The piece of the month of December 2019

THE MISSALE TIRASONENSIS (1500) AND THE MISSALE PAMPILONENSIS (CA. 1501) PRINTED IN PAMPLONA BY ARNAO GUILLÉN DE BROCAR

Javier Itúrbide Díaz

PhD in History

The first two books with musical writing

In the last year of the incunabulum period, in 1500, the missal of the diocese of Tarazona - MissaleTirasonensis, as the colophon reads - was published in Pamplona. This subject of books contains the sacred texts that are read at masses throughout the year, the liturgical instructions to be followed by the officiant and the chants for the most important feasts, such as the Holy Week offices. For this reason, the Missal Tirasonensis includes musical compositions; this is important because the printing of musical pieces requires the use of special typefaces, which are much more numerous and more difficult to compose than those used for the texts.

Then, around 1501, at the beginning of what has come to be known as the postincunabulum period, which in Spain conventionally ended in 1520, the printing house in the capital of Navarre brought out a new missal, in this case for the diocese of Pamplona - MissalePampilonensis reads the Incipit -which also contains liturgical music.

They are the first publications of the Navarrese printing press with musical notation and show that at the beginning of the typographic art it enjoyed a high level of quality.

The Church was one of the main promoters of printing from the earliest days of its appearance. Until that time, manuscript books had been used to systematise the liturgy, the production of which, as is well known, required specialised staff and took a long time, which is why they were as scarce as they were expensive.

In terms of their formal appearance, incunabula did not seek to break with the patterns of the codices, but rather to repeat their characteristics as luxury objects with the important difference that their price was much lower. For this reason, they reproduced the format, the staining of the page in which two columns of text predominate, the repeated use of letter ligatures and word abbreviations, the wide margins, the signaturisation of the sheets, the distinction of the text by means of black and red inks, the ornamentation of the initials - "capletrado"- and, where appropriate, the musical notation; copies were even printed on vellum if they were intended to offer a particularly luxurious print run.

When the printing press made it possible to multiply the number of copies - it is estimated that the print runs of incunabula ranged from three to six hundred copies - at lower costs, it became possible to disseminate sacred and liturgical texts. test This is why one of the first Gutenberg editions, dated around 1456, is precisely the Bible - known as the Mazarine or 42-line Bible - and that among the most frequent titles are those intended for the liturgy, in which, as mentioned above, it was essential to include the chants of the Mass.

Thus, among the first printed works with musical figures are the Psalterium Benedictinum, printed in Mainz in 1459, and the Constance Gradual, dated 1473. As for missals such as those discussed here, the first work printed by Gutenberg was the Constance Missal, dated around 1450. From this time onwards, the dioceses of Christendom endeavoured to publish their own missals, in which they included their own liturgical peculiarities. The first to be published in Spain was the Missale Cesaraugustanum, which the renowned German printer Pablo Hurus finished printing in Saragossa on 27 October 1485. The printing of the missals of the dioceses of Tarazona and Pamplona in the capital of Navarre is part of this chronological line of the spread of printing and liturgical books. But who was the printer and why in Pamplona?

The printer and his environment

Arnao Guillén de Brocar printed the missals of Tarazona and Pamplona around 1500. For the last decade he has had a printing workshop in the capital of the Kingdom of Navarre, where he had arrived, possibly called by the cathedral chapter, as his first known work is the Manuale secundum consuetudinem ecclesiae Pampilonensis, which came out on 15 December 1490, as stated in the colophon.

It was 40 years since the printing press had emerged in Mainz and 18 years since its arrival in Spain, the first manifestation of which took place in Segovia, at the hands of the German Juan Párix, with the printing of the conference proceedings of the synod held in Aguilafuente in 1472. From there it spread with surprising speed: Barcelona and Valencia (1473), Zaragoza, Guadalajara, Tortosa, Lérida, Salamanca, Murcia, Murcia, Toledo, Seville, Zamora, Huete, Tarragona, Burgos, Palma de Mallorca, Valldemosa, Híjar and, finally, Pamplona.

Brocar, the first printer in Navarre, is a relatively young Frenchman, possibly from the area of Orthez, in the viscounty of Bearn, which at that time was linked to the crown of Navarre. He must have trained professionally in Toulouse, where typographers of recognised prestige worked.

At this time, the printing business was uncertain, printers went in search of contracts and set up their workshop where they received them and continued on the spot as long as they had work guaranteed. They were nomads, and this must have been the case with Brocar.

He lived in Pamplona for a decade, from 1490 to 1501, and during this time he worked hard and well. He served not only his immediate surroundings, but also more distant markets such as Lugo, Mondoñedo, Burgos, Zaragoza, Calahorra, El Burgo de Osma, Tarazona and Lescar.

He is known to have printed at least 25 books, as well as smaller works such as printed bulls and indulgences that reached large print runs. As was usual at this time and in the following centuries, the Church was his main client; thus, of the 25 works, 17 are of religious content, mainly liturgical.

Backed up by the constant stream of commissions, Brocar established himself in Pamplona and married a neighbour of the city, María de Zozaya, with whom he had three children: Juan, Pedro and María. However, times were not good for business, as the political climate was unsure; Queen Juana's minority and the overwhelming interference of France and Castile fuelled the civil war that had been raging in the kingdom for half a century. The fact is that in 1501, when political confrontation and social instability intensified, Brocar left Navarre and settled nearby, in Logroño, but in the social and political calm offered by Castile.

From this point onwards his rise will be dazzling: in the capital of La Rioja he will enter contact with Nebrija, of whom he will edit some twenty titles between 1502 and 1517. project In 1511 he left the Logroño workshop in the hands of his sons and, recommended by the illustrious humanist, he moved to Alcalá de Henares at the invitation of the powerful Cardinal Cisneros, who commissioned him with an ambitious, complex and costly project: the six-volume printing of the Polyglot Bible with texts in Aramaic, Hebrew, Greek and Latin. After bringing it to fruition, Arnao Guillén de Brocar, the printer who had made a name for himself in Pamplona, became the leading printer in Spain and ran a prosperous business with branches in Logroño, Valladolid, Toledo and Burgos, in addition to Alcalá de Henares, where he had his headquarters. He was assisted by his sons and son-in-law, Miguel de Eguía from Estella, who, after his death in 1523, continued the prosperity of the business. Incidentally, Pedro Zalduendo, who probably, like Eguía, was also from Navarre, worked in the Alcalá workshop.

The Missale Tirasonensis (1500)

Having described the context of the printer and his environment, it is now time to analyse the two books with musical notation printed in Pamplona by Brocar. It has already been pointed out that these are missals, i.e. books on the liturgy of the Eucharist as it was celebrated in the different dioceses, where there were considerable variations until the unification decreed at the Council of Trent, which materialised in the Roman Missal published in 1570. But until this date the peculiarities were notable and, consequently, each diocese used its own missal, the distribution of which in the respective parishes and churches was favoured by the printing press.

The demand for this subject of books explains why Brocar, during his time in Pamplona, printed missals for the dioceses of Lescar and Lugo(ca. 1496), Mondoñedo(ca. 1497) and the aforementioned ones for Tarazona (1500) and Pamplona (ca. 1501). Of all of them, only the copies of the last two dioceses mentioned are known, while the rest are known from documentary sources.

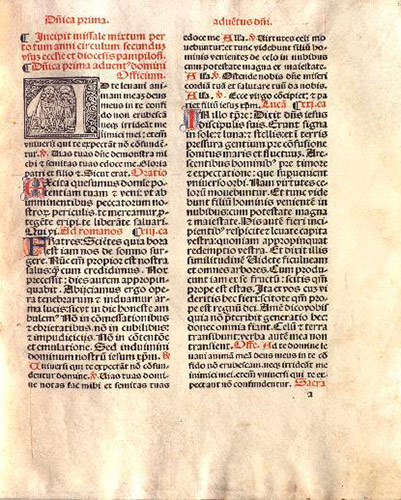

accredited specialization The Missale Tirasonensis is a Issue in folio format, composed of four bifolio notebooks -quaternos-signed but unnumbered, with a total of 338 sheets, equivalent to 656 pages (hereinafter, for ease of enquiry, we will use the pagination of the digital version of the Provincial Council of Bizkaia, which can be downloaded from Liburuklik).

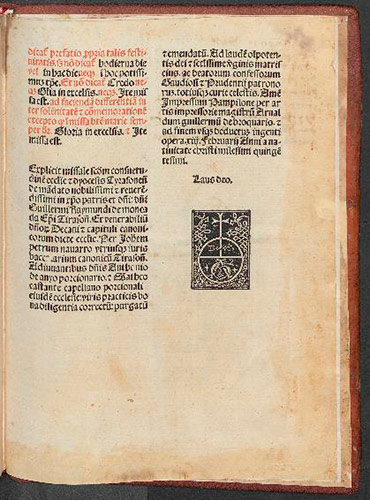

As in most incunabula, it has no title page and, like medieval codices, the Explicit (colophon), located on the last folio (p. 656), gives information on degree scroll, author, printer, place and date and other details. Here it mentions the degree scroll -Missalesecundum consuetudine ecclesie et dyocesis Tirasonensis-, the name of the printer -ArnaldumGuillermum de Brocario-, and the date on which the printing was completed: 13 February 1500. It is also reported that the edition was commissioned by the bishop of the diocese of Tarazona, Guillermo Raimundo de Moncada, a particularly active prelate to whom we owe the construction of the Mudejar cloister of the cathedral to replace the one destroyed in the War of the Two Peters (1356-1369). The prelate's sponsorship is proclaimed at the beginning of the book with a full-page woodcut of his episcopal coat of arms, framed by four tightly set pieces with a continuous vegetal border in which various animals are entangled (p. 2). This is the only illustration that adorns the Missal and which, it should be stressed, is intended to celebrate the figure of its promoter, mission statement .

The Explicit also mentions those responsible for the laborious tasks of correcting and revising the proofs; they are the dean of the cathedral chapter, the high school program Juan Pedro Navarro, the "proporcionario" Antonio de Anyo and the chaplain Mateo Castante. The work is offered in praise of God Almighty, the Blessed Virgin, the blessed Baudilio and Prudencio and the whole heavenly court. The paragraph closes with Brocar's printer's mark, which, with minor variations, is repeated in the works produced in Navarre.

Missale Tirasonensis (p. 656). Explicit and Brocar's printer's mark.

(Biblioteca Foral de Bizkaia. Service of copy center).

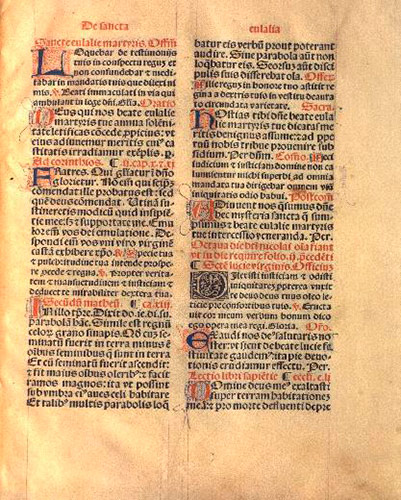

The Issue is printed on strong paper, with gothic characters -predominant in Hispanic printing of the time-, and uses ligatures and abbreviations following the internship of manuscript books. The typography is of high quality and there are four different types or sizes.

The text is divided into two columns of 37 lines, has wide margins and is printed in two inks, black and red, just like the handwritten works. This typographic resource was particularly necessary in missals in order to differentiate the sacred texts and prayers - in black - from the rubrics, the indications addressed to the priest on the ritual to be followed - in red -; in this way the two levels of reading were distinguished.

The copy studied here is kept in the Library Services of the Provincial Council of Bizkaia; it belonged to Enrique Aubá Meseguer (1882-1943), a pharmacist and scholar from Zaragoza, and was donated by his heir to this institution. Other copies, although more incomplete, are preserved in the libraries of the Collegiate Church of Calahorra and the Cathedral of Tarazona.

Ornate initials

If parchment was expensive in the codices, now, with the printing press, paper is also expensive and, for this reason, its employment is rushed to accommodate the greatest possible amount of text; consequently, a tight typesetting is used, with small type and narrow line spacing in order to make the best possible use of space. In order to differentiate the sections of the Missal Tirasonensis, in addition to the inks, initial or capitular letters of different sizes are used, as in the codices, depending on the importance of the passage they introduce.

On this occasion four types of lettering are used. The most prominent are woodcut capitals, printed in black, of large format (they occupy seven lines of text) and Gothic inspiration. They represent the Nativity (for example, on p. 39), the Ascension (p. 241) and Pentecost (p. 252); others reproduce the Trinity (p. 262), the Virgin and Child depicted half-length (p. 508), two decapitated figures holding their heads in their hands, possibly representing the motif of the saintly cephalophores (p. 19). 19), although Martín Abad suggests that they are executioners; and finally, a friar with tonsure (p. 45), which Martín Abad considers to be Saint Stephen, despite the fact that the engraving does not show the martyr's stones as befits the iconography of this saint. The initials with Gospel scenes and those of the Trinity and Mary with Child are used to open the respective feasts, while that of the supposed friar is used for different motifs: the Epiphany, Corpus Christi or the feast of St Stephen. It is worth noting that this chapter - that of the friar - was used by Brocar in the Trojan Chronicle, printed around the same time as this Missal.

Missale Tirasonensis ( pp. 240-241). Capitular with the representation of the Ascension used in the liturgy of this feast (Biblioteca Foral de Bizkaia. Servicio de copy center).

The depiction of a priest kneeling before the altar (p. 350) belongs to the second level of initials, which occupies five lines, and is used to open the section of the Offertory. It has a design and invoice similar to the seven-line initials and, like them, is printed in black. It should be pointed out that this is the only five-line capitular.

The third level - occupying three lines - corresponds to an alphabet with the letters, the framework and the vegetal ornamentation in white standing out against a black background (p. 32). It is used for the beginning of sections or paragraphs. In terms of size and function, it would be equivalent to the Lombard initials, which are ornamented in calligraphy in the codices.

The initials on the fourth level are the height of two lines of text, have only the lettering, without framework or ornamentation, and are printed in red.

Musical notation

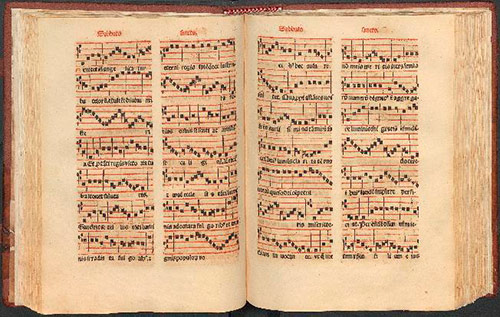

The sung parts of the Missale Tirasonensis concentrate on the liturgy of Holy Week, specifically on Passion Saturday (pp. 144-147), Palm Sunday (pp. 150-152) and Holy Saturday (pp. 191-206), although it also includes the chants of the Gloria and Credo (pp. 335-349) as well as the Ite misa est ( pp. 357-361). The presence of music can be considered marginal, since of the 656 pages it contains only 45 pages of music - less than seven percent.

Like the main text, the musical notation is arranged in two columns, with seven staves in each column printed in red. It should be noted that the employment of the staff is an innovative feature, given that the tetragram was generally used at this time. As far as the musical signs are concerned, average has 21 characters per staff, which are printed in black like the sung lyrics.

The compositions correspond to figured chant or organ chant, which is made up of notes of different lengths - mensural musical notation - indicated by four figures: longo, a black square with a vertical stem; breve, a black square; semibreve, a black rhombus; and mínima, a black rhombus with a stem. The compass is binary and is delimited by the corresponding dividing lines. It should be noted that the Ite misa est has the particularity of being composed for eight tones, in the Gregorian manner, with which special solemnity was given to the end of the mass.

Missale Tirasonensis ( pp. 197-198). Liturgy of Holy Saturday with square notation on pentagram (Biblioteca Foral de Bizkaia. Service of copy center).

Clearly, the typesetting of musical pieces was more difficult than that of ordinary texts: it required characters whose graphic diversity was much greater than alphabets, the work of skilled typesetters and "double printing": usually first the musical guideline was printed in red and then the general text and musical signs were printed in black.

In the early days, woodcut plates were used, as well as zinc or tin plates that reproduced a page with musical notation, in such a way that their printing was similar to that of engravings; but this technique - "block printing"- was only viable for small works due to the high cost of opening the plates.

The musical lines were also printed out, the pautado, to later add the notes by hand as the amanuenses had been doing in the codices.

Subsequently, "double printing" was used, as Brocar did in the Missale Tirasonensis, in which he printed in black the main text, the musical notes and the sung lyrics, and then printed in red the headings of the folios, the rubrics, the small initials and the musical guideline . All this required, it is worth repeating, great skill in the "register", the adjustment of the page.

Around the same time as the Missale Tirasonensis, from 1501 onwards, the Venice printer Ottaviano Petrucci de Fossombrone, who specialised in musical editions, introduced the "triple printing": the first one for the page layout, the second one for the musical notes and the third one for the text, the ornamented initials and the issue page. With this procedure he obtained the most important editions of his time.

This process was simplified in 1527 when the Parisian printer Pierre Attaingnant began to use musical characters that incorporated the corresponding line of the page layout, making it possible to print in one go, with a single stroke of the press. issue From this time onwards, the printing of music books became less laborious, although during the printing era guide it remained confined to a small number of European workshops, among which the Venetians were at the forefront.

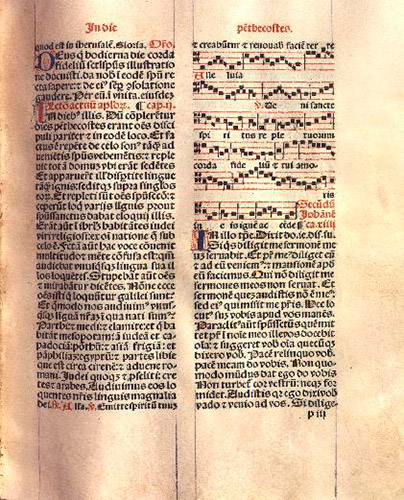

The Missale Pampilonensis (ca. 1501)

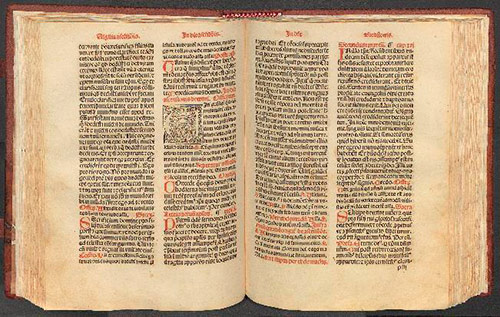

Following the Missal of the diocese of Tarazona, around 1501, Brocar printed the Pamplona Missal. His degree scroll appears after the six folios that describe the ecclesiastical calendar month by month; at this point we read: Incipit Missale mixtum per totum anni circulum secundum usum ecclesie et diocesis Pampilonensis. Neither the first nor the last leaf has survived, so it is not known whether it had a colophon; in any case, the place of printing, the printer and the date are unknown, although the formal characteristics undoubtedly point to Arnao Guillén de Brocar.

Missale Pampilonensis (p. 17). Incipit with the degree scroll (Library Services Navarra Digital).

Thus, the similarities with the Tarazona Missal are as eloquent as they are constant: the format is also in folio and is made up of quaternos signaturizados, but without numbering. It has 316 leaves, equivalent to 632 pages (for ease of reference enquiry, the pagination of the Library Services Navarra Digital version is indicated hereafter); the lettering is also gothic, clean and likewise in four sizes. employment The page layout, as in the Tarazona copy, is in two columns with 37 lines, printed in two inks, with black and red for the same purposes; but on this occasion, unlike the Tarazona Missal and following the usual guideline among printers of the time, the red ink was printed first and then the black.

The file Library Services of the Chapter of Pamplona Cathedral conserves two copies, both incomplete; one printed on vellum, which would belong to a print run as luxurious as it was short, and the other on paper corresponding to the ordinary edition.

The engravings

As for the illustrations, while the Tarazona edition only sample shows the coat of arms of the bishop who promoted the work, on this occasion, since there is no reference letter at publisher, full-page religious engravings are used. The first reproduces the Crucifixion, with Mary and St John standing flanking Jesus in a soberly depicted landscape (p. 340). It is well executed, with a sober and balanced composition that is given a certain dynamism by the cloth of purity floating in the wind. At the bottom are the initials of the author: "I.D.", which could be identified with a Flemish engraver whose works are used in workshops in France and Spain. It has a vegetal border made up of four poorly assembled pieces in the lower left corner. This engraving is used again by Brocar in the Constitutions provincie Cesaraugustane dated 1501.

The second woodcut depicts the Last Judgement, with Jesus in Majesty over the rainbow, flanked by two angels calling the dead out of their tombs with their trumpets (p. 341). From the trumpets sprout phylacteries with the legend: Surgite mortui. Venite ad Iudicium; under the Saviour, kneeling on clouds torn by lightning, Mary and Saint John the Baptist appear. It is an archaic, stereotyped composition, although the execution is correct. The initials "I.D." are repeated at the bottom. The framework of the illustration, made up of four pieces, is the same one that adorns the coat of arms of the bishop of Tarazona.

The engravings have been printed on separate sheets and have been inserted in the middle of Issue, facing each other, without any text. They are not related to the subjects dealt with in the adjacent pages and their presence would only be a typographic display, intended to enhance the quality of the publication.

Ornamental initials

With regard to the employment of initials, once again there are coincidences with the Tarazona Missal . The seven-line capitulars, already described, are again used, reproducing the Nativity (p. 36), the Ascension (p. 225), Pentecost (p. 236), the Trinity (p. 248), the Virgin and Child (p. 551), the cephalophora saints (p. 17) and the cephalophora saints (p. 552). 551), the saintly cephalophores (p. 17) and the full-length friar (p. 250); the only novelty is the use of a capitular with the topic of the Resurrection (p. 199) which is not found in the Tarazona copy. Also repeated is the five-line initial with the topic of the priest officiating at mass (p. 343), as well as the three-line initial with vegetal decoration on a black background.

To emphasise the extraordinary quality of the copy of the Missale Pampilonensis printed on vellum, following model of medieval codices, the three- and two-line capitulars printed in red were reworked: in some cases the initials printed in red were respected and decorated with Gothic-inspired blue strokes; in others, the red initials were carefully scraped and redrawn in blue ink, making the red printing ink disappear, and decorated with red strokes. The similarly sized capitals printed in black with ornate backgrounds were not retouched, as it was not possible to repaint them and decorate them with hand-drawn ornamental strokes. Finally, in order to reinforce the verisimilitude with the medieval codices, the writing box of the columns of the text was marked with vertical strokes in red ink.

Missale Pampilonensis (p. 627). Handwritten initials -two and three lines- and printed -three lines- on the vellum copy.

and printed -three lines- on the copy on vellum

(Library Services Navarra Digital).

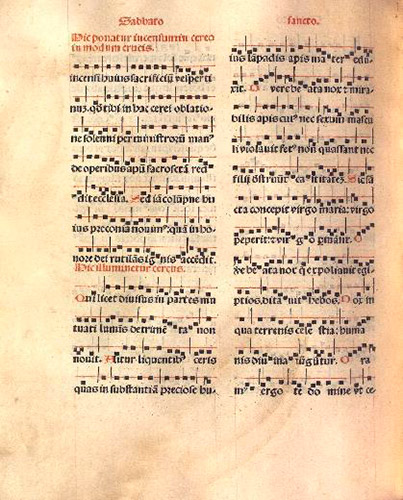

Musical notation

The compositions correspond to plainchant or Gregorian chant and, consequently, the notes have the same value, which is indicated by square crotchet notation placed on a single musical guideline -internship archaic dating back to the 13th century -; the exception is found on page 237, where the tetragram, widely used in publications of this period, is employed.

Missale Pampilonensis (p. 184). Gregorian notation with a guideline for the Holy Saturday liturgy (Library Services Navarra Digital).

Each column contains twelve pautados, five more than the Tarazona Missal, and this is due to the fact that only one line is used for the pautado and, for this reason, the space available is greater; as far as the issue of types per line of music is concerned, it is similar to that of Tarazona.

The musical compositions correspond to the Fourth Fair (pp. 69-70), Sixth Fair (pp. 174-185), Pentecost (p. 237) and the chants of the Gloria (pp. 332-338), and the Pater Noster (pp. 350-352); in total they add up to 33 pages, compared to 45 in the Tarazona Missal.

Missale Pampilonensis (p. 237). Musical notation on tetragram

(Library Services Navarra Digital).

Three and a half centuries of silence, with one exception

The first printer in Navarre was fully capable of publishing books with musical notation, and to do so with quality as early as the missals of the dioceses of Tarazona (1500) and Pamplona (ca. 1501).

It took more than a century for a Navarrese printer to publish another music book: it happened in 1614, when the workshop of Carlos Labayen printed the Liber Magnificarum, a choir book with more than two hundred pages, practically all with musical notation, which included the polyphonic compositions of the master of the music chapel of Pamplona Cathedral, Miguel Navarro. The unusual thing is that after this publication, for almost two and a half centuries the Navarrese printers did not publish - probably could not - another work with musical notation. Finally, in 1848, the Pamplona workshop of José Imaz y Gadea printed the Nuevo método completo teórico-práctico de canto-llano y figurado, by the cathedral "psalmist" Fermín Ruiz de Galarreta, in which, as in Brocar's missals, musical pieces were interspersed. As the author explains in the Prologue, the musical examples were printed with xylographic blocks that he himself had opened, following an archaic procedure more rudimentary than the employee by Arnao Guillén de Brocar.

Consequently, after Brocar's work, with the exception of the unique edition of the Liber Magnificarum, Navarrese printers did not print works with musical notation, and this was because their level of training, both human and technical, was modest, as was that of most of the workshops of the time. issue The exception was to be found in a small number of workshops located in the large production centres of Madrid, Barcelona, Seville, Salamanca and Zaragoza.

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

Missale mixtum secundum usum ecclesie et diocesis Tirasonensis [Missale Tirasonensis]. Pamplona, Arnao Guillén de Brocar, 1500. Copy from the Library Services of the Diputación Foral de Bizkaia. available in Liburuklik (accessed 19-XI-2019).

Missale mixtum secundum usum ecclesie et dioecesis Pampilonensis [Missale Pampilonensis]. Pamplona, Arnao Guillén de Brocar, ca. 1501. Pamplona Cathedral copy. available at Library Services Navarra Digital (accessed 19-XI-2019).

RUIZ DE GALARRETA, F. Nuevo método completo teórico-práctico de canto-llano y figurado. Pamplona, José Imaz y Gadea, 1848. available at Library Services Navarra Digital (accessed 18-XI-2019).

GOSÁLVEZ LARA, C. J., La edición musical española hasta 1936. guide para la datación de partituras, Madrid, association Española de Documentación Musical, 1995.

HERNÁNDEZ ASCUNCE, L., "El misal incunable de Pamplona", La Avalancha, 1934-VII-24, pp. 213-214.

ITÚRBIDE DÍAZ, J., Los libros de un Reino: Historia de la edición en Navarra (1490-1841), Pamplona, Gobierno de Navarra, 2015.

MARTÍN ABAD, J., Cum figuris. Texto e imagen en los incunables españoles. Catalog bibliográfico y descriptivo, Madrid, Arco Libros, 2018.

MELE, G., "Los orígenes de la imprenta musical", Goldberg, 2004, n. 31, pp. 38-45.

MOSQUERA ARMENDÁRIZ, J. A., Compendio de la vida y obra de A. G. de Brocar, Pamplona, El Autor, 1989.

ODRIOZOLA, A., Catalog de libros litúrgicos, españoles y portugueses, impresos en los siglos XV y XVI, Museo de Pontevedra, 1966.