The piece of the month of August 2017

PHOTOGRAPHY AND RESTORATION: THE CLOISTER OF THE CATHEDRAL OF TUDELA IN 1932

Pilar Andueza Unanua

Chair of Navarrese Heritage and Art

Photography as a historical document

There is no doubt that photography as historical-artistic heritage participates in the duality inherent to works of art: it possesses aesthetic qualities, which allow human enjoyment and fruition, and historical values that, as Alois Riegl indicated when referring to the monument, make it a link in the material history of man. However, photography is not only a technique, an artistic object or a testimony of its time, like any other artistic manifestation. Sometimes, as in the case of this specimen, photography, in addition to offering multiple values and functions, becomes a crucial documentary source , a visual record of the first magnitude taken at a certain time, which is essential for the study of historical-artistic heritage and the implementation of any conservation and restoration intervention. Sometimes, the sources that have reached our days are exclusively textual. However, photographs, as graphic documents, acquire an extraordinary utilitarian value by becoming iconographic documents, essential tools for the deep knowledge of a monument, its history, its transformations, the additions or deletions of strata or the interventions that have taken place. And so it happens with this photograph of the cloister of the cathedral of Tudela. Logically, the information offered has to be analyzed and deciphered, but the authenticity of its content comes to fill in to other historical sources and can provide firsts, new information and even unique data , which otherwise would be impossible to obtain. In short, as stated in article 49 of Law 16/1985, of June 25, 1985, of the Spanish Historical Heritage, the photograph can be considered without a doubt a document, defining it as "any expression in natural or conventional language and any other graphic, sound or image expression, collected in any material support subject , including computer media".

A photograph of the cloister of the cathedral of Tudela in 1932.

The photograph now presented, kept in the Bildarchiv Foto Marburg, is dated 1932, as indicated in the file that accompanies it on its website. It measures 13 x cm and its author is unknown.

Photo 1. The cloister of the cathedral of Tudela in 1932.

(Photo: Bildarchiv Foto Marburg)

sample the north and west bays of the cloister of the cathedral of Tudela before the restorations carried out from 1941 onwards by the Institución Príncipe de Viana. And it is precisely its chronology, immediately prior to these interventions, which gives it a great documentary value as it is an indispensable source for the study of Tudela's immovable heritage, as it testifies to the state of conservation of the cloister space before its restoration. Comparing it with other later photographs, it provides data fundamental to know the evolution of the current building and allows us to fill in what other documents collect. It undoubtedly provides much more precise information than an engraving, a painting or a drawing, whose images are always filtered by the subjectivity of the artist.

The cloister of the cathedral of Tudela

When Tudela was conquered by Alfonso the Battler in 1119, its cathedral dedicated to Santa María was erected as a collegiate church over the city's main mosque, following a very common practice in the Hispanic reconquest internship . Inhabited and governed by a community of canons that followed the rule of St. Augustine, a cloister and outbuildings had to be built next to the church, works that were basically carried out in the last third of the 12th century in Romanesque style.

The cloister, formed by four bays, follows a quadrangular structure, with slightly longer east and west sides. The galleries open through a single level with semicircular arches resting on paired or triple columns. Both in the center of each band and in the angles there are pillars to which are attached capitals in issue of two and four respectively. These capitals present both vegetal and figurative motifs typical of the late Hispanic Romanesque style.

Over time the cloister underwent important transformations with architectural additions that undoubtedly modified its original appearance. As can be seen in this photograph, the original stone arches were covered and, over them, three large pointed and semicircular arches on each side were erected in brick, separated by buttresses. On the interior, the work was masked by a brick ribbed vault. On this lower level, a second floor was built, opened by lowered arches on the east side and by large linteled openings on the west. All of them in turn were closed at an undetermined time and pierced by linteled windows at some later time. On the north side a third level was still built as a sill. The same was not done on the west side, where the geometric play of the brick corresponding to the eaves of the Dean's Palace can be seen.

The restoration of the cloister in the 1940's.

On December 16, 1884 the cathedral of Tudela was declared a National Monument. In this way the building was one of the strongest candidates in the country to receive state funds for its restoration. A year later, the architect Julián Arteaga, at the request of the Monuments Commission of Navarra, made a report on the restoration needs of the building. It was sent to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando, which issued a favorable report to carry out the intervention. In this report, which recommended mainly the repair of the vaults and roofs of the temple, the lamentable state of the cloister -as shown in the photograph- was highlighted, while recognizing the impossibility of restoring it at the same time as the temple due to its very high cost:

"The accidents of this nature - he refers to additions to the building - are reduced to constructions executed some to establish dependencies for the service of the church, and others to particular constructions attached to the exterior walls that hide the beauties of the factory without destroying it, reducing the damages caused in their majority to simple hollows practiced in smooth walls as it happens with the lateral chapels added to the sides of the primitive factory.

Exceptions are, however, the works carried out with bad committee on the cloister, which is now in a pitiful state.

Built like those of its time with narrow arcades supported by weak columns arranged two by two and three by three, designed to support a relatively small weight of vaults, huge walls have been built on these arcades that rise up to twelve or fourteen meters at some points and that support several floors, some serving as dependencies to the church and others to the bishop's palace.

As a consequence of this, the base not being able to withstand such enormous loads, the columns have been dislocated and the walls have affected a collapse poorly contained with huge buttresses of brickwork, being found by this same cause partitioned all the arches, cracked the primitive vaults of the cloister and destroyed many details of the decoration.

I do not think it is appropriate nor do I understand that it is from this place to propose the works of repair and restoration of the cloister, it would require a huge budget , exceeding the available resources".

After the Commission followed all the steps recommended by the secretary of the Academy, in 1887 the required financial aid was obtained for the restoration, which, focused on the roofs of the church, was executed until 1888, although in the following years work was still carried out on the roofs.

The cloister of the cathedral of Tudela still had to wait several decades for its restoration, which took place in its most significant aspects throughout the forties of the last century. Still in the 21st century, a last direct intervention has been carried out in order to safeguard the monumental sculpture of its capitals, whose stone showed a serious and progressive deterioration.

As can be seen if we compare the photograph presented here with current photographs, the restoration carried out after 1941 was of great importance, completely transforming the state in which that space had remained for several centuries. As Dr. Mercedes Mutiloa has documented in detail, the recently created Institución Príncipe de Viana began the procedures for the intervention in March 1941, focusing all its efforts on this work and on the palace of Olite under the direction of the architect José Yárnoz Larrosa, with José María Lacarra as secretary at the time. In the summer of that year, the demolition of the upper floors and the dismantling of the cloister galleries began, as there were doubts about their stability and stability. During the following years, the foundations and reconstruction of the arches were laid and the interior perimeter walls were consolidated. Once the reconstruction of the arches was completed in 1944, it was intended to cover the structure with wood the following year, but the scarcity of the material forced the postponement of this task until 1948, when it was finally carried out.

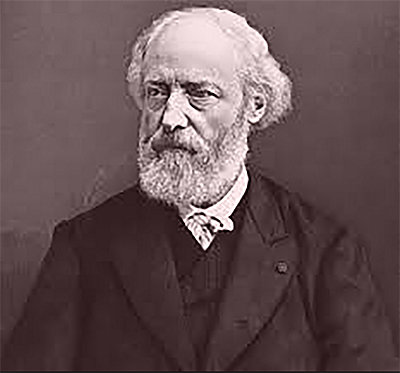

Photo 2. José Yárnoz Larrosa

(Photo: file General. University of Navarra)

Restoration criteria

An analysis of the works carried out allows us to verify that this restoration did not strictly follow the positions of any specific restoration trend, but rather the intervention was individualized, from agreement with the pathologies suffered by the building. In this sense, this restoration is linked to criteria corresponding to the different ideas developed between the second half of the nineteenth century, such as stylistic restoration, and the first half of the twentieth century, such as scientific restoration, even coinciding in some aspects with later approaches linked to critical restoration and even the culture of maintenance, typical of the second half of the twentieth century and our days.

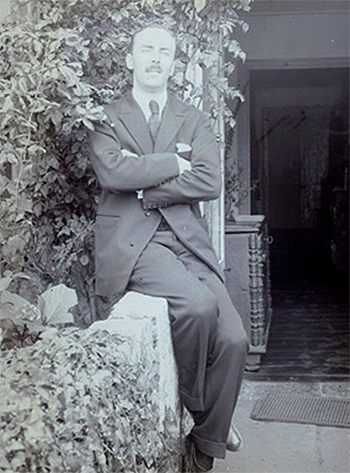

After the Spanish Civil War and for several decades, monumental restoration in Spain was based, in general, on criteria far removed from the international thesis and linked to nineteenth-century criteria, very outdated by then. The conservative thesis of Torres Balbás, who had drawn from scientific restoration and the Athens Charter (1931), applied during the Second Republic, were generally banished and positions linked to the stylistic restoration of Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879), or the historical restoration of Luca Beltrami (1854-1933) were recovered. In fact, related to Romanticism, the restoration in style was born in France by Viollet-le-Duc, who compiled for the first time in a systematic and coherent way a theory of architectural restoration that he endorsed with his interventions in outstanding monuments of the French heritage. With his position ("to restore a building is not to maintain it, repair it or remake it. It is to restore it to a Degree of integrity that may never have existed"), he not only sought to recover the original state of the building, but he also endorsed the possibility of giving the building an ideal form that it may never have had under the pretext of the unity of style and the ideal state of the monument. In this way he not only justified the elimination of strata, but also the possibility of fill in an unfinished work, reconstructions and additions, based on typological and stylistic analogies. The great reputation and prestige of the French architect meant that his theory was very popular in Spanish monumental restoration. It was not only applied in the 19th century, with Demetrio de los Ríos as its maximum exponent in the cathedral of León, but also in the first third of the following century and even during the Franco era. In this sense, the restoration of the cloister of the cathedral of Tudela, trying to restore refund the cloister to its primitive aspect, demolishing the non-original parts, although with several centuries of history, including the ribbed vaults, and dismantling absolutely all the galleries to rebuild them again, is linked to the echoes of this theory.

The condemnation of the Violletian thesis did not take long to arrive in the 19th century, accusing them of falsifying the monument, both in terms of the adulteration of the subject, as well as their intention to pass off as ancient and original reconstructed or reintegrated parts. From England, from the hand of another Romantic, John Ruskin (1819-1900), a strong civil service examination arose, with a fatalistic doctrine that advocated non-intervention and absolute respect for the work of art, destined to disappear due to the inexorable passage of time, although it defended preventive conservation. The criticisms of Ruskin and his followers, as well as the excesses and adulterations produced by Viollet's epigones led to the birth in Italy of the historical restoration or historical-analytical method. It emerged as a rectification of the stylistic restoration. It did not renounce reconstructing or finishing incomplete buildings, but in theory it avoided hypothetical and idealistic reconstructions by trying to respect the veracity of historical documentation (archaeology, engravings, paintings, photography, etc.).

Photo 3. Viollet-le-Duc

The Athens Charter (1931) headed by the Italian Gustavo Giovannoni proclaimed new principles of restoration: scientific restoration, whose instructions had already been established by Camillo Boito in 1883. Thus a third way was chosen, halfway between Viollet and Ruskin, condemning the arbitrary excesses of restoration in style and moving away from Ruskin's fatality to defend an intermediate position that admitted restoration, but excluding forgeries and evidencing additions, all this for the sake of defending the monument as a document and therefore under a staunch defense of authenticity, thus prevailing the historical written request , respecting the transformations experienced by the monument throughout history and opposing the recreated unity of the monument. Although a priori it might seem that the restoration carried out by Yárnoz Larrosa in Tudela was far from these positions, the consolidation of the interior walls of the cloister, as well as the addition of new capitals of cubic appearance and without sculpture in those places where the original Romanesque capitals had been lost, in order to harmonize the whole without falsifying the arches, link this intervention in Tudela to the scientific restoration. We also know that the leading exponent of this trend in Spain, Leopoldo Torres Balbas, visited the Tudela cathedral in 1946 at the request of the then secretary of the Institución Príncipe de Viana, José Esteban Uranga, to carry out a report on the cathedral and its cloister, although it is interesting to note that his opinion was published at apply for well into the restoration process.

Photo 4. Leopoldo Torres Balbás

(Photo: board of trustees de la Alhambra y Generalife)

The destruction of a large part of the European historical-artistic heritage during World War II made the "restauro scientifico" difficult to apply in the face of the psychological need to recover the historical report through the monuments. Many buildings were rebuilt and reintegrated, without highlighting the additions, as Giovannoni had advocated in the past, so that the historical or documentary value of the monument was losing ground to its artistic value, in a long struggle that continues to this day. It was in this context that a new current of restoration began to emerge, which defended the artistic value over its historical value, advocating the recovery of the figurative unity of the work of art for the transmission of its expressive values and whose principles were embodied in the Charter of Venice of 1964 and in the Charter of the Restoration of 1972. The elimination of strata was justified, always in an exceptional way, if the aim was to recover the potential unity of the work of art and facilitate its reading, so in this sense the restoration carried out in Tudela participated in this same spirit, since there is no doubt that the Tudela cloister had lost its aesthetic capacity with the additions.

From the 1960s and 1970s to the present day, new currents of restoration have developed. This is the case of integral conservation or pan-conservationism, born from the hand of framework Dezzi Bardschi who returned to put the emphasis on the historical written request , rejecting the restoration to depend on the critical judgment -always subjective- of the restorer, and advocating preventive conservation. Finally, the 1987 Carta del Restauro (Restoration Charter) took up the so-called culture of maintenance, led by Paolo Marconi, aimed at the conservation or restitution of the expressiveness and cultural meaning of the work of art, even if this meant sacrificing the material authenticity of the work of art, to which he downplayed its relevance, criticizing the differentiation of materials and the excessive importance given to historical value, and defending the use of traditional materials and techniques.

Photo 5. Cloister of the cathedral of Tudela at present.

(Photo: Friends of the Cathedral of Tudela)

In light of this 1932 photograph and the restoration work carried out in this cloister with the elimination of various strata, as well as the dismantling and subsequent reconstruction of the arches, it is worth asking in the always controversial task of restoration: are we facing a false historiography, what role does authenticity play in a monument, should the documentary and historical value take precedence or should the aesthetic and cultural value of the work of art prevail, have old restorations led to false historiographies, have old restorations led to false historiographies, and if so, what is the role of authenticity?

bibliography

-GONZÁLEZ VARAS, I., Conservación de bienes culturales. Teoría, historia, principios y normas, 5th ed., Madrid, Chair, 2006.

-LARA LÓPEZ, E. L., "La fotografía como documento histórico-artístico y etnográfico: una epistemología", Revista de Antropología experimental, 5, 2005.

-MUTILOA ORIA, M., La Institución Príncipe de Viana: creación y política cultural (1940-1948), Pamplona, Government of Navarra (in press).

-QUINTANILLA MARTÍNEZ, "Las intervenciones de la Comisión de Monumentos Históricos y Artísticos en la catedral de Tudela" in La catedral de Tudela, Pamplona, Gobierno de Navarra, 2006, pp. 379-397.