The piece of the month of November 2017

A RETROSPECTIVE LOOK AT THE CHURCH OF SAN SATURNINO DE ARTAJONA: THE DESIGN OF THE PAINTER JUAN CLAVER IN 1606.

María Josefa Tarifa Castilla

University of Zaragoza

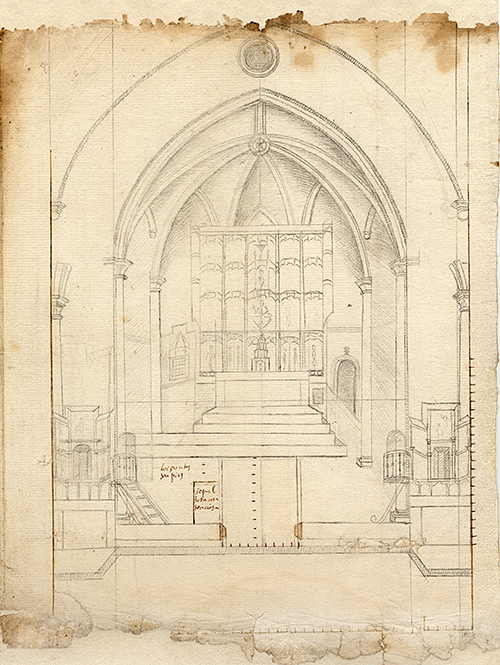

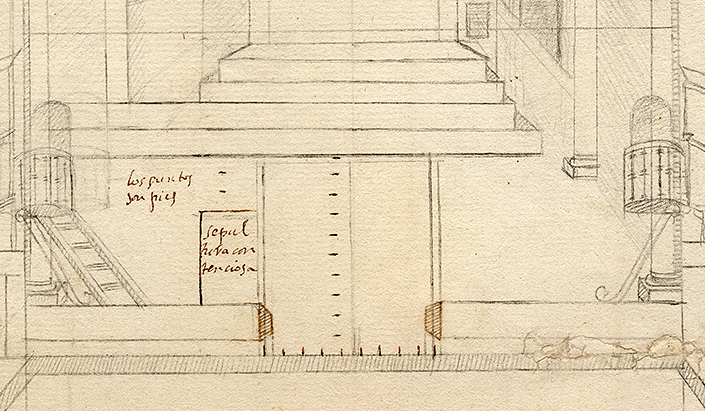

In the General file of Navarre, in the cartography section, a trace of the main chapel and the adjacent section of the nave of the church of San Saturnino de Artajona is preserved (Generalfile of Navarre, FIG_ CARTOGRAPHY, N. 345). A religious building of great importance in the artistic panorama of Navarre, since it is an imposing fortress temple located in the heart of the best preserved medieval walled enclosure of Navarre, built throughout the 13th and 14th centuries over a previous one on the occasion of the high demographic growth experienced by this town of royal lordship, which was under the patronage of the Expectation of Our Lady until the consecration of 1126, when it was dedicated to San Saturnino. The drawing under study, made on paper with pencil (50.5 cm high x .5 cm wide), sample the elevation of the pentagonal main chapel and the first section of the widest single nave of this Gothic church of San Saturnino as it was in 1606, showing the ribbed roof of the five-sided polygonal chancel, presided over by the main altarpiece that covers the front of the altar and the two collateral altarpieces and pulpits in the first section of the nave. The architectural space at the front of the church has been reproduced with great fidelity, as we can still see today (Fig. 1 and 2).

Drawing of the main chapel and next section of the nave of the church of San Saturnino de Artajona, by the painter Juan Claver, 1606. file General of Navarre.

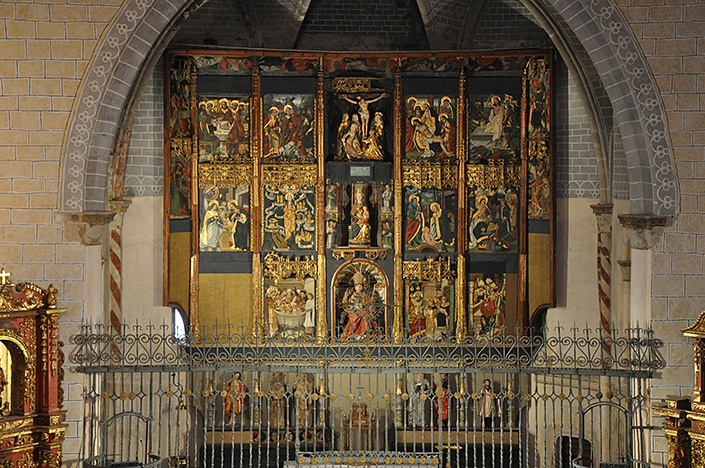

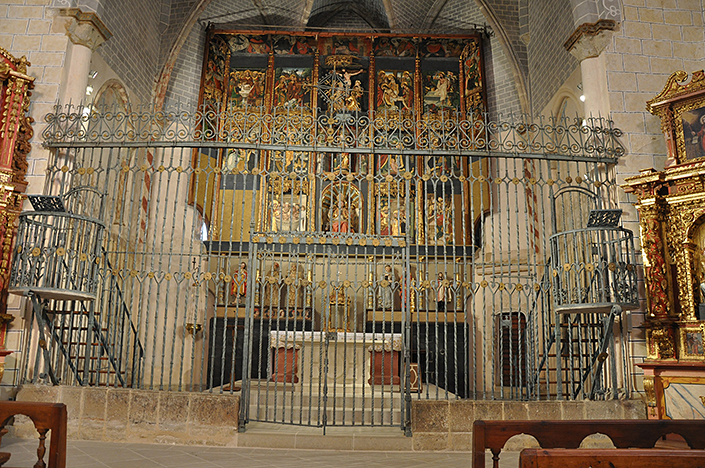

Fig. 2 Church of San Saturnino de Artajona. View of the interior from the nave towards the chancel. Photo: M.J. Tarifa

The elaboration of this meticulous drawing had its origin in the dispute that took place in March of 1605 between the parishioners of the referred Navarrese church of San Saturnino de Artajona and a neighbor of the town, the ensign Carlos de Ollacarizqueta, for the privileges derived from the possession of the tomb that this nobleman had in the interior of the main chapel, towards the side of the gospel or left lateral and next to the grille that separated the presbytery from the nave. The aldermen of the town demanded that Ollacarizqueta remove the mourning cloth, wax and offerings that he had placed on the tomb, which caused the nobleman to initiate a lawsuit in the Navarrese royal courts against the governors of the town, considering that they were limiting his private rights of use of the tomb (AGN, Tribunales Reales, Procesos, Sig. 002163), a judicial process from which we extract the news that we present below.

In the month of June 1606, the ensign Ollacarizqueta requested the court "that a painter at the expense of both parties and with attendance of them to draw the traça of the main chapel of the church with the measure of the rods of measuring cloth of the width and length of the said chapel and the collaterals, and of the distance of the contentious burial of the foot of the altar and of the half of the main chapel, and also of the length and width of the body of the whole church". Said application was attended to by the Navarrese royal committee , who on July 1 ordered "that a painter be sent to take the design of the main chapel where the contentious sepulcher is in a certain way".

The artist in charge of the design of the main chapel of the church was Juan Claver (1576-1630), a resident of Pamplona, who from 1615 held the prestigious position of overseer of the painting works of the Pamplona bishopric, position , undoubtedly one of the most outstanding masters of oil painting and polychromy in Navarre in the first third of the 17th century, as Echeverría Goñi has studied in depth. A painter who was also an excellent draughtsman, as is also revealed by the magnificent tracing drawn a few years earlier, in 1606, for the altarpiece of the Pietà in the cathedral of Pamplona. Claver had completed the design of the church of San Saturnino de Artajona by July 12 of the present year of 1606, when he testified in the lawsuit and presented this graphic design , in which his mastery of drawing was made clear in a way A , design This graphic was attached to the documentation generated in the judicial process where it has been kept throughout the centuries, although for its optimum conservation it is currently kept and forms part of the cartographic collections of the file General of Navarra, after being restored in 2008.

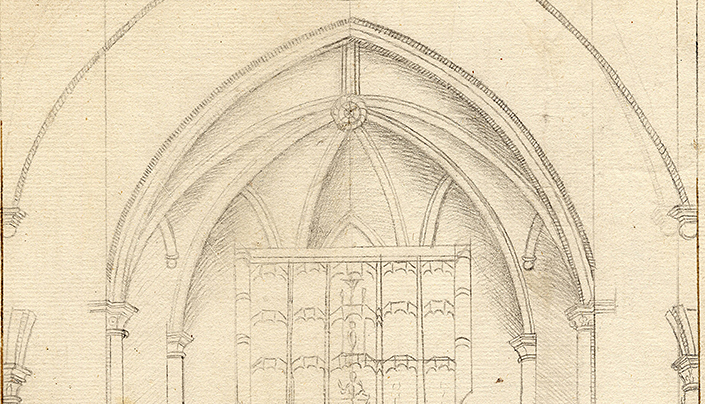

Juan Claver's drawing faithfully reproduces the elevation of the Gothic polygonal chevet of the church of San Saturnino de Artajona, executed between 1260-1270, with five panels, the two western ones being parallel, as well as the eastern wall of the nave, perfectly connected to the main chapel, a wall perforated by a circular oculus at the top and through which runs the sash arch that delimits the first section of the nave resting on corbels. The painter draws with precision the vault of the main chapel, formed by six ribs and a ligature that converge in the central circular core topic decorated with a crown of leaves, a ligature that in turn connects the core topic of the vault with the core topic of the embouchure arch of the apse, over which the aforementioned illumination opening is placed. Also visible in the graphic design is the section of the ribs, which consist of a central arch flanked by a small arch on each side, and the formal arches in the end panels that rest on brackets located above the frames. The arch of the entrance to the main chapel and the ribs of the vault rest on columns with bases that have a plinth, on which the smooth shaft and the capital rest, without detailing the decoration sculpted on them. The painter also sketches the moulded impost that divides the five panels of the polygonal closing of the chancel into two levels of height, as can be seen in the panel on the right side (Fig. 3 and 4).

Fig. 3 Detail of Claver's tracing with the vault of the main chapel.

Fig. 4 Detail of the head of the church. Photo: M.J. Tarifa.

The analysis of the layout also allows us to see the evolution of the different projects that the church underwent during the construction process, since the first architect who undertook the Gothic nave designed the nave more leave than the present one, with the supports that can still be seen in this drawing by Juan Claver, although the master builder who succeeded him raised the height of the nave considerably. Thus, on the sides of the drawing, just above the angles of meeting between the eastern gable and the walls of the first section of the nave, the arches and capitals of what were originally the easternmost supports are drawn.

On the other hand, Claver did not trace on the walls of the main chapel the Renaissance brushwork that was applied to the vault and the upper facing of the panels, marking the quartering of the ashlars, probably for the sake of greater clarity and because it was by no means an indispensable aspect of the main drawing goal that would help to understand the configuration of the space of the chancel and the place occupied by the tomb in dispute.

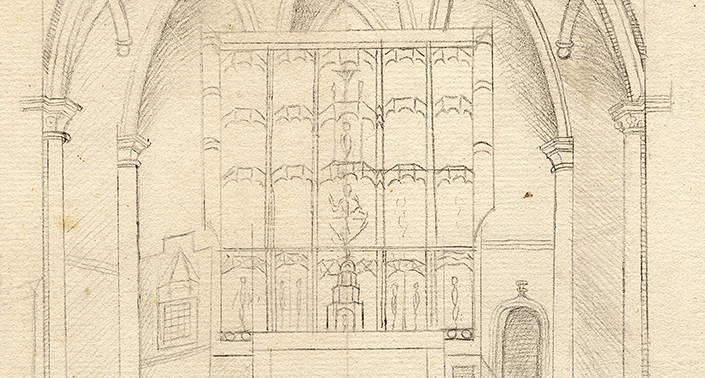

Likewise, this tracing constitutes the only graphic source known to date that allows us to know what the complete structure of the main altarpiece of San Saturnino that presided over the presbytery was like only 95 years after its completion, an altarpiece that had been executed by the painter Francisco de Orgaz between 1505 and 1511, who had the help of his disciple Floristán de Aria at partnership , and the wooden architectural structure was made by the Pamplona fusteros Maese Pierres and Maese Andrés, a late Gothic work that soon after underwent reforms and damage, until it reached the state in which it is found today. As it is drawn in the tracing, the original bank of the altarpiece was composed of five streets, as was the body of the altarpiece, and each one of these vertical divisions, articulated by slender pillars, was crowned by a canopy with openwork tracery, the altarpiece being protected by the dust cover. Thanks to this drawing by Claver, it has been possible to confirm that the bench housed sculptures arranged in niches, while the three sections had pictorial panels in the side streets, with the central one containing the sculptural images of Saint Saturnine, the Virgin and Child and the Calvary, respectively, in keeping with the pictorial cycles developed in each one of them (Figs. 5 and 6).

Fig. 5 Detail of Claver's design with the main altarpiece.

Fig. 6 Main altarpiece of San Saturnino. Photo: M.J. Tarifa

Next to the main altarpiece, on the right or epistle side of the main chapel, we can see, first of all, the access door to the sacristy from 1522, the work of Juan de Valentia, with a lowered and molded arch, culminating in the central core topic with vegetal decoration, ornamentation that has not survived to the present day. The drawing also shows the tabernacle boxed in the wall of the gospel placed in 1515 of agreement to the new cultic demands, in whose wall Juan de Asteasu worked, being this cupboard solemnized by an altarpiece that the master Egineti executed, consisting of a dust cover that protected the door of the same one, being finally this space protected and Closed from 1550 by a golden iron grill. This piece of furniture lost its function in the Counter-Reformation period, when a new tabernacle was made for the Eucharistic reservation to be placed on the main altar, thus showing in Claver's design one of the first alterations that the main altarpiece underwent with respect to its original state, with the central body of the bench occupied by a Renaissance tabernacle of decreasing bodies, that is, the new tabernacle made by Juan de Amel, a carver from Olite in 1578 and that was polychromed in 1581 by the painter Juan Beltrán de Otazu from Alava, who lived in the same town in Navarre. On the other hand, Claver traces under the main altarpiece the door that was on the right side, which gave access to a paved space at the back, the purpose of which is unknown at present.

The painter also draws the two lateral iron pulpits placed in 1595 in the mouth of the main chapel, high and with the access stairs existing at that time, since others were ordered in 1661, but not the Renaissance grille that forms a set with them and that closes the access to the presbytery, as it can still be seen today in the temple, of which only traces with a line the height of the same one, an iron fence that clearly separated the sacred zone of the high altar reserved to the celebrating clergy from the space occupied by the faithful in the nave of the temple, to whom the clergy indoctrinated in the dogmas of the catholic faith from the lateral pulpits arranged high for a better acoustics.

Claver probably made the omission of the grille in the drawing with the intention of showing the space of the chancel in a more legible way, which is why he has only traced the stone parapet placed on the floor on which the grille and the elevation of the rectangular access framework were placed, differentiating with brown ink both the ends of the stone base through which the main chapel is accessed, as well as the space occupied on the floor by the contentious tomb, as indicated by the existing annotation on it. Claver also marks with a line of brown dots that correspond to a scale of measurement in feet, the existing distance between the stairs of access to the altar and the entrance to the chancel from the base of the grating, and the width of the door of access to the presbytery delimited by the iron grille (Fig. 7 and 8).

Fig. 7 Detail of the layout with the pulpits and the grille.

Fig. 8 View of the grille and pulpits of 1595. Photo: M.J. Tarifa

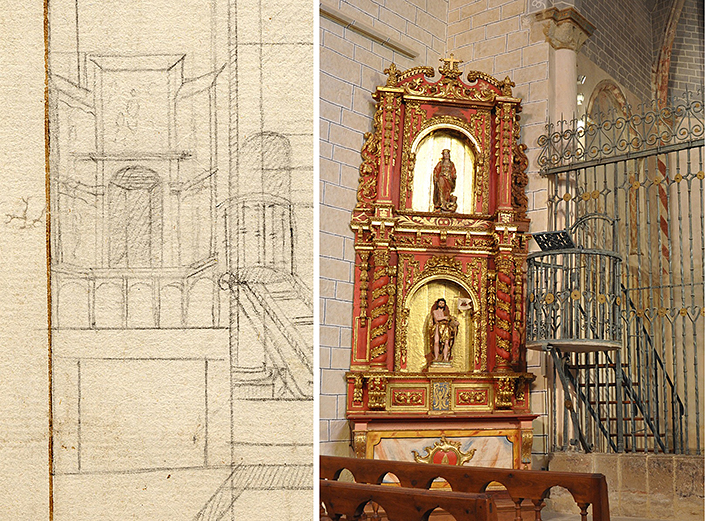

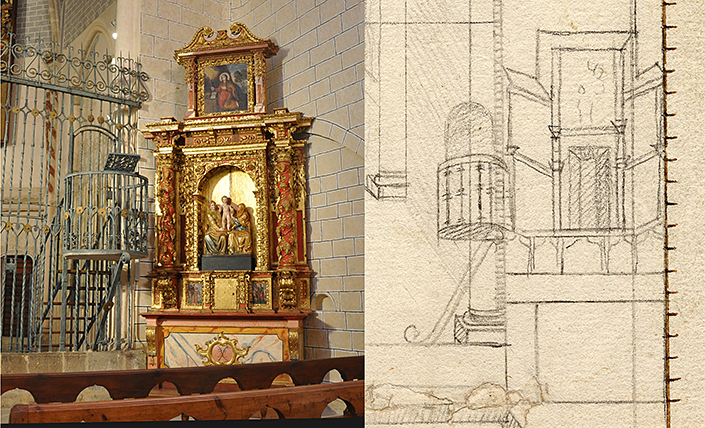

Finally, Claver delineates the two gothic collateral altarpieces of the first section of the nave with their stone altars, with cross-shaped masonry, of two bodies of three aisles, the central one larger than the lateral ones, of sculpture the images of the titulars and of painting on panel the bench, with five scenes under arches, and the remaining aisles, pieces that have not reached our days, since at the present time two baroque collaterals occupy this space (Fig. 9 and 10). From the documentation preserved in the archives it is known that the altarpiece on the left side or part of the Gospel was that of Our Lady, and the one on the side of the Epistle that of St. John the Evangelist, also executed by Francisco de Orgaz between 1522 and 1233, also at partnership with Floristán de Aria.

Fig. 9 Detail of the layout with the left gothic collateral altarpiece and view of the current baroque altarpiece.

Fig. 10 Detail of the layout with the right gothic collateral altarpiece and view of the present baroque altarpiece.

In final, Juan Claver's drawing, beyond pointing out the space occupied by the contentious tomb of the alférez Carlos Ollacarizqueta inside the main chapel of the temple of San Saturnino de Artajona, behind the stone parapet that marks the access to this privileged space, sample the mastery of the drawing by the painter from Pamplona, reproducing with great rigor and historical fidelity not only the architectural structure of the Gothic chevet of the temple in its elevation and ribbed roof, but also the artistic decoration that in 1606 was arranged in this space, with sculptural and pictorial pieces that later have been transformed, as the main altarpiece, or worse, have disappeared, as happened with the tabernacle embedded in the wall or the collateral altarpieces, and that somehow we can know and recover thanks to this graphic A design .

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

file General de Navarra, Royal Courts, Proceedings, Sig. 002163.

file General de Navarra, FIG_ CARTOGRAPHY, N. 345

Echeverría Goñi, P.L., Policromía del Renacimiento en Navarra, Pamplona, Government of Navarra, 1990, pp. 413-436.

García Gainza, M.C., Heredia Moreno, M.C., Rivas Carmona, J., and Orbe Sivatte, M., Catalog Monumental de Navarra, III. Merindad de Olite, Pamplona, Institución Príncipe de Viana, 1985, pp. 1-12.

VVAA, San Saturnino de Artajona, Pamplona, Fundación para la Conservación del Patrimonio Histórico de Navarra, 2009.

Martínez Álava, C.J. and Martínez de Aguirre, J. "Arquitectura", in Fernández-Ladreda, C. (dir.), Martínez Álava, C.J., Martínez de Aguirre, J. and Lacarra Ducay, M.C., El arte gótico en Navarra, Pamplona, Gobierno de Navarra, 2015, pp. 77-86.