The piece of the month of March 2018

HOW THE ILLUSTRIOUS RONCALESAS DEFEND THEIR HONOR, A COMEDY BY LUIS MONCÍN WITH MUSIC BY BLAS DE LASERNA. THE CLASH BETWEEN POPULAR BAROQUE AND NEOCLASSICISM

José Ignacio Riezu Boj

University of Navarra

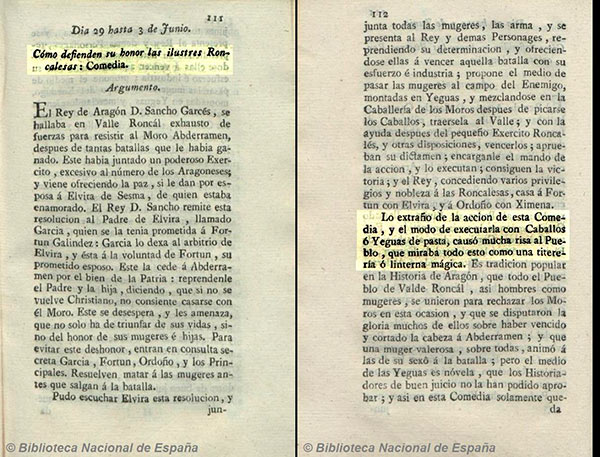

On May 29, 1784 the theater company of Eusebio Ribera premiered at the Teatro del Príncipe in Madrid the comedy Cómo defienden su honor las ilustres roncalesas. The author of the Navarrese epic was the famous Catalan actor and writer Luis Moncín Narciso and the music was by the also famous Navarrese musician Blas de Laserna. The play was performed for six days: May 29, 30 and 31 and June 1, 2 and 3, and was a great success in terms of takings. In the six days the theater earned more than 20,000 reales, with Monday the 31st being the day with the largest capacity (almost 6,000 reales were collected) (Andioc & Coulon, 1996). On the occasion of its premiere, the Madrid literary newspaper of the time, Memorial literario, which was in tune with the new enlightened airs, published the plot and critique of our comedy. Among other things it said: "The strangeness of the action of this comedy, and the way of executing it with horses or mares of paste [cardboard], caused much laughter to the people, who looked at all this as a titter or magic lantern... and so in this comedy only remains for an indecent episode, invented by the novelist or the poet" (Anonymous, Coliseo el Príncipe, company of Eusevio Rivera. Day 29 to June 3. Cómo defienden su honor las ilustres roncalesas: Comedia, 1784). The play was performed again in Madrid in 1788, this time in the other Madrid theater, the Teatro de la Cruz, by the same company of Ribera, for 5 days: from December 6 to 11. Once again, the data box-office takings guarantee its success: 17,500 reales (Andioc & Coulon, 1996). In that theatrical season, from Easter 1788 to Shrove Tuesday 1789, 67 plays were performed at the Teatro la Cruz, although only 14 of them were performed 5 days in a row, among them the protagonist of this article. The comedy was also performed in other cities of the kingdom. We have evidence that it was staged in Valladolid in 1788 (Cabezón, 2003), in Havana on February 15 and 24, 1791 (Montoya), and in Mexico City on November 28, 1791 (Irving A, 1951), on May 10, 1792 (Leonard, 1951), and in December 1793 (Viveros, 1997). In the archives of the Teatro de la Cruz in Madrid (today at the Library Services Histórica de Madrid) it is recorded that the author Luis Moncín charged 600 reales for the composition of this comedy and informs us that it was an adaptation of another play of his that had been premiered in Madrid on November 27, 28 and 29, 1778 at the Teatro de la Cruz with the degree scroll Poner a riesgo el honor, por el mismo honor y patria, y triunfo de las roncalesas (Andioc & Coulon, 1996).

The play

The comedy that we are studying is included by the experts within the heroic comedy and in the military modality that extols the patriotic ideals, the value of war and the soldier (Cabezón, 2003). Within this section a sub-section has been suggested in which the authors choose female warriors as protagonists. Up to 16 works of these characteristics have been counted in the last third of the 18th century (Cabezón, 2003).

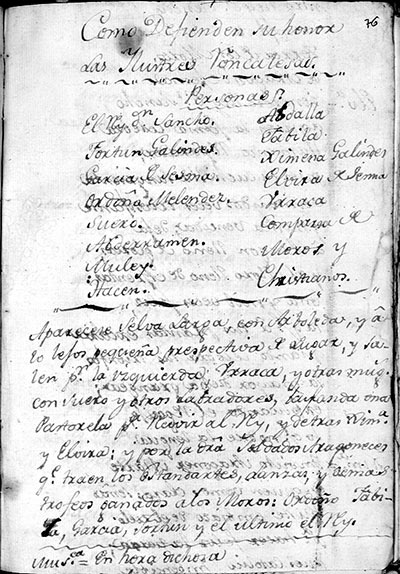

At least one manuscript copy of our work is preserved in the Archive of the University of Seville, identified as manuscript A 250/111(2) and available at network. Another copy of the work seems to exist in the Library Services Histórica de Madrid, although I have not been able to confirm this (Piñal, 1981). The manuscript at the University of Seville is bound with two other works. On the occasion of the binding it seems to have suffered a guillotining that prevents or makes it difficult to read the last line of the text on many occasions.

The play follows all the rules of baroque theater: it is structured in three acts (beginning, middle and end), the language is adapted to the social and cultural class of each character, it is written in verse, the comedy is mixed with tragedy, the themes are typical of baroque (honor, love) and the characters as well: the king, the gallant, the lady, the fool, etc.

The work seems to have had problems with censorship; all works had to pass the ecclesiastical censorship and the censor Fray Ángel de Pablo Puerta Palanco seems not to have liked the phrase "first is honor rather than life" put in the mouth of the Roncalese women, considering it contrary to the Gospel, and Moncín was forced to make modifications to the original text (Cabezón, 2003).

The comedy presents the following characters listed at the beginning of the text: the king of Aragon Don Sancho Garcés; his knights García de Sesma, Fortún Galindes, Ordoño Meléndez and Fabila; the women of Aragon led by Elvira de Sesma (daughter of García), Ximena Galindes (sister of Fortún) and Urraca; a villager named Suero; the Moorish king Abderramen and his generals Muley, Hacen and Abdalla; and the troupe of Moors and Christians.

The work, as we have already mentioned, is divided into three parts or conference. Below, we present a summary:

workshop 1

The comedy starts with the description of the first scene

There appears [a] long forest with groves and in the distance a small perspective of the place and on the left Urraca and other women with Suero and other farmers dancing a pastorela to receive the king and behind them Ximena and Elvira and on the right Aragonese soldiers carrying the banners, spears and other trophies won from the Moors: Ordoño, Fabila, García, Fortún and the last one the king.

A chant welcomes King Sancho Garcés King of Aragon and his army as they enter the Roncal Valley (curiously, both the action, the king and the Roncal Valley appear in the work as Aragonese, with no mention at any time of their Navarrese origin). The combatants are received by the Roncal women, with Elvira de Sesma at their head. Fortún asks the king to intercede with Elvira's father, García, so that he grants her hand, but at that moment a bugle sounds announcing the arrival of Abderramen's army. The Moorish king enters the scene and demands the king's surrender. Sancho refuses and Elvira comes out in defense of her king saying:

I fulfilling the illustrious

noble blood that encourages me

I would go out to give you death

that to women of my sphere

no danger frightens me

because my nobility is so great

that of many Moorish kings

a Sesma cannot be made;

and a Sesma can populate

the whole earth with kings.

The Moorish king, seeing the arrogance of Elvira, leaves with his army stunned and madly in love with Urraca. Meanwhile, Ordoño declares his love for Urraca, Fabila is offended and challenges Ordoño to a duel (they both want her). King Sancho appears and has called a meeting where he informs that they are surrounded by a much larger army and practically impossible to defeat. He offers to surrender to the Moorish king in exchange for the others to live, but they refuse and make the king swear that he will not surrender.

workshop

Fortun comes out on one side and King Abderramen on the other disguised as a Christian, Fortun converses with him believing that he is a Christian, but the Moor confesses that he is Abderramen, that he is madly in love with Elvira and that he has kidnapped her, but she has defended herself bravely and has killed several Moors. Abderramen flees when he hears voices. Elvira appears armed and comes with Ordoño and Fabila, she leaves with Fortún and Ordoño and Fabila stay behind, who want to fight a duel. Ximena appears and stops the duel, convincing them to let her brother Fortún decide who they will marry.

In a poor house the king, García, Fortún, Fabila, Ordoño, Elvira and Ximena talk about the kidnapping of Elvira by the Moors. King Sancho proposes to marry Fortún and Elvira, but at that moment a soldier enters announcing that King Abderramen is coming. The Moorish king appears with his generals and tells them that he offers to stop the war and to be their ally in exchange for Elvira, because he wants her not as a slave but as his wife. In front of them he declares his mad love:

...for she has surrendered to me

her eyes I adore lover,

her butterfly light I follow,

in her beauty I idolize,

and only by loving her do I live.

If you give her to me, of course

I offer, swear, and affirm

that I will be as long as I live

your ally and friend...

King Sancho says that the one who has to answer is García, who is Elvira's father. The father affirms that it is Elvira who must decide. Elvira replies that she has already chosen a husband and it must be Fortun who decides, although she knows that he will refuse. Fortun, after confirming that everyone (including the king) will abide by what he proposes, decides to send Elvira to the Moorish king, submit . Elvira, enraged, lashes out and repudiates Fortun in a long speech in which she also includes Abderramen:

...remove yourself from my presence

vile man, cruel crocodile,

who with feigned tears

you have pretended to devour me;

and do not come back in your life

to see me, for I already look at you

with such horror, such astonishment,

such torment, such martyrdom,

that, for not seeing thee, I will not speak to thee.

If you do not meeting another way,

I'll take myself out

with enraged spite

the heart in which you

have lived in.

and you, unfaithful Abderramen

that proud and presumptuous...

to conquer the affections,

forget then thy madness

restrain so much delirium,

and then return to your camp

without hope of relief,

that he will never be loved

who was never hated.

For the greatest torments

the most horrendous punishments,

on brave to endure them,

on constant to suffer them,

on courageous to overcome them,

on Christianity to ask for them,

rather than shake hands with you...

Fortun explains himself and declares that he offers what he loves most for peace and so that the Moorish king will be baptized a Christian. Elvira understands his motives and it is she who offers herself as wife to the Moorish king to make him a Christian. The Moorish king, furious, refuses to deny his faith and returns to apply for to give Elvira to him. All refuse and the Moorish king attacks the Christians promising to destroy the valley, kill the men and rape the women:

...I shall not leave in this valley

stone, plant, tree trunk or visqueen

that does not burn, that does not burn;

feeling my courage,

that I cannot many times

to do the same destruction.

There shall not be a single man left

whom I will not put to the sword

committing my rigor

even the most tender children.

Thus I will avenge my rage...

...

...For moments to prevent you

to death and affront,

for in my rage I determine

to run over women

to punish men...

Everyone withdraws except Garcia and his men who, gathered together, decide to kill their wives and daughters that same night to avoid the outrage promised by the Moor. They also resolve to face the Saracens the next day and die all together. Meanwhile, a hidden Elvira has heard everything.

workshop

In a poor house García and Fortún cry about their misfortunes for having to kill the women. Elvira and Ximena appear and interrogate Fortún about his affliction and he leaves very dejected without being able to say anything. Elvira and Ximena go in search of the women while the king and his men appear and decide to start the battle at dawn knowing that it is certain death. The women appear armed with children and girls and, to the astonishment of the king and his men, Elvira tells them that she knows their intention to kill them before going into battle. Elvira asks the king that they too take part in the fight against the Moor:

...since this being the case, to beg

we come determined

that we women form

the body of the vanguard;

for which we have already come

with the hard steel armed;

in this we are determined,

courageous and brave

We will not turn our faces away from danger or death

we will not turn our faces away;

Do not make difficulties

that will not be of importance.

We want to die killing

because time applauds us.

In this resolution

we come so bold

that if you want to deprive us

we, without any other financial aid

we shall give battle,

and all of us will know how to die

with courage and constancy,

to see that you answer us,

warning, that you have wronged us

you have us and so you can

and so you can leave us unloosed.

So that the world may know

how, with such a great deed

the illustrious Roncalesas

defend and guard their honor.

Elvira, angered to see that the men and the king are hesitating, tries to stab herself with a dagger, saying that this way someone else will not kill her. Everyone quickly stops her.

The king, admired by the courage of Elvira and without knowing the intention that the men had of killing their women, accepts the proposal of the Roncalesas and resolves to name Elvira general of the Christian army:

...and for our greater glory

the general shall be the general

that Elvira Sesma commands her,

whatever she commands and whatever she does

we must all obey;

this rare preeminence

women deserve today

for when they long for the feat

of dying at our side

it is a necessary action to honor them.

Ea vassals and friends,

and gallant amazons

to die for our faith...

Elvira takes command of the army and orders to start the battle at that very moment before the enemy army can rest. Elvira organizes each captain in his post: "Fortún at the ambush bridge, Ordoño at the mill point, Fabila in the ravine to prevent the enemy's retreat, men with axes hidden by the bridge and the boys and girls by some high rocks. The king and his father in the rear". Finally, he proposes to send the women to the Arab camp mounted on mares to excite the horses and lead them, with the Muslim army, to the bridge and the rocks, where the Christian army awaits them.

Everyone accepts Elvira's orders with enthusiasm and they go to battle. The Moorish army appears with its king giving orders to rest and not to leave any Christian alive. At this moment the manuscript describes how the scene should be: "all the Christian women pass on horseback on the mares and if it could not be painted imitating them and in particular Elvira and Ximena and they enter by the right". The Moors with their horses follow the mares that lead them towards the bridge and the crags, where the meeting between Moors and Christians takes place. While they fight, the women appear on foot, and between men and women they manage to surround the Moors, all of them dying except King Abderramen who, wounded, flees pursued by Elvira. When everyone misses Elvira, she appears with the head of the Moorish king. King Sancho grants nobility in his honor to all the Roncalesas:

Invincible Roncalese,

prodigy, astonishment and joy

that will make time memorable

to you we owe the glory

of this admirable event,

your gallantry and ingenuity

from such a blind labyrinth

so successfully brought us out of such a blind labyrinth.

And so in just reward

I grant the privilege

to all the Roncalas

of nobility, and that the privileges

enjoy the rich-men;

And for further increase

whoever proves that he is the son

of a Roncalese, at the moment

be declared noble;

and as a shield I grant

to the valley the strong sword

for report of this fact;

and since Elvira cut off

the head of the proud king;

the Roncalas will always wear

will always wear a crown on their hair

a crown and even not...

To finish the play the king submission to Fortun to Elvira as wife and to Ordoño to Ximena.

The work is a hymn to the honor and defense of Gothic Spain against the Muslim invasion. It is impregnated with praise for the Catholicity of Spain and presents the king as the father of all Spaniards. But in addition to these very characteristic clichés of his time, there is also in the work a strong role for women. The main role of the play is not played by the Christian king, nor by any of his captains, but by Elvira, a woman of strong character, daughter of a Roncal captain. The role of Elvira is also accompanied by other women such as Ximena and Urraca. Elvira is the one who makes the most speeches in the play, speeches full of strength, boldness and resolution. She is the one who exalts the Christian king, makes the Moorish king fall in love, captivates Captain Fortun, organizes the women of Roncalese, convinces the men and the king to accompany them in the war, is appointed general of the Christian army, gives orders and organizes the military strategy and, finally, beheads King Abderramen. She is in the final the heroine of the comedy, but showing qualities that in the society of her time were reserved for men. Today we would describe this work as eminently feminist.

The author

The greatest connoisseur of the life of our author is Emilio Palacios Fernández. We follow his works (Fernández, El teatro popular español del siglo XVIII, 1998) (Fernández, Introducción a las Loas de Luis Antonio José Moncín Narciso, edition by Emilio Palacios Fernández) to outline a small review of the author of the comedy.

Luis Antonio José Moncín Narciso was born in Barcelona to a family of comedians; his father was a prompter in the theater and his mother a comedian. His brother Isidoro also worked in the theater as a prompter and was married to an actress (Cotarelo y Morin, 1899). The family moved to Madrid, where he married in 1756 with another actress daughter and sister of comedians, Victoria Ferrer (Cotarelo y Morin, 1899). Not finding employment in Madrid where his wife was already working, they had to go "by provinces". They worked in Granada and Cadiz, where our author began to gain reputation as an actor and playwright. He composed his first play in 1768. Given his growing fame, in the 1784-85 season he was called to Madrid, where he settled with his family. A sainete of the time describes his personality: "he is a man of good judgment", "his thinness, the austerity of his habits, that he is a smoker, that he owns a dog and a cat", "one with a very tight tie, a hat pulled down to his eyes, his size is a rod and average, and his hair is red... His body, although still very thin, his nose is outlined, he has the courage to want to be a poet and although his thoughts are loose, they are from graduate"(Cotarelo y Morin, 1899). Another description of his character is the one given by the director of the company in which he worked in 1788: "very quick to fulfill his obligation; a good man, and of good conduct; he has wit and composes comedies and sketches. He is married, and supports his wife's mother". Of his wife Victoria he comments that she is "outstanding. She plays the part without repugnance from the public. She is well behaved and married" (Fernández, Introduction to the Loas de Luis Antonio José Moncín Narciso, edition by Emilio Palacios Fernández). Luis Moncín retired as an actor in the 1791-92 season, which allowed him to increase his theatrical production considerably. He was one of the most prolix playwrights of his time, as 37 of his comedies have been catalogued subject: heroic, tragic, jocular, figurative, spectacular... But he also excelled in the production of short plays, very much in demand in his time, and 10 loas, 57 sainetes, 16 fines de fiesta, etc. are known to him. He has been considered the continuator of Ramón de la Cruz Cano y Olmedilla (brother of Juan, the famous engraver), the most famous sainetero from Madrid at the end of the 18th century. Luis Moncín died in Madrid in 1801. Palacios Fernández says of our author that "he complies with dignity with the codes of the drama of the popular theater that he has received and that he knows how to adapt to his time. He knows how to observe the tastes of the public and adapt his preferences. A partisan of the playful theater, more than the educational one, he does not forget some slight didactic touches. He had a loyal audience, even though some classicist newspapers made harsh censures of his premieres. The good reception of his plays allowed him to live with dignity" (Fernández, Introduction to the Loas de Luis Antonio José Moncín Narciso, edition by Emilio Palacios Fernández).

Music and dances

An important characteristic of Baroque theater was the inclusion of minor plays (loa, sainete, fin de fiesta, etc.) at the beginning, intermission and end of major plays (comedies, dramas, etc.). Another significant particularity was the inclusion in some parts of the play of music and/or dances, a characteristic that evolved giving rise to the appearance of a new theatrical genre: the zarzuela.

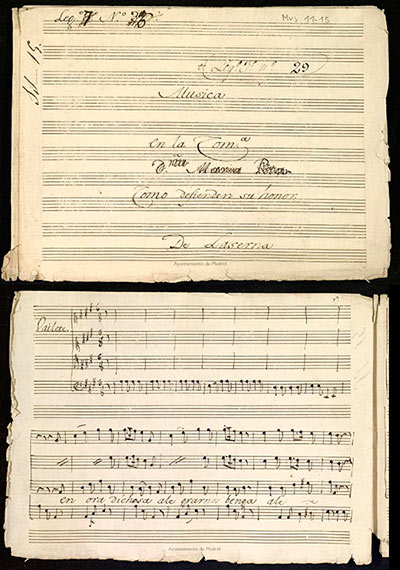

Our play, although I have not found it mentioned in any work, had music and dances at the beginning of the piece. As we have already seen above when detailing the first scene, the author describes that the actors receive the king "dancing a pastorela". In addition, the manuscript indicates as "music" the first stanzas of the play. But I have also located a score in the historical Library Services of Madrid (manuscript Mus 11.15), available on line, entitled "Cómo defienden su honor". It consists of 10 sheets of staves and the first sheet gives us the degree scroll of the work and the author (De Laserna). It is followed by two sheets initiated with the epigraph "bailete" (according to the RAE, short dance that used to be introduced in the representation of some theatrical plays) in which the first stanzas of the comedy are sung "En hora dichosa alegrarnos venga ale... nuestro rey Dn Sancho, triunfante en la guerra terror de los moros, de Aragón defensa, que vivía viva y triunfe, que reine y que venza que...". If we contrast it with the manuscript of the University of Seville, it is the same paragraph with which the work begins, appearing marked as "music". The remaining 8 leaves contain another bailete without lyrics, divided into parts for 1st and 2nd violin, 1st and 2nd oboe, and 1st and 2nd horn. This is the music with which the work we are studying begins, the music for two dances and a song with an orchestra of 2 violins, two oboes and two horns.

The author of the score is the Navarrese Blas De Laserna Nieva, who was born in Corella on February 4, 1751 and died in Madrid on July 8, 1816. He was probably the most important Spanish composer of music for theater in the last third of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century. He lived in Madrid, where he was a "company composer" and worked for the companies of the two Madrid theaters of the time: the Corral de Comedias del Príncipe and the Corral de Comedias de la Cruz. His work focused mainly on theatrical music, being one of the authors who most influenced the rise and splendor of a new theater-musical genre exclusive to Spain: the tonadilla escénica. More than 800 tonadillas of our author have been catalogued. He also composed 40 sainetes and more than 60 scores for comedies with lyrics by the main authors of the time, such as de la Cruz or Moncín. He is also the author of several operas, a zarzuela and a concerto for two horns. De Laserna can be considered one of the best Navarrese composers of the 18th century, together with Sebastián de Albero from Roncal.

Controversy with the Enlightenment

Our author had several polemics and was harshly criticized by the neoclassical writers of the Enlightenment. Neoclassicism was born in France in the mid-eighteenth century, with the intellectuals of the Enlightenment and as a reaction to the exaggerations of the Baroque turning his gaze to the ideals of Greek and Roman classicism, criticizing the customs and influencing the Education and morality. In the theater, the neoclassical rules demanded verisimilitude, unity of action, space and time, and to have a didactic and moral approach . As we have already seen, Moncín's play was harshly criticized at its premiere by the newspaper Memorial Literario, calling it "titerería e indecente" (Anonymous, Coliseo el Príncipe, company of Eusevio Rivera. Day 29 to June 3. Cómo defienden su honor las ilustres roncalesas: Comedia, 1784). The same year the polemicist and enlightened writer Juan Pablo Forner published another harsh criticism of the play: "not long ago a crazy comedy of Moncín was performed in which an army of Roncalesas rode out on horseback on mares in the sound of mojiganga to plot an obscenely ridiculous and outlandish stratagem against the Moors. I have never seen a greater set of delusions in my life" (Forner, 1847). The same thing happened at the premiere in Valladolid in 1788, the illustrated newspaper Diario Pinciano, published a review in which it said: "if we attend to what was represented, it was putting inside the forum a average dozen nonas of painted paper, which in two divisions passed successively to the view of the spectators, as it usually does in the royal machine or camera obscura ... Poor those who paid their money to see 'how the illustrious Roncalesas defend their honor' and found themselves with a magic lantern!"(Almuiña Fernández, 1974) The greatest exponent of Spanish neoclassical theater, Leandro Fernández de Moratín, was also encouraged to dedicate a poem mocking Moncín and the play we are commenting on (Moratín, 1840). It is a poem in which he lists the types of devils that exist and among them he mentions a devil that inspires the verses of the playwrights:

...of these devils that surround us,

there is another one angrier,

more insolent and kennel-like.

This is the one that inspires so many

verses of chain stitch,

and the one that gives to the theater

monsters instead of comedies.

...

He pointed to Valladares

his Lenten missions.

And to the miserable Moncín

his nefarious roncalesas...

So much ridicule received will make the play go down in the history of theater along with its author as one of the most criticized plays by the ilustrados (Cambronero, Los sainetes, 1895) (Cambronero, 1896).

bibliography

ALMUIÑA FERNÁNDEZ, C. Teatro y cultura en el Valladolid de la Ilustración: los medios de difusión en la segunda mitad del XVIII, 1974.

ANDIOC, R., & COULON, M. Cartelera teatral madrileña del siglo XVIII, (1708-1808), Anejos de Criticón 7. Toulouse, Presses universitaires du Mirail, 1996.

ANONYMOUS. Coliseo el Príncipe, company of Eusevio Rivera. Day 29 to June 3. How the illustrious Roncalesas defend their honor: Comedy. Memorial literario, instructivo y curioso de la Corte de Madrid, June 1784, pp. 111-113.

CABEZÓN, R. F. "La mujer guerrera en el teatro español de fines del siglo XVIII", yearbook de programs of study Filológicos, XXVI, 2003, pp. 117-136.

CAMBRONERO, C. "Los sainetes", Revista Contemporanea, 99, 1895, pp. 467-468.

CAMBRONERO, C. Revista Contemporanea, 104, 1896, p. 60.

COTARELO Y MORIN, E. Don Ramón de la Cruz y sus obras. essay biográfico y bibliográfico, Madrid, Madrid, 1899.

FERNÁNDEZ, E. P. El teatro popular español del siglo XVIII, Milenio, 1998.

FERNÁNDEZ, E. P. Introduction to the Loas de Luis Antonio José Moncín Narciso, edition by Emilio Palacios Fernández, n.d. Retrieved February 18, 2018, from http://betawebs.net/corpus-moncin/?q=node/68

FORNER, J. P. Revista Literaria de El Español, 1847, pp. 26-31.

IRVING A, L. "The Theater Season of 1791-1792 in Mexico City," The Hispanic American Historical Review, 31(2), 1951, pp. 349-364.

LEONARD, I. A. "La temporada teatral de 1792 en el Nuevo Coliseo de México", Nueva Revista de Philology Hispánica (4), 1951, pp. 394-410.

MONCÍN, L. Archive de la Universidad de Sevilla, n.d. Retrieved February 18, 2018, from Cómo defienden su honor las ilustres roncalesas: http://fondosdigitales.us.es/fondos/libros/5077/2/como-defienden-su-honor-las-ilustres-roncalesas/.

MONTOYA, C. P. Morir del teatro (II). Some plays performed in Havana during the 1790-91 season, n.d. Retrieved January 27, 2018, from http://librinsula.bnjm.cu/secciones/217/nombrar/217_nombrar_4.html.

MORATÍN, L. F. Obras dramáticas y líricas de D. Leandro Fernández de Moratín, entre los Arcades de Roma Inarco Celenio, Madrid, 1840.

PIÑAL, F. A. bibliography de autores españoles del siglo XVIII, Issue 5, Madrid, CSIC, 1981.

VIVEROS, G. "Un drama novohispano. La lealtad americana de Fernandez Gavila", Literatura Mexicana, VIII (2), 1997, pp. 695-779.