The piece of the month of December 2018

BELLS AND BELFRIES IN BAZTAN: DIALOGUES, SILENCES, TRANSFORMATIONS

Gabriel Imbuluzqueta

Etniker Navarra

The bells, their sound, have been so integrated in human communities, no matter how small they were, that they have directed -and direct- day by day the rhythm of their religious, labor and social life. They have marked their routines and have brightened their festivities, have frightened their fears and have been messengers of joy, have accompanied -respectfully- in the hardest moments and have alerted -solidary and anguished- of dangers and emergencies.

It is not surprising, therefore, that the people have sometimes reached such a Degree familiarity with the bells that they have somehow humanized them by interpreting what they say.

Sometimes, the popular voice has translated the sound and its rhythm reflecting in essence the message rung from the bell tower. Such is the case, for example, of the ringing of the "campanica" in Elizondo on the death of a child or infant:

Din-dilin-danda

din-dilin-danda

Our Lady is calling you

to go up to heaven

with a candy

to make the cradle

to the Baby Jesus

who comes tired

from carrying the cross.

Photograph by Miguel Imbuluzqueta.

In others, however, the misrepresentation of the message is as obvious as it is crude, and its only intention is to hurt, tease and tease the neighbors in the next town.

So it happens (perhaps it is more correct to say it in the past tense, "ocurría", because only some older people know it) when the neighbors of Elizondo imitate the rhythm of the bells making them say:

Elbete, kukute,

mando zar bat hil dute.

Plater txar bat ezin izanez,

zerri azpilian jan dute.

(Elbete, kukute,

they have killed an old mule.

As it can't be in an old dish,

they have eaten in the pig trough).

(Perhaps a more accurate translation is "gamella of the pigs").

In response, the residents of Elbete address the residents of Elizondo with a chant that tries to imitate the ringing of their bells:

Elizondo, mango,

arto gutti jango,

erresa ta papurre.

Elizondo hanka makurre.

(Elizondo, mango,

will eat little corn,

bran bread and crumbs.

Elizondo, crooked paw [or leg]).

On the text of the mockery dedicated by the elizondarras there are different versions with such small differences (substitution of a word) that they are almost inappreciable and that are a consequence, probably, of the oral transmission.

In some versions the "mando zar bat hil dute" ("they have killed an old mule") is changed to "mando zar bat jan dute" ("they have eaten an old mule"), which seems less correct because the verb "hil" ("to kill") fits better than "jan" ("to eat") in the context of the verse and also avoids the reiteration in the final line of the verse.

In another version the change occurs when, instead of "Plater txar bat ezin izanez" ("As it cannot be in an old dish"), "Kattilu zar bat ezin izanez" ("As it cannot be in an old bowl") is chosen.

On the other hand, some details can be noted that, without further pretensions, could be nuanced. For example, the employment in the same stanza of the forms "zar" and "txar" ("old"). It seems more logical to use the same version in both cases: either "zar" or "txar" (in principle, the 'more official' variant of "zar" would be more acceptable; the Real Academia de la language Vasca-Euskaltzaindia admits only "zahar"). Another phonetic change reported among the different informants is the employment of the "s" instead of the "z" in the verbal form "aspilian" (from agreement with the dictionary, "azpilian" should be used). In any case, the difference, apart from being anecdotal, is not of the slightest importance, given that we are dealing with expressions collected orally. There are also phonetic variations, besides "zar" and "txar", "zerri" and "txerri", "jan" and "yan"; in this respect, the Basque speakers of Baztan always pronounce "yan", although in writing "jan" is used. (At this point, and even at the risk of digressing, it is worth noting that in the classic speech of Baztan, still maintained by elderly people, "eskualdun" is used instead of "euskaldun" and "eskuara" for "euskera" or "euskara", a localism that gave its name to a festival in support of the use of the Basque language called "Hamabi ordu eskuaraz").

Photograph by Miguel Imbuluzqueta.

Returning to the language of the bells, the residents of Elbete treasure another manifestation of derision directed at the inhabitants of Elizondo, who have to hear the bells rubbing them the wrong way.

Bakailu salda, bakailu salda

("Sopa [or broth] de bacalao, sopa de bacalao", in literal translation, but which in popular version would be as much as "sopa de borrachos, sopa de borrachos").

Other informants opt for a phonetically very similar variant, but with a different gastronomic meaning:

Bakailu salsa, bakailu salsa.

(Cod in sauce, cod in sauce).

The people of Elizondo, accusing the mockery, do not keep quiet and reply, also by clapping their bells from the bell tower,

Bai lukek, jain lukek

(If you could, you would already eat)

Note the employment of "jain" instead of "jan", perhaps due to the deformation of the popular language rather than to dialectal forms per se, which can be seen in some words. For example, in the employment of article, the ending of the words in "e" instead of "a", as, for example, "papurre", "makurre" or, in plural, "zerriek" (instead of "papurra", "makurra" and"zerriak").

On the other hand, in Lekaroz they 'hear' that the bells of Gartzain, when they see that a pig of the neighbors has sneaked in to eat in their area, they ring

Zerri landan, zerri landan

(Pig in the [crop] field, pig in the field).

In response, the people of Gartzain then 'hear' how the bell tower of Lekaroz shouts at them:

Atra zak, atra zak.

(Take it out, take it out).

There are those who refer that, while one of those involved is the town of Gartzain, the other is not Lekaroz but Irurita. Some informants slightly vary this dialogue and pluralize it: "Zerriek landan" ( "The pigs in the field"); this version also has a slight variation in the answer: "Atra zik". In both cases, the verb "atra" is a contraction of "atera" ("to take out").

Photograph by Miguel Imbuluzqueta.

With the passing of the years and generations, the musical recitations have been left aside and have been lost or transformed into "erranairuak" or popular sayings, and even into "iseka kantak" or burlesque songs, regardless of their origin in the bell towers. Thus, for example, with variations on the aforementioned stanzas:

Elbete, kukute,

apo bat yan dute.

(Elbete, kukute,

have eaten a toad).

Or this other more complete one, which coincides with what has already been stated above:

Elbete, kukute,

zerri bat hil dute.

Kattilu bai ezin izanez,

txerri aspilean yan dute.

Curiously, this verse, taken as loan of Elbete, has come to be applied also to the neighbors of Bozate, the Arizkun neighborhood historically -until a few decades ago- marginalized for being a stronghold of agotes:

Bozate, kukute,

zerri bat hil dute.

Kattilu txar bat ezin izanez,

zerri aspilean yan dute.

In any case, whether they are valued or not, the bells continue to fulfill their fundamental raison d'être: the call to prayer and worship, a meaning that they do not lose when, from a more secularized point of view, they seem to break the monotonous silence of the towns to call to the party for the party ("campaneo" or ringing of bells on the eve of the great liturgical festivals or joining the boom of rockets and chupinazos announcing patron saint festivals); or, when, anticipating to the paper obituaries or to the cell phone calls, they emit the report of deaths (previous "touch of agony" one average hour before) that also details if the neighbor of present body is man, woman or child; or when, hammering the quarters and the hours, they mark the times of the work and the daily life.

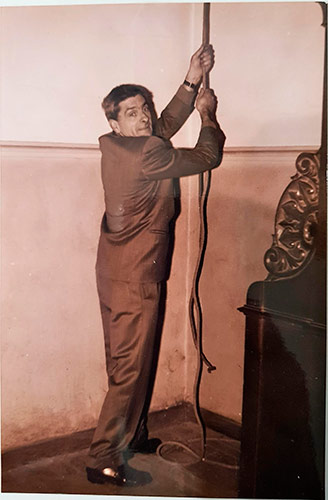

However, the bells have given up (whether they are still in use or not), due to technology or changes in social customs, some of the functions that had been attached to them. For example, the "touch of prayer" at nightfall has disappeared without remedy (and it does not seem that nobody is going to try to recover it) as a call of "retreta", of recollection in the family house. Nor is the value of yesteryear given to the chimes that, when the storms threatened mercilessly, were allied from the tower or at the foot of it with the incantations of the preste (incantations that, in the popular mind, recited in Latin were more effective). And to the oblivion has also passed, at least in Elizondo, the "batzarre", call to the popular decisive assembly in the appointment of "jury" (sworn mayor), of expenses and investments in the town or of any other questions that required the approval neighborhood. It was a call that the "secretary" of the town (nothing to do with the municipal secretary) performed at the back of the church by pulling a rope (without climbing the bell tower) at the end of the Sunday mass, a few minutes before the beginning of the "batzarre" in the "herriko etxea" or "town house".

Ángel María Olave (a) "Pistón", playing "batzarre". Photograph by Gabriel Imbuluzqueta, taken in the late 1970s.

The disappearance of a ringing like the latter means a loss of ethnological value; the same as the suppression of the figure of the bell ringer -and of his ringing-, replaced by simple electric switches or the latest computer programs. But the worst thing for the bells (after all, musical instruments) is silence. However, although it may seem a contradiction, there was a time when silence was a gesture of a deep sense of charity: during the so-called "Spanish flu", 100 years ago now, in 1918, there were bell towers (I have heard it said many times in Elizondo) that skipped the tolls of agony and death so as not to overwhelm so many sick people in a trance or at serious risk of falling into it.

The negative silence of the bells is not so much a consequence of their being muted, as when the city silences its belfries because they disturb, especially those who have made noise their banner, but because their villages have died and have been depopulated or abandoned.

Anyway, if silence is bad, verbosity can be worse. Suffice it to recall what happened to the girl in the story "Ezkilaren errana" (1945) by the Basque-French priest Piarres Lafitte, whose moral teaches that "Ezkilek eta kontseilariek ez dautzute sekulan erranen ez Balentin, ez Mutxurdin, baina tilintin!", for listening to 'what the bells say'. Or, said in Spanish, "Neither the bells nor the counselors will ever tell you neither Valentin nor Mutxurdin [spinster], but tilintin!".