The piece of the month of October 2018

KERREN BILDUMA. ROTISSERIES AT THE ETHNOGRAPHIC MUSEUM OF THE KINGDOM OF PAMPLONA (ARTETA)

Mª Gabriela Torres Olleta

GRISO University of Navarra

Santiago Rusiñol confessed in "My old irons" (article published in La Vanguardia on 22-1-1893) that "the mania for owning and collecting antiques is an incurable illness". Thanks to this illness, which undoubtedly also afflicted the Navarrese sculptor Ulibarrena, a collection of rotisseries is kept in the Arteta Museum, which I will deal with in this piece of the month without intending to be exhaustive and as an invitation to get to know it.

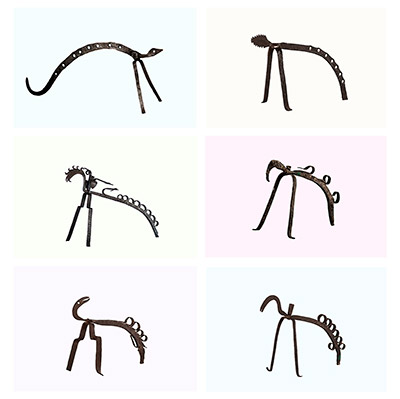

They are anonymous pieces forged in iron by craftsmen, of different sizes and quality, some rougher, others very elaborate, all marked by use and time, and of unquestionable formal elegance and beauty.

These wrought-iron spits consist of three parts: the spit or 'skewer' on which the piece to be roasted is threaded, and two supports, one next to the handle of the spit which allows it to turn, and another, more important from an aesthetic point of view, known as the 'cock', 'donkey' or 'ass', whose shape resembles that of a stylised animal, whose sloping back has several holes or scrolls where the tip of the spit rests, graduating to the desired height. The ornamentation is concentrated in this part (although geometric ornamentation can be seen on some spikes).

These supports resemble the silhouettes of imaginary, gigantic dragons or serpents with their backs crowned by a fabulous crest. Depending on the imagination of the observer and the fantasy of the creator, the profile of a cockerel with its crest or the back of a long-suffering donkey bearing the burden can also be seen in their designs. In all cases they are topped by fantastic heads, evidencing in these creations the desire to add an aesthetic dimension to a practical everyday object, which is also evident in the numerous variations on the common basic model .

Arteta's collection consists of around thirty pieces, including "donkeys" and "spikes", of different sizes and in different states of preservation Degree . In Ulibarrena's own words:

We have a very varied collection of 29 examples, classified from the 15th to the 19th century, all of which are forged and made with a great sense of ethnic and plastic expression. They come from the Valley of Odieta, Baztán, Larráun, Burunda, Ronkal, Orba, Ansoain, Esteríbar, Juslapeña (all in Nabarra). Some others come from leave Nabarra, Zuberoa, Guipúzkoa, Jacetania and Aragón. Legends and myths are attributed to these sculptures, of fantastic forged fauna, and they are of great plastic expression (p. 32).

In the two fundamental pieces (the spike and the cockerel), the form corresponds to the function they perform, with the addition of the decoration, which in turn manifests a wealth of cultural forms that are at least pan-European, involving both the craftsman who tames the iron and the individual who commissions and uses the work.

These forms are made up of dreamlike evocations, uncertain figures from legends and mythologies that the "lord of fire" with his technique transfers to the material and whose result, the rotisserie, is a functional and aesthetic piece, similar to what happens with other household pieces, such as the baroque morillos described by Fernando de Olaguer-Feliú (p. 236) when he recalls that "in the 17th century they were again forged entirely in iron, generally lacking the bronze applications of the Renaissance and sporting the fundamental and almost constant ornamentation of the so-called 'iron'. 236) when he recalls that "in the 17th century they were again forged entirely in iron, generally lacking the bronze applications of the Renaissance and sporting as a fundamental and almost constant ornament the so-called chimerical heads, animal shapes with the appearance of dragon heads, emerging from a long neck and open jaws from which protrude curled up language, in simulation of monsters of legend vomiting fire".

It should be pointed out that the personification of animals that symbolise both the evils or dangers that threaten man and embody the mythological beings that can protect them from them, is, according to anthropologists, a constant feature since the origin of mankind. Caro Baroja in La casa en Navarra ( p. 16) points out, for example, that the zoomorphic figures that crown the hooks of the Basque llares seem to have a protective significance.

Examination of the rotisseries reveals differences in the size and shape of the back, heads and legs. There are specimens that are carried on the back:

Two or three scrolls:

Four scrolls, five and up to ten.

Volutes on back only or on back and underside:

Other times the body of the donkey is decorated with different shaped holes issue . The Arteta Museum exhibits rotisseries:

With one, four, five, seven or eight holes:

In some cases, holes and scrolls or rings, closed or open, are combined:

As for the heads, there is a great variety that expresses the creativity of each craftsman, with a certain frequency of monstrous shapes that imitate snakes, dragons or birds, without lacking plant figures and Structures more abstract ones such as spirals or other geometric shapes. Arteta's collection includes:

Of a snake with an eye and a mouth that turns its head in a threatening gesture:

Of snake or bird without mouth or eye, only the silhouette:

Hook-shaped or serrated or saw-shaped:

A beautiful one in the shape of a rolled-up ribbon and a very original one with a twisted and folded rod:

Undoubtedly the most spectacular head is that of a magnificent Roncalese dragon in which organic forms of animal and plant merge.

Other parts of the animal shapes are the legs and the tail, where the same variety of possibilities is sample , with single or forked tails, with one-piece curved or two-piece riveted legs, which can end straight or with a rounded turn.

The attachment of the legs to the back also takes different forms. The most striking is the case of protruding shanks with ornaments.

Anyone interested in subject can compare the rich collection of the Ethnographic Museum of the Kingdom of Pamplona with other specimens kept in other museums. Among them is the one from San Telmo de San Sebastián (inventory no. E-001547), which comes from the Urdaneta de Legorreta farmhouse in Guipúzcoa, which the inventory card defines as a curved bar with a rectangular cross-section and circular holes. It rests on two parallel feet and is topped with a bird-shaped head. This common item of household furnishings is known as an "oilarra" (cockerel) because of the way it usually looks.

The same museum has another one from the beginning of the 20th century, from Saldías, Navarre (inventory E-001557), which has an original wheel on the main support that facilitates the turning of the spit.

A third corresponds to inventory card E 001558.

In the Euskal Museoa of Bilbao there is another spit, probably from the 19th century, made of wrought iron, consisting of a rod or spit, which has a tripod next to the handle and the support called "rooster" or "donkey" with scrolls that create the spaces where the tip of the spit rests, graduating to the desired height. According to Catalog, "it comes from the Ciria house in Estella, Navarra, where it arrived, around 1965, from a farmhouse on the slopes of Aralar".

To these Navarrese specimens we can add the one in the Museo Etnológico Caro Baroja in Estella, from the collection of Francisco Javier Beúnza. Juan Cruz Labeaga quotation in a documented article in which he includes a drawing (p. 123), and in which he mentions an inventory from 1595 in the house of Juan de Vera in Sangüesa that includes an "asnico de fierro para asar", another inventory from 1600 by Remón de Liédena which includes "un asnico para el fuego", and a third from 1621 by Ambrosio Pérez de Veráiz, who owned "un asnillo de hierro para asar".

The extension of this object in the Pyrenean area is confirmed by others like the one in the Ángel Orensanz y Artes de Serrablo Museum, which has two specimens (inventory numbers 01462 and 01463), or the one in the Ethnological Museum of Zaragoza Casa Ansotana, where there is a "morillo in the shape of an animal" that comes from Ansó, Huesca (fig. 54 of Museo de Zaragoza. Section of ethnology), but it is also known in other areas. In the card of Catalog of the piece conserved in the Museo del Traje of Madrid, research center of the Ethnological Patrimony, (issue of inventory CE 004264) it is commented:

the creation of these curious pieces, forged with three feet and whose heads are often reminiscent of the stylised figure of a cockerel, a dog or a horse, was very popular in Extremadura, a region with a strong rural tradition of blacksmithing characterised by the use of curly iron in its creations. employment . The production of these cocks has been documented in Spain since the 12th century.

Beautiful is the one in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, a 17th century piece of probably Catalan origin.

Documented, as we have seen, since the 12th century and in use until a few decades ago, these rotisseries typical of the rural environment seem to have been especially frequent in the Pyrenean or pre-Pyrenean cornice, without it being said that their use has been exclusive to this area, where the forms and ornamentation of the roosters have remained alive for a longer period of time. Paraphrasing Gombrich(The Sense of Order, p. 210), it could be said that in these rural communities there is a special "tenacity of decorative traditions", which is characteristic of small, enclosed villages where the traditional way of life endures.

In the group of rotisseries that I have mentioned, the Arteta museum has the largest number of rotisseries and is an exceptional case in terms of quantity, quality and heritage value.

The cultural significance of this heritage is not limited to the poor definition of the academic dictionary (craftsman: "person who exercises a purely mechanical art or official document "), but responds better to the enlightening and suggestive words of Gombrich (p. 11) when he writes: "the work of the master craftsman proceeds with a constant rhythm as his hands move in unison with his breathing and perhaps with the beating of his heart". Heart and beats that we know are unique to each person and that in the case we are dealing with could well mark the rhythmic beating of the forge.

Objects and forms that arose to respond to two needs: the domestic one around the family and community home (as the size of some rotisseries points to a festive meal, not just a family meal) and the aesthetic concern.

Magic and mystery, chimeras, nobility, iron and fire, food, home and celebration are some of the evocations that these old irons transmit to us.

It is our obligation to value and conserve this heritage, especially that of our surroundings, and to be grateful for the pleasure of enjoying it in museums such as the Ethnographic Museum of the Kingdom of Pamplona in Arteta.

Photographs Salvador Arellano

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

BELTRÁN LLORIS, M. and MARTÍNEZ LATRE, C. (coords.), Museo de Zaragoza. Sección de etnología, Zaragoza, Gobierno de Aragón, 2010.

BONET CORREA, A. (coord.), Historia de las artes aplicadas e industriales en España, Madrid, Chair, 1994.

CARO BAROJA, J., La casa en Navarra, Pamplona, Caja de Ahorros de Navarra, 1982, t. II.

GOMBRICH, E. H., El sentido del orden. Estudio sobre la psicología de las artes decorativas, Madrid, discussion, 1999.

LABEAGA, J. C., "Artesanos y artesanía del hierro en Sangüesa", Cuadernos de etnología y etnografía de Navarra, year 26, no. 63, 1994, pp. 59-164.

OLAGUER-FELIÚ, F., "Objetos metálicos", Historia de las artes aplicadas e industriales en España, Madrid, Chair, 1994, pp. 217-242.

RUSIÑOL, S., "Mis hierros viejos", 22-1-1893, La Vanguardia.

ULIBARRENA, J., Ethnographic Museum of the Kingdom of Pamplona, Pamplona, 1990.