The piece of the month of April 2017

PHOTOGRAPH OF THE FLAG ROOM OF THE LOREDAN PALACE

Ignacio Miguéliz Valcarlos

Museum of the University of Navarra

"To my son I give the royal standard of my grandfather Charles V and the glorious flags that I myself saved, taking them to a foreign land, so that one day, triumphant and beautiful, they may wave again under the wind of my beloved country. These relics I do not give them to you as trophies of war, but as a symbol of my unwavering fidelity and abnegation, and as a testimony of our brilliant past and our beautiful future.... I command my son, after the death of my dear wife, Doña María Berta, and sole guardian of these flags while he lives, to take possession of them and to consider them the greatest treasure of his inheritance". With these words Charles VII bequeathed to his son James III the contents of the Flag Room of the Loredan Palace, his residency program in exile in Venice. Trophies that, as he himself pointed out, constituted the testimony of the inheritance received and of the struggle of the Carlist ideals.

The one who speaks this way is Carlos de Borbón y Austria Este (1848-1909), Carlist pretender to the Spanish throne under the name of Carlos VII. He was the son of Juan III (1822-1887) and Archduchess Maria Beatriz of Austria East (1824-1906), who belonged to the Modena branch of the Austrian imperial house. The marriage had different characters, while Don Juan was of liberal thought, Doña Maria Beatriz was of conservative political ideas and deep-rooted religious beliefs, for which they ended up separating in 1853. After the death of Charles V (1788-1855), and due to the mentality of John III, his stepmother Maria Teresa de Braganza (1793-1874), Princess of Beira, second wife of Charles V and one of the main supporters of the Carlist cause, promoted the candidacy of Charles VII. In 1864 she published a manifesto, Carta de la princesa de Beira a los españoles, in which she recognized Charles as the legitimate heir to his father. Finally, John III abdicated in 1868 the rights to the crown in his son, adopting the degree scroll of Count of Montizón and establishing his residency program in London. In that city he formed a new family with Helen Sarah Carter (1837-1911), from whom he had two children, John (1861-1929) and Helen (1859-1947) Montfort.

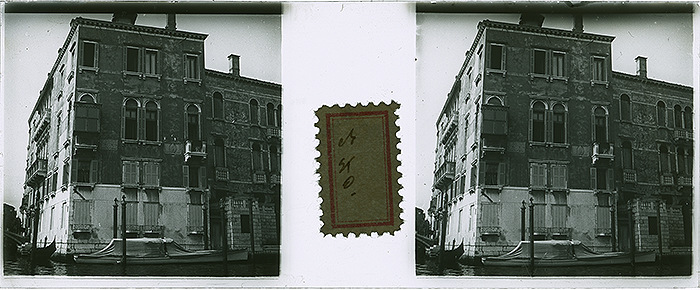

Meanwhile, Charles VII and his brother Alfonso, the future Alfonso Charles I (1849-1936), settled in Modena with his mother, under the protection of his maternal family, moving in 1853 to Prague and in 1863 to Venice, where his uncles, the Counts of Chambord, resided. In 1867 Charles married Princess Margaret of Bourbon-Parma (1847-1893), who actively supported her husband's aspirations. The marriage produced five children, James, future James III, and the infantas Blanca, mother of the pretender Charles VIII, Elvira, Beatriz and Alicia. When his father abdicated in 1868, he assumed the condition of Carlist heir to the Spanish throne, and after the revolution in Spain that expelled Isabel II, he developed an active politics with the intention of recovering the throne. During the third Carlist War (1872-1876) Don Carlos entered Spain, establishing his court in Estella, while Doña Margarita settled in Pau, from where she supported her husband's activity and organized La Caridad, a charitable institution that took charge of the administration of several hospitals in northern Spain. This earned her the admiration and affection of the Carlists, and from then on the women of this movement were known as Margaritas. After the defeat in the war, Don Carlos left for exile definitively, settling in Paris between 1876 and 1881, where the defeated Isabel II also resided, with whom the pretender established contacts tending to the reunification of the two branches. During this time the relationship between Don Carlos and Margarita deteriorated, partly due to the continuous infidelities of the pretender, which also favored attacks from the anti-Carlist press. From 1882, Don Carlos established his residency program in the Loredán palace in Venice, which had been ceded to him by his mother, who in turn had inherited it from her sister, the Countess of Chambord. While Doña Margarita, with her children, did the same in the Tenuta Reale of Viareggio, in Lucca, which she had received from her grandmother, Maria Teresa of Savoy.

In 1893 Doña Margarita died and a year later her widower married Princess María Berta de Rohan (1868-1945). Doña Berta was always accused of being the cause of the distancing of Don Carlos with his children and with the Carlists, as well as of hindering the possible dynastic marriage of the heir, and of destroying documents and belongings of her husband. After his death in July 1909, the Princess of Rohan inherited the palace of Loredán and all its contents, except the so-called Cuarto de Banderas, which was bequest by Carlos VII to his son and successor, Jaime III, leaving the princess as usufructuary and guardian of it. The Cuarto de Banderas was a room in which Charles VII gathered the historical memories of Carlism that he had taken with him into exile. As its name indicates, the flags and pennants that the pretender and his ancestors had used in the Carlist wars, as well as others sent by his supporters, were kept there. Other objects related to the Carlist wars and tradition, such as berets, medals, different weapons, seals, saddles, paintings and drawings, sashes and decorations, were also kept there. The setbacks of the First World War and the bad administration of the princess made that Mrs. Berta was in economic difficulties, having to sell the palace and its contents to the film actress Francesca Bertini. In 1925 her brother-in-law, Alfonso, before the possible trip of Don Elio Elío y Magallón (1852-1938) Marquis of Vessolla to Venice, told her that "Berta lives there like a beggar, she goes from one hotel to the next without paying the bill. We were told that there is a very charitable American gentleman there who helps many people and her too". Among the objects that the Princess was obliged to sell were those of the Cuarto de Banderas, which she only kept as a guardian. Again it is Don Alfonso Carlos who in March of 1928 tells the Marquis de Vessolla what happened with the pieces conserved in that room "What happened to the Flags of Loredán's Flag Room was as follows. As M. Berta has many debts in Venice, she allowed them to take the objects of which Charles left her a depository and guard while he was alive, and which were pawned as a guarantee for the creditors. We were warned on two sides to see if we could prevent them from being lost. One of those who warned me was the antique dealer Gio Carrer that you know and that we saw in Vienna. He told me they were deposited at ...... (sic) and that they were said to be sold at auction. Later he wrote to me that the auction had been suspended due to someone's intervention. From Beatriz we learned lately that it was the Marquise de Villalba who rescued them and returned them to María Berta. She should have given them to Jaime as owner of the flags, etc. Perhaps that M. Berta continues to speculate with them. Nice guard!". After this first failed attempt, finally the Princess of Rohan was able to sell the flags, apparently to some antique dealers in Paris, from whom they were bought by a millionaire named Middleton, who donated them to the Baleztena family. Joaquín Baleztena Ascárate gave these pieces to the Museum of Historical Memories installed in the seminar of San Juan Bautista of Pamplona, and after the Pamplona City Council dismantled this space they passed to the Museum of Tabar and from there to the Museum of Carlism of Estella.

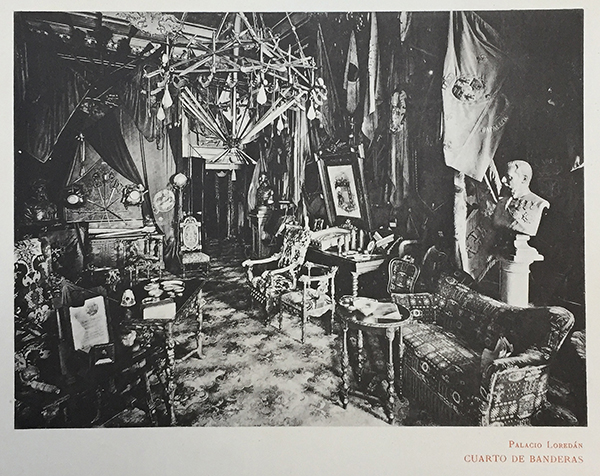

The Flag Room of the palace of Loredán was reproduced by the Carlist press on two occasions. In December 1890 El Estandarte Real announced the publication of four zincographs, one for each wall canvas of that room, made by the draftsman Paciano Ross and the lithographer Victor Labielle according to the model given by the painter Luigi Gasparini. These chromos, as the publication called them, were published in the issues of December 1890 and January, May and June 1891. In them the different objects exhibited in the estancia were shown in detail, accompanied by comments on them by Francisco Melgar, Don Carlos's secretary. Years later, in 1907, Fomento de la Prensa Tradicionalista de Barcelona published an album on the Loredán palace, Los Duques de Madrid en el palacio Loredán, in which twenty-two plates showed the main rooms of the palace, as well as Don Carlos accompanied by Doña Berta. These images were accompanied by eighteen texts that in poetic tone narrated the history of Carlos VII, of the Loredan palace and its rooms and of the Carlist efforts. As it could not be otherwise, the Cuarto de Banderas was also included, accompanied by a text written by the Carlist army general Emilio Martínez Vallejos in the same epic prose as the rest of the publication.

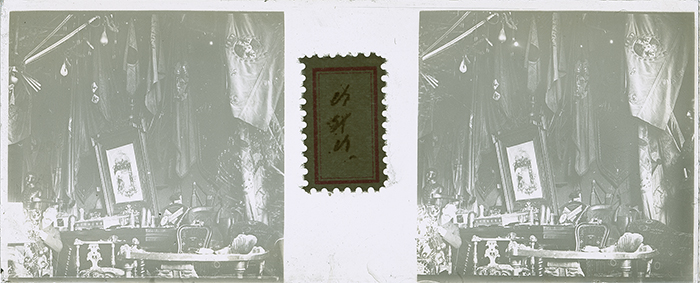

Room of Flags. Loredan Palace (Venice). 1909

Private collection. Pamplona

Two years later, in 1909, during a boat trip through the Mediterranean whose final stop was Venice, one of the travelers took a series of photographs of the city, including a snapshot of the Cuarto de Banderas. Thanks to this image, preserved in a private collection in Pamplona, we can see the hall as it was in June 1909, a month before the death of Charles VII. Thanks to these three photographs we can see how this room remained unchanged throughout the years, with the same layout not only in terms of the historical objects preserved in it, but even in the complementary furniture. The three are centered on the canvas of Honor of the room, in which the most emblematic elements were arranged, and which is described by Francisco Melgar in El Estandarte Real in December 1890: "In the center, below the laurel wreath that encloses the motto Dios, Patria, Rey, is the banner of the Generalísima, embroidered by H. M. the Queen María Francisca, and that accompanied Carlos V and Carlos VII in their campaigns. To the right and left, Carlist lances and historical berets. To the right of the viewer, the flag of the Royal Corps of King's Guides. To the left, the flag of the Battalion Cazadores del Cid, 1st Battalion of Castile. Above both, two of the flags with which the movement began in the North in 1872. Below the banner of the Generalissima, trophy of swords, in a semicircle: among them, of the three Carlos, the Infante Don Fernando, the Marquis of Valde-Espina, Ollo, Elío, Lizárraga, Rada and other general officers; staffs and sashes of Kings and Generals. Below, the parchment of Gasparini in honor of the main Carlist leaders killed in campaign. On the table below, collection of projectiles made in the Carlist factories; in the center, wax from the blandones that burned in the catafalque of Charles V; at one end, General Ortega's cross of San Fernando; at the opposite end, flowers from Portugalete. - Continues to the right of the viewer: pennants of the 1st, 2nd, 4th and 6th Companies of the 1st of Navarre, attached with a bomb, model of those dropped on Bilbao. Below, bronze shield with the names of the acts of arms attended in person by Charles VII. Below, the last saddle of Charles V in the Seven Years' War. On the right: flag of the 4th Battalion of Crusaders of Castile, in the form of a banner; below, the flags of the Guides of Castile and the Hunters of Palencia, 5th of Castile. Below, the flags of the 8th of Guipuzcoa and of the Cazadores de Tolosa, 3rd of Guipuzcoa. Below, the wooden box in which the banner of the Generalissima was enclosed from the war of Charles V to that of Charles VII. To the left of the viewer, starting from the central trophy: four pennants of the 2nd, 5th, 7th and 8th Companies of the 1st of Navarre, held by a model of the largest Witworth projectile used by the Carlist artillery. Below, bronze shield with the names of the general officers of both armies killed in the war from 1872 to 1876. Below, Queen Maria Teresa's campaign chair. - Further to the right: the flag of the 1st of Gerona, in the form of a banner. Below, the flags of the Marquina Battalion, 3rd of Biscay, and the Infanta Doña Elvira Battalion, 5th of Navarre. Below, the flag of the 4th of Alava and the flag that served for the uprising in La Rioja in 1872. Above the latter group of flags, the bust, in steel, of Charles VI" Thus, in the photograph studied here, the flags hanging on the walls can be seen, together with panoplies and banners, as well as the decorative variegation, with a profusion of furniture and objects. Among the pieces that can be recognized without difficulty are in the center of the image the flag called Generalísima, embroidered by Doña María Francisca de Braganza, wife of Carlos V, in 1833, framed to the right and left by the flag of the Royal Corps of King's Guides and that of the Battalion of Cid's Hunters. Under these flags there is a framework with a parchment made by the painter Luigi Gasparini in honor of the main Carlist leaders fallen in the battles, and behind it stand out the grips of a wheel of swords, weapons that had been owned by Charles V, Charles VI, Charles VII, the Infante Don Fernando, the Marquis of Valde Espina, and the generals Elío, Ollo, Lizarraga and Rada. There are also two bronze coats of arms, one of them inscribed with the names of the battles that Carlos VII attended, and the other with the names of the generals killed in the second Carlist War (1872-1876). The saddle of Charles V and the steel bust of his son, Charles VI, are also recognized.

Banderas' room in The Dukes of Madrid at the Loredan Palace (Venice). 1907

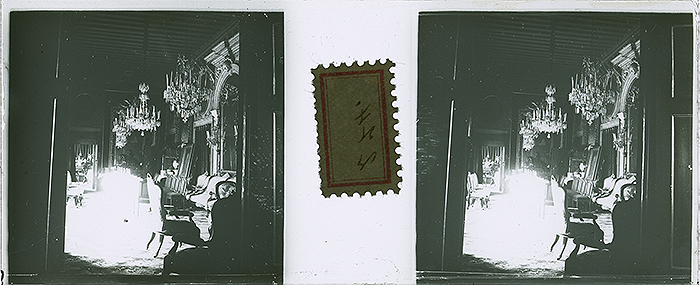

Six other photographs of Venice are part of the same report as the previous image, two of them linked to the Carlist tradition, a general exterior view of the Loredan palace, and an interior view of the Hall of Honor, very similar to two of those published by Fomento de la Prensa Tradicionalista de Barcelona in 1907. And next to them four views considered as tourist: three perspectives of the Grand Canal, the Rialto Bridge and the place of San Marco and an image of the Doge's Palace. Both the snapshots of the Flag Room and the Hall of Honor of the palace are photographs that reflect the difficulty of photographing interiors with amateur cameras, as the first is overexposed and the second underexposed. While the rest of the images show general views with open angles that give amplitude to the snapshots and show tourist images of the city, or present a monument in the foreground, occupying the entire spot. Despite the small size of the plates, the images are of extraordinary sharpness, capturing all the details in detail, which makes it possible that in case of enlargement, no detail would be lost. This is important because these plates, in addition to being viewed with stereoscopic viewers, could also be projected by means of light, like a slide. This second possibility summarizes the use that was given to these images, since in the boat trips during the voyage, and as a form of entertainment, the photographs taken by the members of group were projected.

Loredan Palace (Venice). 1909

Private collection. Pamplona

Salon Palazzo Loredan (Venice). 1909

Private collection. Pamplona

These are photographs in stereoscopic format of gelatin (silver bromide) on glass plate of uniform format, horizontal projection, and with a size of 4.5 x .7 cm in the primary support, and 4.1 x .2 cm each of the spots. This subject of plates already prepared with gelatin-bromide emulsions could be used long after their manufacture thanks to their good preservation conditions, which also allowed advances in their commercialization. Stereoscopic photography allowed the capture of an image in three dimensions, very similar to how the human eye would see it. For this purpose, a binocular camera was used, which had two lenses with the same focal length, thanks to which two very similar images were obtained, with a slight deviation of the visual axis. When looking at the two resulting shots at a certain distance and with the appropriate viewfinders, the human eye saw them at the same time, superimposing one shot on the other, which gave the sensation of seeing it in three dimensions. The evolution and development of this technique went hand in hand with that of photography itself, since the first attempts were made with the visualization of drawings on paper and cardboard, later with the creation of Brewster's binocular machine, and above all with the strong impulse of the London exhibition of 1851. Its great diffusion took place from 1855, largely due to the use of collodion as a base for the glass negative and albumen for the printing on paper, and on the other hand by the consolidation of large commercial houses. An important milestone in stereoscopic photography was the invention by Jules Richard of a new system for capturing these images, with the employment 4.5 x .7 cm glass plates that were printed by contact on glass plates of the same dimensions, but inverting the images from right to left. This system, which consisted of a camera, the Vérascope, as well as an assortment of viewfinders and accessories, was very versatile and small in size, which made it particularly practical for travel and excursions.

These plates were manufactured by the Ilford company, business dedicated to the manufacture of photographic material, still in existence today, specializing in black and white photography. It was created in 1879 by Alfred Hugh Harmand (1841-1913), a pioneer of photography, who began manufacturing bromide gelatin plates at his home in Ilford, near London. Thanks to the growing demand for photographic material, Harmand was able to expand the business in 1891, renaming it Britannia Works, having to be relaunched in 1898 as The Britannia Works Company and finally in 1900 under the name of Ilford Limited. All the boxes retain on the front and sides the label of the house, which also gives instructions on how to develop or develop the plates.

We know nothing about the author of the photographs studied here, since there is no record of the name or signature in any of the images, and also the family that owns the collection does not know the authorship of them. In relation to this we propose three different hypotheses. The first one is that the author is a photographer hired by the board organizer of the trip to make a report of it. In this sense, in a similar trip held in 1905, it was stated that "The organizing board will also take an artistic correspondent, with whose help, at the end of the trip, an interesting chronicle of the trip and a complete album of views of all the countries and places visited can be published". The second hypothesis suggests that they were the work of one of the participants in the trip, which would be made possible by technical innovations in the photographic world. The creation of dry gelatin-bromide plates, the advances in photographic machines and the production and commercialization of all the material necessary to develop and print photographs, both on paper and glass, allowed the expansion of photography and the emergence of amateur photographers. Thanks to this, many of the participants in the trip carried their own cameras, as indicated in one of the chronicles of the trip: "Meanwhile the photographers, whose issue is legion, roam the deck like hunters in a hunting ground, lavishing shots left and right...". Finally, the third hypothesis that arises is that this report is actually the work of several photographers, who at a certain point in the trip pooled the photographs taken by them to be viewed during the boat trips, as had happened on a previous trip "Finally, after dark, some projections were made of photographs taken by several travelers in the course of the trip ...". In either case, making copies of these images was no problem thanks to the invention of the new system of copying stereoscopic images by Jules Richard.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Del Burgo, J., Carlos VII y su tiempo, Gobierno de Navarra, Pamplona, 1994.

El Estandarte Real, October 1889, nº 7, p. 102.

El Estandarte Real, December 1889, nº 9, p. 143.

El Estandarte Real, January 1890, no. 10, pp. 152 and 158-159.

The Royal Standard, February 1890, no. 11, p. 176.

The Royal Standard, March 1890, no. 12, pp. 190-191.

The Royal Standard, May 1890, no. 14, pp. 222-223.

The Royal Standard, June 1890, no. 15, p. 239.

The Royal Standard, July 1890, no. 16, p. 255.

The Royal Standard, August 1890, no. 17, pp. 270-271.

The Royal Standard, September 1890, no. 18, pp. 287-288.

The Royal Standard, December 1890, no. 21, pp. 333-335.

The Royal Standard, January 1891, no. 22, p. 16.

The Royal Standard, May 1891, no. 26, p. 79.

El Estandarte Real, June 1891, no. 27, p. 94.

FERNÁNDEZ RIVERO, J.A., La imagen estereoscópica. Three dimensions in the history of photography, Málaga, Miramar, 2004.

LAVEDRINE, B., Recognizing and preserving old photographs, Paris, committee des Travaux Historique, 2009.

MELGAR, F.M., Veinte años con Don Carlos. Memoirs of his Secretary the Count of Melgar, Madrid, Espasa-Calpe, 1940.

MESTRE I VERGÉ, J., Identificación y conservación de fotografías, Gijón, Trea, 2004.

MIGUÉLIZ VALCARLOS, I., Cartas de don Alfonso Carlos de Borbón y Austria Este al marqués de Vessolla. Una mirada íntima al día a día a día del pretendiente carlista, Pamplona, Gobierno de Navarra, 2016.

Museo de Recuerdos Históricos. Catalog de banderas, Pamplona, 1942.

POLO Y PEYROLÓN, M. D. Carlos de Borbón y de Austria-Este. His life, his character and his death, Valencia, Tipografía moderna, 1909.

PRUNÉS PUJOL, F., Catalonia at War, 1872-1876. Biografía de un heroico soldado de Carlos VII: Pablo Jacas Dalmau, Madrid, conference proceedings, 2002.

SANTA CRUZ, M., Apuntes y Documentos para la Historia del Tradicionalismo Español 1939-1966, Madrid, Gráficas Gonther, 1979.

URQUIJO, J., La Cruz de Sangre. El Cura Santa Cruz. Pequeña rectificación histórica, San Sebastián, Nueva publishing house, 1928.

VV.AA., Los señores duques de Madrid en el palacio Loredán, Barcelona, Fomento de la prensa tradicionalista, 1907.

VV.AA., Reyes sin trono. Los pretendientes carlistas de 1833 a 1936, Pamplona, Gobierno de Navarra, 2013.