The piece of the month of November 2018

AS DELICIOUS AS IT IS CURATIVE: CHOCOLATE, THE DRINK OF THE 18TH CENTURY

report on the utilities of chocolate, a medical "paper" published in Pamplona in 1788.

Javier Itúrbide Díaz

PhD in History

The bibliographic heritage of Navarre reflects the changes and concerns that society has experienced in the political, scientific, cultural and religious spheres over the centuries. In this same space, "The piece of the month", in the article "La imprenta, tool del poder. The first printing of the royal oath (1586)", (2017, October), sample an early example of the use of the printing press by the political power, while in "Between the Renaissance and the Baroque: Ramillete de Nuestra Señora de Codés" (2016, October) a publication that manifests the pious exaltation of the Counter-Reformation is analyzed. Moving forward in time, on this occasion, a testimony of a medical publication in which the spirit of the Enlightenment is perceived is offered.

The printed

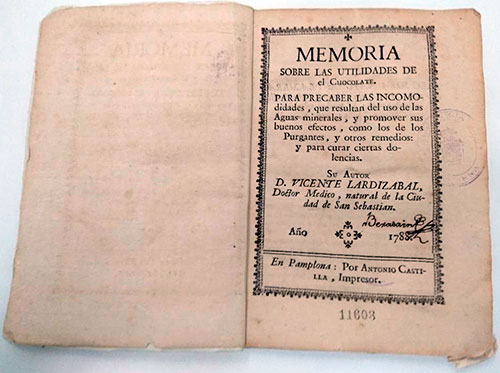

In 1788 appears in Pamplona the pamphlet report of the utilities of the chocolate to prevent the discomforts that result from the use of the mineral waters and promote its good effects, like those of the purgatives, and other remedies and to cure certain ailments. Its author is Vicente Lardizábal, who will also pay for the edition.

It is a quarto booklet (19x14 cm), consisting of three booklets of four sheets each, which are bound and sewn together. It is printed in one ink, as it was internship generalized for this subject of orders, and has 21 pages with text, duly numbered, although the composer has made a mistake and has assigned the last one the issue 31. In addition, each page has the corresponding claim that links with the first word of the following one.

The typesetter worked in a routine manner and did not stop to distribute the text of the original homogeneously over the 24 pages offered by the three booklets and, for this reason, he left the last three pages blank and wasted them, when, if he had taken care to distribute the text homogeneously over all the available pages, he would have obtained a cleaner composition, with more space for the headings of the paragraphs or sections and with more generous margins.

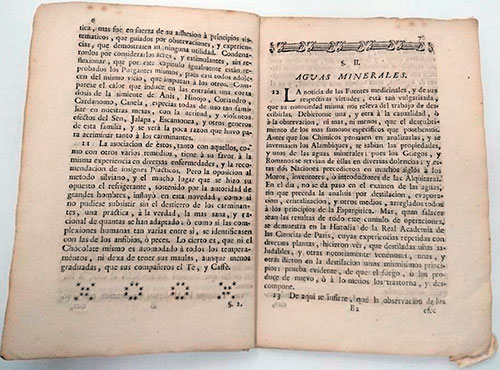

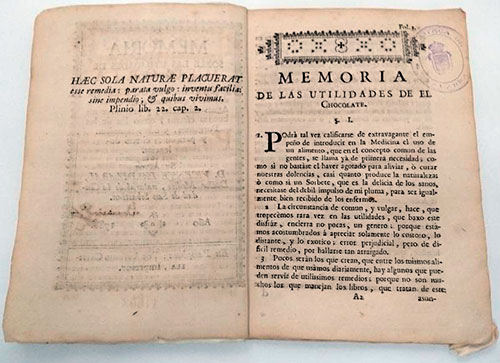

Despite these compositional deficiencies, it has good, clean type, good quality paper and correct printing, typical of an experienced workshop. The title page is decorated with a typographic border of plant motifs and is headed with a small cross, internship as secular as it is common in small works such as this one. The degree scroll, baroque in its extension and essay prolix, has been justified in a central axis. It is a somewhat archaic composition from the typographic point of view, if we bear in mind the date of its appearance, the end of the 18th century, and the roots that neoclassicism is taking in the printing presses. The interior ornamentation is as irrelevant as it is conventional, with capitals without ornamentation at the beginning of the three paragraphs into which the text is distributed, and head borders in the first two, while the third lacks borders and degree scroll. Also in terms of ornamentation, there is a certain incongruity on the part of the composer, since at the beginning and end of the first paragraph he uses routine typographic compositions, based on a border and small stars that form geometric figures, and to head the second section he resorts to a simpler and classicist xylographic block. The same can be said of the types used as headings for the first and second sections; in the first case, verses of three different bodies are used, the largest in bold, while the degree scroll of the second paragraph is resolved with italic verses, more in tune with the typographic tastes of the end of the 18th century. As has been pointed out, the third paragraph lacks degree scroll and the header border.

Finally, it should be noted that the first paragraph, "report of the utilities of chocolate", marked with Roman numerals like the following, occupies four pages (pp. 3-6); the second, "Mineral waters", five (7-11); and the third, which does not carry degree scroll and continues to deal with mineral waters, extends over ten pages (12-21). Following the internship of the time in scientific treatises, the paragraphs, in order to facilitate their identification and quotation, are numbered consecutively, from 1 to 50. This procedure had already been done by employee Lardizábal in two previously published books.

Library Services of Navarra.

Being a work of few pages, it lacks the legal and obligatory preliminaries in the books: licence, privilege and errata -the tax had been suppressed in 1762-. In all likelihood it is an edition at position of the author who would order a short print run, not for profit, to distribute it selectively. Significantly, the Catalog Colectivo del Patrimonio Bibliográfico Español only records four copies: in León, La Coruña and two in Pamplona.

The author

On the title page of the report Vicente Lardizábal "doctor doctor doctor, natural of the city of San Sebastián" appears as author. He was born in 1746 in the capital of Guipuzcoa, and was the only son of the marriage between Juan Bautista de Lardizábal and Manuela Dubois. The place where he studied is not known, although at a very young age, at 23 years old, he already qualified as "doctor of the city of San Sebastián" and at the same time he began to render his professional services in the Compañía Guipuzcoana de Caracas.

In connection with this position, in 1769 Lardizábal published in Madrid, where he was living at the time, his treatise Consideraciones político-médicas sobre la salud de los navegantes, in which the causes of the most frequent diseases, the way to prevent them and cure them are exposed, with the necessary instructions for the best regimen for the surgeons of ships that make voyages to America, especially for those of the Royal Guipuzcoan Company of Caracas, so that they may conduct themselves with greater success, both in the healing method of the sick, as well as in the management of the medicine cabinets of their position. It is a Issue in quarto (22x15cm), of 248 pages, correctly printed by Antonio Sanz, sold at the "bookshop de Hurtado de calle de las Carretas". It is striking that the author, a young man of 23, feels capable of tackling a large and complex topic like this one.

Three years later, in 1772, in the same printing house in Madrid, he printed Consuelo de navegantes en los estrechos conflictos de falta de ensaladas y otros víveres frescos en las largas navegaciones. resource easy to the use of sargazo or seaweed, a plant that reproduces naturally in the sea itself. dissertation This time the Issue is more humble, in octavo (17x10 cm), and has 238 pages, plus a correct intaglio engraving, folded, of the sargassum, which has copied the one published by the physician Cristobal de Acosta in 1578. If in the previous book the author was titled only "doctor of the city of San Sebastian", now he does so as "doctor of the Royal Guipuzcoan Company of Caracas in the city of San Sebastian". In this treatise he argues, without any foundation although supported by abundant contemporary bibliography , that the sargassum can be used as food for the crews and treatment against scurvy, which at that time constituted for them a threat as generalized as it was deadly. For all these reasons, Martí, the author's biographer, concludes: "Undoubtedly the contribution internship of Lardizábal's booklet must have been null".

A quarter of a century had passed since the publication of Consuelo de navegantes when Madrid saw the light, in 1798, of Flora peruviana, a work as rigorous as it was monumental on the botany of Peru and Chile signed by the prestigious scientist Hipólito Ruiz López. In this treatise Lardizábal's scanty rigor was criticized on having described the sargassum at the time that he was accused of plagiarizing what was published by Cristóbal Acosta two hundred years before. Lardizábal lacked time to publish, in the same year, an eight-page pamphlet, Reflexiones apologéticas, in which he assured that he had based himself on the contributions on scurvy of the Polish physician Johann Friedrich Bachstron (1688-1742) and that, when he wrote his book, 'not even for the life of him had he seen Acosta'.

Through his publications, Lardizábal is sample as a restless doctor, knowledgeable of the contemporary European bibliography , attentive observer of his environment and determined to disseminate his findings and knowledge, which would explain his entry in 1775 in the Sociedad Bascongada de Amigos del País, to which on different occasions he sends reviews of clinical cases that he has treated personally. He was also the author of several reports on the medicinal waters of Cestona, Erasun, Betelu and Belascoain.

When he enjoyed a consolidated and prestigious professional status , in 1776, at the age of 30, he married Manuela Ignacia de Sein, with whom he had three children.

He had inherited from his maternal family a forge in Goizueta, on the banks of the Urumea, in the municipality of Elama, where iron ore was extracted and smelted into ingots. This subject of factories needed a large amount of firewood, transformed into charcoal, to feed the smelting furnaces. Lardizábal's use of the surrounding beech and oak forests brought him into conflict with the town of Goizueta and the Collegiate Church of Roncesvalles, owner of the mountains adjoining the forge. All this led to a long, tangled and costly lawsuit, initiated in the Navarrese courts in 1762, which after four decades ruled in favor of Lardizábal and allowed the activity of the forge to reach the 19th century. The file General of Navarre keeps a dozen of thick files on this matter.

Lardizábal, undoubtedly on the occasion of his frequent visits to the courts of the Navarrese capital, delivered here to the printer his report on the utilities of chocolate, which saw the light of day in the workshop of Antonio Castilla in 1778.

Javier María Sada states that this same author "published a Catalog of the botanical species existing in the mountains of San Sebastián", of which not a single copy is known.

During the War of Independence, Lardizábal remains in his house in San Sebastián when the city is under the control of Napoleon's troops. In the final phase of the conflict, on August 31, 1813, the population is taken by the allied troops, commanded by Lord Wellington, who engage in looting, rape and arson. Among many others, Lardizábal's house will be assaulted and set on fire. For this reason he is forced to leave the city and to take refuge in his farmhouse of Larratxo, near Pasajes.

At this eventful juncture he publishes the Periódico de San Sebastián y de Pasages. The format is in octavo (20x9.5 cm), the usual format for periodicals of the time, and it has 30 cleanly printed pages without typographic ornaments. On the last page the date April 27, 1814 and, prominently, the name of the author: "D. Vizente de Lardizabal", without mentioning, exceptionally, the degree scroll "Doctor Médico". At the bottom of this same page, under a fillet, the imprint reads: "Tolosa de Guipuzcoa: en la imprenta de D. Juan Manuel de la Lama, año de 1814" (Tolosa de Guipuzcoa: in the printing house of D. Juan Manuel de la Lama, year of 1814). The restless Lardizábal, secluded in his farmhouse near San Sebastián, has the strength and peace of mind to write and order the printing of a "gazette or diary", as he calls it, of which he probably did not publish any more issues. Here, with some disorder, he gives an account of the "pestilent fever" spreading around him, describes its symptoms, resorts to the bibliography, provides historical news and describes his experience staff. Unexpectedly, he goes on to deal with bread, corn, sweet potatoes, bacon and hunting dogs, to end up abruptly returning to the subject of the plague whose origin he attributes to the "fear, sadness and terror" suffered by his countrymen because of the war and to whom, in order to recover their health, he proposes "courage and joy".

Four months after the appearance of his ephemeral "Periódico", on August 23rd, Vicente de Lardizábal died at the age of 68 in his refuge of Larratxo of a "putrid fever", leaving a widow and three children.

Foreign authors in the Navarrese printing industry

Vicente Lardizábal's link with Navarre, as has been explained, does not respond to his professional activity as a doctor but to the follow-up of the cumbersome lawsuit that he maintains in the courts of Pamplona related to the forge that he owns in Goizueta. Thus, it is possible to think that the order to print the report on the utilities of chocolate was made on the occasion of one of his frequent stays in the capital of Navarre, which would allow him to attend to his judicial affairs and also to correct the proofs of his printed work.

Of all the titles -some more than seven hundred- registered in Navarre's printing presses during the 18th century, the vast majority corresponded to Spanish authors -around 85%-, half of whom were born or settled in Navarre and the other half from abroad. The latter would be the case of Lardizábal.

thesis from report: the cure for the "staple foods".

In hisreport On chocolate, as he had already done in his two previous books, Lardizábal manifests himself as an empirical scientist, as a physician of the Age of Enlightenment, more confident in the observation of symptoms than in the authority of traditional authors: "I will always insist that, for the progress of Medicine, the observations made are the true light that must guide us". And in relation to the object of his work, he concludes: "The property that I attribute to chocolate is based less on conjectures of speech than on factual realities".

Like other physicians of the time, he believed that everyday foods could cure better than drugs by acting as "food remedies". This would be the case of wine, tobacco and chocolate, a "staple food" and fashionable drink in enlightened Europe, which was consumed diluted in milk or water, seasoned with cinnamon and sugar. Its presentation in tablet form became widespread in the 19th century.

To support his thesis on the primacy of the healing virtues of common foods over pharmaceuticals, he goes back to "Juan Cherino de Cuenca" -more precisely, Hernán Alonso Chirino (1365-1429)-, "physician to Don Juan Segundo, King of Castile", author of the Menor mal de la Medicina, of which he erroneously claims that it is an unpublished text, when it had been printed in Toledo in 1505. Chirino "reproves all purges composed of ingredients that at the same time are not nourishing" and, consequently, he confronts the medicine of his time that prescribed pharmaceutical potions.

His defense of healing by food is corroborated by the thesis of the "Polish physician" Augusto Quirico Rivino (1652-1725), who in his Centuria Médica advocated "food remedies for the cure of all kinds of diseases" and, consequently, rejected pharmaceuticals. Lardizábal argues that this theory, which had important followers, is still valid in his day "when aversion to officinal medicines is declared and [is advised] in persons of age or delicate complexion."

In this way, the author concludes that chocolate, "the delight of the healthy", by virtue of its therapeutic properties, is also "well received by the sick". On this occasion, as in the two books he had published, Lardizábal deals with a subject with which he was familiar due to his work relationship with the Compañía Guipuzcoana de Caracas, whose commercial activity was centered on the importation of cocoa.

For all these reasons, he proposes the employment of chocolate to attenuate the negative effects of treatments with purgatives and mineral waters, as well as to cure "certain ailments".

It is worth remembering that the insalubrity of the water, the bad state of the food and the poor hygiene staff caused, at the time, the multiplication of intestinal diseases and, to combat them, they resorted to purgatives of all kinds that, in the case of emetics, caused vomiting, and in the case of purgatives in the strict sense, stomach cramps. In either case the reactions could be very violent, to the point of endangering the life of the patients.

To corroborate his thesis , Lardizábal relies on Andrés Enoeffelio, "Polish doctor", for being the first who resorted to chocolate to "fix and modify the operation of purgatives", although he specifies that this treatment was known to him through a "captain of Spanish Guards who served in the wars in Italy".

In paragraph II of the report proposes the use of chocolate to "prevent discomfort resulting from the use of mineral waters", whether in beverages or in therapeutic baths.

To give greater solvency to his treatment quotation to the "famous author" Frederick Hoffman (1660-1742), physician and chemist, professor at the University of Halle in the Brandenburg Mark, who in his monumental Medicina rationalis systematica proposes the consumption of milk to counteract the negative effects of mineral waters used as purgatives, or also to associate it with them to improve their healthful effects. From here Lardizabal draws the idea of associating chocolate with medicinal waters: "The great analogy between Hoffmam's remedy and the one that makes the subject of this paper [he refers to his report]". And he concludes: "I do not doubt that if in the Mark of Bradenmbourg, where Hoffman practiced medicine, the use of chocolate had been as common as in Spain, this author would have used it as he used milk and would still give it preference in certain incidents and circumstances".

For all these reasons, he recommends taking chocolate before bathing or drinking medicinal waters, because in this way the stomach is "comforted", vomiting is avoided and its diuretic and laxative effect is increased. He admits that for the same purpose "broth, wine and other liquors" can also be useful, although less so, but warns that these do not encourage continuous drinking of water as chocolate does.

The report concludes with the accredited specialization of chocolate's ability to cure by itself "certain ailments", although he points out that he will not delve into this aspect because "this calls for more prolix discussion than fits within the narrow limits of this paper". He assures that it can be effective in combating phthisis and "certain class of atrophy or consumptions". However, he warns that these curative virtues have been attenuated to a great extent because the usual employment of chocolate has ended up making immune to those who consume it, since "even with poisons this happens, because it is constant that, if insensibly domesticated in our stomachs, they lose their deadly energy".

bibliography quoted by the author

To support his thesis Lardizábal relies on abundant bibliography, preferably foreign, and, above all, on his own medical experience. He only mentions two classics: Pliny, in the Latin quotation placed on the back cover -in the "exordium of this paper"-, and Virgil in the Georgics.

Regarding chocolate, he points out three basic monographs by Spanish authors: Primera parte de los problemas y secretos maravillosos de las Indias, by Juan de Cárdenas (Mexico, 1591); Diálogo entre un médico, un indio y un burgués, by Bartolomé Marradón (Seville, 1618); and Curioso tratado de la naturaleza y calidad del chocolate, by Antonio Colmenero de Ledesma (Madrid, 1631).

In addition, he shows that he is aware of foreign scientific publications, such as the certificate Eruditorum, a monthly magazine published in Leipzig between 1682 and 1782, which he will quote again in his Diario de San Sebastián and Pasages.

Medicine in the Navarrese editions of the Age of Enlightenment

Eighteenth-century editions in Navarre do not fully reflect the growing interest of the enlightened classes in scientific and philosophical matters. They only constitute approximately eight percent of the titles published, which represents the lowest percentage of the thematic classification corresponding to the Navarre books of the 18th century, below Literature, which reaches ten percent, and at an enormous distance from Religion, which accounts for 52 percent. This is corroborated by the fact that the thematic section of Sciences and Arts, quantitatively, is smaller than in previous centuries: 15 percent in the 16th century, 10 percent in the 17th century and, as has been said, 8 percent in the 18th century.

Of the more than seven hundred titles registered in the XVIII century, a little more than twenty are related to Medicine, Surgery and Pharmacy. Although interest in these subjects seems to increase as the century progresses, since twice as many titles are published in the second half of the century as in the first half. Within this subject , Surgery is the most numerous thematic group , among other reasons because its internship, requiring lower professional rank -usually corresponding to barbers-, was more widespread than Medicine and, in addition, in Pamplona the high school of surgeons of San Cosme and San Damián operated, whose students would demand manuals on the subject.

In 1748, the Pamplona pharmacist Martín José de Izuriaga published in four volumes, totaling two thousand pages, the well-known Surgery of Carlos Musitano, which he himself had translated from Latin. This is the first edition on Spanish of this work, which had been published in Geneva in 1716. The print run is 1,100 copies and the sale is at his own expense. It is undoubtedly a project publishing house of special relevance. Curiously, the medicine practiced by Musitano, and which Izuriaga supports, is galenic, which gives priority to pharmaceutical treatments over natural ones. It is therefore a thesis contrary to that maintained by Lardizábal.

Later, in 1766, Izuriaga will also translate and edit the treatise Universal Medicine or Treatise on the Origin of Diseases and the Use of Purgative Powders by Mr. Aylhaud. The French physician Jean d'Aylhaud (1674-1756) had achieved enormous fame and prosperity with his purgative powders that were prescribed to cure all subject of ailments. In relation to this controversial drug, years earlier, in 1750, the pamphlet enquiry política sobre crisis médica [...] was published on the powders of Aix in Provence. It was signed by graduate Juan de Zúñiga, who defended the curative virtues of Dr. Aylhaud's potion, and bore the imprint of Pamplona and the name of Juan Martí as typographer, a professional unknown in the capital of Navarre. It is possible to think that it was a fraudulent edition with origin in Castile published in the heat of the controversy raised by the mentioned drug.

The Examen nuevo de Cirugía Moderna, by the illustrated physician Martín Martínez (1684-1734), printed in Madrid repeatedly since its appearance in 1722, records four editions in Navarra, specifically in 1748, 1749, 1756 and 1766. At least this last one was fraudulent and would have been edited by the printer and bookseller Miguel Antonio Domech. To this same publisher would correspond the publication in Pamplona, in 1768, of the guide of the French doctor, settled in the Court of Madrid, Ricardo Le Preux (1665-1747), Doctrina moderna para los sangradores. It is a treatise, repeatedly published since its appearance in 1717, aimed at surgeons and dentists.

Among the few eighteenth-century Navarre editions of Medicine, the first Spanish edition, printed by Pascual Ibáñez in 1773, of notice al pueblo sobre su salud, by the Swiss physician Tissot (1728-1797), a disseminator of public hygiene and healthy practices of enormous success throughout Europe, stands out. Lardizábal quotation him in his "paper" to purpose of the cure with chocolate of a "hectic" child, evicted by the doctors.

In Pamplona, in 1734 and 1738, the first two titles of the critical-medical Palestra of the Cistercian monastery of Veruela Antonio José Rodríguez (1703-1777) were published, while the remaining four were printed in Zaragoza and Madrid. The author, as Vicente Lardizábal would advocate half a century later, bases his knowledge and treatments on experience, while relegating theories based on tradition. This fundamentally empirical approach brought him the civil service examination of a considerable sector of official medicine.

In the section of Pharmacy, the figure of the Pamplona apothecary Pedro Viñaburu stands out, who published in 1729 his Cartilla pharmaceutica, chimico-galenica in which he deals with the ten considerations of the canons of Mesue and some chemical definitions for the utility of the youth. Years later, in 1778, his son Joaquín, who attended the apothecary's shop opened by his father in Zapatería Street, would republish it. As announced in the degree scroll, it is a work for students that summarizes the most traditional pharmacopoeia, still subordinated to medieval authors such as Mesué the Younger, who died in Cairo in 1015.

The first edition of Viñaburu's Cartilla pharmaceutica was viciously refuted, in 1738, in the anonymous pamphlet Compendio breve muy util y necessario para todos los professores de la medicina, which denounced "the imaginary fallacious rules of the canons of Mesué" advocated by the pharmacist of the Navarrese capital, whom the author of the pamphlet considered "as ignorant as he was presumptuous".

The Heirs of Martinez got part of the print run of the famous throughout the continent Batean Pharmacopeia of George Bate (1608-1669), belonging to the Portuguese edition of Luis Secco y Ferreira, and marketed it as their own by including on the original cover by way of a clearly false imprint: "Pamplona. By the Herederos de Martínez and at his own expense. Year 1763".

The treatment of illnesses based on medicinal waters, studied by Lardizábal in his reportThe treatment of illnesses based on medicinal waters, studied by Lardizábal in his work, acquired special relevance in the 18th century, as can be seen in the publication of abundant works on their composition and curative virtues. Manuel Rodrigo y Andueza, doctor of the General Hospital of Pamplona, publishes the Book of the prodigious baths of Thyermas. In which some of the most celebrated baths of Spain, France, Germany and Italy are epilogued. It saw the light in 1713, in the workshop of Juan José Ezquerro, with a print run of one thousand copies. For his part, Antonio Ramirez, at the time doctor of Fitero and its monastery, is the author of a monograph, published in 1768, on the virtues of the thermal waters of this locality and dedicates it to his best known son, "el Excelentissimo, Ilustrissimo y Venerable Señor Don Juan de Palafox y Mendoza". Twenty years later, when he practices in Viana and is a member of the Real Academia Médica Matritense, to which also Lardizábal belonged, he takes to the printing the report and analytical examination of the mineral waters (called vulgarly, though with impropriety, acidulas) of the source of Calderin in the town of Lodosa.

As an anticipation to the thesis of Lardizábal on the cure with common remedies, in 1754 it is published in Pamplona El medico de si mismo. Modo practico de curar toda dolencia con el vario i admirable uso de el agua, that, under the pseudonym of the doctor Don Joseph Ignacio Carballo de Castro, the friar Vicente Ferrer Gorraiz y Beaumont has written. This work, of little more than one hundred pages, was published at the same time in Madrid and Barcelona, which test the interest it aroused.

Thus, the pamphlet published by Vicente Lardizábal on the therapeutic effects of chocolate is part of a group of Navarre editions related to health that, although not relevant because of its issue , can be relevant because of the dissemination of works known in Europe, either specialized, such as those of Carlo Musitano and George Bate, or from knowledge dissemination , such as Tissot's work. To these foreign titles would be added those of Navarrese authors, such as Antonio Ramírez, Manuel Rodrigo y Andueza, and Pedro Viñaburu.

Chocolate, apart from its therapeutic dimension, from the beginning of its diffusion in Europe in the 16th century, raised an intricate controversy among moralists, who elucidated whether its consumption broke the ecclesiastical fast. To this discussion was added, in 1754, the Carmelite of the convent of Tudela, José Vicente Díaz Bravo, with El ayuno reformado, a volume of more than four hundred pages in quarto that included a "dissertacion historica, medico-chymica, physico-moral de el chocolate y su uso" (historical, medico-chymical, physico-moral dissertation on chocolate and its use).

The printer

When Vicente Lardizábal, on the occasion of one of his stays in Pamplona, decides to contract the printing of his report on the utilities of chocolate, there are six workshops in the Navarrese capital, which is the highest issue since the introduction of printing in the sixteenth century.

The author chooses a printing house in Pamplona despite the fact that in San Sebastian, where he usually resides, the workshop of Lorenzo Riesgo, printer of the Juntas Generales de Guipúzcoa and of the Compañía Guipuzcoana de Caracas had been in operation for a couple of decades; by the way, he was the grandson of the Navarrese printer Juan José Ezquerro (ca. 1670-1727).

Returning to the printing presses of Pamplona, two were of recent creation: those of José Longás (active between 1774-1795) and Benito Cosculluela (1775-1794); both were established on their own when in 1770 their patron saint, Miguel Antonio Domech, enriched by other activities, closed the workshop. The remaining four had a solid trajectory throughout the century: Joaquín Domingo (1775-1800), José Francisco Rada (1787-1800), María Ramona Echeverz, widow of José Miguel Ezquerro (1784-1808), and Antonio Castilla (1757-1791). The latter was the oldest, having been at the head of his workshop for 29 years, and he was the longest-serving director of a Pamplona printing press in the 18th century.

Antonio Castilla's workshop offers a low profile typical of a small printing business and bookshop, although stable, with a very small staff, which undertakes modest commissions and, for this reason, is not in conflict with his colleagues for whom it is not a significant competitor. Thirty-five percent of his books are of good or excellent quality, making him in tenth place among his Pamplona colleagues of the eighteenth century.

The Jesuits of the capital of Navarre were regular customers until their expulsion in 1767: they ordered large print runs of catechisms and devotional books in Basque that they distributed in their missions in Basque-speaking towns. These works accounted for forty percent of his book production. Antonio Castilla, who was born in Pamplona, in all probability spoke Basque, while composing works in Latin and, of course, in Spanish.

As is well known, the work of the printing presses of the time corresponded mostly to small orders, such as Vicente Lardizábal's pamphlet. In this sense, Antonio Castilla's printing house printed average one book a year, while his colleague José Francisco Rada printed twice as many. Precisely between 1785 and 1788, the period in which the report on the utilities of chocolate saw the light of day, is when his activity intensified with two titles a year. Thus, in the same year in which he printed the aforementioned report he also published Controversia moral, in a 244-page quarto Issue that the parish priest of Larraya, Juan José de Erice, had written on private oratories, and Thelogicum competition, a modest 80-page volume in quarto with an abstruse speech by the Mercedarian Raimundo de Zala.

From the wide range of books and pamphlets published in Pamplona throughout the Age of Enlightenment, on this occasion we have chosen report on the utilities of chocolate, a modest medical "paper", written and published by a well-known foreign professional, with business and lawsuits in Navarra, which somehow reflects the spirit of the time: empiricism, rejection of traditional formulas, a certain scientific frivolity, cosmopolitanism, and the philanthropic commitment to improve public health as a requirement to achieve the happiness of the people.

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND ELECTRONIC RESOURCES

ITÚRBIDE DÍAZ, J. Los libros de un Reino: Historia de la edición en Navarra (1490-1841). Pamplona, Government of Navarra, 2015.

MARTÍN LLORET, J. B. Vicente Lardizábal. Doctor from San Sebastian during the Enlightenment. San Sebastián, Diputación Provincial de Guipúzcoa, 1970.

SADA, J. M. Historia de la ciudad de San Sebastián a través de sus personajes. Irún, Alberdania, 2002. The digital edition is available in Google Books.

LARDIZÁBAL, V. Consideraciones político-médicas sobre la salud de los navegantes, Madrid, Antonio Sanz, 1769. available on Google Books.

LARDIZÁBAL, V. Consuelo de Navegantes. Madrid, Antonio Sanz, 1772. available on Google Books.

LARDIZÁBAL, V. report sobre las utilidades del chocolate, Pamplona, Antonio Castilla, 1788. available at Library Services Navarra Digital (BiNaDi).

LARDIZÁBAL, V.Reflexiones del doctor Vicente Lardizábal [...] sobre algunas expresiones que don Hipólito Ruiz, Primer Botánico de la Expedición Peruviana, ha estampado en su Comentario de la fructificación del sargazo. Barcelona, Francisco Suriá y Burgada, 1798. available at Library Services Digital. Royal Botanical Garden. CSIC.

LARDIZÁBAL, V. Newspaper of San Sebastián and Pasages. Tolosa, Juan Manuel de la Lama, 1814. available in the Library Services Digital of Koldo Mitxelena Kulturunea.