The piece of the month of August 2018

THE CASA DEL MAYORAZGO DE LARRAGA, A SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NOBLE BUILDING

Pilar Andueza Unanua

University of La Rioja

One of the most significant examples of domestic architecture in the town of Larraga is known as the Casa del Mayorazgo, located in calle Sor Julia Ruiz. The name of the building, which is repeated in some outstanding civil constructions in other towns in Navarre, such as Urbiola or Allo, is in fact incomplete, as a result of the Economicsof the language and its linguistic evolution over time. Its full and original name must have been, in reality, the main house of the Rodríguez entailed estate.

Casa del Mayorazgo. Larraga. Photograph by Pilar Andueza.

The entailed estates

The entailed a series of rights, properties and assets, generally real estate, censuses and money, although they could also include movable assets such as outstanding silver objects, furniture or jewellery. At the head of all this patrimony was his palace or the family house, usually the site of surname, which was called the "main house of the entailed estate" and stood before society as the image of the lineage. As usual, rule, the new link was named after the founder's surnameand often imposed on successive owners the obligation to maintain that identifying surnamein the first place. From 1583, in Navarre, it became essential that these assets had a minimum value of 10,000 ducats and were capable of producing an annual income of 500. In the foundation deed, which was signed before a notary, the promoter or founder not only listed the assets in detail, but also established the order of succession in their possession and enjoyment. In this way, these bonds could be elective, which gave the owner freedom of choice to select a successor from among his children, but much more common were the regular entailed estates, in whose succession the eldest son and his descendants always took precedence over the younger children and their descendants, as well as the man over the woman. Although they have been detected since the leaveAge average, entailed a maximum developmentbetween the 16th and 18th centuries, disappearing in 1820 with the liberal legislation. In short, it was an institution of the Civil Lawthat prevented the partition and disintegration of the family patrimony, thus guaranteeing the economic and social pre-eminence of a lineage, as the assets were passed on from generation to generation without being diminished, since they were indivisible and inalienable. In fact, the assets could not be sold or mortgaged without the corresponding authorisation of the Royal committeeof Navarre. The payment of dowries, debts or the improvement of the assets of the entailed estate were the fundamental causes that led the owners of the entailed estates to apply forto obtain these permissions from the royal justice.

Entering into possession of an entailed estate on the death of its owner -usually the father- did not necessarily mean that he was also the heir to his free estates. However, in a large part of Navarre, where the system of sole heir prevailed, it was very common for the entailed estate and the inheritance formed by the free estates to fall into the same hands, thus reinforcing the position of the family.

The Rodríguez de Arellano family

The Casa del Mayorazgo de Larraga was, as we have already mentioned, the main house of the Rodríguez entailed estate. This saga came from the house of the Rodriguez family in the town of Arellano, from where they moved to Caparroso and from there to Larraga, where a branch of surname was established.

During the first half of the 17th century, the most important figures of this lineage were Diego Rodríguez y García and his son Blas Rodríguez y Solórzano, to whom we must attribute the foundation of the Rodríguez entailed estate, the construction of the main house and the coats of arms on the façade.

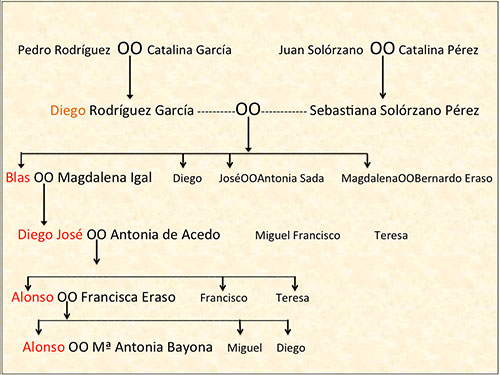

Genealogical chart of the Rodríguez family. Photograph by Pilar Andueza.

Diego Rodríguez y García -son of Pedro Rodríguez and Catalina García- and his wife Sebastiana Solórzano y Pérez -daughter of Juan de Solórzano and Catalina Pérez-, were relatives of the Saint official document. From their marriage were born Blas, who married Magdalena Igal; José, who married Antonia de Sada in Sangüesa; Diego, high school program, presbyter of Larraga and notary of the Holy official document; and Magdalena, who joined her life to Bernardo Eraso, from Mendigorría. The descent of this Ragusa family continued through the aforementioned Blas, possibly the first-born son. His life was closely linked to the degree programof arms, serving the Hispanic monarchy. In fact, he was present at the Spanish-French conflict that broke out in 1635. Accompanying the then viceroy of Navarre, the Marquis of Valparaíso, in 1636 he took part in the unsuccessful raid on Labourd (France), in which, despite the capture of Uruña, Ciborue, San Juan de Luz and the burning of Azcaine, Philip IV's troops had to withdraw without having put up a fight. Two years later, before the famous siege of Fuenterrabía, Navarre, under the command of the new viceroy, the Marquis de los Vélez, provided a levy of 4,500 Navarrese with 500 noble volunteers, including Diego, who on 4 July 1638 was appointed captain of one of the companies formed for the campaign mission statement. In this campaign he performed "particular services", such as commanding a band of arquebusiers, and fought "with great effort", as the monarch acknowledged years later. A year later he was in command of a company in the Navarrese lands of Bidasoa in the face of a new French threat, and later found himself as captain of infantry in the tercio of the Count of Javier.

But this family's relationship with the militia world was not limited to Blas. In fact, his father Diego also served "at his own expense" in an infantry company in the same conflict against the French. In 1636 he was appointed captain of the people of war of Larraga, in one of the tercios that was raised in the kingdom. Among other services, he was in charge of buying and transporting wheat and other things necessary for the army of Cantabria, while his son José -brother of Blas- was an ensign in the war of Catalonia in the tercio of the field master Martín de Mújica. Other ancestors had served Emperor Charles V in Flanders, Burgundy and Germany, according to Blas' service record. But this saga also played an important role in Larraga. Both Blas and his father Diego and his grandfather Pedro were included in the town's municipal government, and in fact Blas became mayor.

The foundation of the Rodriguez entailed estate

On 13 January 1643, the marriage contracts were signed before the notary Martín de Olcoz between Blas Rodríguez Solórzano and Magdalena de Igal, daughter of Simón de Igal, descendant of the palace of Igal in Salazar, and Polonia Terrero, neighbours of Ujué, who offered their daughter a dowry of 1,500 ducats. The groom, for his part, received from the hands of his parents Diego Rodríguez and Sebastiana Solórzano the donation of numerous goods: pieces, vineyards, censuses and money, as well as the new family house in Larraga, we believe recently built, located in the centenary of San Andrés, which had two orchards, threshing floor, corrals, barns and haylofts, as well as another house with a corral in front of the previous one. They also donated movable goods worth 2,000 ducats, 1,000 old rams valued at 2,000 ducats, 1,000 sheep valued at 1,500 ducats and 900 ewes with their lambs estimated at another 1,400 ducats. The donors, who reserved 4,000 ducats for themselves, showed in the fourteenth clause of the notarial protocoltheir desire to erect an entailed estate with all that patrimony:

All the aforementioned real estate, such as pieces of land, vineyards, house and censales from the granting of this deed onwards are to go together, united and not separated, and all of them are to be enjoyed by the said spouses after the death of the donors and they are to be owners and lords of them, usufructuating them while they live without being able to divide or divide them, And after their death they are to succeed to them their sons and daughters that God may give them, preferring the males to the females, with such quality that in the said bond the first to succeed is the son or daughter who is most appropriate and who seems to them to be the most appropriate.

It was therefore an elective bond for whose succession Blas was now designated, imposing on those who entered into its enjoyment the obligation "to bear the name of the Rodriguez family, all keeping the aforementioned order". This estate was progressively enriched over time with new additions made through the corresponding documents, among which we would like to highlight a few. Thus, on 12th October 1660, Blas granted his will, ordering his burial in the parish church of Larraga, where his wife Magdalena was buried, and ordering the celebration of 4,000 masses in suffrage for his soul. He left different portions of wheat to the hospital of Larraga, to the basilica of Nuestra Señora del Castillo and San Andrés and to the hermitages of San Esteban, San Blas, San Gil, San Lorenzo and San Guillén. In this document, he stated that during his marriage he had acquired new assets with his wife, which he now added to the entailed estate. These included the palace and armoury of Amátriain (Leoz) with a call to the Cortes, the neighbourhoods of Olleta, Maquirriain and several censales. He named his son Diego José as heir to his estate, as well as successor to the related assets. The death of Blas and the minor age of his successor, Diego José, placed the grandfather, Diego, once again at the head of the saga, taking over the grandson's tutorialand the management and administration of the family assets. And as such, and despite the aforementioned deeds, still on 18th December 1664, again before Martín de Olcoz, grandfather Diego granted the deed finalof foundation of the Rodríguez entailed estate "for the preservation of my house, descendants and successors of it for perpetuity so that they may have renown, grow and increase the status of it in perpetuity", adding among other assets another house located in the centena of San Miguel, which we believe currently corresponds to an emblazoned house, with a very battered façade, located at placede la Picota, as can be seen from its coat of arms, which includes in its quarters the arms of the palace of Amatriain and those of the Rodríguez family in the first quarter, those of the Solórzano family in the second, the García family in the third and the Pérez family in the fourth.

House of the Rodríguez family at placede la Picota de Larraga. Photograph by Pilar Andueza.

Diego Rodríguez Igal married Antonia de Acedo and they gave birth to Alonso, who married Francisca Eraso y Amézqueta. In 1717, after Alonso's death, his widow again added assets to the entailed estate, and a year later she made an inventory of assets that is of great interest as it allows us to know some details of the entailed estate, such as the 10,000 ducats levied on the town of Larraga in 1701. Linked to the entailed estate were also some important pieces that were used to furnish, dress and furnish the family home. These included several silver objects weighing 47 pounds: a large gilded source, a gilded jug, a candle holder, a candlestick, a workshop, two salvers, a basin, twelve saucers and a gilded saltcellar, sugar bowl and pepper shaker. There was also a piece of jewellery consisting of a choker and crystal and gold earrings. There were also five pastry cases with the arms of Emperor Charles V, seven paintings with the history of Jacob "originals of Basa", another six with religious themes, a very large one with Saint Ignatius and Saint Francis Xavier, and another large one with the venerable Friar Ignatius of Gerona, General of the Capuchins. On the walls of the house hung five portraits of members of the family, as well as six portraits of the house of Austria, together with several portraits of countries, stations and fruit trees. Four mirrors and three maroon canopies and various objects from the chapel(a painting of the Immaculate Conception, a lump of the Immaculate Conception, a small painting with a gilded framework"painting of Rome" of Saint Sebastian and various reliquaries) completed the movable property of the entailed estate. Other objects, already outside the bond and distributed around the Larraga house, were chests of drawers, chests, desks, chests, beds with their hangings, braziers, or Muscovy cowhide chairs with gilded nailheads.

The palace of Amatriain

From the second half of the 17th century, the Rodríguez de Larraga family were able to attendto the Cortes Generales of the kingdom in the arm of the knights thanks to the seat granted to them by the possession of the palace of Amatriain (Leoz). This palace came to the Rodríguez entailed through a donation. In fact, late in the 16th century, María de Egüés was the owner of that noble plot, who in her will of 1578 bequeathed it to her son Fermín Ladrón de Cegama, surnamein whose hands the property remained for several generations until 1649, when its then owner, Juan Ladrón de Cegama, died, on the occasion of the marriage contracts of José Rodríguez y Solórzano, from Larraga (son of Diego Rodríguez and Sebastiana Solórzano and brother of Blas), with Antonia de Sada, donated the palace to the aforementioned Antonia with his summons to the Cortes because he had brought her up in his house and because he considered himself a kinsman of José. Some time later, on 28 January 1653, José and Antonia ceded the palace and its belongings to his brother Blas, which allowed him to incorporate it into the Rodríguez estate in his will of 1660. Previously, on 29 October 1655, Philip IV issued a royal decree in Madrid recognising Blas's possession of the palace and his right to attendto the Cortes in the arm of the nobility for the aforementioned palace.

The main house in Larraga

In the Middle Ages, averageLarraga developed urbanistically on the slopes of a hill, under the protection of the castle that crowned the promontory and overlooked a very large area of Navarre, which led to an irregular layout, with long, broken streets, adapted to the topography. However, as in other Spanish towns and villages, the Modern Age brought with it, from the 16th century onwards, the expansion of the hamlet towards the plains, giving rise to new extensions with more regular streets in which new buildings and larger squares were built. And it is precisely in this context of urban expansion that we must place the house of the Rodríguez family, which we believe must have been built in the years immediately prior to 1643 by Diego Rodríguez García and his son Blas Rodríguez Solórzano. In a visual culture such as the Baroque one, the construction of a house with a stately appearance was essential as an image of the lineage, as it provided information on the economic and social position of its inhabitants, proclaimed their nobility through their coats of arms, and became part of the fame of its owners.

Front of the Rodríguez house. Photograph by Pilar Andueza.

The Rodríguez house corresponds to the typology of noble domestic architecture developed in the 17th century in the area averageof Navarre. Its façade, with a markedly horizontal format, has three levels and is built entirely of brick, except for a stone plinth made up of five rows of ashlars, a material that is undoubtedly more resistant to erosion and the passage of time than terracotta. The doorway, formed by a bell-shaped arch, is set off-centre, and is flanked by simple rectangular windows with wrought iron grilles with simple vertical bars of quadrangular section that cross through openings in the same horizontal section.

Window of the Rodríguez house. Photograph by Pilar Andueza.

The main floor opens out onto the street through four open balconies without overhangs protected by chiselled wrought iron parapets formed by a central knot and plates. The two central openings are placed closer together, and between them and the two ends are two large heraldic inscriptions that date from 1660, according to the accusation that Diego Rodríguez García received at that time for having placed the coats of arms on his house in Larraga. He was acquitted by the Navarrese courts in a ruling on 27 April 1663, granting him and his grandson Diego José permission to display them. Both coats of arms have a similar structure, with lions bearing, a lower mask and a helmet with a large plume as a bell. The fields appear on a cartouche of twisted leather and on a military cross, typical of the Amatriain palace. Of the specimen above the door, we have only been able to identify the second quarter, corresponding to the palace of Igal (Salazar). The other coat of arms, divided, has what we believe to be a mixture of the arms of the palace of Amatriain and the Rodríguez family in the first quarter, while the second quarter, in turn divided, bears the arms of the Solórzano family at the top and the García family at the bottom.

Coat of arms. Photograph by Pilar Andueza.

Coat of arms. Photograph by Pilar Andueza.

The façade is crowned on the third level by a gallery of double semicircular arches, which we must relate to the architecture of the middle Ebro valley, which had a great developmentin the Ribera and a large part of the area averageof Navarre, and whose influence even reached Pamplona.

Inside the house, the hallway stands out, with the floor decorated with pebbles, the quadrangular staircase with turned balusters at the corners, as well as the chapel, presided over by a small altarpiece of the Immaculate Conception.

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

fileGeneral de Navarra, Proceedings, no. 164841.

fileGeneral de Navarra, Proceedings, no. 259287.

fileGeneral de Navarra, Procesos, no. 300720.

fileGeneral de Navarra, Notarial Protocols of Martín de Olcoz (Larraga).

ANDUEZA UNANUA, P., "La arquitectura civil", R. FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA (coord.), El arte del Barroco en Navarra, Pamplona, Gobierno de Navarra, 2014, pp. 57-107.

ANDUEZA UNANUA, P., "Architecture and municipality: the case of Larraga", lecture(22-IX-2017).

USUNÁRIZ GARAYOA, J. M., "Mayorazgo, vinculaciones y economías nobiliarias en la Navarra de la Edad Moderna", Iura vasconiae: revista de derecho histórico y autonómico de Vasconia, 6, 2009, pp. 383-424.