carlism in Navarre and, in this way, informing himself of the events of his time. The image of the Carlist soldier or "requeté" on the masthead also situates us in the process of paramilitarization that accompanied the development of Carlism during the mandate of Jaime de Borbón (Jaime III), between 1909 and 1931, a prelude to the Republican era and the participation of the "requeté" in the Spanish Civil War.

Publication of Emeterio Tomás Herrero's painting in the magazine Vida Vasca, 1940.

SOURCES

-file General de Navarra, AAN DFN CJ 37417: transcript by Emeterio Tomás Herrero.

-Conversation held with Fernando Tomás Abárzuza, in Estella, November 13, 2013.

bibliography

- Committed to History. Donations and deposits in the Museo del Carlismo (Catalog from exhibition), Pamplona, Government of Navarra, 2014, pp. 24-25.

- IMBULUZQUETA, G., Periódicos navarros en el siglo XIX, Pamplona, Gobierno de Navarra, 1993.

- URRICELQUI PACHO, I., "Pintura costumbrista en Navarra en el período 1875-1940: aproximación a un género pictórico", Ondare, n. 27, 2009, 407-496.

- URRICELQUI PACHO, I., La pintura y el ambiente artístico en Navarra (1873-1940), Pamplona, Government of Navarra, 2009.

- Basque Life. Revista Regional Española, nº XVII, 1940, p. 159.