The piece of the month of July 2017

THE BAIGORRI PALACE: THE FIRST PALACE OF THE NEW STYLE

Juan Carlos Valerio Martínez de Muniáin

Architect

Fernando Chueca transmitted us the admiration for that Spanish moment in which the flowery Gothic is heading towards a culmination, which will not be exalted and expressive as in England and Central Europe, but serene and luminous. For Chueca he gave in a synthesis that he will call Elizabethan, Manueline, and, in mixture with the incipient Renaissance, Plateresque.

For foreign historians, who usually know so little about Spanish art, it is a final Gothic, a bastard renaissance. However, this style, which coincides with the culminating period of Spain and Portugal, with the end of the Reconquest, with the intuition of the Empire, when both countries are creating a new vision of man that they will try to impose on the known world, is no longer essentially Gothic, nor is it Renaissance.

In its religious architecture the space is unified, it tends to a simple nave of very clear structure, wide, when the space is of three naves it tends to unify them making the lateral naves subsidiary, as chapels of the central nave, or integrating them in a unique nave with its vaults at the same height, the so called columnar churches.

This unity of space is no longer gothic, neither is the flatness of its vaults, incredible structural boasts, nor is the high, thin and slender light, produced by small holes in the great walls, nor is the rotundity of the exterior, these great ships, where neither the flying buttresses nor the pinnacles are expressed, and, if they can, neither are the abutments.

That austerity, that purity of volumes, could bring us closer to the Renaissance, but it is not so, the Renaissance meant a destruction of the Gothic organism and in it there is a return to the maze of volumes, of cubes united by geometric laws and hierarchies. The Renaissance space begins with great ingenuity, the space of this style of ours is a mature space, it is a longed-for culmination after many centuries of Gothic evolution.

Renaissance architecture will need to articulate its walls with pilasters, with cornices, with orders, they will never dare to make the immense bare walls of our style. Our style needs neither the articulation of the Gothic speech nor the Renaissance orders, it is an architecture born of the interior, of the internal space shown without fear of the exterior. In this aspect its medieval origin is detected, natural, spontaneous, true, not subject to any rules other than the forces of nature, it is not intellectual like the Renaissance.

Our style was not discovered by foreign historians, and even national historians did not know how to classify it as a final Gothic or a protorenacimiento. I think it is clear that one of its disadvantages was that it had no name, in another article I called it "new style" because it was something new, unexpected, unknown, misunderstood. Chueca was on the point of naming it, of giving it surname, because until it does not have it, it will be unknown.

This style created a new spatial conception, which evokes a new world, wide, modern, optimistic, generous, and very serene and spiritual, because in spite of its structural achievements, these do not try to manifest themselves, they remain silent, naturally, when we all know the immense tensions that descend through its serene walls.

Its spaces are spaces of peace, of serenity, with its high light illuminating the vaults, descending through its bare walls, with its isolation from the outside, which does not matter to it, thus separating itself from the Gothic and Renaissance.

Its silence has something of the Hispanic world, which others would say Hispano-Arabic, its air of stopped time brings it closer to the painting and architecture called metaphysical, but this one exaggerates the sensations and our style does not, its air of eternity, of being outside the styles, does not sample, it possesses it without more.

In the decorations of his cornices and capitals he does not mind using gothic themes, soft moldings, flowers or bunches, or reborn angels, but he is somewhat indifferent, he only needs soft lines.

This new style will fill the peninsula with new temples that we recognize immediately by their naked and rounded volumes, their high hollows, their austere abutments, their clear presence in the landscape, and in the interior by their interlaced vaults, very flat, in whose simple and fine ribs, almost decorative, we intuit the real vault that seems to float above them. You will recognize its very spacious interiors, very daring, and that feeling of naturalness, of no effort, despite the wide lights covered with vaults.

In spite of the spectacular nature of their beautiful columnar churches, I believe that their prototype, their essential space, was the church with a single nave, sometimes with Wayside Cross formed by side chapels, insinuating slenderness from the outside, but being really very wide from the inside.

But now I wanted to talk about this style in civil architecture, in palaces, in a single original palace, prototypical, unequaled in Europe, it is the palace that the Count of Lerín, head of the Beethoven side in Navarre, built in his forest of Baigorri, in the region of La Solana, located between the municipalities of Lerín, Larraga, Allo, Dicastillo, and Oteiza.

Photo 1. Baigorri Palace (Photograph: Catalog Monumental de Navarra)

The landscape of Baigorri was a vast oak forest located on the plateau of high plateaus at the end of what was considered Tierra average, which fell in cliffs over the river Ega. From Baigorri onwards, the landscape becomes more desert-like and the so-called Ribera begins.

The location was perfect, isolated, with no nearby villages, to build a pleasure palace following a Gothic tradition expressed in the Renaissance.

But the palace was not just another palace, it will use the language of the tall octagonal columns, here transformed into cylindrical ones, of distant Hispano-Arabic origins, taken up again in the Hispanic Gothic, and which will become part of the Renaissance language, but which for me define the language of this new unclassifiable style.

I have often wondered if this architecture is the civilian version of that new style that appears so clearly in religious architecture. But the Baigorri palace breaks all the canons, it does not respond to the model of the Hispanic, Levantine Gothic palaces, with its asymmetrical patio and its grand staircase as the protagonist of the patio, but neither to the Renaissance patios of arches, nor to the palaces of linteled patios of this new style: Castilian patios, Estellan patios, the patio of the palace of the Condestable, Count of Lerín, in Pamplona.

Its language seems to be the offspring of the latter, high Hispanic linteled courtyards, with that still Gothic verticality of its columns, contrasted with the horizontality of its lintels, a heritage of the Hispano-Arabic world, with that secret violence, without contemplation, which makes them inscribe in this new spirit, in its contrast between the column, the most valuable and decorated piece, and the silent interior and exterior walls.

However, their linteled, architraved character prevents them from reaching the synthesis of the vaulted naves, where the forces go from the sky to the foundations, integrating everything, unifying everything in the structure.

Their architraved character makes them move towards fragmentation, towards the rupture of unity, the scourge of the Renaissance, the rupture of man, of his consciousness, a rupture that the Renaissance was only able to overcome in the Baroque, which will tend again towards unity.

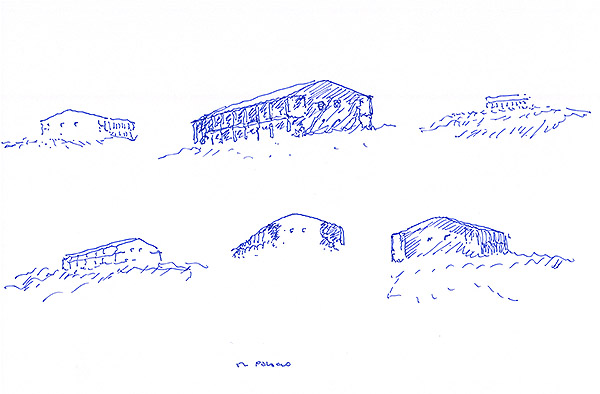

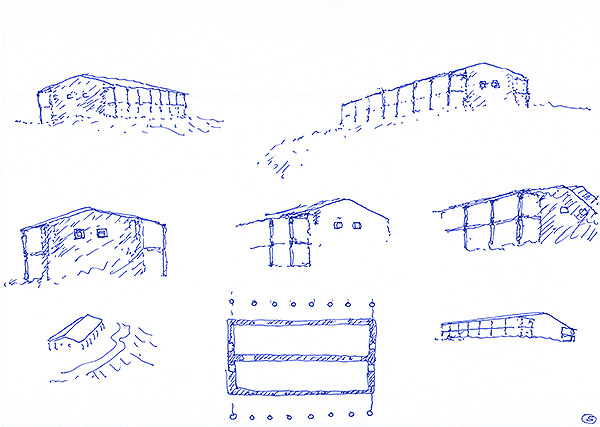

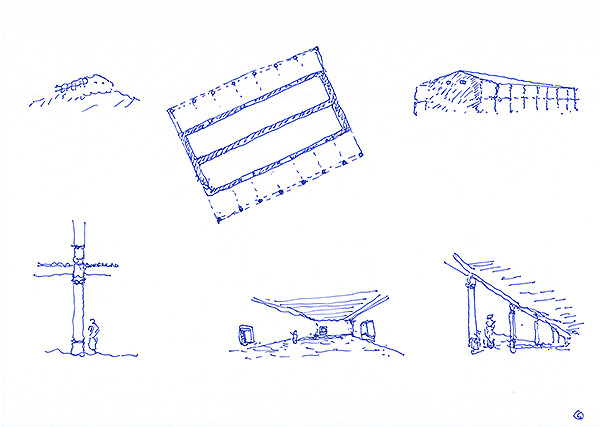

Drawings of the Baigorri Palace, by Juan Carlos Valerio.

This palatial architecture of the New Style can only recover a certain unity if it maintains an intense tension between its elements, between the columns, key pieces of its architecture, and the wall. It achieves this in the courtyards by maintaining very strong walls and vertical courtyards oppressed by them, but the Baigorri palace will try another way.

He is going to try a new, unexpected prototype. First of all Withdrawal to the courtyard, a courtyard that I always considered a wound in the Renaissance, an incomprehensible space in it. In the place of the courtyard, of the void of the cube, he will opt for a full one, in the heart of the building he will place a wall, something unknown until then in architecture.

The wall, blind, painful, points to an atrocious nihilism, there is nothing in the heart of man, only loneliness, and this wall will give the building an extreme longitudinal tension. Thus his palace will not be the cube, the square of the Renaissance, he will continue the medieval linear tradition, tradition in part of the new style, and will propose a long nave, memories of a world that was a way to God, he will take up the tradition of the Romanesque nave-palaces, of the incredible nave and tower palaces of the Navarrese Gothic.

By rejecting the Renaissance cube and opting for the nave, for the great megaron, he approaches the Greek spirit, consciously or unconsciously, and distances himself decisively from the Roman world. This disdain for Roman and Italian Renaissance architecture will lead to a great confrontation between the architects of the Spanish New Style and the Renaissance architects, the climax of which will be the confrontation between Rodrigo Gil de Hontañón and Juan de Herrera.

Photo 3. Drawings of the Baigorri palace, by Juan Carlos Valerio.

Our architect has rejected the courtyard, has rejected the cube, and is heading towards a typology of a large nave, a large megaron or temple, with a disturbing interior wall. On either side of the great wall, he places two very long diaphanous bays, like great halls to the east and west, which will accompany the wall along its entire length. Practically deciding the silhouette of the building with a large longitudinal ridge and a large gable roof, its silhouette is already another novelty.

I imagine those great halls, immense, coffered, with their stuccoed walls where perhaps he imagined frescoes or tapestries, but now the great novelty will appear, the one that involves the absolute alteration of the models: he uses the columns of the courtyards outside, and creates a very high gallery of columns that shelters the two levels of the palace, the level of entrance and the noble level that looks to the outside. But as decisively as possible, he places a large gallery to the east and another identical one to the west, the violence of this decision is such that it will mean taking his ideas to the end.

The decision was implicit in the interior wall: the building will be symmetrical to east and west, the two large galleries, needless to say, will accompany the entire length of the nave. The Renaissance palace has been inverted, the architect is proposing a gigantic Parthenon, but to further accentuate his violent decision he opts for the south and north facades to be absolutely blind, except for two impressive square openings, there could be no more disregard for convention.

I have never seen anything like it, there is nothing like it in European architecture, there has never been anything like it.

Through the Age average the New Style has come to Greece, to a new Hellenism where landscape is everything.

Because that is what the building wants to reflect, with a blind wall inside, all the spatial and decorative richness was in those columns open to the landscape.

I do not even want to think what this symbolizes, the denial of the interior of the soul is followed by that ecstatic look at the landscape, man is just that, a contemplating, a watching the days and nights go by, impotent, admiring creation but without any inner refuge, an exile from God, a wandering being on a land that he admires but that is not his land, his intimate origin.

The building has sometimes seemed to me a silent prayer, but when I see its blind and black facade to the south with its two eyes, I think it is a blasphemy, how else can one understand the contempt of the south, of the sun, of life? Why only look at the dawn and the sunset?

One could say, to weaken my arguments, that it is not a palace but a belvedere, a pavilion in the landscape, maybe yes, maybe it is only a pavilion in the landscape, but how many messages! What a splendid architecture! How much hidden pain!

I often think that it is the humble counterpoint of the palace of Charles V in Granada, this square, powerful, with the most wonderful courtyard of the Renaissance, but linteled, Spanish. If Charles needed all the composition and decoration of the Renaissance, this one does not need moldings to tie the building together, it is enough with its tension, with its proportions.

Sometimes I think that the palace of Charles V represents a man, with his armor, and that this palace of Baigorri would be a woman, the former static, the latter dynamic, the former concentrated inside, the latter turned to the outside, but if the palace of Charles comes from a long tradition of treaties and advances, this one appears as a child of the Age average, plenary session of the Executive Council of naturalness, of naivety, like a first birth to the light.

It has been many years since I have seen him again, I cannot because of the sadness it would cause me, when the whole manor of Baigorri, belonging to the Duke of Alba, was sold to the farmers and the government of Navarre, the fires started in the oak groves, the beautiful Romanesque capitals of the church were looted, the government's own bulldozers demolished the old inn for no reason, the looters knocked down the tall columns of the palace to take away the drums of the columns, the capitals, it is the reflection of a time of looters.

How much I miss the Count of Lerin, they say that he took justice into his own hands, that he was a cruel condottiero, how many hands would he cut off today!

The new style would die under the dictatorship imposed by Juan de Herrera and Philip II, both, no doubt, had a new architecture, magnificent and powerful, to propose, but they truncated a new, Spanish, luminous style, and I do not stop longing for that palace floating in the landscape, that Parthenon of knights heirs of the Age average, of solitary condottieros who longed for paradise and forgiveness.

Photo 4. Drawings of the Baigorri palace, by Juan Carlos Valerio