The piece of the month of May 2016

A SUNDIAL IN THE VILLAGE OF MÉLIDA

Juan Manuel Garde Garde

PhD in Biological Sciences

When all localities are struggling to install modern digital clocks in their streets and squares, the town of Mélida has just erected a sundial in the new park next to the cemetery. The installation of this sundial in the 21st century would be nothing more than an anachronism if it were not for the fact that the municipality and its town council have wanted with this gesture to recover the report and pay homage to the "Santo Hospital de la villa de Mélida" from whose building, now disappeared, the sundial comes from.

The Holy Hospital of the town of Mélida

Like many other towns in Navarre, Mélida had a Charity Hospital, which has been documented since the 16th century. An administrator managed its accounts and a hospitaler -often a woman- attended to the needy, all under the control of the Patrons: the parish church and the town council. For at least four centuries, the hospital carried out an important work in helping passers-by, beggars and needy neighbors. Its task was especially commendable in the 19th century, during the various wars that ruined the town and the cholera epidemics that devastated it.

The location of the hospital within the town center changed throughout its history, until 1835, when the building that was to become the definitive one was built, thanks to the patronage of Don Manuel Munárriz.

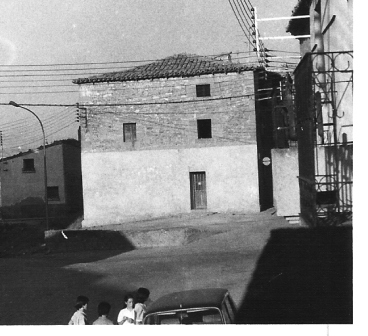

House of the Santo Hospital before its demolition.

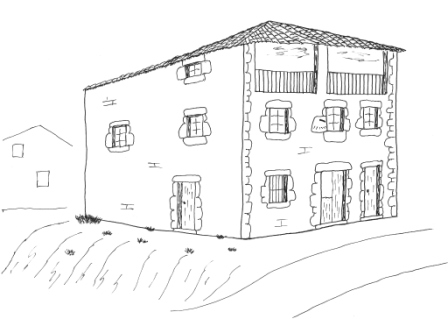

Photograph and drawing by the author

Don Manuel Munárriz, the patron

The Munárriz were an industrious family settled in Mélida since the 17th century and owners of an extensive patrimony, so that for several generations they were the wealthiest family in the town. Manuel was born in 1748 and, at his father's side, he learned to manage the family estate. At the age of 29 he married Josefa Lahuerta, a young woman from Cadreita. They had two children who died when they were still children, so he had a nephew whom he raised and educated as his own son.

Due to various circumstances, he inherited the entire family estate, to which he added that of his wife. In addition, he was an enterprising man and a skillful businessman, knowing how to manage to his advantage the so-called Crisis of the Ancien Régime. Undoubtedly, the worst of the crisis came during the bloody war of Independence, when the contributions of the French and the requisitions of the armies and guerrillas led to the ruin of neighbors, monasteries and municipalities, being the region of La Oliva one of the most punished. As a fisherman in the troubled river of that time, Munárriz increased his patrimony buying cattle, lands -including two corralizas that the town of Mélida had to sell to face the payment of its contributions-, mills, wine cellars, olive presses, etc.

Like many other characters of the time, to the economic triumph he wanted to add the social ascent, and for it, nothing better than the acquisition of a degree scroll of nobility. In 1817, after a long process in the courts, he obtained a favorable sentence on the recognition of nobility, which allowed him to fix the coat of arms of his surname on the front of his ancestral home, which years before he had had built. The house and coat of arms are still preserved in Príncipe de Mélida Street.

However, Munárriz would not enjoy his degree scroll of nobility for long. In July 1820, at the age of 72, he died of "bodily illness". Months later, on the night of January 3, 1821, a party of Aragonese outlaws crossed the Bardenas and attacked his house. After torturing the widow, Doña Josefa, so that she would tell them where she kept the money, the assailants fled with little loot. The woman died days later from her wounds and the thieves were later arrested, tried and convicted. The three ringleaders were hanged.

The hospital building

Upon the death of both spouses and later their godson without direct descendants, the large estate they had accumulated was divided, at the express wish of Don Manuel, into six equal parts, one for the Holy Hospital of the town and the remaining parts for five second nieces. With the inheritance received, the charitable institution decided to build a new hospital building, the cost of which amounted to 6,400 reales de vellón. It was built near the church, at the beginning of the road to La Oliva, and was one of the first constructions to be built outside the old town, initiating the great urban expansion that the town was to experience in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The hospital house was a building Exempt with three floors. The lower floor housed the stables and barns, the first floor housed the sick, and the upper floor was the hospitaler's living quarters. The main façade faced south. A huge ashlar stone that formed part of one of the jambs of the central window was transformed into a sundial. On its surface the hour signs were engraved with Arabic numerals.

Sundial and its location in the new park

Sundial and its location in the new park

It is surprising that this sundial was built when, since the 17th century, a mechanical clock with weights had been in operation, which the council and the church had had placed at the top of the parish tower. In any case, the sundial had an ephemeral life. In 1861 the new Town Hall was built in front of the Hospital, casting its shadow on the façade and rendering the sundial useless. Perhaps it was but a harbinger of what would end up happening to the hospital itself.

The development of a public and universal health system in the middle of the 20th century made the Santo Hospital obsolete. After the death of the last hospitalier in 1953, the building was put to various municipal uses. The progressive deterioration of the building prompted the City Council to order its demolition in 1987, opening a small place in front of the Town Hall and preserving a fragment of the original wall as a silent witness of its existence.

The carved stone of the jamb with the sundial was also set aside and kept. The same one that this spring has been rebuilt and placed in the park located at the end of the road, now a street, of La Oliva, and where almost one hundred years later it marks the time again. That's right, solar time.

bibliography

-GARDE GARDE, J.M., "La beneficencia rural en Navarra (siglos XIX y XX): el Santo Hospital de la villa de Mélida", Sancho el Sabio: revista de cultura e research vasca, 26, 2007, pp. 51-94.

-GARDE GARDE, J.M., "Hidalgos y escudos heráldicos en la villa de Mélida (Navarra)", Revista del Centro de programs of study Merindad de Tudela, 22, 2014, pp. 7-38.