The piece of the month of September 2018

THE MANNERIST CANVAS OF SAN MIGUEL DE CÁSEDA (1601) AND ITS GRAPHIC SOURCES

Pedro Luis Echeverría Goñi

University of the Basque Country

The collateral altarpiece of San Miguel de Cáseda serves as framework for the Mannerist altar painting of the Archangel expelling Lucifer and the rebellious angels, by Juan de Landa. Although Casado Alcalde dated this and the collateral of Santa Catalina with its paintings between 1607 and 1613, by a later account inquiry we must advance its chronology to 1601. An elderly Joan de Cisneros, who was for several years mayor, alderman, primiciero and other positions in the town, declares in some evidence of 1661 that "two golden coraterals were brought for the parish church of the said town, maybe sixty years ago, a little more or less". This date practically coincides with that given by Ceán Bermúdez, who was the first to document this work in his 1800 Dictionary. The payments were made in bushels of primitive wheat and in 1604 or 1605 the painter assigned some amounts owed to him by the administrators to graduate Pedro de Güesa, beneficiary of the church, which should have been paid by the primitiaries in land and vineyards. The presence of a canvas on panel of this size in the early 1600's, a combination that Juan de Lumbier would repeat later on, is early and novel.

J. de Landa. Canvas of St. Michael expelling the devil and the rebellious angels.

Collateral altarpiece. Parish of Cáseda.

The apocalyptic topic of the combat of St. Michael and his angels against the Devil or Satan, denomination of the great dragon or ancient serpent, and the rebellious angels who were cast to the earth was adopted in the Counter-Reformation as one of the psychomachies that best expressed the triumph of the orthodoxy of the Catholic Church against heresies and, more specifically, against Protestantism. As the prince of the heavenly militia, he is depicted here as a young, blond boy, with the anatomical armor and the Roman coat of arms, though without a helmet. The flaming sword of the archangel is transmuted in this case into the flame of fire that he wields in his right hand as an instrument of divine wrath in the manner of the Jupiterian beam of lightning.

This "historia grande" is a Mannerist oil painting in which the influence of Michelangelo in type, anatomical exaltation and foreshortening is clearly visible. The stays of Juan de Landa y Gulina (+ 1613) in Flanders, which we document, and especially in El Escorial, allowed him to learn first-hand about Venetian painting and the work of Italian masters such as Tibaldi and, through them, the Florentine genius. This is the origin of the colorful palette of this canvas with bright contrasts of blues, reds and yellows. We also notice in this work programs of study pretenebristas light with a radical contrast between the sky, represented in the upper register by a golden glow, and the "earth", embodied by the darkness in which the demons writhe. These realms are the moralization of a painting that represents the triumph of light over darkness. The upper register anticipates the angelic glories of the Baroque, while the lower register is a Mannerist work whose characters derive, ultimately written request, from the devils and damned of the Last Judgment and other figures painted in the Sistine by Michelangelo.

The archangel sample in his flight is one of the Michelangelesque contrapositions with his arms open to his right and his head and legs turned to his left. The dynamism implicit in this scene and in the energetic gesture of St. Michael is manifested in the cape, the skirt and the flying leather strips, as well as in the lines of force of the painting, which describe a game of broken diagonals in mannerist zigzags that will pass into the Baroque. He is flanked by three corporeal angels in elaborate postures, while in the background the heads of winged cherubs are blurred. Submerged in the lower part of the painting, four figures stand out in the shadows, of which the darkest incarnation of Lucifer stands out, with satyr-like features, such as pointed ears, hooked nose, horns, tail and bat wings. The other three fallen angels are anthropomorphic figures with impossible foreshortenings, which derive from Michelangelesque prototypes of the Sistine Chapel, such as the figure facing the devil, inspired by the Adam of the Creation scene.

A composition as brilliant as this one by Cáseda will allow us to investigate his graphic sources and establish a model pathway of images that make explicit the fortune of Landa's painting. We know that he copied Flemish engravings by C. Cort or A. Sadeler from Venetian creations by F. Zuccaro or J. Palma. This Mannerist iconography has its origin in the Great St. Michael striking down the devil that Raphael painted in 1518, a work very diffused in engravings and drawings. We can consider as an intermediate milestone the archangel St. Michael unsheathing the sword, painted in 1547 in the Paolina chapel of the Castello de Sant Angelo, by Pellegrino Tibaldi, rather than the painting he did in 1592 in El Escorial. In general lines, the fluttering of the archangel is similar to what we see in a drawing by Jacopo Palma the Younger that represents St. Michael and Lucifer. We must emphasize that this outstanding Venetian painter and draughtsman, with a production characterized by the synthesis of influences of the great Florentine and Venetian Renaissance, is the inventor of works that Juan de Landa will copy, such as the Flagellation of Sagaseta, the Holy Burial of Tafalla or the San Sebastian of Cáseda.

J. Palma the Younger. Saint Michael and Lucifer. The British Museum.

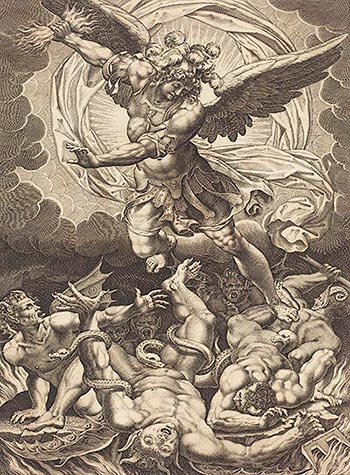

However, the coincidence of our Saint Michael is total with two later prints by Philippe Thomassin that surely refer us to a common earlier model that is repeated in the Navarre painting, perhaps the earliest he made of the archangel in 1588. The first is located in one of the plates of the spectacular Fall of the rebel angels of 1611, made from a creation of Giovanni Battista Ricci of Novara. The identity is more complete with that of the Fall of the rebel angels, dated 1618, with very similar foreshortenings of the saint and the demons.

P. Thomassin. The Fall of the Rebel Angels. National Gallery of Art, Washington.

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

file Diocesan of Pamplona, Oteiza, C/1079, no. 1.

CASADO ALCALDE, E., La Pintura en Navarra en el último tercio del siglo XVI, Pamplona, Príncipe de Viana, 1976, pp. 113-115.

CEÁN BERMÚDEZ, J. A., Diccionario histórico de los más ilustres profesores de las Bellas Artes en España, t. III, Madrid, Real Academia de San Fernando, 1800, p. 3. Facsimile edition, 1965. Madrid, Akal, 2001.

ECHEVERRÍA GOÑI, P. L., "Pintura", R. FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA (coord.) and others, El arte del Renacimiento en Navarra, Pamplona, Gobierno de Navarra, 2005, pp. 319-323.

GARCÍA FRÍAS CHECA, C., "Pellegrino Pellegrini, Il Tibaldi (1527-1597) y su fortuna escurialense", J. L. COLOMER and A. SERRA DESFILSA, España y Bolonia: siete siglos de relaciones artísticas y culturales, Madrid, Centro de programs of study Europa Hispania, 2006, p. 130.