The piece of the month of May 2017

EMBROIDERED MITRE OF PATRON SAINT SAN FERMÍN

Alicia Andueza Pérez

PhD in History of Art

If there is one religious image that unites and evokes the fervour and devotion of the faithful of Pamplona and Navarre, it is that of patron saint san Fermín. For this reason, over the centuries it has been the object of numerous gifts and donations, especially during the centuries of the Baroque period when Navarrese society experienced the taste for wealth and luxury typical of the period. In fact, its chapel, located in the church of San Lorenzo and which this year marks the third anniversary of its inauguration, was built thanks to the support of Pamplona City Council and the donations made by many absent Navarrese citizens. Both contributed to ensuring that the image of the saint, co-patron saint of Navarre since 1657, had a place that was suited to its dignity and importance. But in addition to the donations in cash, from that time onwards many gifts were received by San Fermín, both to decorate the effigy itself and to provide the chapel with everything it needed. Jewellery such as chains, pectorals or rings; trays, jugs or pediments, and various ornaments and textile pieces, gradually formed a valuable treasure that was completed with the work undertaken by the town council itself, which, having set itself up as patron of the chapel, was responsible for maintaining the proper decorum of the image of the saint and his cult.

Focusing on the art of weaving and embroidery, it should be noted that the chapel of San Fermín had its own set of liturgical vestments. In addition, the saint owned several cloaks that made up a wardrobe that was not very numerous but which included rich silk fabrics and gold and silver embroidery. Most of these works arrived at the chapel during the 18th century, some by donation and others as a result of commissions from the City Council, in which case they usually bore the embroidered coats of arms of the city of Pamplona as a distinctive feature of their board of trustees. However, the truth is that, to a large extent, these ornaments and cloaks have not survived to the present day due to the fragility and vulnerability of the materials used in their manufacture. For this reason, the pieces that have survived, such as the crimson, gold-embroidered robe that arrived at the chapel from Zaragoza in 1788 and which is worn on the main feast day of 7 July, or the gold-embroidered cloak given to the saint in 1807 by the former bishop of Pamplona, Don Lorenzo Igual de Soria, are a good example of those that once made up the saint's textile trousseau patron saint.

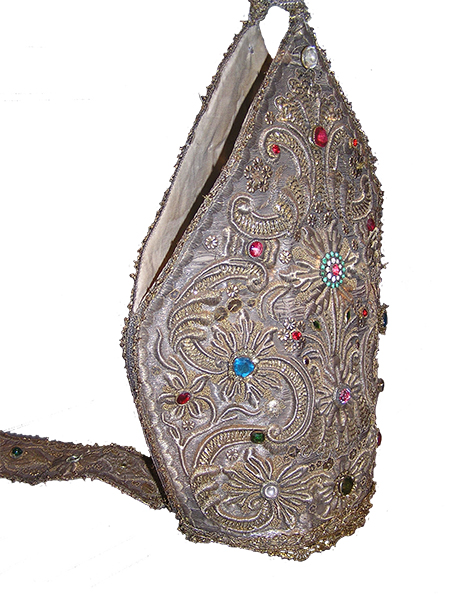

Among the textile works that currently make up the treasure of San Fermín, it is worth mentioning, due to its uniqueness, a rich embroidered mitre that the then bishop of Pamplona, Don Juan Lorenzo Irigoyen y Dutari, presented the saint with in 1778. The documentation records that on 5 July 1777, the City Council presented the Obrería de San Lorenzo with "a rich mitre for the glorious Patron Saint San Fermin, embroidered for the purpose with flowers of gold very well cut and embellished, on a silver field and strewn with different green and reddish-blond grown stones", which the bishop had given as a gift.

Photo. 1. Juan Lorenzo Irigoyen y Dutari, Bishop of Pamplona

It happened that having "put it on the saint for the function and procession of the seventh day, it was noticed that because it was very large it did not fit his head, so that in order to prevent it falling off in the procession it was necessary to secure it with ribbons". The donor was asked to compose and adjust the size of the mitre, but seeing that this was not possible, the bishop decided that another of the same quality but with a smaller mouth should be made. This was done and on 10th June 1778 the municipality handed it over to the Obrería to be kept together with the rest of the saint's jewellery and ornaments. In fact, in the subsequent inventories that were made of the objects that formed part of the chapel, together with various sacred vestments and several cloaks, the work is recorded as a mitre "embroidered with fine gold and adorned with various false stones that was a gift from the bishop Don Juan Lorenzo de Irigoyen y Dutari".

Photo 2. Embroidered mitre given to Saint Fermin by Bishop Juan Lorenzo Irigoyen y Dutari in 1778.

As stated in the donation document, this mitre, which measures 41 centimetres high and 29 centimetres wide, is made up of a background composed of silver threads that extend lengthwise over a white silk base that is completely covered. On the silver field, it has a rococo-style decoration that follows a symmetrical, ascending outline of great dynamism. On both the front and the back, both ending in a point, the vegetal motifs of flowers and stems are arranged along the central axis of the piece, combined with opposing 'ces' and linked ribbons that unfold, in an undulating rhythm, along the sides of the piece. The main motifs alternate with smaller ones that form flowers and tendrils and dot the background. On the other hand, the infulas, ribbons that start at the back of the mitre at the nape of the neck and extend across the back, measure 28 cm long by 6 cm wide and are decorated with flowers and plant motifs that are arranged lengthwise until they end in a golden fringe. Inside, it has a white linen lining and a metal structure to facilitate its attachment to the head of the saint.

Photo 3. Mitra with the infulas

Photo 4. Mitra

Photo 5. Mitra

Technically, this work is a clear example of the possibilities offered by metallic or precious metal embroidery, which was so important in the 18th century. Most of the embroidery is done with silver and gold thread, although there are also other metallic threads such as gold canutillo. The silver embroidery is executed using the picado technique on a rough preparation with a certain relief, the outlines of which are delimited by small silk stitches that are almost imperceptible, making it difficult to distinguish the background from the decoration. Alternating with the silver motifs are others made of plain gold in various forms, such as bricks, half-waves or small points. Gold thread also appears in the form of cord stitch, chain stitch, and in the form of flake and canutillo embroidery on modality , together with gold leaflets, studs and sequins that form small flowers and other motifs. The borders are finished with rhythmic silver embroidery in the form of waves in the shape of a braid, and with lace and trimmings typical of the period. Finally, the decoration is completed with green, blue and red gemstones, some of which appear to have been applied at a later date. The combination of the different points and materials creates different textures and volumes and, as a result, the effects of light and brightness are multiplied, contributing, together with the chromaticism of the stones, to the dramatic character of the work.

Photo 6. Mitra. Detail

It should be remembered that the mitre is one of the insignia of the episcopal dignity whose origin dates back to the 11th century and which evolved over time until acquiring its current form. Given the status of the person who wore it, it is a piece that is usually abundantly decorated and is classified into three types, from agreement according to its level of wealth. Thus we find precious mitres, golden or aurifrigiate mitres, and simple mitres. The work we are dealing with here can be classified, according to the characteristics seen here, as a precious mitre, which is not surprising if we bear in mind that its purpose was to adorn the figure of Saint Fermin at the main functions, since the saint, as bishop, is represented and dressed as such.

In fact, this mitre is not the only one that was received as a gift throughout the 18th century. In the first half of the century no textile mitre is listed in the chapel's inventories, but later it is recorded that in 1753, Domingo Pascual de Nieva and his wife gave a cloak and mitre "of gold cloth on a white field with silk embroidered borders"; and that in 1767, María Teresa Palomino, a resident of Madrid, donated a cloak and mitre embroidered in gold, in this case on a red field. An inventory of 1786 lists six mitres that were in use and another three that were no longer in use, while in 1824, after the fire that had taken place in the chapel a year earlier and in which several documents, objects and ornaments were lost, only three of them remained: a purple one with gold flowers, another in gold tissue and the one donated by the bishop. To these woven and embroidered pieces must be added the precious gilded silver mitre which, with a matching crozier, was sent from Mexico in 1766 by Don Felipe Iriarte and which the saint still wears today in the procession on the 7th. Currently, including the latter, San Fermín has four mitres, the one we are analysing here being the only one of a textile nature.

Finally, as for the donor of this piece, Don Juan Lorenzo Irigoyen y Dutari, a native of the Navarrese town of Errazu, after occupying a dignity in the cathedral of Pamplona for twenty years, was appointed bishop of Pamplona in 1768, position which he held until his death in 1778. During this time, in addition to his pastoral role, he undertook some actions as a promoter of the arts, such as those undertaken in the sanctuary of San Miguel de Aralar, those carried out in his hometown or the erection of seminar council of San Miguel de Pamplona. In this context, we can frame the donation of this valuable mitre, whose submission was completed after the bishop's death. In addition, it should be noted that the episcopal insignia of the prelate are preserved in Errazu and, among them, the mitre that he used in the most important celebrations. The latter has the same decorative outline as the one we are studying here, and although it cannot be compared in terms of richness and enhancement with that of the saint patron saint, they could share the same origin and author. We do not have any data to report in this regard, but it is not risky to suggest that they may be, in both cases, Zaragozan manufactures. In the Navarre of the seventeenth century, only a few embroiderers are documented and in no case did they form a workshop like the one that existed in Pamplona in the previous centuries. For this reason, during the 18th century, the parishes and institutions of Navarre ordered their ornaments and textile pieces from various foreign centers, such as Lyon, Toledo, Barcelona and especially Zaragoza. This city experienced at this time an important peak in the art of embroidery, mainly around the workshops of the artisans José Gualba and Francisco Lizuáin. Precisely the latter is the author of the aforementioned crimson robe commissioned by the City Council of Pamplona to serve in the main functions of the chapel and his workshop is possibly also responsible for one of the richest cloaks with which the saint is dressed today. In one way or another, the mastery of the work speaks to us of an embroiderer or workshop of the first order.

Photo 7. Mitra. Parish of Errazu

In addition to the richness and quality of this mitre, which reflects the characteristics of the embroidery of the period and the taste for the decorative character typical of Rococo, it should be added that this subject of liturgical pieces was not as common and numerous as other sacred vestments and that this is one of the few examples we know of in Navarre that has survived to the present day. Its function of adorning the image of San Fermín increases its uniqueness and undoubtedly contributes to evoking the ornamentation and luxury that once surrounded the religious ceremonial surrounding the saint patron saint.

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND DOCUMENTATION

-file Municipal de Pamplona, Asuntos Eclesiásticos, board of trustees de San Fermín, Legajo 15, 17 and 21.

-ANDUEZA PÉREZ, A., "Presencia del bordado zaragozano en la Navarra del siglo XVIII", in Presencia e influencias exteriores en el arte navarro, Cuadernos de la Chair de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro, nº 3, 2008, pp. 673-685.

-ARDANAZ IÑARGA, N., "Insignias episcopales de don Juan Lorenzo Irigoyen y Dutari", report 2006 of the Chair de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro, Pamplona, Chair de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro, 2006, pp. 223-225.

-ARDANAZ IÑARGA, N., "Promoción artística de Juan Lorenzo Irigoyen y Dutari, obispo de Pamplona (1768-1778)", in Promoción y mecenazgo del arte en Navarra, Cuadernos de la Chair de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro, nº 2, Pamplona, 2007, pp. 63-97.

-MIGUÉLIZ VALCARLOS, I., "El tesoro de San Fermín: Donación de alhajas al Santo a lo largo del siglo XVIII", in Promoción y mecenazgo del arte en Navarra, Cuadernos de la Chair de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro, nº 2, Pamplona, 2007, pp. 297-320.